All illustrations are from the author's collection. You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the author and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images for larger pictures.]

t was Rembrandt in the seventeenth century who first freed etching from its mainly reproductive purpose of spreading the knowledge of paintings by copying them onto copper plates for a wide distribution. Rembrandt, using the copper plate like a page from a sketch book, put down freely from life the details of the scene in front of him, or needled freely on the grounded metal plate (with a metal scriber) transcriptions of sketches made for this purpose from life or imagination. In this way, not depending slavishly upon a painting he was reproducing, Rembrandt gave the immediacy of life to his prints. By and large, this kind of etching did not find subsequent practitioners over the years until the nineteenth century and etching was still used mainly for commercially reproducing existent paintings. Rembrandt's prints had been in his lifetime collected by discerning admirers for the sake of the intrinsic artistic qualities of the medium in itself, not as reminders of other works.

t was Rembrandt in the seventeenth century who first freed etching from its mainly reproductive purpose of spreading the knowledge of paintings by copying them onto copper plates for a wide distribution. Rembrandt, using the copper plate like a page from a sketch book, put down freely from life the details of the scene in front of him, or needled freely on the grounded metal plate (with a metal scriber) transcriptions of sketches made for this purpose from life or imagination. In this way, not depending slavishly upon a painting he was reproducing, Rembrandt gave the immediacy of life to his prints. By and large, this kind of etching did not find subsequent practitioners over the years until the nineteenth century and etching was still used mainly for commercially reproducing existent paintings. Rembrandt's prints had been in his lifetime collected by discerning admirers for the sake of the intrinsic artistic qualities of the medium in itself, not as reminders of other works.

The formation of the Sociétié des Aquafortistes of 1862 (aqua fortis: strong water, meaning acid), the Sociétié des Peintres-Graveurs of 1889 and the Society of Painter-Etchers, 1880 (a Painter-Etcher meaning an artist who etches to produce an original work representing the artist's inspiration in that particular medium as opposed to him making a reproduction of some other artist's picture commercially for the market) came about from a new fascination for the whole process of the hand-produced print.

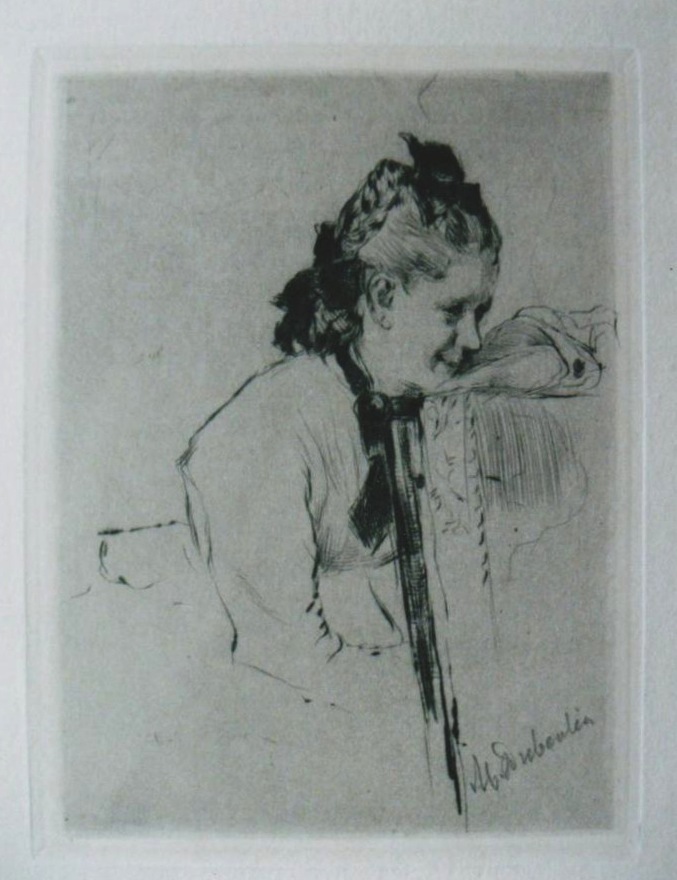

Femme au Métier, Marcellin Desboutin (1823-1902), 6½ x 4¾ in. Desboutin was a prominent French etcher of the late nineteenth century, whose work typifies the approach of the Sociétié des Peintres-Graveurs.

There was a great interest in, and enthusiasm for, all stages of the making of an etching (as with Rembrandt's approach): the needling through an acid-resistant ground spread on the copper plate, the selection of the paper and the actual printing. This is not to say that at times the artists did not use specialist printers, such as Delâtre in France (also used by some English artists) but such printers were dedicated to working in the way the artist wanted and had already demonstrated to them.

The intention of the exhibitions of these societies was that they should display original prints, not reproductive etchings after successful paintings that had been exhibited in the Paris Salon or the Royal Academy. However, members did at times make such plates, for no doubt financial reasons, as did Rembrandt himself with plates after his own paintings such as The Deposition. But it was Rembrandt's immediate and direct country views that inspired the etcher Seymour Haden in his founding of the Society of Painter-Etchers in London.

The Inn, Purfleet, Sir Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910), 10 x 7 in. Haden, as mentioned above, was the founder of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers.

Haden had many friends among the French etchers and persuaded them also to join his new group – Alphonse Legros, Félix Buhot, James Tissot, etc, so there was an international feel to the Society from the first. James MacNeill Whistler himself, having quarrelled with Haden (his brother-in-law) was however never a member, despite his directly needled early Thames Set being typical of the new free approach.

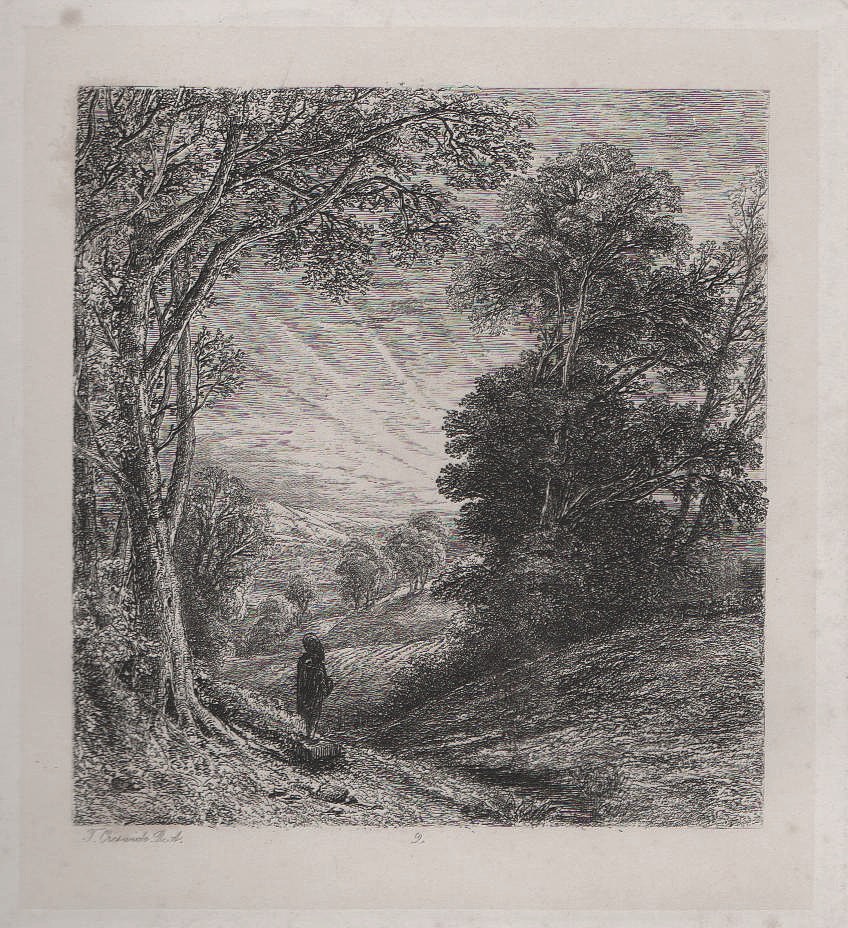

In England, the Old Etching Club had been inaugurated in 1838 to exhibit original prints, and a breakaway of younger members formed the Junior Etching Club in 1857. In these clubs the concept of original etchings was not exactly in the Rembrandt manner of immediate sketching from life, leaving a great deal of the plate free from lines and with a sense of the open air. Members of the earlier Etching Clubs, such as John Everett Millais, Samuel Palmer, Hook, Thomas Creswick and William Holman Hunt, made elaborately cross-hatched finished plates rather than sketch effects.

Left: Evening, Thomas Creswick (1811-69), 5 x 4½ in. Creswick was a member of the Etching Club. Right: Life Room, Royal Academy, by Charles West Cope (1811-90), 6 x 9¾ in. Cope was also a member of the Etching Club.

Seymour Haden, because his style was freely needled direct work with the character of a sketch, made on the spot, rather than elaborate worked up subjects, resigned from the Junior Etching Club, and formed the 1880 Society of Painter-Etchers. The direct style of Hayden and Whistler tended to typify the (later Royal) Society of Painter-Etcher's approach over the subsequent years. Of course, working on the site inevitably reversed the image in the subsequent print, but Whistler reckoned that an etching was an artistic production, not a topographical souvenir.

Little Dordrecht, by Whistler (1834-1903), 3¾ x 5¼ in.

Today no etcher makes reproductions of paintings as there are far more sophisticated printing methods available to the market, but the hand-made etching, representing all kinds of imaginative subjects and techniques, continues to typify the now re-named Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers – the title altered in the late twentieth century to admit of various other forms of original printmaking.

Related Material

Further Reading

Guichard, Kenneth M. British Etchers 1850-1940. London: Robin Garton, 1977.

Harvey-Lee, Elizabeth (scholar and print-dealer). Original Prints: 15th-21st Centuries. Web. 12 January 2015.

Hopkinson, Martin J., with a List of the Diploma Collection by Clare Tilbury. No Day without a Line: The History of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers, 1880-1999. Ashmolean Museum, 1999.

Lumsden, E. S. The Art of Etching (1924). New York: Dover, 1962 (a republication).

Created 18 January 2015