Foolish Speech to naught may fly

But awful book words know not how to die.

—James Smetham, nineteenth century artist and Ruskin friend; from an obituary in The Methodist Times, 1 September 1921

Now that we have learned that Ruskin was not the erotic degenerate some have claimed he was, other issues require our attention. As instances: we do not have, as yet, an adequate explanation of why it happened that our subject, all but universally regarded as one of the intellectual giants of the nineteenth century, became, as the following century drew to its close, the target of a bevy of accusations alleging that he was sexually repugnant. Nor have we fully explained why it happened that his once vigorously applauded work, all of which centers around arguments intended to help us understand how we can live together more humanely and joyously, is, today, all but ignored; nor, in the same vein, have we discussed in any detail one of the principal charges against him, the contention that his work was hypocritical, a claim which has proved as difficult to dislodge as those conjecturing his erotic perversity. Nor do we adequately understand why it happened that, once the speculation that he was sexual blamable moved from the academic into the public arena, it assumed adamantine status, became a conviction inviolable no matter the arguments and evidence offered either in counter to or in mitigation of the accusation. Nor—reflecting on the analysis completed in the last chapter—now that we know that Ruskin’s sexuality was not perverse, do we have any clear idea of what it actually was or how it came to be that the considered choices he made about how he would express and regulate the erotic aspects of life unintentionally became part of the bait attracting those who, like a pack of wolves in the dark eagerly eyeing their prey, stood at the ready to rend him and his reputation as soon as the opportunity presented itself.

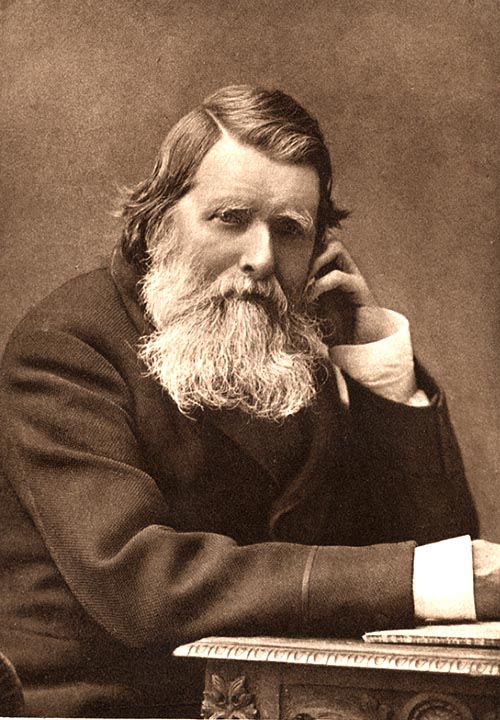

Two photographs of Ruskin, the first by Lewis Carroll and the second by an unknown photographer.

It is to these issues that we now turn, the intent being that, once they have been examined, the last pieces of the puzzle required to explain the mystery of Ruskin’s sexuality and the strange and untoward reactions which have attended it will fall into place.

A Grave Misperception, Two Conspiracies: Their Consequences

I return to the Saturday classes of 1887, the gatherings where Ruskin’s erratic behavior with his (mostly) girl guests so upset his caretaker cousin, Joan Severn, that, regarding his actions as “unbecoming,” she put a stop to the gatherings, an edict which opened a serious rift between the cousins and set in motion the catastrophe of Ruskin’s next two years, a time during which he lived, first, alone and despondent on England’s south coast, and then, in desolation as he traversed his “Old Road” from Calais to Venice for the last time, a sojourn which, by its end, would eventuate in his complete mental collapse (Spates, “Dark Night”: 18-30).

Two photographs of the older Ruskin from the Library Edition.

New evidence presented in our earlier discussion of the Saturday classes afforded alternative explanations for the behaviors that worried Joan (and Hilton; cf. Later Years: 537-8). These suggested that Ruskin was not behaving in a manner indicating an unhealthy interest in girls, but showed that he acted as he did partly because he had not yet recovered from his psychotic episode of the year before and partly because he was genuinely delighted by the children’s exuberant behavior. Other evidence demonstrated that his actions at this event were strikingly atypical of his behavior vis-à-vis young females generally, during which encounters, all of those who recalled them later, remembered him as a gentle, consummate gentleman.

Left: Ruskin and Joan Severn in the 1890s. Right: Charles Eliot Norton, Harvard’s Professor of Art.

Which raises a critical possibility: that the stressed, always anxious, intensely reputation-conscious Joan overreacted to what she saw happening at the Saturday gatherings and, dismissing out of hand her cousin’s contention that his behavior was perfectly innocent, decided that, in this matter of girls, he was unwell. In short, although Joan can hardly be faulted for not having to hand the indices which today’s psychiatric community uses to determine the presence of a serious sexual disturbance, she blundered and misdiagnosed Ruskin, imputing to his behavior a disturbing subtext it did not contain, and, in doing so, made an egregious error, an error which, as it played out and other misinterpretations and overreactions were added to it, became the recipe for the grim interpretations of his sexuality with which we still contend.

I am not saying that the Saturday classes were the sole stimulus of the misperception. Far from it. By 1887, for almost two decades (as we have seen) in some of the multitudes of letters he sent and not infrequently in conversation, Joan had heard of Ruskin’s interest in young females. Her unease about the issue, coupled with worries over his never-dissipating depression and often erratic behavior, grew by accretion. In the wake of which, at some point (the exact moment we do not know), she decided, almost surely in consultation with others whom she trusted, that she must—for his health and reputation’s sake, for her and her family’s reputation’s sake!—do all she could to control the situation, the termination of the classes being an instance.

Her mind made up on the matter, she pressed on. A considerable body of evidence exists informing us that Joan communicated her interpretation to others, some of whom, having witnessed some of the behaviors which upset her, concurred with her judgment, the hardly surprising result, given Ruskin’s fame and the usual fate of spicy gossip, being that, over time, her view that her cousin was sexually abnormal became a fairly widespread open secret, first in Coniston, then in the London literary and art circles, and finally throughout the UK. In this sub-rosa form it simmered until the subject of the unpleasant rumors died on 8 January 1900, after which a process which would culminate in an extremely forbidding portrait of Ruskin began.

Throughout his days, always an advocate of speaking truth, even if that truth was warted, Ruskin asserted that, if his story were to be told, it should be told full, without excision or censor (Bradley and Ousby: 8). Beyond the sacrosanct principle of veracity, it was not, as he saw it, a problematic stance to take, for, in the life that would be revealed, whatever his difficulties may have been, there was nothing which would require need for erasure. Earlier we read how he always said that anyone was always free to commit anything he had ever said or wrote to print. Even after he had returned from his catastrophic last trip to the Continent of 1888, he wrote, on May 29th, to a friend, in reaction to some critical remarks he had penned regarding a newspaper article written about The Guild of St. George, “You may print this beginning [of my rejoinder] when and wherever you like; as anybody else may, whatever I write, at any time—or say—if only they don’t leave out the bits they don’t like!” (Wise, 97).

Unfortunately, this commitment to telling all was not shared by the three intimates Ruskin had selected as executors of his Literary Estate: Joan, his close friend of decades, Harvard Professor of History and Art, Charles Eliot Norton, and his former Oxford student and devotee, Alexander Wedderburn. Ignoring their subject’s instruction in the letter just cited—which was printed in the journal, Ruskiniana in 1890—immediately after Ruskin’s passing on 20 January 1900, a series of discussions and decisions began which, by the time they terminated a dozen years later, would omit literally thousands of bits the triumvirate didn’t like.

Directly after receiving the news that his friend had departed, Norton wrote Joan telling her that, to initiate the process of managing Ruskin’s literary heritage, as well as to see and comfort her, he would get to Brantwood as soon as possible. From the first, however, he was determined that all references that might prove embarrassing to Ruskin’s reputation would never find ink. If “it depends on me,” he wrote to the English literary critic Leslie Stephen at the time, “there would be no further word of Ruskin or about him given to the public. Enough is known… I have never known a life less wisely controlled or less helped by the wisdom of others than his. The whole prospect of it is pathetic: waste, confusion, ruin of one of the most gifted and sweetest natures the world ever knew...” (Bradley and Ousby: 511) Joan, considerably out of her depth regarding what to do with her cousin’s massive unpublished legacy, was thrilled that Professor Norton would take the complex reins: There “is no one with whom either the beloved Coz or I could trust with such perfect confidence as yourself to decide what is best about all his private papers…” she told him on 24 January 1900 in response to his offer to cross the Atlantic.1

Two watercolors by Arthur Severn. Left: Ruskin’s Bedroom at Brantwood. Right: An Unidentified Italian Bay, which hung in Ruskin’s bedroom. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

As it happened, Norton did not arrive until June 1901. Immediately, he made the feelings he had shared with Stephen known. Always deferential to authority, Joan agreed with the plan to censor. They made a pact, deciding that nothing, or as little as possible given what was already in the public realm, would be preserved from the vast assembly of letters at Brantwood which dealt with Ruskin’s abiding and corrosive struggle with his father over the direction his life should take, with his struggles with mental illness and depression, with his discovery—while cataloging Turner’s “Gift to the Nation”( over 20,000 drawings and paintings)—of what he regarded as the appalling truth of his idol’s sexual life, with what both regarded as his obsession with Rose La Touche, or (of course) anything which pointed to his intense interest in girls and young women.2

Left: Brantwood in early spring.. This photograph clearly shows the seven windows that Ruskin had built into the dining room to symbolize the Seven Lamps of Architecture. Right: The Gardens at Brantwood looking toward Lake Coniston. This photograph was taken very near the spot were Joan Severn and C. E. Norton burned the Ruskin and Rose correspondence. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

This understanding in mind, on a lovely Lake District day in early Spring, they repaired to the garden behind Brantwood’s main house and, there, burnt the rosewood box containing what they thought were all the letters Ruskin had exchanged with Rose (LE 35.lxxvi).3 Departing not long after, Norton secured a promise from Joan that she would do all she could to gather collections of Ruskin’s letters still in the hands of his most intimate correspondents and, after isolating those she thought incriminating in any of the above respects, would attempt to convince the owners to let her destroy the unsettling ones. For his part, Norton would return to America, revisit his own huge collection of Ruskin letters, and consign to the flames any which he deemed might raise eyebrows (Bradley and Ousby: 1-17).

Brantwood. Alexander Macdonald. 1880. Watercolor. Reproduced by the kind permission of the Ruskin Museum, Coniston. Click on image to enlarge it.

As this agreement was being put into action, another collusion involving Joan, one also intended to keep Ruskin’s reputation free of disagreeable suspicion, was emerging. When he died, despite the fact that there was broad awareness of his mental struggles and some soto voce murmurs to the effect that there might have been something unsavory about his sexuality, Ruskin was still one of the most revered figures of the era. To capitalize on that status, especially given that the entirety of his output had never been collected, it occurred to Wedderburn and Severn that, should a multi-volume compilation appear, to be sold by subscription, it might serve a dual purpose: become a enduring tribute to his genius and, into the bargain, make them not a small amount of money. And in this way The Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin was born.4

Each volume (there would eventually be 39) would be introduced by a biographic essay which would frame its contents. To supply the base materials for the introductions, the immense cache of letters at Brantwood would be posted to Wedderburn in London where he would oversee the making of typescript versions, after doing which he would return the originals. In addition, Wedderburn would solicit the letter collections of Ruskin’s other friends and noteworthy correspondents, and have these typed before returning them to their owners. Important letters pertaining to Ruskin’s life not used in the introductions were reserved for two later letter volumes (LE 36, 37) intended as a representative sample of his correspondence over the course of his life. After W. G. Collingwood, another Ruskin devotee—who disdained the project as a money-making scheme of which Ruskin would disapprove—refused an offer to be co-editor, E. T. Cook, who had published a book applauding Ruskin’s genius in 1891, was brought in.

Left: Alexander Wedderburn. Ralph Peacock. 1901. Oil on canvas. Reproduced by the kind permission of Robin Wedderburn. Right: E. T. Cook. Courtesy of ther National Portrait Gallery, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

While there can be little doubt that the Victorian belief that one should never wash one’s dirty linen in public played a role [the burning or censure of what were considered incriminating letters was still in vogue—as demonstrated in the volume that presented a very carefully culled version of the Ruskin-Alexander correspondence (Swett)], there is no doubt that it was painfully obvious to Joan and Wedderburn that, if the Library Edition was to garner the profits they desired, it would hardly be likely to do so if its subject’s weaknesses and complex erotic life were accorded much space. And so they resolved that the rehearsal of Ruskin’s story which would be presented in each volume would necessitate careful composition. As preparation, they would have to cull from the vast array of holographic material available any that pointed in any significant way to his “sensitive issues.” Once this had been done, Cook, who had been given the task of writing the introductions, would be given the expurgated remainder, and then, under Wedderburn’s watchful eye, compose the story they wished told. Since only the editors had access to the original documents which would be used to create the introductions and later letter volumes, no one reading the final products would have any idea what had been either edited for effect or left out entirely.

A plan for the purging was made. First Joan, at Brantwood, would make her systematic way through the letters there, blacking out problematic passages or destroying entirely any letters she thought too revealing. This done, she would post “cleansed” packets of missives to Wedderburn, who, once the letters had been typed, would, after reading all, choose those that told the story as he wished it told, pass these on to Cook, making it clear via a series of pencil marks that certain remaining portions could not be used. Among the most revealing of the letter collections were the many hundreds Ruskin had exchanged with his parents. On his death, Wedderburn willed the typescripts of these to Yale, surely because the university had purchased the entirety of the family holographs from Arthur Severn in 1930 (Spates, “Legacy”). Readers of these typescripts (Beinecke Library, MS Shelves Vault Ruskin), frequently encounter his censorious pencil marks.

Margaret Ruskin by Sir James Northcote, RA. Right: John James Ruskin by Sir Henry Raeburn, RA. Reproduced from Library Edition. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

And so it happened that Joan became the center of not one but two conspiracies, both devoted to managing what immediate and future audiences would learn of Ruskin’s life. The following instances give a sense of how complex the bowdlerizing process became.

During Norton’s visit, Joan had informed him that the hundreds of letters Ruskin sent to Lucia and Francesca Alexander in the 1880s would be virtually overflowing with concerning content. In no uncertain terms, Norton told her that she must get them, the hope being that, later, the Alexanders would let her destroy any revelatory material. Joan, who, over the years, had grown close to the Alexanders in correspondences of her own, wrote Francesca, who immediately refused the request. Vexed, after being told by letter of the refusal, Norton insisted that Joan try again. She did and was again rebuffed. When a third request, this one couched as coming from Wedderburn and Cook as editors of The Library Edition, received a third rejection, she backed off. Her Fratello’s letters were, Francesca explained in her letter to Joan, “very private”, the great majority having only to do with his publication of her (Francesca’s) books; “[O]f the rest,” she wrote, “some were written when he was not himself…They are among the most precious things I possess. But I think I would rather see them all in the fire than in the hands of a stranger. Dear Joanie, I trust you will not think me unreasonable. I am certain that, in my place, you would feel as I do. Please make the executors understand this” (Previously unpublished: Houghton Library: bMS 1088). And in this way one of the most important and confessional of Ruskin’s correspondences, every bit as worrisome regarding Ruskin’s “issues” as Joan and Norton imagined, was preserved by means of an Alexander family gift donated, decades later, by Francesca and Maria’s relatives, to The Boston Public Library.

Solicited to help in the process of deciding which letters to purge or cut at Brantwood was a former secretary of Ruskin’s, Sara Anderson. Over the years, Sara and Joan had become dear friends. A letter Sara sent to Joan (then living at Herne Hill, the former Ruskin family home in London) on 7 May 1906 shows the collusion at work: I am sending you, she said, some letters “which are of a more or less controversial character, & [which] I think should either be burnt or sealed up & put by themselves.” Reading these, Joan decided on the former course and so informed Sara. To which news Sara responded in her letter of 12 May: “I am more than thankful that [the] letters were burnt. I have now read all your letters [which you sent to the Di Pa] and [have] burnt all those relating to the terrible Rosie times. All the others are readable by anyone, so that we have a weight off our minds. I have done up Rosie’s own letters to you, sealed them, & put ‘for Joan only’ outside… Do search your mind for anything else that requires looking over, & send it or keep it for me, & don’t let us have scandals turn up after our lamented demises.”6

What happened to the Rose letters Sara left for Joan we don’t know, but there is good reason to think they met the same fate as the rosewood box containing the Ruskin-Rose letters which Joan and Norton had consigned to the flames in 1901, as indicated by a comment in a missive Joan sent Norton on 20 December 1904: “I thought,” she writes there (having just found out, to her consternation, that Norton published letters where Ruskin mentions Rose), that, on the day “when we made the little sacrifice in my beloved Deepie’s [“Di Pa”] little garden here, we agreed to burn all letters bearing on that sad subject--& I have done so--& destroyed many since [which were sent] to myself and others.”7

The exacting censoring process continued throughout the years the Library Edition was being published. As late as 1912, the year the last two volumes appeared, Sara was reassuring a member of the Millais family (which had resolved that the love letters Ruskin sent Effie during their courtship should never see the light8) that she, the Severns, and Wedderburn, were all “as anxious as you are to see that nothing should be left that could ever, by accident, fall into the wrong hands in after years.” (Viljoen, Heritage, 6)

The Three Volumes of Fors in the deluxe version of the Library Edition, which included a matching leather envelope containing a letter by Ruskin. Collection George P. Landow.

The very brilliance and professionalism of the Library Edition was integral to the success of the biographic façade. As a closely-referenced scholarly presentation of a great writer’s works, it has few, if any, equals. From the first page of the first volume to the final page of the thirty-ninth, the editors’ exacting treatment never varies. As required, every sentence, every arcane reference, every newspaper article cited by Ruskin, is exhaustively footnoted and annotated. Although in the end sales of the collection disappointed, the finished product remains one of the greatest tributes to the works of a literary giant ever printed, a series which remains indispensable to any scholar wishing to study Ruskin and his oeuvre in any detail.

But—and exactly as the editors intended—this same professionalism served as a smoke screen. Given that subscribers had been informed that, as the volumes were prepared, the compilers had to hand the holographs of the vast majority of Ruskin’s manuscripts and letters, and given that each volume’s introductions and the two volumes devoted to his letters were written in the same authoritative manner as the commentaries and annotations presenting his books, lectures and unpublished manuscripts, it never occurred to anyone that suppression and carefully calculated excision were afoot.

But like most obfuscations of similar type, eventually the smokescreen began to dissipate. As early as 1956, the Ruskin biographer Helen Viljoen, who had learned of the cover-up in 1929 when she had the opportunity to read thousands of Ruskin’s unpublished letters in holograph at Brantwood before they were dispersed (see below), had warned that the Library Edition’s biographic sections could not be trusted, and that if an accurate biography of Ruskin was ever to be created, it could only happen if the biographer consulted the thousands of original documents which told his story in his own hand (Heritage, 2-3)9. To take but one, albeit critical, example: coming to the one substantive account of Ruskin and Rose’s love for each other in Volume 35 of the Library Edition (lxvi-lxxvi)10, a naïve reader is left with the impression that it was all terribly sad, instead of the much more accurate depiction that would have made it indubitable, and the affair was the signal event in both lives and an unremitting, daily source of angst for Ruskin over the course of the last forty years of his life, twenty-five of which passed after Rose’s death in 1875 (Burd, Rose, “Introduction”); for a second example, a careful review of surviving letters makes it crystal clear how severely Cook and Wedderburn altered the story of Ruskin’s complex and intense relationship with the artist Kate Greenaway so that any suggestion of a possible romance having ever existed between them went unperceived (see later discussion).

In short, the Library Edition is a magnificent tribute forever marred by the conspirators’ decision to fashion a biography of Ruskin designed to intentionally mislead the readers of it.11 While excision of material thought threatening to reputation before publication is hardly a new practice, in this case the choice was extraordinarily damaging. Indeed, after a few decades had passed and, in the wake of Viljoen’s early warning, little by little it became clearer that some kind of systematic beclouding of Ruskin’s “problems”—particularly the sexual ones—had occurred and that readers of the Library Edition had been duped, it needs to be said that this decision to fashion Ruskin’s story into palatable form has to be seen as the watershed event which set in motion the events which would eventually ensure that his reputation would plunge to depths before unimaginable, as later writers, assuming that what had been hidden must surely have been repellent, began to propose just that.

Arthur Severn Reading. Laurence Hilliard. Used by permission of the Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster, Lancaster, UK. Click on image to enlarge it.

There is one more, extraordinary, part of the story, a twist of literary fate nearly incredulous. Joan died in 1924. By the end of the decade, her husband, Arthur, never a great fan of our subject, resolved to sell the thousands of his letters, manuscripts, and diaries remaining at Brantwood to the highest bidders. As it turned out, Ruskin’s cultural significance still widely appreciated, not a few of those higher bidders came from the western side of the Atlantic. The result was that a majority of the letters shedding light on what the co-conspirators had decided were the problem areas of his life sailed over an ocean to new homes in America. In addition to the Morgan and Yale, other major repositories in America of Ruskin’s letters are at Harvard’s Houghton Library (the Severn-Norton correspondence), The Boston Public Library (the Alexander letters), and The Huntington Library (the Susie Beever letters); cf. Spates, “Legacy.”

At all events, the fact that all this biographic material migrated to America meant that anyone doing biographic work on Ruskin in the UK and Europe after the sales ended in 1931 did not have easy access to a large proportion of the material absolutely essential for telling his story accurately. Nor did such researchers have any sense—so successful had been the Library Edition’s intimation that it had told all in need of telling and that truthfully—why the thousands of letters housed on a continent thousands of miles away were vital to consult. As a result, traverses of the waters in the service of a Ruskin biography based on a careful consultation of all the extant holographs simply did not occur.12

And so it has remained. As of this writing, with the exception of Brownell’s revelatory new work on the marriage (discussed in the previous chapter) no Ruskin biographer desirous of telling the whole of Ruskin’s life story has taken the time the time to immerse him or herself in the major stores of letters preserved, in some cases for nearly a century, in North America. The catastrophe of this bifurcation of material has been tragic, because, as we have seen, those who wrote about Ruskin’s life using only the holographs conserved in the UK could not help but base their descriptions of his “issues” on materials capable of illuminating only parts of the story (and not the most important parts at that), the result being that the conclusions drawn could not help but be in significant error—such as a determination that John Ruskin was a pedophile.

A final irony resulting from the conspiracies should be noted: namely that, if Joan—who, whatever their difficulties may have been, adored her cousin—were alive, she would be horrified at what she and her co-conspirators had wrought. For, leaving aside the monetary ambitions she and the others had for the Library Edition, everything she did had been done for the good of her “beloved Coz,” had been undertaken by a heart hoping only to help, a textbook case of “the cost of good intentions” if ever one there was.13

Distortion

A recurring problem with essays like this is that, by nature, their scope is limited. Using intensely focused flashlights, we who wish to shed fresh light on an issue enter this or that room in our subject’s life or work. As we brighten a formerly dark corner, however illuminating our torch may be, inevitably we miss vital information housed in other rooms which, consulted, would contextualize our new findings better. In short, in the same moment they enlighten, concentrated studies also distort the complexity of their subject. Perhaps most worrisomely, given the pejorative nature of the charges against Ruskin, the distortion created by this reporting-from-a-neglected-room effect has been marked, because, whether those who were convinced of his disturbed sexuality were scholars or popularizers, their focus has been on the shocking, creating the impression, now pervasive, that sexual matters are the only aspects of Ruskin’s life deserving our attention.

Which in his case is decidedly not the case. While all the sexual issues discussed above were real enough, and while, on any given one or series of days, one or another may have taken center stage, in truth and overall, sexual matters played a relatively small role in his life.

John Ruskin in his Study at Brantwood, Dawn. W. G. Collingwood. 1885. Watercolor. Reproduced by kind permission of The Ruskin Museum, Coniston, Cumbria LA21 8DU.

Consider, for example, a typical day at Brantwood in the 1880s. After an early breakfast, Ruskin would repair to his study to compose new pages for the book(s), article(s), or lecture (s) on which he was working (not infrequently all three simultaneously). Later, this always first task set aside, he would turn to another quotidian responsibility, the writing of dozens of letters (some lengthy) to friends (dear and less so), to business contacts, admirers and supplicants, letters which, until this minute, had waited impatiently in stacks on the floor by his writing desk. However many he wrote, he never reached the bottom of the pile which, by the time the next morning arrived—as a result of the delivery of dozens of new missives—had returned to or exceeded its earlier height. In the afternoons (or at least those afternoons when he was capable of wrenching himself away from the petitioning letters), he would draw or paint (most often images he planned to use in his books or lectures). When in London, he would often travel to a nearby gallery or museum to study the art hanging there. Capital evenings would find him dining with friends, after which, as we have learned, he would not infrequently be off to the theater, the brief respite it offered from his responsibilities its principal lure. Lake District evenings would find him strolling in the woods surrounding Brantwood or watching, from some special vantage, the sun setting beyond the mountain across the lake known as the Coniston Old Man. As the day arrived at its end, Joan, her husband Arthur, their children, and any friends who might be visiting, were called to the drawing room where, by a cheerful fire, “The Professor,” as he was often called there, would read aloud from one of his favorites—most often the poems of Byron, Burns, or the novels of Sir Walter Scott and Dickens. When there was no one to whom he could read, Ruskin would return to his library and carry to his chair the literary works (Plato, Dante, Virgil) he considered, along with the Bible, the world’s greatest fonts of wisdom; or, if the following day’s work necessitated it, would study the supporting works he would need to expand or modify some argument made in his draft pages of this morning.

Or, using a different lens while keeping in mind the erotic topics that have been the focus of these pages, consider the main occupations of his earlier decades: that, during the late 1840s and early 1850s when his marriage was collapsing and the question of his sexual competency was bandied about London, he was, in addition to giving dozens of public lectures, composing no fewer than three acclaimed masterpieces: The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849; complete text), in which he laid out the principles that elevated a building from the mundane to the marvelous; the three-volume Stones of Venice (1851-3), wherein he contended that the marvelous floating city on the Adriatic had risen to world eminence as a result of its citizens’ subscription to the moral principles detailed by the Ten Commandments, after which, as those same citizens abandoned these sacred directives, it collapsed into license, ruin, and deserved disrepute, the story written as a caveat to Britain which, as he saw it, was, with much avarice aforethought, marching with alacrity down the road that had laid Venice low (readers loved his mellifluous paragraphs, but were not taken with the admonition); and the last volumes (III, IV, V) of his Modern Painters series (1856, 1859) in which he tried to make indelible the critical importance of generating great art in any society desirous of world repute.

The Author of “Modern Painters”. George Richmond. 1843. Watercolor. Source: Works, Frontispiece, volume 3 (Modern Painters I).

Or consider that, during the 1860s, when the excruciating tragedy of his love for Rose La Touche was unfolding, he wrote what must still be seen as some of the most important sociological works of the nineteenth century, Unto this Last, The Crown of Wild Olive, and Time and Tide, all no-holds-barred attacks on the cupidity which undergirded his fellows’ overzealous and uncritical subscription to the principles of laissez-faire capitalism. Or that, by the end of the same decade, his father John James having left a sizable fortune on his death in 1864 (close to $38 million in today’s dollars), Ruskin, believing the money tainted because much of it had come from businessmen he regarded as exploiters, had given it all away to charities or used it to buy great art which, before he died, would be gifted to the British Nation.

Title-page of the first book edition of Unto This Last from the author’s collection.

Or that, during the 1870s and 1880s, years which included the never-resolved death of Rose (1875) and the tenacious suffering attending his attacks of “brain fever” (the first occurred in 1878; others returned at approximately two year intervals), he published yet another three-volume masterpiece, Fors Clavigera, 96 lengthy letters addressed to the working people of England in the hope that—no longer having any confidence that his society’s elites would do anything to mitigate the ravages created by their Industrial Revolution and laissez-faire—he articulated principles and practices designed to help his less educated readers create a humane society of their own, that transformation being quicker if they joined his newly-created Guild of St. George, a group of like-minded souls dedicated to being scrupulously honest in their dealings, who would live in harmony with nature, eat foods they had grown, and wear clothes they had made while sitting on chairs they had fashioned. (The Guild still exists with branches in the UK and US. Both remain focused on discovering ways to manifest Ruskin’s vision of a good society.) Not to mention that, for most of these years (1869 onward), he fulfilled his duties as Oxford’s First Slade Professor of Fine Art (retiring in 1885 in protest over the university’s unwillingness to cease supporting the practice of vivisection), and the fact that, as the 1880s advanced and his strength, both mental and physical failed, he composed 28 chapters of still another masterpiece, his autobiography, Praeterita.

All these works were undertaken with a singular goal in mind: Ruskin’s unflagging commitment to teaching his fellows how, if they but looked carefully, and attended well in train of such looking, they would be enhance their own and their fellows’ happiness exponentially. The motive is clearly on display in the first of his Fors Clavigera letters, published in January, 1871: “I have listened to many ingenious persons,” he wrote there, “who say we are better off now than we ever were before. I don’t know how well off we were before, but I do know positively that many deserving people of my acquaintance have great difficulty in living under these improved circumstances, [and know] that my desk is full of begging letters, eloquently written by distressed or dishonest people and that we cannot be called, as a nation, well off while so many of us are living in honest or villainous beggary. For my own part, I will not put up with this state of things passively an hour longer.” (LE 27: 12-13; cf. LE 7: 9-10; 18: 61). A story is told where, after a lecture, a woman from the audience approached to say how much she had enjoyed the presentation. To which, Ruskin replied: “Thank you, Madam. But did it do you any good?”

In only a handful of these works does the issue of sexuality arise and, on these few occasions, we learn (not surprisingly by now) that Ruskin always is keen to put Eros into life-supporting, as opposed to self-gratifying, light. Some passages make it clear that he believed that, under appropriate circumstances, sexual love could play an important, even noble, role in life. Sexual coupling, he wrote in Modern Painters V, “when [it is] true, faithful, [and] well-fixed, is eminently the sanctifying element of human life. Without it, the soul cannot reach its fullest height or holiness. But,” he went on, when the sexual act is “shallow, faithless, [or] misdirected, it is also one of the strongest corrupting and degrading elements of life" (LE 7: 417). A reprise of the view is seen in his response to a letter received in Venice in 1877. Thinking of the power of sexual passion, his correspondent had suggested that, regarding the proper time for marriage, earlier was better than later. Ruskin differed: In your letter, he rejoined, you spoke “too exclusively of Lust, as if it were the normal condition of sexual feeling, and the only one properly to be called sexual. But the great relation of the sexes is Love, not Lust. That is the relation in which 'male and female created He them' [Genesis 5:2], putting it into them [so that] the brutal passion of Lust [would] be distinctly restrained into the office of fruitfulness…giving [each] the spiritual power of Love so that each spirit might be greater and purer by its bond to another associate spirit in this world and that which is to come: help-mates and sharers of each other's joy forever." (LE 34: 530. For sense, I have slightly rearranged this passage.)

The point is to note that, for Ruskin, an interest is sexuality per se is never of prime concern. Indeed, that it played even a secondary role was as often a result of the prurient interests of others who, in one way or another, had heard of the reason for the annulment of his marriage, or who, either because they could not resist the temptation to indulge in gossip or having anti-Ruskin axes to grind, refused to let titillating rumors die. In short, our practice of reducing Ruskin the man and Ruskin the author to the status of a once-famous eminent whose only contemporary interest is his supposed sexual penchant for girls is grossly distortive. Indeed, as the above outline of the arc of his days and work suggests, the fact that when Ruskin enters our conversations today and talk immediately shifts to remarks reproaching his sexuality, that reaction tells us more about our own cultural fixations than it does about the person rebuked. Which takes us to another irony: that (as mentioned at this essay’s start), while the importance of allowing scholars the freedom to take any direction they believe to be right in their search for truth must always be regarded as sacrosanct, the abundance of studies that have been focused on Ruskin’s erotic life in recent decades—including this one—are themselves outgrowths of our own erotic obsessions and, as such, however unintentionally, aggravate our seriously slanted view of him.

Hypocrisy

At the outset, I noted that our subject has been reproved not only as a sexual deviant but as a hypocrite, the second censure flowing from the first, thus: given the indisputable fact that all of Ruskin’s work is cast in moral frames, and it seems that at his core he was profoundly immoral when it came to his secret passions and treatment of women (especially young, vulnerable and innocent ones), then no other conclusion is possible: he was a hypocrite (an “actor,” a “pretender,” a “dissembler”: OED). From which it follows further that we should have nothing to do with him, save to go on denouncing him for his vulpine appetites. Hence, to read his works, let alone entertain any thought that we might take them seriously, would not only be foolish and a waste of time, it would be tantamount to a public declaration of support for the vilest deviant. It is, of course, an ad hominem argument, a tarring of someone’s work because a presumed flaw in his personal life. Notwithstanding the logical illegitimacy, however, the imputation has been extremely effective: for who, today, reads Ruskin?

But our earlier discussion has shown that Ruskin was not as his accusers alleged. Not only was he not a pedophile or the embodiment of some other sexual illness or neurosis, no evidence exists which would suggest that he ever wished harm on anyone; indeed, the opposite. Which findings not only invalidate the indictment of hypocrisy, it suggests that, if justice is to be done, we must now seriously consider the possibility that the tens of thousands of pages he published were genuine both in sentiment and argument. Consider in this light the following instances:

--Remarks included in a (previously unpublished) letter sent to Mrs. Mary Hewitt in 1859, remarks that also shed additional light on a topic earlier discussed, that, as far as Ruskin was concerned, an intimate relationship with a woman was never very high on his list of priorities: “I shall never devote myself to any woman,” he writes to this friend, “feeling—whether erringly or not—that my work is useful in the world and supposing myself to be intended for it. Call this haughty if you choose, but be assured I write my books from Pride—not Vanity. Because I suppose myself useful, not because I want to be admired. I desire no crown—but will not give up my labor—nor my soul, to any woman.” (PML VP: MA 5025: Year File: 1859)

--Or consider these comments in his book celebrating the beauty and significance of flowers, Proserpina (1881):

[T]he only power I claim for any of my books,” he says there, “is that of being right and true as far as they reach… They tell you that the world is so big, and can’t be made bigger, that you yourself are also so big, and can’t be made bigger however you puff or bloat yourself—but that, on modern mental nourishment, you may very easily be made smaller. They tell you that two and two are four, that ginger is hot in the mouth, that roses are red, and smuts black. Not themselves assuming to be pious, they yet assure you that there is such a thing as piety in the world, and that it is wiser than impiety. Not themselves pretending to be works of genius, they yet assure you that there is such a thing as genius in the world, and that it is meant for the light and delight of the world… [All these things] are comprehensible by any moderately industrious and intelligent person. [LE 25.416]

--Or, consider the following extracts from his sociological works. What if he meant (as he did) just what he wrote as he arrived at the last paragraph of the “Introduction” to The Crown of Wild Olive (1866), a collation of some of his most piercing arguments about the desperate need to create a more humane society. Should you decide to travel the path of mutual help outlined in previous paragraphs, he tells his readers, you would find the following benefits would emerge as a matter of course:

free-heartedness, and graciousness, and undisturbed trust, and requited love, and the sight of the peace of others, and the ministry to their pain. These—and the blue sky above you and the sweet waters and flowers of the earth beneath, and mysteries and presences innumerable, of living things—may yet be your riches, untormenting and divine; serviceable for the life that now is, nor, it may be, without promise of that which is to come. [LE 18.399]

What if he meant (as he did) what he said when concluding his lecture, “Traffic” (text) in 1864, a talk during which, with an intensity of impeachment uncommon even for him, he excoriated his audience (the doyens and factory owners of the thriving, smoke-enshrouded Midland city of Bradford) for their ignorant and willful despoliation of the beautiful British countryside and shameful exploitation of their city’s poorer citizens so that they might gain for themselves the excessive profits which would allow them to indulge their unquenchable desire for luxuries and excess. The committee which had invited him had done so hoping that he would speak as the renowned expert on architecture he was, hoped that he would help them find an attractive design for the new trade center they were about to erect in their city center. To which end, Ruskin said beginning his talk, he could not help them. However, he said, returning to this earlier avoidance as he arrived at his final sentences, I might be able to help if

you can fix some conception of a true state of human life to be striven for, life good for all men as for yourselves; if you can determine some honest and simple order of existence following those trodden ways of wisdom—which are pleasantness—and seeking her quiet and withdrawn paths—which are peace. Then, so sanctifying wealth into commonwealth, all your art, your literature, your daily labors, your domestic affection, and citizen’s duty will join and increase into one magnificent harmony. You will know then how to build well-enough. You will build with stone well, but with flesh better—temples made not with hands, but riveted of hearts—and that kind of marble, crimson-veined, is indeed eternal. (LE 18.458)

What if he meant (as he did) every word of the extract below, taken from “The Future of England,” a lecture delivered in 1869 at London’s Royal Academy. We pride ourselves, he said on that evening to an audience much like the one he faced in Bradford, on being the most productive, intelligent, and advanced nation on the face of the earth. If this is so, then how is it possible that our

cities are a wilderness of spinning wheels instead of palaces, yet the people have not clothes? We have blackened every leaf of English greenwood with ashes, and the people die of cold. Our harbors are a forest of merchant ships, and the people die of hunger. Whose fault is it? Yours, gentlemen, yours only. For you alone [have the power and wherewithal to] feed them, and clothe, and bring them into their right minds. For you only can govern—that is to say, you only can educate them. LE18.502]

Specifying—apropos this education—in another place: “In the simplest terms, my scheme of education is only that all the energies of the mind shall be founded on affection and benevolence, and that all the faculties of the body shall be developed in due time to healthy and balanced strength…” Adding: “my general wish [always is] to make all honestly living creatures happy, even [if doing so causes] some inconvenience to myself” (LE 35.628-29). As indeed it did.

Today, many find such passages and pronouncements of moral intent discomfiting. Living in our modern milieu, few trust that statements like those we have just read are genuine. As a result, when asked to entertain a thought that someone articulating such views is doing so guilelessly, having been often singed for trusting those in authority or others who have averred that they are only concerned for our welfare, straightaway we are suspicious and initiate the hunt to find the fly lurking in this purportedly heartfelt ointment, the result being that, whether the infectious insect is located or not, our culturally engrained misgivings and cynicism make it all but impossible to accept that someone who seems sincere is. Even if there is no actual hypocrisy, we think, at the very least veiled self-interest must be lurking somewhere.

There is another reason why we moderns shy away from Ruskin. We live in an amoral age. Judges, except on those few occasions when the most egregious or hurtful offence occurs (pedophilia), we want not to be. Encountering thought or behavior which, in an earlier era, would have been quickly seen as being offensive to either persons or the right to live freely and decently, we are often willing, even eager, to look the other way. “Chacun a son gout” (“To each his own”), we say, not wishing to get involved; hopeful, too, that by assuming such a non-judgmental stance, others might allow us a little moral leeway when it comes to some of our own peccadilloes.

Not only did Ruskin live in such a more ethically focused era, he was, by personal and religious conviction (see later discussion), never chary about critiquing, with neither qualm nor mincing of words, behaviors he thought inimical to wholesome social life. As we have just read, he never let his readers, or anyone attending his lectures, off the hook, always held their feet to the moral fire. During his time many hated—vilified—him for the impudence. Many in our own era don’t much like such audacity either. Sensing the presence of his critical eye and not keen on being caught in its gaze, it often seems like the happier path would be that which would give him wide berth; better to continue regarding him as a member of the disingenuous clan; there, at least, he is shorn of any ability to embarrass. (I will come back to this issue in Chapter Three.)

Blaming the Victim (The Impossibly High Bar)

Still we do not have an explanation for what I regard as the raison d’etre for the “out of hand” rejections of Ruskin and his work which continue their dogged reign in the academic and public realms. Regarding these dismissals, it is important to recognize that, no matter who the person may be who utters them, where that person lives (region or country), or where she or he falls in the social class spectrum, without exception, all share these traits:

(1) Almost none of those who reject Ruskin do so having any direct knowledge of his writings or any clear sense of what he was trying to accomplish by writing them;

(2) all but a fraction of the rebuffs source in hearsay; the faultfinder has heard from someone, somewhere that Ruskin was a nineteenth century moralist who, appallingly, possessed a sexual penchant for children and girls;

(3) this knowledge is sufficient to generate public subscription to the “Ruskin as persona non grata” position;

(4) once this stance is assumed, it is regarded by those embracing it as ethically (and, often, politically) correct; and

(5) such posturings are often virulent in intensity and impervious to challenge.

A little sociological analysis will help us understand the phenomenon.

Such non-reflexive, hidebound attitudes are a nearly perfect case of a cultural process which the sociologist, William Ryan, calls “blaming the victim,” a practice, common in many societies, where members of a dominant social group accuse an individual or group of harboring or expressing what they view as an egregious fault, a fault so serious that, if it is not curtailed or stamped out, it could threaten the stability of the whole social order. Sometimes the reproached possess the characteristics regarded as repellent, sometimes (as in Ruskin’s case) they do not. But whether they do or not is not, from the point of view of those reproaching, the point. The point lies in finding someone to tar with the offence, for, once the charge is brought, certain social and psychological benefits redound to the accusers and wider society. Specifically: such indictments give accusers the right to feel and regard themselves as morally superior to those nominated as miscreants. This sense of loftiness bestows other benefits: the liberty to dismiss out of hand any evidence or counterarguments which might suggest the indictment to be in error and reject any suggestions that the decriers themselves might possess, if even only to a lesser extent, the faults affixed to the reproached.

But the most important consequence of victim blaming, the reason it exists as an ongoing mechanism of social control, is how, once it is set in motion, it allows the shoring up of some aspect of life in the wider society which has become unmoored. Specifically, it allows for the relegitimation of status quo norms (“the rules for proper conduct”) that pertain to the behavior in question, and makes indelible in the minds of the accusers and in the minds of anyone coming into contact with either the accusations or accused, that the previously agreed upon way of doing things is the “right way of doing things.” That there needs to be an actual victim, and that untoward consequences always visit that victim, is of no immediate significance. Relegitimation of the threatened normative pattern is the objective.

For example, as students of crime have known since at least the time of Plato, punishment is never administered with any real commitment to reforming or redeeming the offender. It is administered as a warning to everyone else in the group not to break the rules pertaining to the accepted way of thinking and acting, for, if they do, the negative consequences that have descended on the victim blamed shall redound on them as well. Depending on the egregiousness of the offense, punishments can include public shaming, beating, hanging, or, in Ruskin’s case, in addition to ongoing vilification, ostracism from the company wherein he was previously accepted without reservation, namely in the realm of the culturally revered. Indeed, non-reformation of those identified as criminals is, from the perspective of the wider society, a positive outcome, because the unrepentant or recidivists underscore the correctness of the dominant norms and the accusations of degeneracy. Similarly, the harshness of the criticism leveled at an elected malefactor and the pain which she or he suffers as a result of the identification is symbolically useful, because, from the point of view of those damning, the wrongdoer “deserves what she or he gets,” a judgment that also endorses the dominant mode of thinking.

That the blaming the victim process is powerfully present when indictments of sexual decadence are directed at Ruskin is obvious. In his case, however, there exists yet another reason which accounts for the virulence of his discrediting: he has been accused of being a pedophile.

In our era of sexual permissiveness where the lines between the unobjectionable and the licentious, the mutually condoned and insensitive self-gratification, between erotic liberty and exploitive license, are blurred, there is much to be confused about concerning what designates appropriate erotic expression. It is in such an ambivalent social situation, Ryan says, that the need to find and blame a victim who will allow us to reset the acceptable boundaries for what is allowed and what is not starts to stir. Further, when the ambivalence centers on a fundamental process like sexual behavior in all its varieties, including its attendant, and critical, social ramifications (marriage, partnership, inheritance, having and bringing up children, others), the need to “keep the lid on” types of erotic expression which might weaken these other vital social arrangements becomes imperative. And so, if we can locate someone whose sexual conduct is so offensive as to defy any thought of tolerance, we can brand that person(s) as degenerate and, in so doing, make it clear to all that, under no circumstances, is this form of behavior allowed, because, beyond here, as the Chinese proverb reminds us, there be dragons.

Simultaneously, the nomination of someone to serve as a public instance of unacceptable sexual behavior allows us to set to one side many of our own erotic ambivalences, content in the knowledge that, whatever we may have thought or done regarding intimate matters, they pale in comparison to the transgressions of the designated. Pedophilic behavior, all agree, is behavior “beyond the pale” by virtue of its grounding in a consciously chosen wish to exploit and harm the weak, innocent, and young among us. Given that no society that allowed such behavior could be expected to endure, like premeditated murder, pedophilia is always seen as a step too far. Hence, whenever it is suspected that there is a pedophile is in our midst, someone needs to be chosen to occupy the category of the vile in order that this egregious tear in the social fabric can be repaired as quickly as possible.

Recall in this context the condemnations of Ruskin given at the beginning of this essay.14 In every case, the essential elements of blaming the victim are clearly on display: the obdurate visitors to the Ruskin Library who simply would not countenance the suggestion made by a Ruskin scholar to the effect that, whatever his erotic issues may have been, if one but took a little time to study them, his works would disclose a treasure trove of wisdom and humane concern; or the condemnatory remarks itemizing Ruskin’s supposed fixation on little girls which dominated Valentine Cunningham’s review of the second volume of Tim Hilton’s biography, a focus chosen by the reviewer despite the fact that Hilton devoted only a few pages of his 600 page book to the issue; or critic Adrian Searle’s laceration of our subject’s character in his review of an exhibit at Tate Britain celebrating Ruskin’s contributions to art; or the off-hand reference to Ruskin as a “sexual deviant” by David Barnes in a newspaper article which, otherwise, commended his work; or, finally, the intransigent reactions of the man with whom I discussed Ruskin’s sexual interests in a Coniston pub. In all instances, Ruskin was seen as a miscreant of the most despicable sort.

Indeed, as we bring these examples back to mind, we begin to notice that, in content and tone they are, despite the facts that the denunciations were voiced at different times in widely dispersed geographic locales by people who did not know one another, virtually identical. It is as if Ruskin’s decriers had been instructed about how they must react when the topic of pedophilia arises, as indeed, as a result of their earlier socialization regarding what are the categorical instances of unacceptable sexual behavior, they have been. Such virulent and parochial reactions also explain why attempts to counter the accusation of pedophilia hardly ever succeed and why any contrary evidence offered in the accused’s favor is rejected. The pedophile (Ruskin) is not the real issue; the instance of perverse sexuality is. The person is but the symbol of that perversity, the required sacrifice, someone who can be held up to public view as having gone down the path of the unthinkable.

Very little of the blaming the victim process operates consciously. Almost no member of any society, sociologists tell us, grasps that the bulk of her or his thoughts and actions have been conditioned by virtue of the fact that they have been taught what to think and when to think it because they are members of a particular group (in reality, dozens of groups). Each believes they think as they do because of their own independent choices. In reality, if one but looks even lightly, it is palpably evident that the great majority of any coherent group’s members think and act alike most of the time. Examples are endless: To take political affiliations only: in America, Republicans and Democrats; in the UK, Labor, Conservatives, and Liberal Democrats. Such is the power of an internalized non-conscious ideology (Bem and Bem).

Ruskin, we have been told by those who seem to know, was a thoroughly bad fellow regarding matters sexual. Hence, no one in our group who has any respect for human decency should have anything to do with him. So informed, it is as though each becomes a member of an invisible choir whose members are expected to sing a predetermined tune on predetermined cue. Experiencing that cue, all those who have heard the “reprehensible Ruskin” story, assuming the (unexamined) accusation to be true, repeat, as they meet uninformed others, the tale, and in this way the blame spreads and the victimization deepens.

On the face of it, the dubiousness of repeating insubstantial reports of scurrilous behavior seems evident. But the real issue, as earlier said, is not veracity, but the desire that all hearing of the offence, condemn it, so that the boundary specifying what is sexually unacceptable in an era of widespread sexual ambiguity can be revivified. The need for unshakable demarcation trumps any desire to learn the actual truth of the allegation. Indeed, in such situations, that truth, especially if it is contrary to the accusation, is unwelcome. (“We don’t want to hear what you have to say. When it comes to matters of sex, Ruskin was a very sick man, and we will continue to believe this even if what you offer as an alternative interpretation is reasonable!”)

Consider it from the point of view of Ruskin’s accusers. If it is accepted that he was not as corrupt as posited, who will serve the function of re-legitimating the boundary informing us of what is permissible and reprehensible vis-à-vis sexual expression? If the victim who symbolizes the forbidden vanishes, we are forced back into the state of confusion that reigned previously and must ferret out a new victim to take the place vacated by the one liberated. Which in Ruskin’s case would not be easy to do because, in a very real sense, he is the perfect victim to blame because of his former cultural celebrity, a celebrity that makes him into a considerably more noteworthy offender than would be the case with miscreants of lesser luminance. In the same way, Ruskin has broad appeal to a spectrum of social “judges.” Recall again the examples I provided of his disdainers: a group of British tourists, an Oxford professor, an art critic, a newspaper writer, and a working class man in a Coniston pub. Consider as well the charge: pedophile. While, as a society, we (rightly) abhor pedophilia as the foulest sort of behavior, when real pedophiles having no wide social prestige appear on the public stage, not long after the aspersions have been cast, they are forgotten. Ruskin’s fame provides us with the ability to use him as an enduring symbol of depravity. In other words, not just any pedophile will do.

Which brings us to the final aspect of the blaming the victim process. Namely that, once it is initiated, it erects a kind of invisible cultural “bar,” a bar all but impossible to clear no matter what evidence is brought to bear suggesting that the accusation is false. Think of it from the point of view of the wider social order: if the label of sexual perversion attached to Ruskin is to be removed, it can only happen if it can be demonstrated beyond doubt that his life was utterly pristine when it came to the expression of harmful sexual behavior (it was), and that his mind was utterly pure when it came to thoughts concerning corporeal relations (it wasn’t). And, if this is the standard for exoneration, is it not one which none save the saints (and, reasonable reports suggest, not all of them) can meet? For who among us—leaving Ruskin out of consideration for a moment—could ever pass so stringent a test? Who has not entertained some lustful thoughts, not merely for those who comprise our expected and socially-approved intimates, but for others who might not as easily fit into this approved category? Such expectations defy the lived experience of all but the tiniest handful of human beings. Given this—and bringing our subject back in—if this is the bar which Ruskin must get over if he is to have any chance of leaving the cell of the depraved into which he is locked, might it not be likely that he may never be released, that he has stood convicted without possibility of parole from the moment he was first unjustly labeled a pedophile, and that, in the decades which have elapsed since, it is his status as a symbol of the perverse that we prize, a symbol which, because it re-establishes the boundaries of the sexually inadmissible for us all, we are loath to relinquish? I will come back to this disconcerting possibility.

Ruskin’s Choice

We turn to a consideration of other aspects of our subject’s sexual story not yet discussed. Now that we know that Ruskin was not the debased soul many still believe he was, there can be no arguing the fact that, during his time, the constricted sexual life he lived was far from the cultural norm. Second, abundant evidence (some of it already considered) informs us that, during those times when his sexuality became a matter of public discussion, he was often severely criticized, even disdained, for living away from that norm. Third, we have still to understand the process by which Ruskin worked out for himself what his sexual path would be. And fourth, after we have grasped the principal elements of that process, we will understand clearly why his choices played into the suspicion of some modern critics that he was a shameful sexual deviant.

I have not—again let me say with insistence—written [about] any of [the things which appear in my books] because I especially loved them. I hear it often said by my friends that my writings are transparent so that I may myself be truly seen through them. They are so, and what is seen of me through them is truly seen. Yet I know no other author of natural candor and passion who has given so partial, so disproportioned, so steadily reserved a view of his personality. [my emphasis] Who could tell from my books, for instance, but by the shrewdest (and, at its shrewdest, often failing) analysis,-what power the beauty of women had over me, who could trace what has been the course of religious effort and speculation in me? Who could learn anything of my friendships or loves and of the help or harm they have done me? Who could find the roots of my personal angers? Or see the dark sprays of them against the sky?

The above sentences can be found in the draft Preface Ruskin wrote as an introduction to the second volume of his book on botany, Proserpina. Composed in 1881, he had recently recovered from his second bout of “brain fever,” an attack that included, as had the first three years prior, a psychotic episode, a time during which, for some weeks, he lost contact with reality. So severe were the attacks, it was not evident to friends, doctors, or Ruskin himself, even after the most severe effects had waned, whether he would be able to write, or live, much longer.

Self-portrait in Blue Neckcloth. John Ruskin. 1873. Watercolor. Courtesy of the Peirpont Morgan Library, New York. Click on image to enlarge it.

Proserpina was a project unfinished at the time of the first onslaught. Now, in 1881, his recovery apparently thorough and feeling himself again, he was eager to finish the book, especially given the threats of final curtailment or incurable madness always hovering at the back of his mind. It was in such a context, perhaps not surprisingly, that he took some moments to reflect, in the sentences above, on the path his work had traveled over the four decades.

As it happened, other severe brain storms in later years and new projects rising to usurp its place, Proserpina never was completed. The Preface for the second volume did not appear until 1908 and, even then, was printed as an appendix at the back of the volume of the Library Edition containing Ruskin’s autobiography, Praeterita, using an invented title, “The Author’s Character and Teaching” (LE 35, 628-29). But there the whole of the passage just cited did not appear: the bits in regular type did, as did the lines italicized; but the crossed-out passage was excised. Examining the holograph, the reason for excision is apparent: Ruskin himself deleted the line, likely during a re-reading of his draft.

It is an intriguing edit, because it appears that, in sentences purporting to tell his readers of the assiduous care he has exercised in keeping personal revelations out of his work, it is as if he realized that, if he incorporated this remark, he would be admitting more than he wished. Of particular significance is what has been expunged, a remark about his attraction to the beauties of women—not (especially notable given the focus of this essay) a remark celebrating the beauties of children, girls, or young women. These latter he had extolled earlier in work after work, letter after letter, but of this attraction to women, nothing had been said. A little noticed letter to Norton points us in a helpful direction for understanding why this might have been the case: “I have a little eight year old girl,” he explained to his American friend on July 15, 1873, “my goddaughter, Venice, whom I hope to lick into something. She is strong and runs the hills like a rabbit.15 But the deadly longing for the companionship of beautiful womanhood only increases on me; the want of it seems to poison everything… I think [anyone who] was pretty and loved me would do—but then I never should believe any more that [anyone could] love me.”17 These remarks and the pointed deletion in Proserpina’s Preface suggest that it may not be time ill-spent if we consider in more depth a conclusion made at the end of the first chapter: namely, that Ruskin, as he always averred, was sexually normal--and, for that reason, was frequently attracted to beautiful women.16

Earlier, we saw how assiduously he worked to guarantee that any sexual attraction he might have had for one or another of his pets was closely controlled, always making it clear in his letters that what passed between them, however “suggestive” some exchanges might have seemed, was but teasing, enjoyable expressions of “Love, within proper limits.” In the same way, he took pains to maintain at arm’s length any emotional attachments which may have existed between himself and the handful of adult women who became his closest confidants—usually by proposing, relatively early in the relationships, a series of familial sobriquets which they could use when addressing each other. Dickinson (Ch. II) argues—rightly I believe—that a key reason for the practice was to actualize Ruskin’s desire to create in fancy an intimate “family” which would substitute for the lack of same in his childhood.19

What I suggest here is that there was another important objective in the practice. Thus, Joan Severn, his married, caretaker cousin, became, as we have seen, “Di Ma” (“Dear Mother”) to his “Di Pa” (“Dear Papa”); while Lady Mount-Temple (married) became “Grannie” to his “loving little boy.”17 In the same vein, Lady Simon (married) became “S” (“Sister” or “Sybil”) to either his “JR” or “Oldie,”20 while the widow, Lucia Alexander, became “Mammina” as her unmarried daughter, Francesca, became his beloved “Sorella” (“Sister”). In other relationships with adult women, Fanny Talbot (married) was “Dearest Mama Talbot” and Dora Livesey, one of his original pets at Winnington Hall, became, once she had wed, “dautie” (“daughter”).”20 Dickinson (Chs. II, III), in her discussion of the nicknames and “baby talk,” argues that Ruskin’s pets and women confidants happily acquiesced to the re-namings because of their love and respect for him or, in case of lesser intimacies, because they didn’t want to jeopardize their relationship with him. In addition, just so there would be no mistaking the nature of their relationship, many of the letters Ruskin sent to these women he would sign, “Childie.” Here is a particularly clear example of the practice: In 1874, he then 55, he initiated what would become a long friendship and exchange with his Coniston neighbor, Susie Beever (never married). In one of the first letters in the series (sent from Rome on 24 May), he wrote: “I have your letter of the 14th, telling me your age. I am so glad it is no more. You are only thirteen years older than I, and much more able to be my sister than mamma…” (Ruskin, Hortus: 8).

Susan Beever. W. G. Collingwood. Watercolor. With the Kind Permission of the Collingwood Society and the Special Collections Department of the Cardiff University Library.

Some of these women were beautiful in a conventional sense, some were not. But whether or not, Ruskin’s intent in inventing the nicknames and family designations was the same as it was with the distancing mechanisms he used with his pets, his desire to keep resolutely at bay in everyone’s mind any thought that sexual allure might play a part in the relationship. The flip side of the equation was as important: aware that he was sexually capable and sometimes attracted, by using the sobriquets, he regularly reminded himself that any erotic impulses he experienced were not to be indulged. It was a law, one as strict as any ever set down by God: one does not become sexually involved with one’s “Di Ma,” “Grannie,” “Sorella,” or “dautie.” It was a brilliant framing, for whether Ruskin was conscious of it or not, what social scientists call “the incest taboo” is a universal sexual ban present in one form or another in all societies, a proscription that becomes so deeply internalized in childhood that, quite literally, it depresses any erotic impulses that members of a family might feel for one another. It is a prohibition rarely broken, but which, discovered, is harshly sanctioned with an intensity not unlike that visited on those designated as pedophiles.

In only a few of his long-term relationships with women did Ruskin fail to invent a nickname. But in each case he invented ways to keep his distance. Examples: (1) Over the course of more than a decade and a half (1848 until her heart-breaking and sudden death in Switzerland in 1865 where Ruskin had been traveling with her and her husband), he had a prized friendship with Lady Pauline Trevelyan; their correspondence shows that he never addressed her as other than “Dear Lady Trevelyan” (Surtees, Reflections); (2) he maintained a similar (if less intense) friendship with the very beautiful Louisa, Marchioness of Waterford that lasted two decades (1853-1873); their letters tell us that, when writing, he employed the same formal salutation he used with Lady Trevelyan; (3) an unmarried wealthy woman three years his senior, Ellen Heaton, approached in 1855, the year following his annulment, to ask him about how she could be made an expert in the purchase of “good art”; for the next nine years, they corresponded; in all but a handful of his letters, she was addressed as “Miss Heaton”; (4) also in 1855, he was contacted by the unattached Anna Blunden, 26, asking for art lessons; he obliged; three years later, she told him she was much in love; in no way returning the sentiment, he told her so in no uncertain terms by return letter, only one of two where she is addressed as “My dear Anna” instead of the usual “Dear Miss Blunden” or “My dear Miss Blunden.” A sentence in the letter expresses the sentiment which defines his stance in all such relationships: “You fancy yourself in love with me…” he wrote on 20 October 1858, “writing letters full of the most ridiculous egotisms and conceits… There is no such thing as Platonic love. You may be my friend as much as you like… [But] love me, except as my friends love me, you must not.”21

“There is no such thing as Platonic love.” In using the phrase, Ruskin is telling this admirer that, as far as matters of sexuality are concerned, he is like any other. But having said so much, in the next breath he closes any window that might have suggested that such connections were welcome. Unless sexual relations occur within a proper relationship (i.e., between married people who love each other), he is having none of it. A final example illustrates the lengths to which he would go to ensure that the barriers he erected between himself and any woman who might be sexually available or interested would never be breeched.

Kate Greenaway. Albumen cabinet cardby Elliott and Fry. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG x15155. Click on image to enlarge it.

Earlier we read something of Ruskin’s relationship with the artist Kate Greenaway whom he had met in 1879. In what follows, I summarize a key theme in the nearly 600 letters Ruskin wrote Greenaway over the course of an exchange which lasted between 1880 and 1887 (after which, his recurrent mental attacks put an end to communication). The letters, extremely important for telling the story of Ruskin’s last working decade, have been available at PML since the mid-1960s. To my knowledge, other than myself and Helen Viljoen (and, earlier, Wedderburn), no biographer or scholar has read the set. The present discussion focuses primarily on missives exchanged between 1881 and 1884. Less than a dozen of Greenaway’s letters to Ruskin, originally greater in number than those he sent her, survive. Some (see discussion) Ruskin destroyed because of what he deemed their intemperate, ardent nature. The vast majority were burned, with Greenaway’s permission, by Joan Severn in another of the latter’s attempts to keep Ruskin’s reputation pristine after his death (for the surviving letters between Joan and Kate, seeRL L64). While some letters to Greenaway appear in the Library Edition (principally in LE 37), any holographs containing comments that might have alerted readers to the possibility that romance between the principals may have existed (an impression which Joan very much wished to keep at bay) were either not published or were presented in bowdlerized form. While the lack of Greenaway’s missives is unfortunate, Ruskin’s are sufficiently expressive to verify what follows. All excerpts are published here for the first time.

Once he studied her applauded paintings of children, Ruskin realized that he could use Greenaway’s considerable talents to illustrate themes he wanted to develop in works he knew would be his last, knew that she could illustrate, and beautifully, his argument that innocent, God-faring, joy-filled days were the true heritage God wished for the beings which had been created in His image (for the development of this focus, see Wyndham, 20-21). That message, combined with his insistence that it was each individual’s responsibility to do all in his or her power to bring such days to life, was what he wanted to communicate last. His use of Francesca Alexander’s work and stories in his later books (see LE 32: Parts I-II) was another key aspect of this “late life plan.” All of Ruskin’s biographers have overlooked or never taken seriously this plan—except as another index of his mental decline. How could the great art critic, John Ruskin, the champion of Turner, Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese, laud the work of such “lesser” artists as Kate Greenaway and Francesca Alexander? Surely it is but another index of his fading sanity.