John Ruskin (1819-1900) died on 20 January 1900 shortly before his 81st birthday at Brantwood, his Lakeland home for the last twenty years of his life, overlooking Coniston Lake and village, with the Old Man, one of his favorite hills, in the distance.

From left to right: Two Self-Portraits by Ruskin and a lithograph based upon a photo-

graph taken later in life. [Click on thumbnails

for larger images.]

Events in the centenary year of his death were coordinated and given impetus, under the umbrella of Ruskin To-Day, (To-Day was Ruskin’s own motto) by a small, dedicated group chaired by David Barrie, with joint secretaries Cynthia Gamble, Ruth Hutchison and Christopher Newall. The year began with a ceremony at Ruskin’s grave in Coniston churchyard on 20 January, a service of commemoration in the parish church, a special exhibition at the newly furbished Ruskin Museum in Coniston and other activities at Brantwood. The Ruskin centenary year has spawned a range of Ruskiniana, including books, a BBC Omnibus film about Ruskin, conferences at the Universities of Oxford and Lancaster, festivals, lectures and study days at Brantwood, exhibitions in Britain, the United States and Japan. The books include well-researched biographies such as Tim Hilton’s John Ruskin: The Later Years (review) and John Batchelor’s John Ruskin: No Wealth but Life; Michael Wheeler’s scholarly Ruskin’s God (1999), richly illustrated John Ruskin: A Life in Pictures by James Dearden and Ruskin’s Venice: The Stones Revisited by Sarah Quill; Robert Hewison’s Ruskin’s Artists, Sharon Weltman’s Ruskin’s Mythic Queen and Dinah Birch’s edition of Fors Clavigera. I did not see any Ruskin memorabilia, such as ties, shirts or coffee mugs, perhaps a missed commercial opportunity. Ruskin was elected the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in 1869, and it was most appropriate that the Slade Professor in 2000 was the Ruskin scholar and critic, Robert Hewison, who delivered a series of public lectures entitled “Ruskin To-day”.

Of all the many exhibitions and displays, the blockbuster was undoubtedly Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, with approximately 260 exhibits in ten rooms, seen by over 87,000 visitors between 9 March and 29 May 2000. It enjoyed the magnificent setting of the Tate Gallery, founded in 1897, which was renamed Tate Britain half way through the exhibition, to distinguish it from the new Tate Modern which opened in May 2000 in the redeveloped Giles Gilbert Scott power station at Bankside on the south bank of the river opposite St Paul’s Cathedral.1 Tate Britain is now resplendent with newly landscaped gardens and trees facing the river Thames and on the west side in Atterbury Street: the whole building has been cleaned and is sparkling white. Robert Hewison curated the exhibition working closely with Ian Warrell from Tate Collections, and Stephen Wildman, curator of the Ruskin Library, Lancaster University. The exhibition’s designer was Richard MacCormac, architect of the Ruskin Library, and the dramatic colour effects in a large open-plan area with walls of barn red, cane yellow, soft black, hippy purple, maize and damson were the work of Jocasta Innes.

Turner's Slave Ship. [Click on thumbnail for larger image and additional discussion of this painting.]

A Tate poster advertised Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites as “making new waves at the Tate” and “the work of Britain’s original new wave artists” against a backcloth of the agitated seascape of Turner’s Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhon coming on, from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, thereby suggesting the main focus to be on Turner. But that was misleading since, in spite of the tri-partite title of the exhibition, Ruskin, the least well known to the general public as an artist, was the pivot upon which the exhibition turned. It illustrated the key events of his long life and the currents contributing to his sometimes erratic aesthetic tastes, his whims as a collector and his eccentric moral and financial support for particular artists. He amassed a vast and disparate collection of works of art and seemed to delight in being a powerful and judgmental patron of artists often attempting to dominate and influence their tastes.

Three central members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood drawn and painted by Holman

Hunt (from left to right): D. G. Rossetti, Hunt himself, and J. E. Millais. [Click on thumbnails

for larger images.]

The exhibition was packed with a dense and intricate network of connections and interconnections. I felt as if I was in a labyrinth and could not easily extricate myself from these threads, and had to return again and again to Ruskin as the pivot. Ruskin’s admiration for Turner is perhaps most easily understood but the links with the Pre-Raphaelites are more complex. Who were the Pre-Raphaelites? Were they really represented by the collection of varied paintings on display? A reminder of the origins and intentions is called for. The name “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”, was chosen by three, young budding artists, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82), William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) and John Everett Millais (1829-96), while poring over a book of pictures of Benozzo Gozzoli’s and Orcagna’s Pisan frescoes at Millais’s house in Bloomsbury in 1848. Holman Hunt recalled the circumstances in an article in the Contemporary Review in 1886.2 A fairly naïve and simplistic doctrine, — breaking away from what they considered the stultifying art teaching of the day, — a desire to represent their subject matter truthfully, earnestly and with simplicity, bound the trio together, at least for a short period of time, under the acronym P R B, a useful marketing tool which remarkably has stood the test of time. Their common purpose and almost religious intensity was reflected in the choice of “brotherhood” with its overtones of a monastic order. Hunt explained that the choice of Raphael as a cut-off point was agreed “in a little spirit of fun”. Ruskin considered that the PRB was an “unfortunate and somewhat ludicrous” name.3 From it the name Pre-Raphaelites evolved, became generalized and difficult to define as more and more artists were placed, or placed themselves, under that convenient umbrella term. Ruskin sprang to the defence of the PRB cause in 1851 (and in 1854) with letters to The Times, believing that their aims embodied his own (CW 12: 319-27; 328-35). Inevitably, the original ideas associated with the PRB changed, but the name Pre-Raphaelites remains as representing Victorian art with its use of bright colour, purple especially, attention to detail, a predilection for religious and mystical themes, Arthurian legends, and other historical romances as depicted by writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-92), John Keats (1795-1821) and Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832).

The centrepiece of the exhibition was, for me, Turner’s Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhon coming on coming on, which would have merited a wall space on its own. It was first shown at the Royal Academy in London in 1840 when it was both derided and praised by critics as “the most tremendous piece of colour that ever was seen”, or “a passionate extravagance of marigold sky, and pomegranate-coloured sea, and fish dressed as gay as garden flowers in pink and green”.4 Ruskin himself described it in his first volume of Modern Painters (1843) as “the noblest sea that Turner has ever painted” and demonstrated this in his celebrated “purple passage” in which he conveys with intensity of colour and mood the situation of the guilty ship and the jettison of live slaves for monetary gain:

It is a sunset on the Atlantic, after prolonged storm; but the storm is partially lulled, and the torn and streaming rain-clouds are moving in scarlet lines to lose themselves in the hollow of the night. The whole surface of sea included in the picture is divided into two ridges of enormous swell, not high, nor local, but a low broad heaving of the whole ocean, like the lifting of its bosom by deep-drawn breath after the torture of the storm. Between these two ridges the fire of the sunset falls along the trough of the sea, dyeing it with an awful but glorious light, the intense and lurid splendour which burns like gold, and bathes like blood. Along this fiery path and valley, the tossing waves by which the swell of the sea is restlessly divided, lift themselves in dark, indefinite, fantastic forms, each casting a faint and ghastly shadow behind it along the illumined foam. They do not rise everywhere, but three or four together in wild groups, fitfully and furiously, as the under strength of the swell compels or permits them; leaving between them treacherous spaces of level and whirling water, now lighted with green and lamp-like fire, now flashing back the gold of the declining sun, now fearfully dyed from above with the undistinguishable images of the burning clouds, which fall upon them in flakes of crimson and scarlet, and give to the reckless waves the added motion of their own fiery flying. Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shadow of death upon the guilty ship as it labours amidst the lightning of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood, girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror, and mixes its flaming flood with the sunlight, and, cast far along the desolate heave of the sepulchral waves, incarnadines the multitudinous sea. [CW 3: 571-72]

This was the much-wanted oil which Ruskin’s father gave him as a New Year present on 1 January 1844 and which he later sold to the American collector J. T. Johnston, feeling unable to bear the subject anymore. In a letter of 28 January 1872 to Charles Eliot Norton, his close friend in Boston, he expressed his satisfaction with the painting leaving for America: “It is right that it should be in America, and I am well pleased in every way” (CW 37: 689). Controversy surrounded it in the United States and the Bostonian press generally expressed disapproval. The “intelligent and accomplished American artist”, George Inness wrote:

Turner’s Slave-Ship is the most infernal piece of clap-trap ever painted. There is nothing in it. It has as much to do with human affections and thought as a ghost. It is not even a fine bouquet of colour. The colour is harsh, disagreeable, and discordant.5

Mark Twain, in A Tramp Abroad (1880), recorded that “a Boston newspaper reporter went and took a look at the Slave Ship floundering about in that fierce conflagration of reds and yellows, and said it reminded him of a tortoise-shell cat having a fit in a platter of tomatoes”.6

The antagonistic and sarcastic comments arouse to some extent from what was perceived to be the discrepancies between Ruskin’s famous hyperbolic description and the actual painting. But it was forgotten that Ruskin was defending Turner with all his energy and had to convey in prose the vitality of his art without the help of any illustrations whatsoever in volume one of Modern Painters. Ruskin explained in a letter in 1847 to the Rev. Walter L. Brown, his former tutor at Christ Church, that this passage was not a description but an interpretation of Turner’s intentions, “to give motion to his colours” and make the viewer “see and feel the heaving of the sea” (CW 36: 81). The controversy may also have been sparked by a feeling of rebellion against the dictates of an English critic (Hamerton, p. 290).

The closer one looks at the detail in this painting, the more frightening and terrifying it becomes as forms take shape. In the foreground there is a tethered foot released by the tempest, a ferocious fish is attacking a human leg, black chains with their human cargo are about to sink deep into the ocean, starving scavengers are swooping down. It would not have been easy to live with. Turner did however remark that Ruskin saw more in his pictures than he ever painted, a charge that could well be levied against some critics today.

The development and output of Ruskin the artist was well documented. He learned to draw by copying, in particular works by Samuel Prout (1783-1852), Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) and Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding (1787-1855). The exhibition provided a rare opportunity to see originals and copies side by side, for example Copley Fielding’s Loch Achray next to Ruskin’s copy of c.1834-5, and Turner’s Christ Church College, Oxford (c. 1832) alongside Ruskin’s Christ Church from St Aldate’s, Oxford (1842). Ruskin continued to copy, often, and this was the basis of his own art teaching. His fine copy made in 1874 of Zipporah, from Botticelli’s fresco The Trials of Moses in the Sistine Chapel, Rome, demonstrated his attention to detail, the accuracy of his work and his “ability to paint a life size figure to [his] tolerable satisfaction in 14 days”.7

Christ Church College, Oxford by Ruskin.

A kaleidoscope of Ruskin’s own visual output of 1844-82 was displayed in a large central room demonstrating his basic tenet of learning by drawing, learning by doing. Many of his drawings were created as teaching aids or to illustrate some didactic statement in his books. The subject range was impressive, covering geology, ornithology, architecture, botany, meteorology and zoology. An inveterate traveler in France, Italy and Switzerland, Ruskin seized every opportunity to record places visually and in his writings. “The whole of Northern France [. . . ] is to me a perpetual Paradise”, he declared in volume four of Modern Painters (1856) (CW 6: 419). His Northern France included Picardy and Normandy, Provinces to which he returned time and time again, often in the steps of Turner following the course of the Somme or the Seine. Amiens and Rouen were the subjects of The Bible of Amiens and The Seven Lamps of Architecture (full text) respectively. There was no recognition of the importance of Amiens in the exhibition, but Ruskin’s watercolour Rouen: the Seine and its Islands from Canteleu was an example of his almost impressionistic work during the 1880 tour.

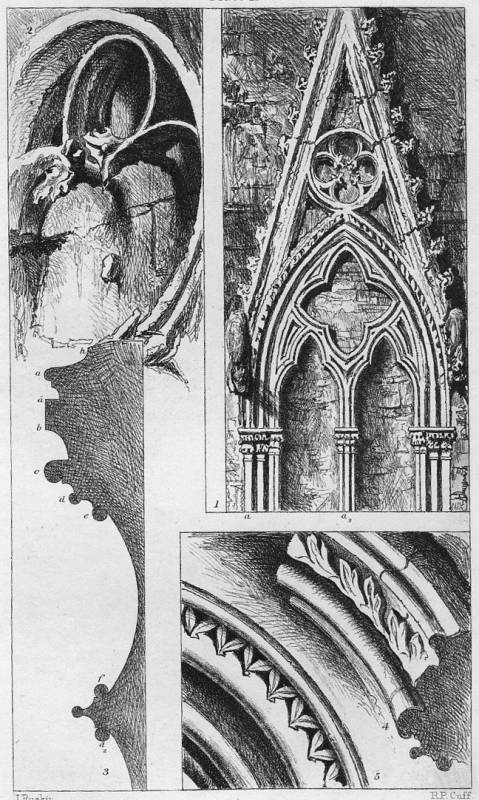

Some of Ruskin's drawings for The Seven Lamps of Architecture (from left to right): Niche

from the central gate of Rouen, Traceries and Mouldings from Rouen and

Salisbury,

Sculptures from the Bas-reliefs of the North door of the Cathedral of Rouen. [Click on

thumbnails

for larger images.]

Abbeville, “the preface and interpretation of Rouen”, was important to Ruskin and his watercolour of Abbeville: Church of St Wulfran from the river was one of several painted during his month’s stay in 1868 (The Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster). This fine watercolour shows the majesty of St Wulfran, the intricate architectural detail and its position in harmony with the river and the bridge in the distance with houses clinging to it, almost in need of protection. Yet signs of neglect and destruction are apparent: a large upper window is missing.

John Ruskin, Church of St Wulfran from the river. 1868 .The Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster.

The Abbeville Ruskin knew, and to which he frequently returned, was unlike the town today. Abbeville (like Amiens) was an important center for the French Resistance and in May-June 1940 the town suffered intense bombing by the Luftwaffe causing widespread destruction and loss of life. During the raids, the nave and chancel vaults of the Church of St Wulfran collapsed and there was extensive damage. Ruskin’s sketches and descriptions of the streets and buildings of Abbeville, with his attention to minute detail, provide an invaluable and accurate historical record over fifty-three years between 1835-88.

Ruskin recalled his first reactions to Abbeville on 5 June 1835 as a mixture of “immediately healthy labour and joy”. Catholic Abbeville was a source of happiness and inspiration to the sixteen-year-old youth, providing him with a powerful incentive to work and a release from his repressed feelings. He enjoyed a rejuvenating and exhilarating freedom which he had not known in the puritanical churches and chapels of South London, and expressed his delight in his fragmentary autobiography Præterita:

From here I saw that art . . . religion, and present human life, were yet in perfect harmony. There were no dead six days and dismal seventh in those sculptured churches; there was no beadle to lock me out of them, or pew-shutter to shut me in. I might haunt them, fancying myself a host; peep round their pillars, like Rob Roy; kneel in them, and scandalize nobody; draw in them, and disturb none. [CW 35: 156]

Ruskin’s memory of Abbeville in 1835 was of “the faithful old town [which] gathered itself, and nestled under their buttresses like a brood beneath the mother’s wings; . . . breezy ramparts, with their long waving avenues . . . navigable river and active millstream, the green chalk of the Somme” (CW 35: 146-47)

Each room in the exhibition had a large caption high on the wall, a fragment of Ruskin’s thought, almost an aphorism which guided the visitor, set the tone and which even the most hurried viewer could later recall. One of the most poignant rooms was No. 9, The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century, echoing Ruskin’s eponymous lectures delivered at the London Institution in February 1884 (CW 34: 1-80). Its deep purple backcloth mirrored Ruskin’s darker and more pessimistic view of the world from the 1860s. It charted, in a series of portraits, his hopeless love for the young Irish girl, Rose La Touche, both her and his tortured minds, and her death in 1875 at the age of 27. Ruskin’s heart-rending cri de cœur “Why did not our God make me but a little stronger — her but a little wiser — both of us happy?” which dominated the room had a Shakespearian dimension, “Of one that loved not wisely, but too well”.

At times it was difficult to reconcile the contradictions in Ruskin’s tastes. Even Millais’s portrait of John Ruskin 1853-4 hinted at a contradiction: the well-dressed man was standing rather rigidly by a waterfall in Scotland, inappropriately attired. Yet in spite of that stylised effect, it reminded us of Ruskin’s great knowledge and love of nature and geology, and that he was also an inveterate walker and climber.

As patron and collector, Ruskin’s taste was eclectic and included Andrea del Verrochio’s The Madonna adoring the Infant Christ, bought in 1877; Bartolemeo Vivarini’s Virgin and Child acquired in 1878: I find it a very ugly painting and ugly child. Botticelli’s Virgin and Child; Vincenzo Catena’s Portrait of the Doge, Andrea Gritti bought in 1864; D. G. Rossetti’s Paolo and Francesca da Rimini to name but a few. John Frederick Lewis’s A Fiesta Scene in the South of Spain- Peasants etc., of Granada dancing the Bolero (1837), the pride of Herne Hill, the Ruskins’ family home, was a strange example of taste, with its Spanish dancers and on-lookers, especially bearing in mind the absence of human beings in Ruskin’s drawings.

Ruskin helped several struggling artists, including D. G. Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862), by commissioning works or by paying a salary. He paid Siddal a sum of £150 a year without putting her under any pressure to produce any specific work: his letters show how much he did not want her to feel any sense of obligation towards him. He was concerned about her delicate health and paid for her to have a holiday in the south of France in order to recuperate. Ruskin arranged with Rossetti to buy whatever he produced, if he happened to like it: he also gave a money-guarantee to Smith, Elder and Co. to secure the publication of Rossetti’s translations from Italian. His generosity was not entirely altruistic, since Ruskin was more able to exert control over them and impose his views, for he possessed an almost pathological urge to dominate and teach: many of his letters to Rossetti are dictatorial in the extreme. Inevitably, the artists rebelled against this. Rossetti’s Dante’s Vision of Rachel and Leah (Tate Britain) was commissioned by Ruskin in 1855: he paid thirty guineas for it. The painting owes its inspiration to Dante’s dream in Purgatorio Canto 27:

A lady, young and beautiful, I dreamed,

Was passing o’er a lea; and, as she came,

Methought I saw her ever and anon

Bending to cull the flowers; and thus she sang:

�Know ye, whoever of my name would ask,

That I am Leah; for my brow to weave

A garland, these fair hands unwearied ply;

To please me at the crystal mirror, here

I decked me. But my sister Rachel, she

Before her glass abides the livelong day,

Her radiant eyes beholding, charmed no less

Than I with this delightful task. Her joy

In contemplation, as in labour mine.’

The two sisters, Rachel, the younger one on the left in the purple robe, and Leah, the elder sister in the green dress on the right of the well, were both wives of Jacob in the Biblical story. Dante stands discretely in the background on the left observing voyeuristically his dream in a Pre-Raphaelite setting. Ruskin extolled constantly the greatness of Dante — his landscape imagery in particular — and his writings are packed with textual and intertextual resonances. But he was critical of Rossetti’s interpretation and disliked the way in which Rachel (purported to be Siddal) sat, stiffly, by the fountain, and considered her face, which he found beautiful, to be spoiled by a “small underlip”, and the reflection in the water (Dante’s mirror) to be inaccurate. However, he appreciated the purple colour of the dress and the stonework and honeysuckle flower.8

Left: Elizabeth Siddal's Clerk Saunders. Right: Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Dante's Vision of Rachel and Leah

In Modern Painters, volume 3, which Ruskin was writing when he commissioned this painting, he challenged and refined the accepted interpretation of this vision as simply representing the active and contemplative life. He observed Leah and Rachel as follows: “Leah gathers the flowers to decorate herself, and delights in Her Own Labour. Rachel sits silent, contemplating herself, and delights in Her Own Image. These are the types of the Unglorified Active and Contemplative powers of Man”. Siddal’s Clerk Saunders (1857), (Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum) depicts a supernatural scene from Walter Scott’s eponymous love-ballad in the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, a work which Ruskin knew well (he was an avid reader of Scott’s prose and poetry). Margaret, in a pale blue gown, is gazing into the eyes of the ghost of her lover Clerk Saunders who has been murdered by her brothers.

From left to right: Mariana and The Order of Release by John Everett Millais; The Light of the

World by William Holman Hunt; and April Love by Arthur Hughes. [Click on thumbnails

for larger images and additional information.]

There were some striking examples of early Pre-Raphaelite work. Millais’s Mariana (1850-1) wearing a dress of sensually textured blue velvet, exuded sexuality as she leaned, longing for her lover to return. His The Order of Release (1852-3) suggested a double meaning in the title, Effie desiring release from the clutches of Ruskin. Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World (1851-3), with its web of Biblical allusions paralleled a larger version in St Paul’s Cathedral. Arthur Hughes’ April Love (1855-6), which would have been better placed next to Mariana, was, Ruskin wrote in his Academy Notes, “exquisite in every way; lovely in colour, most subtle in the quivering expression of the lips, and sweetness of the tender face, shaken, like a leaf by winds upon its dew, and hesitating back into peace” (CW 14: 68).

Pierre Edouard Frère (1819-86), the French genre painter, was one of the few contemporary foreign artists Ruskin discussed or of whom he approved, and The Evening Prayer (1857) was the only one represented in the exhibition. Although Ruskin recognised that it was “slight in work and poor in colour”, he appreciated “its very poverty and slightness [as] a part of its beauty” (CW 14: 142).

Ruskin was always a controversial critic, indeed he courted controversy, and over emphasised his idiosyncrasies for dramatic effect, both in his lectures and writings. In this respect he is perhaps best remembered for his vituperative attack, in a letter in Fors, on Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875) which was for sale at the Grosvenor Gallery in London for 200 guineas. He considered that “the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of wilful imposture”, and continued: “I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” (CW 29: 160). The well-known consequence was the libel trial, which resulted in a moral victory for Whistler and financial ruin, for he had been awarded the derisory sum of a farthing in damages and had to bear the costs of the trial himself. In reality, neither party won. Unfortunately the subject of the libel case was not on display, but had remained in Detroit. Other Nocturnes were at the Tate and provided a stark contrast to the realism, strong colours and moral teaching of the Pre-Raphaelites.

At the exhibition exit were Joseph-Edgar Boehm’s marble bust of Ruskin of 1881, and William Gershom Collingwood’s bearded portrait of the master aged 78, sitting in his favorite armchair at Brantwood. This was a poignant reminder of the importance of Collingwood in the life of Ruskin, neglected in the exhibition. It might be assumed that he was another painter, but he was more than that. Collingwood was Ruskin’s loyal amanuensis, his biographer, companion, admirer, translator of Xenophon’s Economist, and designer of the Celtic headstone for Ruskin’s grave in Coniston.

The aim of the exhibition was “to explore . . . Ruskin’s . . . modernity in his own time, and his modernity as someone who still has something to say, now” and “to present Ruskin as a contemporary critic” .9 To what extent did the organisers succeed? Ruskin was depicted as being very much aware of contemporary currents and he gave his support, for a limited time in certain instances, to many of the Pre-Raphaelites. His criticism of the sum of 200 guineas for the Whistler presaged his concern about art as a commodity and the burgeoning art market. He was such a powerful and influential critic, who had a fine grasp of language both spoken and written, with often whimsical views, that he could make or break an artist’s career at a stroke. After visiting the exhibition many times, the impression remained of Ruskin as a talented but unstable, rather dour character. The fun-loving, witty Ruskin was not apparent. However, the general public will surely have been made aware of Ruskin the artist and the range of his talent.

A superb catalogue, a book in its own right, the work of Hewison, Warrell and Wildman, provides a permanent record of the exhibition. Following Hewison’s essay “The Beautiful and the True”, the main structure of the book consists of ten chapters, each relating to one of the ten rooms in the exhibition. The chapter headings are:- 1, “Introduction”; 2, “Foundations”; 3, “Learning from Turner”; 4, “Venice and the Nature of Gothic”; 5, “Patron and Collector”; 6, “Ruskin’s Drawings 1844-1882”; 7, “Ruskin’s Pre-Raphaelitism”; 8, “A New Era of Art”; 9, “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century” and 10, “Conclusion”. Each chapter commences with an overview leading to an illustration in colour, where applicable, of each exhibit followed by an in-depth elucidation. That everything is viewed from Ruskin’s perspective (he is a voyeur in its original sense of “seer”) is underpinned by the quotations from his works or letters that accompany almost every painting. The quality of the colour reproductions, the text and the design of the catalogue is very high. The work is scholarly yet accessible to the general reader.

Last modified 6 May 2019