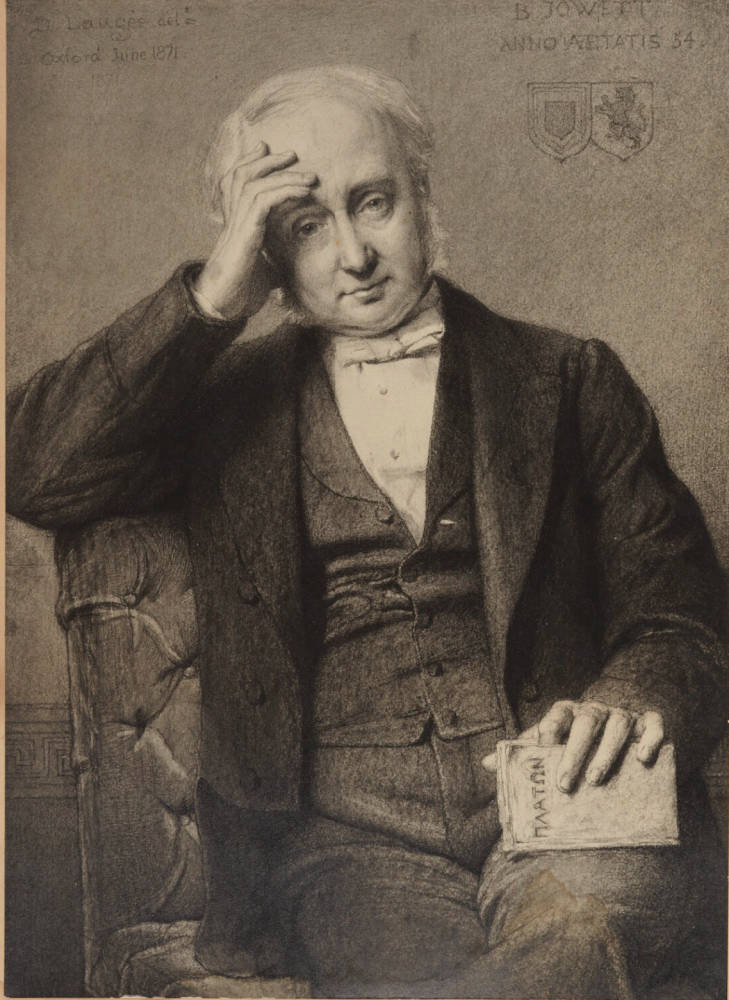

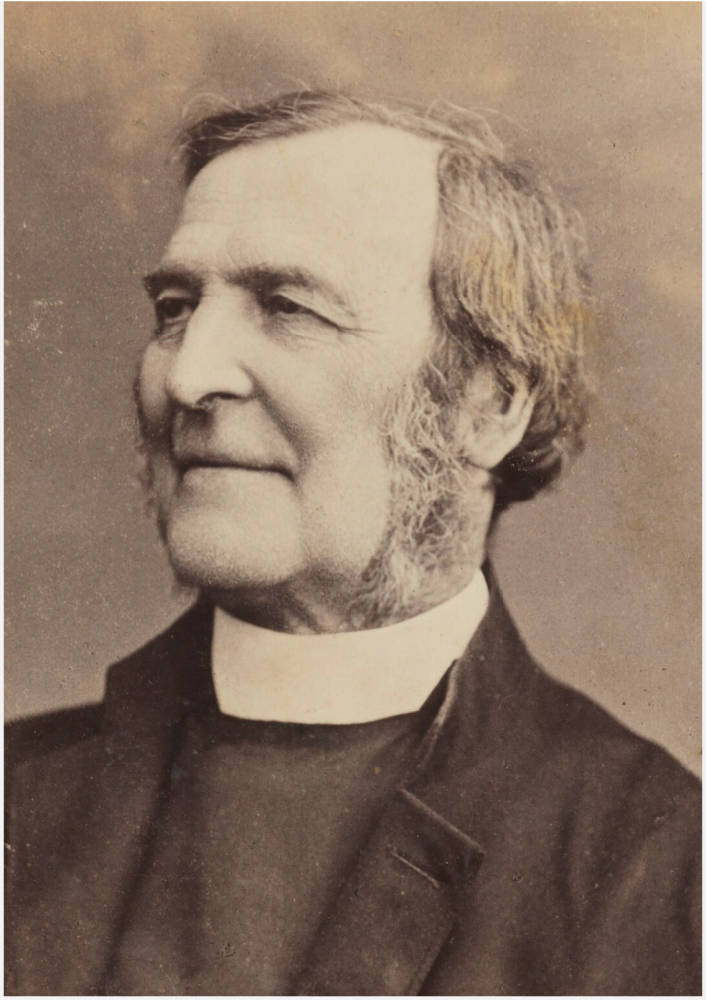

Left: Dean Liddell. Middle: Benjamin Jowett. Right: Frederick Temple. [Click on images to enlarge them and for more information about them.]

Oxford was in a ferment of odium theologicum, centred to some extent on the highly contentious Benjamin Jowett who, having failed to be elected Master of Balliol in 1854, had to wait until 1864 until his eventual election. In 1855, Jowett became Regius Professor of Greek; and, in 1860, he and Frederick Temple issued Essays & Reviews, a controversial series of essays, described by Roger Beckwith as "the historic manifesto of modern Liberal Anglicanism". This caused such a storm throughout Oxford and the Church of England that Jowett's enemies spent the next few years trying to deprive him of his salary as Professor of Greek. During these stormy times, Dean Liddell appears to have been mildly in sympathy with the biologist and advocate of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1805), and of a rational reading of biology and history.

At Christ Church, the arguments focussed particularly on the control of the College and the Cathedral. The disagreements and tension continued over many years, and are described in detail by E. G. W. Bill and J. F. A. Mason in Christ Church and Reform 1850-1867. Osborne Gordon found the new regime totally unacceptable, as he told W. E. Gladstone: "Our new Ordinance has cut off any prospect of permanent settlement here" (Bill and Mason 83). Gordon lamented leaving Christ Church, but his resignation in 1860 coincided with these virulent controversies which his tolerant and gentle nature would have found antipathetic (I am grateful to the late Malcolm Hardman for a discussion about this issue.). It cannot have been an entirely happy turn of events, for Gordon was through and through a Christ Church man, as Ruskin remarked: "His ambition was restricted to the walls of Christ Church" (35.251).

So, at the age of forty-seven, Gordon's life took a new direction, and he became rector of the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene, Easthampstead, Berkshire in 1860/1861, succeeding the Rev. Abraham Boyle Townsend. Although he appears to have been appointed in 1860, he did not leave Oxford until April 1861 to take up the Easthampstead living (Bill and Mason 83, 94-95). One of his last commitments in Oxford was probably a sermon he preached on Easter Day, 31 March 1861, in the Cathedral Church of Christ, based on Psalm VIII, 1: "O Lord our Governor, how excellent is Thy Name in all the World!"

It was not an unusual career change: Gordon's own headmaster Thomas Rowley at Bridgnorth School left to take the living at Willey Church where he died in November 1877, aged eighty years, "in the performance of his sacred office", as the inscription on a quatrefoiled plaque marking the spot indicates. Maureen Jones includes a photograph in Bridgnorth Grammar & Endowed Schools (14). Easthampstead, situated approximately half way between Oxford and London, proved to be the ideal place for Gordon. He enjoyed country life and would have been ill at ease in or near an industrial city in mid-or late-Victorian Britain. Gordon shunned the outskirts of London disfigured by slipshod houses and the railways. In one of his Oxford lectures as Slade Professor of Fine Art, "The Relation of Art to Use" (delivered on 3 March, 1870), Ruskin, deliberating on the need for quality dwellings and good town planning, invoked Gordon "an English clergyman" to support his argument:

Not many weeks ago an English clergyman, a master of this University, a man not given to sentiment, but of middle age, and great practical sense, told me, by accident, and wholly without reference to the subject now before us, that he never could enter London from his country parsonage but with closed eyes, lest the sight of the blocks of houses which the railroad intersected in the suburbs should unfit him, by the horror of it, for a day’s work (20.112-13).

The village and parish of Easthampstead included extensive woodlands – pines were prevalent – and heaths: some of the land was training terrain for officer cadets from the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, a few miles to the south. Also in the parish was Bracknell, which in 1860 Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Berks, Bucks, and Oxfordshire (25) described as nothing more than "a long village of one street, containing a graceful modern church of flint and chalk", a reference, most likely, to Holy Trinity Church. With the coming of the railway in the 1850s, Bracknell, on the Waterloo to Reading line, began to expand as a market town: from 1949 it developed rapidly, acquired a new identity as Bracknell New Town and eventually eclipsed Easthampstead. When Gordon arrived in Easthampstead, the population, according to Diane Collins, was "about 720": twenty years later it had increased to 888 (86).

In the first edition of Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Berks, Bucks, and Oxfordshire (1860), literary critic and travel writer Augustus John Cuthbert Hare (1834-1903), under cover of anonymity in the tradition of the series, had little to say about the church other than it had "a thick red-brick tower, and a fine old yew-tree in its churchyard" (p. 25). He was more interested in the monuments inside, not for their artistic qualities but as memorials to Sir William Trumbull and the poet Elija Fenton, both friends of Alexander Pope (1688-1744). No mention was made of the fine box pews that lined both sides of the central aisle.

The Rev. Osborne Gordon, who had obtained his BD in 1847, had gained a reputation for being a talented, eloquent preacher and speaker. At Easthampstead, he had his own fiefdom, away from university tensions, yet he remained in touch with his alma mater – for his church was a living within the jurisdiction of Christ Church.

The rectory

The rectory at Easthampstead commissioned by Osborne Gordon. W. R. Newson. 1950s. Watercolour. Private collection.

We do not know where Gordon lived in the very first few years of his incumbency, for the old rectory had been pulled down. He addressed this urgent problem immediately, and by 1863 he had achieved his goal. "I have built a house here –", he informed the Christ Church Censors, "and any number who will favour me with a visit will I hope be satisfied that it is suited to the Parish" (Collins 86). There appears to be no extant pictorial record of the house, designed by J. Hugall, save an amateur twentieth-century oil painting by W. R. Newson entitled and dated The Rectory 1950s. In the distance, the rectory, although indistinct, appears to have a red roof, gabled windows and a tall chimney. It was reached along a drive through established grounds with old trees that protected its privacy. Outhouses and sheds are positioned on both sides of the approach. This Victorian rectory, situated about a mile from the church, was demolished in the late 1950s. On the site a hexagonal seventeen-storey tower block of accommodation for single people or couples without children was constructed by Arup Associates in 1960-1964. It remains in the twenty-first century a prominent landmark visible from afar – one could think of it affectionately as "Gordon's tower". However, some of the old trees that Gordon and Ruskin would have known have been preserved and soften the effect of the reinforced concrete. An echo of the previous building is found in the address of the tower – Rectory Road. However, a most valuable source of information about the size and contents of the rectory is the sale catalogue of the contents after Gordon’s death. The batchelor rector was living in considerable comfort in a spacious rectory with servants. There were seven bedrooms, two dressing rooms, entrance hall, library, dining room, conservatory, WCs, principal staircase and landing, kitchen, pantry, larder, dairy, housemaid’s closet, servants’ hall, scullery, wash house, granary and stables. According to the 1883 Probate inventory (Ref. D/EZ118/2.) of Gordon’s estate in the Berkshire Record Office in Reading, his other home was Oak Cottage, Easthampstead.

A Restless Spirit

John Ruskin. Sir Hubert von Herkomer, R. A. 1879. Watercolour, 29 3/4 in. x 19 3/4 in. (755 mm x 503 mm). Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London (1336); Given by Sir Hubert von Herkomer, 1903.

Ruskin’s spirit was restless and disturbed. In an effort to separate himself physically and psychologically from the tyranny of his parents, he spent substantial periods of time abroad in 1862 and 1863: 15 May-12 November 1862; 15 December 1862-1 June 1863; 8 September-14 November 1863. He never really succeeded for, as James Spates has pointed out, Ruskin had a "negative" symbiotic relationship with them. Ruskin left London, without his parents, on 15 May 1862, primarily for Milan: however, in defiance of parental wishes, and unknown to them, he had invited Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones to accompany him as his guests. John James Ruskin was, as usual, paying all the bills. The simmering resentment and tension between father and son would increase crescendo-like, culminating in the Brezon débâcle and ultimately the death of John James Ruskin. It was a struggle to find just equilibrium and a modus vivendi between a dutiful son and a pater familias.

Research by Van Akin Burd and James L. Spates shows the extent of the tension and struggle and the degree to which the parents, instead of feeling proud, contrived to make their son feel guilty and insecure with their almost constant criticisms, nagging, and jealousy. When Ruskin preferred not to spend Christmas of 1862 with them – he chose to be in Mornez, in Savoy – John James, writing on 15 December, the very day of his son’s departure, emphasised the bleakness and their loneliness: "Mama was dull. I was dull – the house was very dull, the Servants were dull. The Candles were dull. The lamps burnt blue." This attempt at pathos and guilt induction did not have the desired effect. Ruskin remained abroad, for he had serious projects to address and bring to fruition.

Ruskin had already taken steps to secure plots of land near Chamonix, and near Mornex. The little isolated alpine village of Mornex, two or three miles south-east of Geneva, at the northern tip of the Salève mountain range, and close to the river Arve, was at the centre of Ruskin’s preoccupations. He discovered this beautiful spot in August 1862: it offered him the peace and tranquillity he needed, as well as being ideally situated for his geological studies. The mountain scenery was inspirational and breathtakingly beautiful. "The broad summit of the Salève lay, a league long", he wrote to his father in early January 1863, "in white ripples of drifted snow, just like the creaming foam from a steamer's wheels, stretched infinitely on the sea, and all the plain of Geneva showed through its gorges in gold: the winter grass, in sunshine, being nearly pure gold-colour when opposed to snow" (36.430).

As well as mountain walking and writing, Ruskin was busy sketching the winter foliage and bleak scenes. At least two of his works from this period were destined for the Gordon/Pritchard families – a juniper bough with leaves and berries, and a view from the Brezon. Ruskin despatched his "first juniper bough" to his father with precise instructions that it be framed by Richard Williams of Messrs Foord's on a "white mount about 2 inches or 2½ inches wide" and on "a light frame" (36.432). Ruskin's gift to Gordon, his View from the Base of the Brezon above Bonneville, Looking towards Geneva: the Jura in the Distance; Salève on the Left, was inherited by William Pritchard Gordon who lent the painting to E. T. Cook for reproduction in the Library Edition of The Works of John Ruskin.

View from the Base of the Brezon above Bonneville by John Ruskin. c. 1866. Graphite, ink, watercolour, and wash on white paper, 35.2 x 51.3 cm. Collection: Lancaster 1174.

Ruskin shaped the artistic taste of John and Jane Pritchard and Osborne Gordon through the kinds of paintings he generously gave them and the way in which he influenced some of their art purchases. At the Old Water Colour Society's Exhibition in 1861, it was Ruskin who advised Pritchard to purchase Paul Naftel's large watercolour of Paestum (which is now at Lancaster). According to James Dearden’s Ruskin, Bembridge and Brantwood other works that the Pritchard/Gordon families acquired were Ruskin's Walls of Lucerne, his Square at Cologne (1842) one of "the last drawings ever executed in my old manner" (35.316) , his fine watercolour The Valley of Chamouni (1844) in a Turnerian style, and Samuel Prout's Old Street in Lisieux (123-24).

Left: The Walls of Lucerne by John Ruskin. c. 1866.. Graphite, watercolour and bodycolour on blue paper, 34 x 48 cm. Right: Trees in a lane, perhaps at Ambleside . 1847. Collection: Both Lancaster 1376 and 1559. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

At this time, relations between Ruskin, his friends and John James Ruskin were becoming increasingly strained. Ruskin told his father: "you have cut me out with half my friends. The Richmonds – Dr. Brown – Bayne – Gordon – the Pritchards – think twice as much of you as they do of me" (36.436). No doubt that John James Ruskin's extremely generous gift to Gordon of £5000 as a personal tribute, without the need to justify the precise manner in which it was spent, would have contributed to a stronger bond between the two men but also to a degree of dependency. Since Ruskin was constantly asking his father for money that had to be justified and was sometimes refused, he may not have been entirely happy with his father's generous gift. In John James's account book for 1845-63, now at Lancaster, in his own hand, under the heading "Charities and Gifts 1862", can be found the following entry: "July 1st Rev. O. Gordon for poor livings Ch[rist] Church Oxford £5000." The money was given directly to Gordon in person rather than to the college authorities. When the munificent gift was presented, John James stressed Gordon's key role when he pronounced: "I give it to you, Mr Gordon, as Representative of the College, for the College" (Marshall 71). According to G.W. Kitchen, – Gordon’s successor as Censor at Christ Church and later Dean of Durham Cathedral – so completely did John James trust Gordon that in order to "express his gratitude for the good his John had got from Christ Church, he sent Gordon a cheque for £5000 to be given at the tutor's discretion for the augmentation of poor and needy parishes in the gift of the House". This was a huge sum of money, the approximate equivalent of £500,000 in 2020. To put this in perspective, in 1855 Charles Dodgson, as a master at Christ Church, received an annual salary of £300 (Carroll Diaries 135). It represented the esteem in which Gordon was held and the gratitude owed to him by John James Ruskin for his indispensable help and friendship to his son. John James’s account book records that he gave £2 to an unnamed Shropshire Church in November 1862 — a minute sum compared to his generosity to Christ Church livings.

1863-1864 Gordon's preoccupations at Easthampstead

Meanwhile, Gordon was preoccupied with practical problems at Easthampstead. Although A. N. Wilson extolled the delights of being a country clergyman in The Victorians, writing that "it is difficult for me to conceive of any more agreeable way of life than that of the Victorian country parson" (425), the move to village life was no sinecure. Gordon faced many challenges, one of the most serious being the church building itself. Neglected over many years, it was in need of repair and restoration. Previous bachelor rectors, Thomas Pettingal (in office 1783-1826) and Abraham Boyle Townsend (in office 1826-1860), had presided over a deteriorating, rundown rectory, outbuildings and church. In 1836 the parsonage was pulled down and not rebuilt. Townsend, renowned for his sharp tongue, had been largely unsuccessful in his attempts to persuade patrons to undertake maintenance and repairs. His relations with his neighbour and wealthy landowner, the fourth Marquis of Downshire, were at a low ebb, and there was considerable hostility between them. The Marquis had tried unsuccessfully to oust Townsend and buy the living (the advowson) from Christ Church. Townsend stood firm, but consequently he lost the confidence of his most powerful financial backer.

Murray’s description of Easthampstead in 1860 as "a pretty rural village" (25) belied the undercurrent of tension into which Gordon was plunged. All his charm, sensitivity, diplomacy and common sense were needed to diffuse the situation. This he did, and achieved results beyond any expectations. His major task was that of a fund-raiser: his parish church was falling down and there was no rectory. In 1863, he alerted his Christ Church patrons to the extent of the problem: "The church is of the worst character. I have had it surveyed and estimate sent in for its enlargement & repair which is virtually rebuilding it at a cost of £3000" (Collins 24). This equates to approximately £300,000-£400,000 in 2020. John James Ruskin’s gift of £5000 to Gordon would easily have paid for the rebuilding, but it seems to have been designated for the poor.

Gordon was concerned about the poverty of his parishioners, their increasing numbers, and the lack of a proper school and facilities. He explained the situation to the Christ Church Censors in a letter of 1 May 1863:

The population is about 720 and likely to increase. I think all the people are well disposed and there is nothing like organized dissent if there are dissenters in the place, but the parish is very badly supplied with everything that a parish requires for its well being. There is no school & I have hitherto failed in establishing one – though if established it would be supported at little or no cost to the clergyman. There are two dames schools and I get about 40 children together on a Sunday and I have had an evening school attended by an average of 20 during the winter months. This is the only provision for education in the Parish. [Collins 86]

William Edward Forster (1818-1886). 1880 Courtesy of The National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG x13999 Acquired Harrison Collection, 1952

It was not until 1870 that the Elementary Education Act was passed, mainly due to the work and drive of William Edward Forster (1818-1886), Liberal MP for Bradford who rose to cabinet rank and was placed in charge of education in Gladstone’s first period of office as Prime Minister (1868-1874). The Act instituted a State system of compulsory, basic education: Forster argued that since householders had been given political power – the right to vote since 1867– they needed to be educated in order to exercise that right. There was much debate about the compulsory nature of the Act and the right to freedom. Ruskin, of course, had strong views. He favoured the acquisition of manual skills, an apprenticeship system in which "wholesome and useful work" was the first condition of education (27.39). He challenged and questioned the meaning of the word "education" as used by Forster and initiated a debate, via his public letters published monthly as Fors Clavigera, on the curriculum and what skills and knowledge were needed to produce good, useful, contented citizens who had satisfying jobs (27.60-64). Ruskin opposed compelling children to undergo the kind of "education" Forster proposed that was totally at odds with his own views. As late as 1886 Ruskin was still vehemently opposing Forster’s bill as a kind of theft and angrily wrote a letter to the Pall Mall Gazette: "I do extremely object to Mr Forster’s breaking in to my own Irish servant’s house, robbing him of thirteen pence weekly out of his poor wages, and, besides, carrying off his four children for slaves half the day to play tunes on Wandering Willie’s fiddle, instead of being about their father’s business" (34.597).

Although Gordon supported the general principles of the 1870 Education Bill, he was opposed to a system that only allowed a modicum of religious instruction, by which he meant the Established Church: he believed that the State had a duty to include that subject. In this, Ruskin agreed with him in so far as a child should be taught a "religious faith" (29.250). Gordon made repeated references to the importance of religious education in his sermons, one of which, entitled "The Great Commandment and Education", was published in 1870 (Marshall 44). In it, he warned his rural congregation of the danger of "a design for covering the whole land with a system of schools, from which religious teaching shall be entirely excluded".

Not only did Gordon have responsibility for the church and Sunday school, but also for some ninety-three acres (approximately thirty-eight hectares) of glebe, the land granted to a clergyman as part of his benefice. A competent farmer and manager, Gordon improved the wild, neglected glebe so skilfully that it "was before long", Marshall reported, "in a state of high cultivation" (Marshall 43). Stressing his success to his Christ Church patrons, Gordon wrote: "the Rectorial farm of 93 acres when I took it was fast going out of cultivation but I have reclaimed it, and in another year or two it will be in good order" (Collins 86-87). He added confidently: "I think it will prove a very excellent tithe farm and should I at any time wish to give it up I have no doubt it would fetch a much higher rent than it did when I took to it." So renowned a farmer did he become that he "soon became quoted as an authority on agricultural matters" (Marshall 43). His agricultural projects were far more successful than Ruskin’s experiments! The entrepreneurial Gordon worked immensely hard and directed his energies to making the glebe profitable and fruitful, and a source of income for Christ Church. In a letter of 1 May 1863 he gave financial details to his patrons in his account of his living:

The gross value on an average of the last three years I have returned to the bishop of Oxford at £653 15 0 including glebe at an estimated rent of £97/a. the net value I have returned at £506 5 5 but this does not include fees which are insignificant, the tithe is commuted at £516 – I think – but this includes the tithe on the glebe which I have the pleasure of paying myself with greater punctuality than I am able to enforce on the rest of the tithe payers. [Collins 86]

Gordon, highly respected for his agricultural knowledge and competence, enjoyed his not incompatible role of farmer and priest. An article in the Reading Mercury, Oxford Gazette, Newbury Herald, and Berkshire County Paper for 3 October 1863 reported his speech at the dinner of the Royal Forest Agricultural Asssociation, held at the Hind’s Head Inn, Bracknell, in which he pointed out "a great resemblance in the work of moral cultivation, and the cultivation of the soil" and that there was "a great deal of work to be done, and there were a great many weeds […] to be got out of the human heart". He was cheered when he said that the "human heart was to be cultivated in the same way as the soil, and [that] he who was called to cultivate the two, occupied a position which might well be envied" (6).

There was a shortage of good labourers and Gordon’s solution, at least to his own immediate problem, was to provide accommodation for them. By this means, he could attract, and keep under his supervision, the quality staff he required. He sought permission from his patrons to borrow £200 in order to build the tied cottages (Collins 15). Here is the letter of 26 August, but of uncertain year, that he wrote:

Dear Sir

I do not know which of the Canons may be in residence now so I write to you. I wish to borrow £200 from Queen Anne’s Bounty for building one or more cottages on the glebe. At present there is not one and it is consequently impossible to obtain good labourers. The approval of the Chapter is required for this and I hope there will be no obligation as I have hitherto laid no charge on the living and spent large sums upon it – I should wish to begin at once but fear I shall have to wait for a chapter – will you have the kindness to show this to the resident canon and believe me

Sincerely yours, O. Gordon [Collins 87]

In contrast to the poor dwellings of the villagers stood the Downshire family country house of Easthampstead Park, a large mansion set in over sixty acres of parkland. Easthampstead Park had many royal and historical connections: Richard III had a hunting lodge in the Park; Queen Catherine of Aragon, the estranged wife of Henry VIII, stayed there in 1531; James I resided there in 1622 and 1628. Like the little parish church, over the centuries it had suffered from neglect and had become dilapidated. This fine building, apart from the stable block, was demolished in 1860, and work commenced on a new mansion almost immediately. So demolition and rebuilding were already ongoing when Gordon arrived – another reason why there was a shortage of workmen for the glebe – and his decision to act similarly as regards his church may have been influenced by these works and prevailing ethos. The idea of preserving and repairing these monuments was not considered. In later years, the new Easthampstead Park was described as a "building of historic and architectural interest, in Jacobean style with curved gables, pierced stone parapet and stone frontispiece of naïve classicism" (Collins 49).

Hair-brain schemes in the Alps: Osborne Gordon to the rescue

Ruskin wanted to settle in Savoy, and planned to build a house for himself among the mountains: he even investigated purchasing an entire mountain. He eventually decided to build his chalet on the Brezon (also spelt Brison, Brizon, Breson), south of Bonneville. The land he chose was isolated and bleak. But Ruskin seemed totally committed to a foolhardy project, almost an escape from his father to whom he wrote, from Mornex:

I mean to have the summit with two or three acres round it, and the cliff below: this is all barren rock, and should cost almost nothing – there is only a little goat browsing on it in summer […]. But from the flank of it slopes down a pasturage to the south; the ridge of which is entirely secure from avalanche or falling rocks, and from the north wind: it looks south and west – over one of the grandest ranges of jagged blue mountain I know in Savoy. It is accessible on that side only by a footpath, but the summit is accessible to within a quarter of an hour of the top, by a bridle path (leaving only a quarter of an hour’s walk for any indolent friend who won’t come up but on horseback). It is about 5000 feet above the sea. [36.444-45]

As regards the proposed dwelling, Ruskin continued: "I think it would be foolish to build a mere wooden châlet in which I should be afraid of fire – especially as I should often want large fires. I mean to build a small stone house, which will keep anything I want to keep there in perfect safety, and will not give one the idea of likelihood to be blown away" (36.444).

Ruskin had taken the project further by formalising it: he arranged for the Mayor of Bonneville (Bonneville local council owned the site) and the Mayor’s lawyer to go up the Brezon to be shown the land, then for a surveyor to prepare a plan and for an offer to be made to purchase it. One can imagine the chill that went through his father’s veins on receipt of this information. John James would have been even more anxious on learning a few days later that his son had impetuously bought, beneath the Aiguille de Blaitière, in a rugged area south-east of Chamonix close to the Glacier de Blaitière, some "splendid rock and wood, the space of ground being altogether about 100 times as large as the village of Chamouni", for the sum of "£720 (18,000 francs)" (36.445).

Ruskin returned to the parental home at Denmark Hill on 1 June (1863). John James Ruskin reflected on how best to cope with his headstrong son’s projects, for his own powers of persuasion were ineffectual. So he decided on a strategy of harnessing the help of friends likely to exert some influence and make Ruskin change his mind. Foremost among these was Gordon, renowned for his cool, common sense, and a man greatly respected by John James. Georgiana Burne-Jones was also one of the concerned friends and had written to John James expressing her worries about the scheme. In his reply to Georgiana, he reveals his anxiety and his hopes that Gordon will be able to exert some sound influence, indeed he suggests that he is the only person capable of this:

I am happy to think of my Son possessing so much of your and Mr Jones’ regard, and to hear of so many excellent people desiring to keep him at home; […] my hopes are, that my Son may ultimately settle in England; but these hopes would not be strengthened by his too suddenly changing his mind, throwing up his Engagements, breaking his Appointments, or at all acting on the whim of the moment. He so far proceeded towards a settlement in Savoy as to have begun treating with a Commune about a purchase of Land. His duty is, therefore, to go to Savoy and honourably withdraw from the Affair, by paying for all Trouble occasioned, and I fully expect the Savoyards will afford him some ground for declining a purchase by the exorbitant prices they will ask for their Land. As for the ground he has bought at Chamouni, it will be a pleasure to him to keep it though he saw it not once in seven years. It is the Building Plan near Bonneville that I should rejoice to see resigned […]. He has made a short engagement to go to Switzerland with the Rev. Osborne Gordon, which I hope he will keep, and I shall endeavour to hope that his Engagements abroad may in future be confined to a Tour with a friend, and that Home Influences may in the end prevail […]. My Son’s fellow Traveller now is the best he could possibly go with. Being rather cynical in his views generally, and not over enthusiastic upon Alps, he is not likely to much approve of the middle heights of the Brezon for a Building Site [17.lxxiv-lxxv]

Towards the end of this three-month summer interlude in England in 1863, Ruskin spent a few days in Cheshire. His destination was Winnington Hall, a girls' boarding school near Northwich, run by Miss Margaret Alexis Bell. He enjoyed participating in the life of the school, and directing the students in areas of dance, art and music. In spite of Ruskin's professed dislike of children – by which he really meant babies and infants – he was in many ways a born teacher but liked to dictate his own curriculum according to his beliefs, at the centre of which was art education or the education of the eye. But even in the relaxed environment of Winnington, Ruskin was preoccupied with the purchase of land and property in Savoy, as his daily letters to his father testify. At times he tries to reassure his father that he is behaving in a responsible and business-like manner and consulting with sound friends (of whom Gordon): "I shall examine the ground well with Dr Gosse, Coutet, Gordon & perhaps Henry Acland, and fix my price, and require an answer in a week at most – yes or no, I don't care which. I can find plenty other places" (Winnington Letters 416-17). Ruskin also discussed the purchase with Headmistress Miss Bell, who opposed the plan. He could not stay at Winnington as long as he would have liked as he had fixed a date with Gordon for their departure for Mornex. That could not be changed, for Gordon did not have the flexibility to alter his schedule owing to the requirements of his regular priestly duties at Easthampstead.

So the country parson and the famous writer, walking companions, intellectual companions and true friends, travelled together through France, leaving England on Tuesday 8 September 1863. They breakfasted with the Richmonds at Boulogne on the Wednesday morning and left that same day at 12.20, arriving at Bonneville at six o’clock the next day (Diaries, II, 581). Nothing but the Brezon occupied Ruskin’s mind: "Red light comes out on Brezon crags", was his diary entry of 10 September (Diaries, II, 581). "Up Brezon", was his only entry on Friday 11 September. Five days were then spent in Chamonix, from Saturday 12 until Wednesday 16 September, the day that Gordon left (Diaries, II, 581).

On the first working day of their Chamonix stay, Monday 14 September, and immediately after breakfast, Ruskin "sent for the notary and Couttet to take counsel with". The plan was to formalise as quickly as possible the purchase of a plot of land near Chamonix. They "got the act drawn up in form": it was, Ruskin continued to inform his father, "very simple and unmistakable" (36.453). Couttet had made enquiries during Ruskin’s absence in England relating to the titles of the property, "and f[ound] them all right". Couttet, a local guide descended from a long line of Chamonix guides, had excellent knowledge of Mont Blanc and the Alps, but how competent was he to do the property and land search and come to the conclusion that the titles were "all right"? This was an example of misplaced confidence by Ruskin and another foolhardy act. Then Ruskin proceeded to inform his father about extra costs in the form of a purchase tax: "There is a Government duty on purchases of land which is either 6 or 6 ½ per cent., which will add £50 nearly to the price. But, on the other hand, being proprietor in the Valley gives me the right to a share of all the common pasture and wood, which is much more than £50 worth." This information was followed immediately by a request for money, the substantial sum of £1000: "You had better now send me a credit to Geneva for £1000 – the odd £200 I shall want for travelling, for Allen, etc." (36.453). Ruskin also conveyed to his father the strong impression that Gordon, in whom John James Ruskin had so much confidence, supported the scheme: "Gordon likes the look of this place very much – nobody seems to approve of the Brezon" (36.453).

Gordon did indeed exert the beneficial influence so desired by Ruskin’s father, and dissuaded him from embarking on the Brezon "Building Plan". Gordon broached the delicate subject with his stubborn, determined friend in a pragmatic way: they both walked up the Brezon and there they discussed the practicality, or rather impracticality, of the scheme. From a height of several thousand feet, "a waste of barren rock, with pasturage only for a few goats in the summer" (35.436), the sheer folly of the plan was obvious as Ruskin conceded: "Osborne Gordon […] also walked up with me to my proposed hermitage, and, with his usual sagacity, calculated the daily expense of getting anything to eat, up those 4000 feet from the plain" (35.436). Water too would have to be carried up the mountain. Gordon used convincing arguments, highlighting Ruskin’s isolation and how deterred his friends would be from visiting. "If you ask your friends to dinner, it will be a nice walk home for them, at night", Gordon remarked with sarcasm (17.lxxv). In response to Ruskin’s anxiety that unexpected visitors might arrive at the isolated chalet and, finding no-one at home, might not come again, Gordon added simply, "and I don’t think they would come again anyhow" (17.lxxv). Ruskin stayed on in the Alps and reflected.

The day after Gordon left, and soon after receiving John James's letter "with various objections to the Brezon", Ruskin wrote to his father on 17 September 1863, from Chamonix, that the "wisdom of Gordon" was one of the reasons – others included "the persuasion of Winnington […] and affectionate sense of John Simon and chiefly, your & my mothers wishes" – why he was considering withdrawing from "the Brezon business" (Winnington Letters 432). Ruskin was probably trying to save face, for Chris Pool's more recent research has revealed that at the Bonneville Council meeting of 23 August 1863, councillors placed restrictions on the plot on the Brezon, fearing that Ruskin had plans to implement some of his socio-political projects – "an outworking of his social thinking" (56) – among the local people, with the danger of encouraging tourism and blighting the area. The councillors were right, for Ruskin did indeed have other plans and motives, including the wish to purchase the entire mountain! On hearing the outcome of the Council meeting, Ruskin abandoned the scheme. However, Ruskin understood that his negotiations about the plot of land at Chamonix had reached a point of no return, and that he must pay for the land as promised.

On his way back to Easthampstead, Gordon called in to see Ruskin's parents and report on the Brezon affair and the "Savoy news". He was due at Denmark Hill on 22 September. Ruskin had enclosed a note for him in a letter to his father. This was a happy and reassuring occasion for the Ruskins and the success and influence of Gordon a cause for celebration with the best wines and spirits brought up from John James's cellar. Ruskin, in Chamonix, sensed the sparkling scene and advised his father about Gordon's tastes in wine: "I have very improperly and wickedly forgotten to give you warning in time that he doesn't like champagne – drinks it merely out of compliment, when it is drawn. He enjoys his claret – but I have no doubt he will have courage to say so himself on the occasion of his bringing you his Savoy news" (Winnington Letters 433-34).

But on the very day of the celebration with Gordon at Denmark Hill, Ruskin had further doubts and thought he "may have to pay something for Brezon". This was followed by an urgent request, to his father, for £500 or rather £774 to be transferred to a Geneva bank by 1 October at the latest. A diary entry by John James Ruskin on 26 September 1863 appears to be a summary of a letter from his son about these events: "Miss Bells letter led to further reflection – In case of illness – no Dr nor surgeon – Delicate no stamina … Jones ill of cold now I like Chamouni & Mornex only for the pilgrimage in June & July – agrees with Gordon – impossible & unpracticable to build – unwise to throw away money –" (Winnington Letters 433n).

After peregrinations into Germany (Baden), Switzerland (Schaffhausen, Basle) Ruskin eventually returned, via Paris and Abbeville, to England on 14 November 1863. He was struggling to be independent, to own his own property and home for the first time. But he was thwarted and stifled by his father. Not surprisingly, simmering resentment built up and angry words of indictment were expressed to his parents. John James Ruskin controlled the purse and consequently controlled his son. It was an angry and embittered son who unleashed his pent-up feelings in a letter of 16 December 1863 to his father. He accused his parents of treating him so effeminately and luxuriously that he had been rendered incapable of travelling "in rough countries without taking a cook with [him]". But the most cutting criticism followed: "you thwarted me in all the earnest fire of passion and life" (36.461). It was hardly appropriate for the seventy-eight-year-old patriarch to be canvassing support (from Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones and others) behind the back of his forty-four-year-old son.

Parental pressure was becoming more and more unbearable and by New Year 1864 Ruskin had abandoned his Savoy plans. This had made him feel "unsettled and vexed" and very uncertain of his future (36.462). John James Ruskin had undermined his son's authority.

John James Ruskin died a few months later on 3 March 1864, ten weeks before his seventy-ninth birthday. John Pritchard, and John Champley Rutter, a senior partner in the law firm of that name, ("a gentleman" (27.281, note)) were his trusted executors for his will. In some ways, Pritchard had had greater affinity with John James: both were born in the late eighteenth century and there was only eleven years’ difference in their ages.

Last modified 10 March 2020