he exercise of imaginative perception does not exhaust the experience of visual art for Ruskin. The perceptual process I have compared to romantic reading Ruskin refers to simply as "seeing," "seeing and feeling," or "perception." But aspects of both real landscapes and paintings or buildings began by the early fifties to elicit from him a further mental activity, which he called "reading." This kind of reading is not the perception of light and color as figure and space or even the comprehension of it, in a given composition, as "mental expression." That comprehension is an inseparable part of the perceptual process of imaginative sight, by Ruskin's definition. "The Nature of Gothic" deals with the Gothic as an object of perception, discussing material form and mental expression or mental character; but at the end of the chapter the spectator is enjoined to look for something more. We must also "Read the sculpture."

In The Stones of Venice the text read by the spectator is, in most cases, a particular iconography common to much medieval and early Renaissance art and literature, with both scriptural and classical sources. We pass from perceiving to reading when we encounter an explicit symbolic language employed by artist, sculptor, poet, or workman, "that great symbolic language of past ages, which has now so long been unspoken" (11.205). Reading, as Ruskin exemplifies it in Stones, is the interpretation of figures whose probable meaning is arrived at through comparison with related figures in other texts or works of art and reference to nature and to relevant scriptural passages. It is clear that such reading can contribute to the perception of mental expression, but that perception does not depend on reading. Ruskin makes reading a subordinate part of the total visual activity of [201/202] exploring a building.1 He repeatedly insists that a good building must make aesthetic sense at any distance; this is the corollary to the assumption that a spectator will shift perspective and move around, up to, and through a work of art—a movement of the eyes only, in the case of a painting, but of the whole body in the case of buildings or actual landscapes. The iconography of a building will not of course be readable at all distances. It is, then, no part of much of the visual experience of architecture.

Yet Ruskin does give increasing importance to the interpretation of figure or icon, beginning with Stones of Venice. Why does he become interested in adding reading to seeing at this time? How does he reconcile this new stress on interpretation with his earlier approach to Turner? His two models for reading the language of art are not at first glance compatible. As Ruskin readers well know, the interpretation of visual iconography, however justified by the work of art in question (and it usually is), can be weighed down with a burden of significance disproportionate to the role it plays in the spectator's response. That significance is often indicated in language that is not psychological or aesthetic but religious. Iconography acquires its special importance through its resemblance to or coincidence with symbolic language of quite a different nature—the Real or divine language of the Bible and of a significant universe. So much verbal emphasis does Ruskin give to the religious reading of symbolic languages that the role of his ideas on perception has often been lost sight of. Moreover, the shift from a psychological to a religious terminology to describe the reading of symbolic language in art has made it difficult for modern readers to see what common ground might exist between these two aspects of Ruskin's response to art. Ruskin devoted a good part of Modern Painters IV and V to an elaborate attempt, through an argument from metaphor, to reconcile religious reading with the romantic reading of Turner he had advocated in Modern Painters I. Without, I hope, minimizing the philosophical difficulties posed by Ruskin's yoking two different conceptions of language, I would like to reexamine his use of scriptural exegesis as a model for reading art.

lthough Ruskin was thoroughly familiar with figural interpretation from his religious training when he began Modern Painters, there [202/203] is no real place for symbolic language or explicit "reading" in the first two volumes. (He uses typological allusions in his descriptions of paintings or landscapes, but does not instruct his readers to do so.) In part the exclusion was planned: Ruskin from the first intended to treat "ideas of relation" in a later volume. But his study of Gothic architecture in the late 1840s and early 1850s seems also to have changed his attitude toward the role of reading in the perception of visual art. He changes his mind about the extent to which the ordinary spectator can read the symbolism of art, and he formulates for himself a critical identity to which reading is central.

Ruskin's interest in the use of symbolic languages in art develops together with his conviction that all visual perception must be active and imaginative. When he calls art a language at the beginning of Modern Painters I he presents it as a language of painted line and color, signifying the visual aspect of things while expressing mental process. The notion of language, however, is chiefly useful as a way of stressing the second, expressive function of visual art. Ruskin's own descriptions in Modern Painters I may suggest that visual language requires a great deal of active seeing on any spectator's part, but as we have already seen, when he discusses the effect of paintings on spectators he does not stress this activity. The response of the ordinary spectator is limited to perceiving painted line and color as natural objects, which, Ruskin implies, is not commonly felt to be very demanding. Expressive or imaginative art does involve spectators in the "active exertion of the intellectual powers" at the instant of perception (3.115). But this kind of active seeing is limited in Modern Painters I to the very few, to "minds in some degree high and solitary themselves" (3.136). It seems to be a form of poetic or artistic activity and not a part of the ordinary perception of aesthetic objects. Only for the small and privileged group of active seers does art function as a language to express mental process. The ordinary spectator, Ruskin implies, will be conscious of art simply as faithful representation, not as a system of signs.

The situation is not much different in Modern Painters II. There too Ruskin seems to conceive of sight as separable into a hierarchy of perptive responses: the merely sensory, the emotional-sensory ("moral" or "theoretic" perception), and the intellectual. Only intellectual perption is an active exertion of the mind, but this exertion is a usually quite unnecessary, at most very minor part of the effect of beauty on [203/204] the spectator. The volume is divided into a discussion of the two faculties concerned with beauty, the theoretic and the imaginative. Imagination, "the highest intellectual power of man" (4.251), is always described as active; in it the mind is exercised in combining, regarding, or penetrating (4.36,228). The extended description of imagination in Modern Painters II, probably based on Wordsworth's supplementary essay of 1815, develops a concept of active thinking-as-seeing very close to the imaginative perception of Modern Painters III — but ascribed, in the earlier volume, to artists and poets only. The theoretic perception of the normal spectator is, by contrast, more or less passive sight; it is instinctive feeling (joy, love, and gratitude) aroused by beauty (4.47-49,211). Here, as in Modern Painters I, Ruskin deemphasizes the symbolic character of aesthetic objects insofar as that might imply that aesthetic perception is intellectual. When he is talking about imagination in the artist, however, he readily admits the symbolic function of visual imagery in art. Just as every word of an imaginative poet carries "an awful under-current of meaning" (4.252), so even the naturalisticallv painted objects in a Tintoretto are put to "symbolical use" (4.269). Ruskin is here, as in Modern Painters I, very cautious about symbolic modes of representation (exaggeration, abstraction, reduction to simplified character), but he wholly accepts symbolical use or intent as a sure sign of a powerful imagination (4.297-313,261-78).

The ideas of natural beauty to which the theoretic faculty responds, however, though many of them are in fact symbolic, do not constitute a "language" or—with one exception—elicit interpretation. Formal qualities that appear beautiful (varied curvature, bright horizons) do signify, typify, or suggest divine attributes, Ruskin maintains, but this moral meaning is "only discoverable by reflection" that plays no part in the instinctive emotional response of the spectator (4.211). Ideas of vital beauty (complementing those of typical beauty) are for the most part not symbolic at all; "the felicity of living things" and their "perfect fulfilment of their duties and functions" are directly perceived by the theoretic faculty (4.210). Sympathy, or sympathy plus some natural history, is sufficient. There is one respect in which ideas ot vital beauty do function as language, or at least seem to require interpretation: images of living things can serve as "the record of conscience, written in things external" (4.210) or as a lesson that must be rightly read (4.147). Except for this one aspect of vital beauty, however [204/205] (and Ruskin does not spend much time discussing it in Modern Painters III, response to beauty does not require active or intellectual perception; nor is the notion of art as symbolic language relevant to the kind of spectator response that Ruskin is concerned to establish.

But this treatment of aesthetic response is incomplete, as Ruskin himself admits. The theoretic faculty responds to natural beauty and to art insofar as it represents that beauty faithfully. The imaginative faculty of artist or poet works on natural beauty (or rather on the visual aspects of natural objects) and gives it expressive or symbolic significance. What is the spectator's response to imaginative art? Here, as in Modern Painters I, Ruskin gives two answers: the implied example of his own perceptions, this time in the interpretive descriptions of Tintoretto's paintings, and a brief explicit discussion of a privileged spectator. The Tintoretto descriptions exhibit the same visual exploration and verbal energy of the Turner descriptions in Modern Painters I, joined with an increased attention to deliberate allusion and symbolic intention. For the Annunciation in the Scuola di San Rocco, for example (4.264-65), Ruskin begins by focusing on the setting—a ruined palace—insisting on the almost grotesque detail of "the central object of the picture ... a mass of shattered brickwork, with the plaster mildewed away from it, and the mortar mouldering from its seams." Carefully leading the spectator from that unlovely object along "a narrow line of light" connecting the brickwork with discarded carpenter's tools beneath it—a crucial compositional line—Ruskin finally identifies the symbolic significance of those elements that the spectator, guided by visual elaboration and composition, has been led to explore. 'The ruined house is the Jewish dispensation; that obscurely arising in the dawning of the sky is the Christian; but the corner-stone of the old building remains, though the builders' tools lie idle beside it, and the tone which the builders refused is become the Headstone of the Corner." As in the earlier volume, the progressive unfolding of imagery and meaning here implies that both are accessible to Ruskin's spectators, if they will only look more carefully.

The Scuola san Rocco, Venice. The Annunciation by Tintoretto. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

Ruskin must acknowledge that this kind of looking requires something more than the instinctive theoretic response. He does acknowledge it, but when he does so he again suggests that this more active, intellectual response, and hence the whole range of imaginative symbolism to which it gives access, will be possible only for a very few [205/206] spectators. However, in Modern Painters II for the first time Ruskin describes this privileged spectator not only as establishing a sympathetic identity with the mind of the artist, but also as participating in a process of imaginative perception which can, to some extent, be learned. "Imagination addresses itself to Imagination," but the imagination of the spectator now seems to Ruskin perhaps "less a peculiar gift, like that of the original seizing [by the artist], than a faculty dependent on attention and improvable by cultivation" (4.261).

As so often in Ruskin's work, the first signs of a shift in emphasis or direction appear in a volume whose major argument runs along quite different lines. The boundary between passive emotional perception and active imaginative perception is increasingly eroded in Ruskin's subsequent volumes on architecture, Seven Lamps and The Stones of Venice, until, by Modern Painters III, it has become virtually impossible to separate the two kinds of response. Nearly forty years later, revising Modern Painters II, Ruskin firmly stated the position toward which he had, in 1846, just begun to move. "The 'Imagination' spoken of is meant only to include the healthy, voluntary, and necessary action of the highest powers of the human mind," he noted—and still later he would gloss that note as meaning "that all healthy minds possess imagination, and use it at will, under fixed laws of truthful perception and memory" (4.222). The spectator's viewing is not, then, passive feeling, but active imaginative perception, as Ruskin asserted in Modern Painters III. What one might call the democratization of imaginative perception leads to Ruskin's growing conviction that perception is a matter not just of individual but of cultural health, that it can vary historically and that it can be directly related to changing social and economic conditions. The new emphasis on active seeing is also accompanied by increasing attention to art and language, particularly to art employing a variety of symbolic languages that convey meanings requiring interpretation. Reading, whether of art or of literature, becomes an explicit concern in Ruskin's criticism when he acknowledges that an intelligent response to art is not a gift but an activity that can be learned. The model for aesthetic experience is not the poet's sublime encounter but the tourist's or reader's excursive exploration.

What Ruskin sometimes saw as his long detour from landscape painting into architecture had clearly a great deal to do with that changes in his ideas of aesthetic experience between the mid-forties an [206/207] the mid-fifties. We have already seen some of the ways in which the study of architecture reshaped his criticism: the connections between architectural experience and the excursive habits of garden visitors and travelers, the associations between Gothic buildings and the picturesque, the use of travel as an approach to history and to the development of an historical self-consciousness. I want to look briefly now at two other aspects of Ruskin's architectural criticism: his recognition of the spectator's necessary activity in examining a building, and his interest in sculptural iconography addressed to the general spectator. Both concerns are already evident in Seven Lamps and begin to affect his attitudes toward the viewing of all art in The Stones of Venice.

In Ruskin's chapter on sublime architectural effects in Seven Lamps (text of chapter), the spectator's focus shifts from distant to near in the course of the chapter. Ruskin tends to adopt, by preference, an excursive rather than a sublime approach, to get at the whole through a study of its parts. In the first volume of Stones this shift in focus is explained differently. There Ruskin recognizes change in position and shift in focus as a necessary part of the viewing experience, concluding that one criterion of excellence in architecture must therefore be that it continue to make aesthetic sense, on some level, whether one looks at it from a great distance, a middle distance, or at very close range.2This description again postulates a kind of hierarchy of perception—sculptural programs and expressive handling become increasingly intelligible as one approaches a building—but here the hierarchy is a function of changes in the circumstances of viewing, not of the presence or absence of imagination or a high and sympathetic mind in the viewer.

At the same time, Ruskin begins to consider the language of architecture not as language for the few but as historical record or moral instruction for the many. Seven Lamps stresses the memorial function of architecture, to be achieved both directly through a usually symbolic sculpture and indirectly through the accidental age marks of the significant picturesque. Through sculptural iconography and through the picturesque, architecture is a record addressed to everyone (8.229-37). The implication that architecture uses languages everyone can read becomes explicit in Stones: Ruskin's first references of 'symbolic language" in art which must be read occur in a book concerned with reforming the perceptions of ordinary tourists. The outstanding example of architectural language in Venice, according to [207/208] Ruskin, is the mosaics of St. Mark's—intended as a pictorial Bible for the illiterate (10.129-30). The modern tourist, like the medieval Venetian populace, can and should read the symbolic language of mosaic or sculpture. Reading architecture has become one part of the activity of looking at it. Reading no longer requires the exercise of rare gifts by the spectator.

St. Mark's, Venice and one of its mosaics. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

But the artist in Stones is, after all, a common workman. Can the democratized response to visual language be extended from architecture to painting? At the end of Stones Ruskin thinks not. Tracing the rise of the English school of landscape to "a healthy effort to fill the void which the destruction of Gothic architecture has left," Ruskin finds painting less accessible to the spectator:

The void cannot thus be completely filled; no, nor filled in any considerable degree. The art of landscape-painting will never become thoroughly interesting or sufficing to the minds of men engaged in active life, or concerned principally with practical subjects. The sentiment and imagination necessary to enter fully into the romantic forms of art are chiefly the characteristics of youth; so that nearly all men as they advance in years, and some even from their childhood upwards, must be appealed to, if at all, by the direct and substantial art, brought before their daily observation and connected with their daily interests. No form of art answers these conditions so well as architecture, which, as it can receive help from every character of mind in the workman, can address every character of mind in the spectator; forcing itself into notice even in his most languid moments, and possessing this chief and peculiar advantage, that it is the property of all men. [11.226]

If painting is less accessible than architecture to seeing and reading, then architecture, not painting, must be the model for a complete, ideal art. Architecture "can address every character of mind in the spectator." This duty of all art to demand full and active perception of every spectator is assumed in the third volume of Modern Painters when Ruskin discusses how great art must arouse and guide the imagination of the beholder. But there it is painting, not architecture, to which he refers.

The increased emphasis on the symbolic languages of art in the later volumes of Modern Painters is not simply to be explained by Ruskin's original plan (to treat the simpler ideas of truth and beauty before the more complex ideas of relation). His interest in reading visual art is a [208/209] corollary to his growing conviction that all aesthetic perception is active and, to some degree, interpretive. Ruskin's program for the spectator is at first more affected by this new notion of perception than is his own approach to paintings. His study of architecture between 1845 and 1853 helps to precipitate a shift from unanalyzed practice to conscious instruction in how to see and read art. That instruction is further elaborated and extended to the reading of paintings in Modern Painters III. There the Victorian tourist, both reader and subject of Stones is again invoked, but this time as the "eminently weariable" traveler through painted landscapes.

The imperative mood of Ruskin's "Read the sculpture" in Stones was not dictated solely by his discoveries about the nature of perception, however. His references to reading almost always suggest a real love, often felt with the force of a hunger, for multiple meaning in the visual aspects of things. The strong attraction to associative, nonlogical connections—extending from metaphor to puns—Ruskin shared with Turner (as Gage and Lindsay have emphasized),3 but what for Turner was a secular habit of mind for Ruskin also possessed a potential religious significance. The religious significance of figural reading is particularly evident in Stones. Reading iconography enters Ruskin's wi program for the ordinary spectator in part because Ruskin was defining his own vocation as an extension of a universal religious duty to read the created and written Word.

The special character of Ruskin's approach to figurative language, as we now realize, was greatly shaped by Evangelical exegesis of allegory and typology in the Bible, a kind of reading in which he was thoroughly trained by his mother and by nineteenth-century Evangelical ministers.4 Such reading presumed that the figurative language it interpreted was a "real" language, corresponding to a given external order. As Landow notes, Evangelicals maintained this assumption about the language of the Bible by virtue of a belief in literal inspiration (352-54). Ruskin inherited from his Evangelical teachers a schizophrenic approach to language. On the one hand, most language must be considered conventional, psychological, and historical; to figuralism viewed in this light, associative readings or historical analysis would be an appropriate response. On the other hand, biblical language, literally the words of God, must be questioned for another order of knowledge [209/210] Its figures could directly reveal the world from a divine perspective as opposed to a world refracted through the eyes and minds of particular cultures, periods, and individuals. The boundaries between these two kinds of language could not be neatly drawn. The Bible accustomed its believing readers to look at historical events both for their own instructive value and as types or antitypes of other events; by extension, natural objects were to be regarded for their own sakes and for their figurative significance. Reading for this kind of meaning was more than a habit; it had long been interpreted as a duty. Ruskin was quoting St. Paul, as many other Christian writers had done, when he wrote in Stones that "God would have us understand that this is true ... of all things amidst which we live; that there is a deeper meaning within them than eye hath seen, or ear hath heard; and that the whole visible creation is a mere perishable symbol of things eternal and true" (11.183 [i Corinthians 2.9]).

The status of language in art and literature for an early nineteenth-century Evangelical was unclear. As a record of the world, it might impose the same interpretive obligation as the events and objects it signified. As language particularly rich in figures, the obligation might be even stronger, especially if it could be shown that artist or author employed types or figures from the Bible, or had painted or written with a desire to portray the world as typically or allegorically significant. Such reading was applied by Evangelicals to texts such as Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress and Milton's Paradise Lost.6 Yet by the beginning of the Victorian period it was widely recognized that any language reflected the minds of the individuals and the cultures that used it. When and to what extent should the languages of literature and art be read as a third sacred book (after the Bible and nature), and when as an expressive and historical language of the human imagination? The peculiar intensity with which Ruskin approached the interpretation of symbolic languages in art seems to come partly from the sense of urgency attached to religious exegesis, and partly from the difficulties of reconciling conflicting conceptions of language to meet the demands of dual interpretation.

Ruskin does not really face the question of the status of language in art until Stones of Venice, but it is latent in Modern Painters I and II. Despite his emphasis on the expressive and associative character of great art in Modern Painters I, he praises it in terms of its relationship to [210/211] both the Bible and to nature considered as a divine book. Turner is a prophet of God and an angel of revelation (3.254,611, 630-31); artists are like preachers commenting on the nature-Scripture (3.45n). Similarly, Modern Painters II explores human imagination in thoroughly romantic terms but also treats at length typical ideas of beauty and insists that art is valuable as it enables men to fulfill what is their primary function from a religious point of view, "to be the witness of the glory of God" (4.28). The conception of art as human witness to or commentary on the divine Word was, then, already in Ruskin's mind when he made his delighted discovery, in 1845, of a medieval Italian art and architecture whose subjects and iconography were directly drawn from the Bible. His excited letters to his father reflect both purely visual pleasure and the pleasure of textual recognition. From Pisa he reported: "the Campo Santo is the thing. I never believed the patriarchal history before, but I do now, for I have seen it ... and the angels ... it is enough to convert one to look upon them—one comes away, like the women from the Sepulchre, 'having seen a vision of angels which said that he was Alive'" (Ruskin in Venice, pp. 67-68). He reveled in the churches "covered with holy frescoes—and gemmed gold pictures ... all the church fronts charged with heavenly sculpture and inlaid with whole histories in marble" (p. 51). The Italian art, even more clearly than Turner's, could be approached as a visual version of one of God's books.

As Ruskin begins to formulate his own identity as critic in the same year, he employs terms suggesting that he is flunking of the interpretation of art as a way of fulfilling the religious obligation to recognize deeper meaning in the created and written Word. He wonders, writing to his father, if his mission is really to study buildings and paintings (p. 157). A few years later he advises W. S. Stillman to pursue patient interpretation rather than prophecy or inspiration. His praise of religious reading suggests how much the distinction between religious exegesis and religious vision was on his mind in the period when he was making his own choice between artistic interpretation and artistic vision:

I can only imagine that by rightly understanding as much of the nature of everything as ordinary watchfulness will enable any man to perceive, we might, if we looked for it, find in everything some special moral lesson or type of particular truth, and that then one might find a language in the [211/212] whole world before unfelt like that which is forever given to the Ravens or to the lilies of the field by Christ's speaking of them . . . my advice to you would be on no account to agitate nor grieve yourself nor look for inspiration . . . but to go on doing what you are quite sure is right . . . accustoming yourself to look for the spiritual meaning of things just as easily to be seen as their natural meaning. [36.123-24]

The choice to read and interpret art is still more explicitly described as a discovery of religious vocation in retrospective accounts. In Praeterita Ruskin portrays 1845 as a year of discovering the power of art, beginning with the wall-scripture of Campo Santo and culminating, in Venice, with Tintoretto. His 1883 epilogue to Modern Painters II ties this series of revelations to a personal spiritual history. He set off for Italy, guiltily leaving his parents behind, "gloomy with penitence and ardent in purpose." In this temper of mind "the Campo Santo of Pisa was to me a veritable Palestine" (4.350). In both Praeterita and the 1883 epilogue, the vocabulary and structure of the accounts suggest that we are being told of a conversion experience. The final discovery of Tintoretto is its climax: Ruskin is called to criticism.

the Art of Man in its full majesty for the first time; and that there was also a strange and precious gift in myself enabling me to recognize it, and therein enobling, not crushing me. That sense of my own gift and function as interpreter strengthened as I grew older. [4.354]

The Stones of Venice is both Ruskin's first and his most sustained effort to combine religious and artistic reading in a single critical activity. The imperative Read embraces both religious and a more historical and psychological exegesis. Symbolic language in Seven Lamps and Stones is in fact a plural concept. Ruskin distinguishes at least four. The first is an invented symbolic language (the grotesques of sculptnral or pictorial iconography, 11.182-83, 205). There is also an "accidental" or "parasitical" language of the picturesque, where the marks of ag6 record the action of the elements on human artifacts, recalling the effects of time on the most massive and enduring natural objects (effects that would be sublime) and on men themselves (8.235-37). Finally, there are two natural symbolic languages that art and architecture may also employ: the historical language of stones (the marks ot [212/213] their development before they are used as human artifacts) and their theological language (11.38,41). The theological language of types is of course divine or "real"; what Ruskin calls the historical language of stones is also not a human one; it is the naturalistic basis for any real figurative language. The signs of the picturesque and the invented symbols of the grotesque are primarily human languages, however, though Ruskin has tried to bring them close to divine language. The marks of age in human artifacts resemble the historical language of stones—the signs of their natural history—but of course they depend upon the associating mind of the perceiver to function as language at all. They are conventional and associative signs, not real ones. The "symbolical grotesque" (11.178-84) is on the one hand a product of human imagination; on the other, of imagination in a state of inspiration. These symbols do not have the status of natural or biblical figures because in them meaning is refracted through the distorting glass of human perception, yet they do require religious exegesis because, though difficult and distorted, they may nonetheless be inspired vision.

When Ruskin reads Venetian Gothic in Stones he treats it as a thorough mixture of all these languages. Thus he points out that Venetian Gothic uses the natural grain of the marble in its designs—grain that could be read as natural history (11.38-39). It also exploits the varied colors of the stones, and color, according to Ruskin, has an allegorical meaning confirmed in the Bible (10.172-75; 7.417-19). Tourists to Italy will be especially responsive to the picturesque qualities of the buildings, the signs of age and decay, with their reminders of nobler mountain upheavals and of the endurance and suffering of the human builders—of fallen Venice.10 The stones also possess a typical meaning, as the famous first lines of Ruskin's history point out: the fall of Venice may be a type of the future fall of England. Finally, Ruskin treats the carved stones as expressive of the minds of the workmen and of their social and economic relations with their employers. He also explicates the symbolic meaning of the figures both by comparing them to other versions (Spenser, Dante, Giotto, a selection of French manuscripts) — a procedure that stresses their historical nature—and by glossing them directly from the Bible.11 Ruskin approaches the stones of Venice both as historical and artistic artifacts and as revelations of moral and religious truth. [213/214]

The half-sacred, half-secular interpretations of visual symbolism in Stones are, however, firmly linked to the Christian obligation to read for figural significance. In a passage with important implications for his own criticism, Ruskin pauses in "The Vestibule" to Gothic Venice—the last chapter of volume one—to justify the work of the artist.

Is there, then, nothing to be done by man's art? Have we only to copy, and again copy, for ever, the imagery of the universe? Not so. We have work to do upon it; there is not any one of us so simple, nor so feeble, but he has work to do upon it ... This infinite universe is unfathomable, inconceivable, in its whole; every human creature must slowly spell out, and long contemplate, such part of it as may be possible for him to reach . . . and in this he is only doing what every Christian has to do with the written, as well as the created word, "rightly dividing the word of truth." [9.409-10 (2 Timothy 2.15)]

But art, as Ruskin describes it, goes beyond the Christian obligation to analyze the written and created word. One must not only "spell out, and long contemplate" what one sees, but also

set forth what he has learned of it for those beneath him; extricating it from infinity, as one gathers a violet out of grass; one does not improve either violet or grass in gathering it, but one makes the flower visible; and then the human being has to make its power upon his own heart visible also, and to give it the honour of the good thoughts it has raised up in him, and to write upon it the history of his own soul. And sometimes he may be able to do more than this, and to set it in strange lights, and display it in a thousand ways before unknown: ways specially directed to necessary and noble purposes, for which he had to choose instruments out of the wide armoury of God. [9.409-10]

Ruskin's everyman moves imperceptibly from seeing, reading, and explicating the significant creation to inscribing (writing the history of his own soul) and to imaginative vision (setting the flower in strange lights). When he reaches inscription and vision, Ruskin's everyman has become an artist. The critical activities implied for the spectator of this art, like the creative activities of the artist described in Ruskin's paragraph, are all embraced by the paragraph's final clause: "and in this [214/215] he is only doing what every Christian has to do with the written, as well as the created word." In fact the criticism this art implies has been extended to include the interpretation not just of divine but of human written and created words. Both art and criticism are justified by their connection with Christian exegesis. But Ruskin seems to make room, in his description, for historical and psycho logical dimensions of visual language which, as we have seen, very much concerned him as well.

have suggested why, apart from his original plan to defer discussion of symbolism in art, reading is a more important part of seeing in Stones of Venice than it is in Modern Painters I or II. Urging every spectator to read architectural iconography was, by 1853, part of Ruskin's attempt to encourage more active, imaginative perception in the spectator-consumer as essential to cultural health. At the same time, such reading also fulfilled a religious obligation that Ruskin felt deeply, to read the divine languages of nature and the Bible, thus giving the sanction of a religious calling to his newly defined career as an art critic. In Stones the traditional, religious approach to symbolic meaning seems to be just what is needed to complete the reform of the modern tourist into a sensitive, historically self-conscious patron of the arts. After they have learned to look at Gothic architecture, travelers must learn to read the lessons of both carved stones and contemporary histories. In this first attempt to interpret the symbolic languages of visual art, Ruskin uses Christian exegesis as a model for all aspects of the tourist's encounter with symbolism in art.

Ruskin, however, continues to emphasize reading when he returns from his detour into architecture and history to what he later saw as his proper territory (35.372), modern painting. And in that territory the kind of reading he advocated in Stones seems—to twentieth-century formalists no less than it would have seemed to Hazlitt — decidedly out of place. One may read the mosaics of St. Mark's or even a Hogarth; one does not read a Turner. Imaginative modern art does not employ explicit symbolism, to be glossed by literary texts and translated into verbal interpretation, as a major part of its appeal to the spectator. "Literary" art is not good art. The judgment is very much a romantic one. Ruskin may seem at odds both with his subject, the great romantic painter, and with his own romantic criticism in Modern Painters I [215/216] when he insists, in Modern Painters V, that we read Turner's paintings. But Ruskin's method of reading modern paintings can be traced to acceptable romantic responses as well as to traditional exegesis. He seems to have consciously tried, in the last two volumes of Modern Painters, to reconcile the two kinds of response to art on new grounds—this time thinking not just of the workman and the tourist in Gothic Venice, but of the romantic painter and his Victorian audience as well.

One can argue, though with some caution, that Ruskin's approach to Turner's painting in Modern Painters V has much in common with his more visual approach in Modern Painters I. His readings rely on the same habits of mind as his excursive and associative seeing. For example, both approaches are piecemeal methods. That is, they piece together a notion of a whole through attention to significant details. Starting from a belief in the necessary incompleteness of perception, both stress the need for constant reinterpretation from different points of view as the only way of approximating grasp of a total design. Again, neither is reductive, emphasizing instead the surplus of information in any sign. Words or images may always mean more than the sum of their figurative meanings. They have literal importance and multiple figurative significance; the two kinds of significance are overlapping but not exactly coincident. I have argued in earlier chapters that the piecemeal or excursive approach and the high valuation of unreduced visual detail in Ruskin's criticism of the visual arts owe much to a mode of seeing associated with gardens, travel, and associationist poetics. But one might also argue that these same traits, when they appear in Ruskin's readings of visual or verbal symbolism, are derived from the exegetical tradition with which he was so familiar.

The practical similarities between exegetical reading and excursive seeing may begin to suggest why and how Ruskin read Turner's paintings. Ruskin's argument for reading Turner's art as symbolic language is still more revealing. Ruskin evidently planned to conclude Modern Painters by showing that both Turnerian and biblical symbolism, though one was a human language and the other divine, required the same sort of reading. Modern Painters IV and V explore the physical effects of clouds on light as the natural phenomena in biblical metaphors of clouds as the veils, temples, robes, and dwelling places of God. This discussion prepares us for the final examination of Turner's [216/217] cloudy art. The term "cloudy" as applied to romantic art—by Ruskin in Modern Painters III and by other critics before him—describes both a major subject of that art and a technique—in painting, the use of light and color to fill space and suggest, without fully realizing, complex form. By extension, suggestive technique may also mean allusion or metaphoric suggestion to the associative imagination; hence the frequent use of mist or cloud as a figure for the imagination in the poetry of Wordsworth. When Ruskin dealt, in Modern Painters V, with what he rightly saw as Turner's highly metaphoric art, he used Turner's treatment of cloud, light, and color to discuss the special nature of imaginative symbolism in romantic art. But he also related that use of symbolic language, exploiting physical facts of light and color, to symbolic language in the Bible. In these last two volumes of his defense of Turner he set out, I believe, to use what he read as the biblical (and natural) metaphor for symbolic language, the clouded heavens, as his vehicle for bringing together allegorical and romantic symbolism.

Ruskin's second attempt to reconcile two approaches to symbolic language is thus an argument both from and through metaphor or, more precisely, two metaphors superimposed: the veil of allegory and the transforming mist or clouds of romantic imagination. Reading romantic art is justified not only as religious obligation but also as an appropriate imaginative response. But Ruskin's argument only makes sense if we look closely at the texts and paintings from which he takes his metaphors. For the biblical sense of the cloud-veil, Ruskin uses passages from Genesis and Psalm 19; for its modern meaning as a figure for imagination, he takes modern landscape painting and its poetic counterpart, typified by Scott.

In the middle of Modern Painters IV Ruskin starts his defense of Turner afresh, going back "to trace, with more observant patience, the ground which was marked out in the first volume" (6.104). The new treatment of the truths of nature (chapters on mountains, vegetation, and clouds) is specifically concerned with these truths as constituting a symbolic language that needs reading. These chapters explain visible aspect by detailed descriptions of physical composition and natural history, leading in each case to conclusions about the "typical significance" (6.153), "ministry to ... man" (6.160) or "appointed" meaning (6.172) to be interpreted from natural phenomena. The section begins [217/218] and ends in the clouds—not Turnerian skies but the biblical firmament, which Ruskin interprets as a figure for the kind of symbolic language he is reading in the visible aspects of things. The section as a whole comes just before the closing section on invention in art, most of which is devoted to the discussion of painting as a "vehicle of thought" promised in the first volume. That section too begins in the clouds, the cloudy mirror of the human imagination. It comes to a climax with Ruskin's readings of two examples of Turner's cloudy symbolism. The notion or two kinds of symbolic language seems, then, to have determined the structure of these sections: one on the sacred languages of landscape, both historical and theological; followed by a second on the invented symbolism of imaginative painting. As in The Stones of Venice, where the two kinds of symbolic language are first recognized and distinguished, Ruskin wants not to separate them but to discover ways in which the second overlaps or coincides with the first

by examining what the real effect of the things painted—clouds, or mountains, or whatever else they may be—is, or ought to be, in general, on men's mind, showing the grounds of their beauty or impressiveness as best I can; and then examining how far Turner seems to have understood these reasons of beauty, and how far his work interprets, or can take the place of nature. [6.104]

This way of presenting his plan for ending Modern Painters still suggests the controlling analogy between the painter and the interpreter of nature's sacred text. The promised discussion of invented symbolism is subordinated to the duty—for both painter and critic—to interpret typical or intended natural meaning. By the time Ruskin actually writes the closing section on imaginative symbolism, that analogy has broken down. Nonetheless, Ruskin is faithful to what seems to have been his original intent: to find some means, metaphorical if necessary, for treating two kinds of symbolic language from a single critical perspective.

Ruskin's opening chapter on biblical clouds, "The Firmament," sets forth the exegetical techniques of the Evangelical sermon as the proper method for a renewed study of nature. This introductory chapter uses a reading of the opening verses of Genesis to reflect on the verbal and visual languages of God, much as Augustine, a central figure in the [218/219] earlier exegetical tradition, had used the same verses in the last three books of his Confessions. Ruskin is primarily interested in the created or visible Word, the divine language of Nature; Augustine, in the written Word, the divine language of the Bible. But both use the Genesis account of creation to draw an analogy between the written and the created word, and both turn their own interpretations of one or two verses into an examination of principles of reading and the nature of language applicable to created and written word alike. The comparison between the explications illuminates both what Ruskin shared with traditional patristic exegesis and where he departed from it.12

Both Augustine and Ruskin use the creation story not only to affirm parallels between the created and the written word, but also to elucidate a parallel structure of two different levels of truth within each divine language. Augustine distinguishes between the intellectual heaven of Genesis 1:1 and the created or visible heaven of Genesis 1:6-8, comparing the distinction to that between divine truth as it appears to the mind of God and as it is expressed in the language of the Bible.13 The relation between the two orders of truth is that of division from the single truth to multiple, fragmented, and less perfect forms of it. This fragmented visible heaven, or readable language, imposes upon the Christian the duty of collecting and interpreting. If it is the nature of truth, in the world in which men must live and the Bible was written, to be multiple and divided, then perception and understanding are never single or complete. The only way to approach unity of comprehension is through analyzing, comparing, and gathering together many different perceptions of the "beautiful variations" of the universe or of figurative language.14 Criticism, then, must expand and multiply meaning through "longer and more involved discussions" before it can contract it into a single whole (328, Book 12, chap. 27). This continual seeking and gathering together of bits and pieces of the truth—felt by Augustine as his most impelling desire and echoed much later in Milton's famous phrase16—could very well describe Ruskin's conception of the proper way to perceive a building or a landscape or a painting, or the right way to read a biblical text. We might also note that Augustine's attiude toward the visible creation, despite his desire to recover the undivided truth, is not reductive; the beautiful variations or many breams flowing from a single fountain17 are a source of positive pleasure. [219/220] Abundance and variety are highly valued in both verbal and sensible worlds. Here, too, an exegetical approach to visible things as divine language produces an attitude very similar to what we have identified as Ruskin's and traced through a secular tradition of landscape experience.

In his introductory chapter, Ruskin similarly contrasts a remote heaven, "the infinity of space inhabited by countless worlds" (6.in) or the "blackness of vacuity" in which the "intolerable and scorching circle" of the sun is set (6.113), with the nearer, finite, variable, and more easily visible aspect of the heavens described in Genesis 1:6-8, the "ordinance of clouds" (6.112). This relationship in the created world between infinite and finite, eternal and temporal, invisible or inconceivable and visible and comprehensible parallels the relationship between the whole truth of God and the divided or obscured truth of figurative language in the Bible. Ruskin's further and nearer heavens, however, realize Augustine's metaphors for their relationship as natural fact. Augustine's major metaphor, that the intellectual heaven or truth is divided into the created heaven or figurative language, becomes, in Ruskin's version, "by the mists of the firmament his implacable light [the sun] is divided, and its separated fierceness appeased into the soft blue that fills the depth of distance with its bloom, and the flush with which the mountains burn" (6.113).

A second common metaphor, in Augustine and allegorical tradition in general, speaks of figurative language as the veil of divine truth. In Ruskin's naturalistic interpretation of the metaphor this becomes

"In them [the clouds] hath He set a tabernacle for the sun" [Psalm l9:4] whose burning ball, which without the firmament would be seen but as an intolerable and scorching circle in the blackness of vacuity, is by that firmament surrounded with gorgeous service, and tempered by mediatorial ministries ... by the firmament of clouds the purple veil is closed at evening round the sanctuary of his rest. [6.113]

To the metaphors of dividing and tempering or veiling the truth Ruskin has added, on the authority of other scriptural passages, a third:

that of housing or robing it in a gorgeous splendor of varied color, in the light-filled, colored clouds the Bible calls God's tent, temple, or tabernacle. Ruskin's cloudy heaven is both itself one of the veiled, divided, or apparelled manifestations of divine presence and a figure for divine symbolic language in general. [220/221]

This figurative reference is brought out more clearly in a passage from Modern Painters V, the introduction to chapters on the physical nature of clouds, in which the creation is again recounted:

the heavens, also, had to be prepared for his [man's] habitation.

Between their burning light,—their deep vacuity, and man, as between the earth's gloom of iron substance, and man, a veil had to be spread of intermediate being; — which should appease the unendurable glory to the level of human feebleness, and sign the changeless motion of the heavens with a semblance of human vicissitude.

Between the earth and man arose the leaf. Between the heaven and man came the cloud. [7.133]

Here the function of the cloudy firmament is not only to veil but also specifically to "sign"—to be a language for human readers. Ruskin finds his authority for taking clouds as natural signs of divine manifestation from the Bible, citing some twenty-four passages in the course of his chapter on the cloudy heavens of Genesis 1:6-8. The effect of Ruskin's chapter, then, is to confirm, in the physical facts of nature, the literal truth of biblical figures and traditional exegetical metaphors for the relation of figurative language to divine truth. Or one might put it the other way around: he uses scripture as a guide to what aspects of the visible creation are intended to be significant. The Bible is source and authority for an explication of natural symbolism. In any case, we might note that Ruskin's chapter on the creation of the heav- ens diverges from Augustine's in two ways. Ruskin ties the biblical language much more closely to observed natural fact, and he also puts special emphasis on one aspect of clouds that neither Augustine nor the Bible especially brings out: their gorgeous color. The firmament as a veiled manifestation or divinity is specifically cloud through which light has been divided, appeased, and softened into color.

Like Augustine, Ruskin goes on to use his gloss on the creation story to offer rules for the right reading of biblical and of visible language. His precepts conform closely to contemporary Evangelical practice. The readings of stones or clouds or trees in the succeeding chapters follow and illustrate these precepts. Ruskin pays careful attention to discriminating signs by context, distinguishing stones of foothills from stones of high mountain peaks. He insists that we look first for details accessible to the ordinary eye. The literal—in the case [221-222] of stones, geological and physical—significance of these details is his first concern; other meanings must be consistent with physical or geological fact. Ruskin then compares the varying effects of these stone signs on human perceivers, drawing on literature and art as well as common experience for testimony. He collects multiple possibilities for symbolical meaning in stones or clouds—meanings for which the Bible, however, is the ultimate guiding text.18 Here, as in Stones, Ruskin's exegetical practice is consistent with Ins excursive and associative habits and with his concern for detail.

Ruskin's stress on a naturalistic basis for biblical metaphors constitutes an argument for a coincidence of biblical and natural symbolism. As such it is a departure from the usual argument for God's two parallel, but separate, books, as made either in traditional patristic exegesis or by nineteenth-century Evangelicals. The departure is most evident in Ruskin's explication of Psalm 19, with which he concludes his section on natural symbolism (7.193-99). That psalm, as has long been recognized, breaks into two equal parts, the first in praise of the creation, the second in praise of God's law. It was often read as moving from a lesser to a greater revelation, but among Puritans or Evangelicals from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, it was quite commonly interpreted as praise for the two equal books of God (69). For example, C. H. Spurgeon, whose sermons Ruskin frequently attended in the late fifties and early sixties, begins his commentary by reaffirming the parallel revelations of the two books:

In his earliest days the psalmist, while keeping his father's flock, had devoted . himself to the study of God's two great books—nature and Scripture; and he had so thoroughly entered into the spirit of these two only volumes in his library that he was able with a devout criticism to compare and contrast them, magnifying the excellency of the Author as seen in both. How foolish and wicked are those who instead of accepting the two sacred tomes, and delighting to behold the same divine hand in each, spend all their wits in endeavouring to find discrepancies and contradictions. We may rest assured that the true "Vestiges of Creation" will never contradict Genesis, nor will a correct "Cosmos" be found at variance with the narrative of Moses. He is wisest who reads both the world-book and the Word-hook as two volumes of the same work, and feels concerning them, "My Father wrote them both." [p. 304] [222/223]

Spurgeon's pointed warning against the dangers of using science to disprove the literal truth of the Bible should remind us that Ruskin's reading is similarly defensive. He had himself, at least as early as 1851, felt "those dreadful Hammers" of the geologists as a threat to Evangelical belief in the literal truth of the Bible (36.115). His reading of Genesis and of Psalm 19 is likewise addressed to this threat.

But Ruskin's explication of Psalm 19 goes beyond Spurgeon's concerns to show that nature and revelation, of equal value, do not contradict each other. His reading seems intended to justify the figurative language of the Bible, not by showing that scientific natural history and the divine history of the Bible are compatible, but by showing how the biblical figures make precise and detailed reference to the physical facts of the natural world.21 Ruskin seems to be arguing, in other words, not that the content of the two books is compatible or identical, but that they use the same language or symbolism, translated into different media. According to this view, nature and the Bible would be a closely related text and picture, to be considered or interpreted side by side—works in two media by the same author sharing a common symbolism and intended to be looked at together.

Ruskin reads Psalm 19 with a peculiar intensity and ingenuity not found in other commentaries. The psalm begins "The heavens declare the glory of God. And the firmament sheweth His handiwork" and moves to a description of the sun running through the course of the heavens, tabernacled in the cloud. Verses 7-14 praise the law in six terms: as law, commandment, testimony, fear, statute, and judgment. Neither Augustine nor anyone else that I have found attempts to distinguish between heavens and firmament in Psalm 19, much less to carry that distinction, as Ruskin does, into a reading of two kinds of verbal revelation in the second half of the psalm. Ruskin sees in the first part of the psalm a distinction between two manners in which the heavens or created things speak to men: as "the great vault or void, with all its planets, and stars, and ceaseless march of orbs innumerable," especially the sun; and as the firmament or "ordinance of clouds" (7.196). The former declare; the latter show, instruct, teach, or guide. The former are eternal, the latter variable, changing according to present circumstance in the world of the perceiver. Ruskin then goes on to find the same distinction running through the second [223/224] part of the psalm, between an eternal, fixed law (testimony, statute) that is simply declared and the word of God as it is modified to instruct men of varying capacities for understanding in a changing present. Commandment, fear, and judgment describe the law in its temporal or mediated form: addressed to the specific needs and acts of men of limited perception. Visible properties of sun and cloud are invoked to gloss this double-natured word. The gloss strongly implies that the second form of that word is figurative, or at least that it requires interpretation on the part of the reader. The law is fixed and clear; commandment is "often mysterious enough, and through the cloud" (7.198). Whereas the traditional reading of the psalm simply states that both the created world and the written word are the books of God, Ruskin's reading makes the psalm speak of the nature of divine language or, rather, its double nature, for which there are exact equivalents in the visible world and the verbal law. Furthermore, his reading points to one of the major conclusions he would draw from this fact: that the visual text and the verbal one have to be read together, the relation of firmament to heavens elaborating the relation of figurative language to direct revelation.

We can see also that the distinction Ruskin finds in Psalm 19 is a version of what runs through his writing on the perception of landscape and visual art, a distinction between two modes of seeing or comprehending. Only one of these modes is really possible for the ordinary man: the excursive exploration of particular aspects of a larger whole, or the interpretive reading of truth veiled in figurative language. The man of inspired vision may grasp the terrible sublimity of the law or look in the face of the sun, as Turner sometimes does, but even he will be unable to convey what he has seen except through an invented symbolic language. The man of ordinary perception will have to follow the commandments in order to know God. Seeing and reading, like moral action, are ways of approaching a desired state of knowledge. Moral, perceptual, and imaginative activity must be both continual and continually guided. Viewed in this light, seeing and reading arc forms of moral action; they are the duty of every man, distinct from the privileged vision of the artist, poet, or prophet.

Just as Ruskin's exegetical background provided religious motivation for interpretive or critical activity, so it also provided a religious explanation of imaginative perception as distinguished from imaginative [224/225] vision—or the beholder's and reader's as distinguished from the artist's and poet's approach to visual and verbal language. In Modern Painters IV and V Ruskin begins from but alters traditional readings of biblical texts so that they describe two modes of revelation—direct and figurative—both of which may be found in nature or the Bible, but best understood when verbal and visual versions are considered together. His readings also imply two corresponding responses, but strongly suggest that cloudy revelation or figurative language will necessarily be the central concern of every reader and perceiver. His scriptural readings seem quite deliberately to lay the groundwork for a final discussion of Turner's cloudy art.

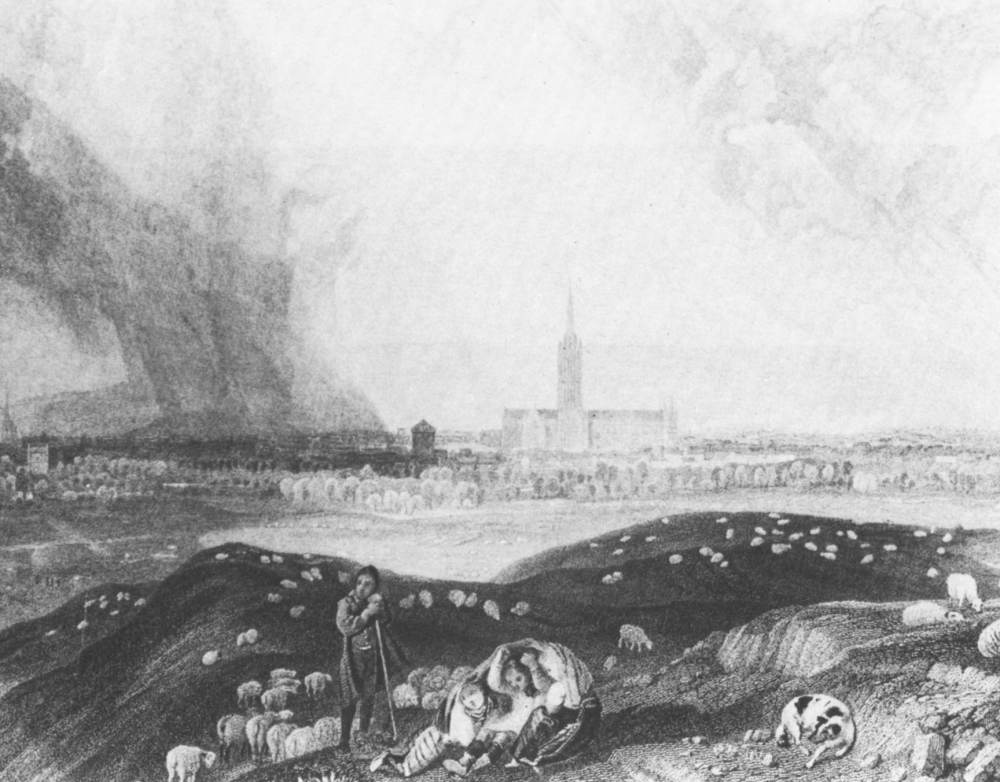

We can now see, I think, how Ruskin might have concluded Modern Painters by arguing that Turner's art was a faithful use of divine figurative language drawn from nature and the Bible. Turner's love of complex allusion (including the use of texts to accompany his pictures), his use of a naturalistic mythological symbolism, and the importance of colored clouds and a cloudy technique to his symbolic visual statements might all indicate that he was using the figurative language described—by Ruskin's reading—in Genesis and Psalm 19. Indeed, just before he explicates the psalm Ruskin points to Turner's paired engravings Salisbury and Stonehenge as examples, respectively, of the beneficent and fearful aspects of the divine language of clouds.

Salisbury from Old Sarum Intrenchment. Stonehenge by Turner. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

Before we look further at Ruskin's readings of Turner in Modern Painters V, however, I want to go back to some of Ruskin's earlier comments on color and clouds in romantic painting and poetry. Ruskin had already in Modern Painters I extended to painting the romantic preference for an incompleteness or deliberate lack of finish which would demand imaginative participation from an audience. This suggestive incompleteness, taken as both sign of and stimulus to imagination, had been associated with mist and cloud in a long line of criticism and poetry, from Burke through Wordsworth and Shelley. Ruskin's characterization of modem art and literature as cloudy in Modern Painters III exploits this usual association with imagination and points out, in addition, that this art is both literally full of clouds and excessively gloomy (5.317-19, 320-22). Modern Painters III considers romantic cloudiness in its most negative aspect. The defense of Turner that Ruskin begins here seems to be designed to demonstrate that romantic [225/226] cloudiness has been modified so as to avoid some of the negative aspects of modern landscape feeling and aesthetic technique.

That defense is made first with respect to Scott. As noted earlier, Ruskin calls Scott the representative romantic writer but dwells on a crucial distinction between Scott's landscape descriptions and those of other romantic poets. Like Turner, Scott does not employ pathetic fallacy. Scott is also important to Ruskin because his descriptions, again like Turner's paintings, are typically full of clouds and a slight melancholy feeling, without falling into what Ruskin views as two major weaknesses of romantic cloudiness, especially in painting: the absence of detail and the absence of color. In Scott's poetry "the love of natural history, excited by the continual attention now given to all wild landscape, heightens reciprocally the interest of that landscape, and becomes an important element in Scott's description, leading him to finish, down to the minutest speckling of breast, and slightest shade of attributed emotion, the portraiture of birds and animals" (5.350). The quotations from Scott that Ruskin chooses to illustrate his argument also demonstrate some very Turnerian effects of cloud and color, as in Scott's description of Edinburgh:

The wandering eye could o'er it go,

And mark the distant city glow

With gloomy splendour red;

For on the smoke-wreaths, huge and slow,

That round her sable turrets flow,

The morning beams were shed,

And tinged them with a lustre proud,

Like that which streaks a thunder-cloud.

Such dusky grandeur clothed the height,

Where the huge castle holds its state,

And all the steep slope down,

Whose ridgy back heaves to the sky,

Piled deep and massy, close and high,

Mine own romantic town!

But northward far, with purer blaze,

On Ochil mountains fell the rays,

And as each heathy top they kissed,

It gleamed a purple amethyst.

Yonder the shores of Fife you saw,

Here Preston Bay and Berwick Law; [226/227]

And, broad between them rolled,

The gallant Firth the eye might note,

Whose islands on its bosom float,

Like emeralds chased in gold.22

Ruskin says nothing about the verbal skill of these lines; what he notes are the painterly habits of eye: "there is hardly any form, only smoke and colour . . . observe, the only hints at form, given throughout, are in the somewhat vague words, 'ridgy,' 'massy,' 'close,' and 'high'; the whole being still more obscured by modern mystery, in its most tangible form of smoke. But the colours are all definite; note the rainbow band of them—gloomy or dusky red, sable (pure black), amethyst (pure purple), green, and gold—a noble chord" (3.347-48). Such passages lead to Ruskin's praise for Scott's "colour instincts" (3.348); despite his modern cloudiness, "the love of colour is a leading element, his healthy mind being incapable of losing, under any modern false teaching, its joy in brilliancy of hue" (3.346).

These two differences between Scott's colorful, detailed descriptions and much romantic cloudiness are those Ruskin stresses in his discussions of Turner. Turner's lack of finish is never emptiness or absence of detail; his paintings are characterized by their abundance of visual material, presented in an incomplete and suggestive form. Ultimately his gloomy clouds become gloriously colorful. The first of these arguments for Turner's distinctive greatness we followed in some detail in Modern Painters I', it is also the burden of the chapters on "Finish" and "The Use of Pictures" in Modern Painters III and of those on "Mystery—Essential" and "Mystery—Wilful" in Modern Painters IV. The implications for the spectator of Turner's suggestive detail are particularly important to Ruskin. Turner's work is indeed designed to awaken imagination, but the spectator's imagination is never left free to follow its own train of visual and mental association wherever it pleases. Turner's paintings require continuous close visual attention, a prolonged and detailed exploration: like the language of scripture, the commandments of God, they are designed to guide and they must be followed, letter by letter or image by image. In his stress on the demands placed upon the spectator Ruskin is trying to correct what he considers a fault in romantic poetics. In "The Use of Pictures" he distinguishes between painting that will most please the romantic poet (Wordsworth is his example) and painting that is a significant imaginative [227/228] achievement. The poet will prefer the splash of ink on the wall because he can use his own rich imagination to create whatever he likes out of it, but a great imaginative picture will be necessarily far more structured and detailed. It will also require the imaginative participation of the spectator—its technique will be suggestive—but the spectator's imagination will be guided, both visually and associatively. A great painting will deliver an impression of visual and imaginative unity only if the spectator follows its suggestions quite carefully, on the level of the smallest details of color, line, and composition.

The difficulty that Ruskin finds in romantic poetics—as I suggested in Chapter 2— is that there is no clear distinction between imagination in the poet or artist and imagination in the reader or spectator. The consequence is likely to be drastically lowered standards for poetry or art: the criterion of suggestive art can produce art that is, instead, simply vague. Ruskin saw the threat to literature as well as art—in Wordsworth's undervaluing of visual detail and separation of sight from thought, for example—but he was particularly concerned with the many inferior artists influenced by Turner and, more important, with the inability of the public to distinguish between Turner's cloudy pictures and the random splash of paint (soapsuds, Hour, and spinach—as critics described Turner's late paintings).23 It is important to realize that Ruskin is not rejecting incompleteness or suggestiveness of technique; on the contrary, his original defense of Turner in Modern Painters I singles out Turner's associative rendering of space and form as the major difference between his and earlier landscape art. It is also important, however, to see that Ruskin was suggesting ii modification of the romantic aesthetic of incompleteness as it affected the experience of readers and spectators. His response to suggestive detail was, I think, much closer to an alert and sensitive experience of nonsublime scenery encountered in the course of travel; it was also, though, very much a characteristic of exegetical reading.

The second difference between Turnerian and romantic cloudiness is that cloudiness is associated with literal gloom or darkness in modern painting, whereas Turner, in the second half of his career, is preeminently the painter of clouds as brilliant light and color. Ruskin's objection to the gloom of modern cloud painting in Modern Painters III is both aesthetic and emotional or moral. He clearly values color on purely visual grounds, but he also connects attention to brilliant color [228/229] with cheerful or optimistic states of mind, and optimism and pessimism he links in turn with periods of faith and doubt. As early as Stones he calls color sacred and singles out the vibrant color of Venetian Gothic as a sign of religious temperament (10.172-175). With few exceptions, he finds no great colorists among modern painters. Like a small but growing number of English artists and collectors in the first half of the nineteenth century, Ruskin discovered color not only in the late Venetians—Titian had always been acknowledged as a great colorist—but also in the early Italian painters and—for Ruskin—in Venetian Gothic and illuminated manuscripts. All three kinds of highly colored art, of course, were products of an age of Christian faith. Use of color combined with religious subjects was evidently a major reason why Ruskin was drawn to the English Pre-Raphaelites. In their love of color the Pre-Ralphaelites had something in common with Turner as well as with the early Italians, but the Pre-Raphaelites and the medieval painters, as Ruskin takes care to point out, do not use the cloudy technique of Turner where color suggests space and form.

In 1851, when he compared Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites at length, he distinguished two ways of using color: in a technique of clear definition of detail, without modeling or depth of space; or in a technique of suggested detail with great attention to depth and fullness of space (12.359-60).25 Ruskin leaves no doubt, in 1851, that he considers the second or cloudy technique superior because more imaginative. With their slow, painstaking method of covering a canvas detail by detail, rather than rapidly sketching in the whole design from the start, the Pre-Raphaelites would illustrate the process of attentive sight in the ordinary spectator rather than the marvelous grasp of the imaginative artist. Ruskin's attitude toward them is one of expectation and encouragement rather than of praise for achievement; he hopes that their attentiveness will be the basis of a future imaginative art. For the moment, one suspects, the Pre-Raphaelites were useful to him in Ins attempts to modify romantic approaches to imaginative art and literature. At least they might be useful, if he could convince his readers that Turner's cloudy paintings were based on a similar care for observed detail and for color—and demanded the same informed attention, as say, the botanical marvels in the foreground of Millais' Ophelia.25

Ophelia by Sir John Everett Millais and a detail of the vegetation. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

But Ruskin saw a further link between Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites [229/230] They were not only colorists but interested in explicit symbolism as well. Hunt and Rossetti employed types and allegories taken directly from or modeled on the figures of scripture, as understood in exegetical tradition. Ruskin stressed in his reviews that these pictures needed to be read.26 Use of typology made yet another link with the early Italian painters: medieval and nineteenth-century Pre-Raphaelites combined deliberate use of "that great symbolic language" of scripture and nature with great sensitivity to "the sacred element of color." Ruskin's discussions of medieval art and Pre-Raphaelitism might be read, then, as efforts to create the appropriate context for understanding how Turner's symbolic art modifies the gloom and the vagueness mistakenly assumed by critics, careless spectators, and inferior painters to be a sign of imagination in romantic art.27 Within this context we might conclude that Turner's brilliant color and explicit symbolism indicate a kindred religious temperament, but one consciously working not in the manner of direct revelation, but rather in that figurative language "often mysterious enough, and through the cloud." The active, imaginative perception required of the romantic spectator of Turner's paintings could then be understood as a modern analogue for the moral activity of interpretation required of the reader of God's word in Psalm 19. Ruskin has considerably refined the meaning for a spectator of his first hyperbolic praise of Turner as "a prophet of God . . . standing, like the great angel of the Apocalypse, clothed with a cloud, and with a rainbow upon his head."

Ruskin's argument for reading the romantic symbolic art of Turner as one would read divine figurative language—if an argument by association and metaphor can be called an argument—depends finally on demonstration. That is, as with Ruskin's ideas about the proper visual response to paintings and landscape, metaphoric descriptions of that activity as traveling or perceiving light transmitted through cloud or as following scriptural commandment may prepare us for what Ruskin wants us to do by suggesting that certain attitudes or modes of perception will be appropriate. But the clinching argument, or the most important persuasive activity, is the experience he gives us of reading a Turner painting in his manner. Modern Painters begins with the stunning descriptions in which Ruskin takes his readers through

Turnerian landscapes, delighting and sometimes overwhelming them [230/231] with what it means to see as Ruskin does. The fifth volume ends with examples of what it means to read romantic painting. These examples should, we expect, give experiential meaning to the cloud gazing developed so carefully in Modern Painters III, IV, and the first part of V. So they do—but the experience turns out to be an ironic version of the one we were led to expect. Before he finished his interpretations of Turner's symbolic art, Ruskin had changed his mind about both Turner's cloudy language and God's. His readings of Turner's The Goddess of Discord in the Garden of the Hesperides and Apollo and Python must be considered separately as a third attempt at a consistent approach to symbolic language. [231/232]

Last modified 7 April 2024