This review first appeared in the Times Literary Supplement of 15 October 2021, under the title of "Get over it: The impact of the uncertain, meandering course of convalescence on literature." The author has extended, reformatted and illustrated it for the Victorian Web, adding links, illustrations and captions. All images except the first and last are taken from our own website. [Click on them to enlarge them, and for more information about them where available.]

An age of frequent epidemics, the nineteenth century also brought advances in medical treatment. Good aftercare for the partially recovered, whether at home or in an institution, became a priority — witness the numerous convalescent homes set up from the early 1840s onwards to cater for a wide range of patients, from debilitated working-class children to newly discharged asylum inmates. In this study, Hosanna Krienke focuses on the literary uses of convalescence in its Victorian heyday. Long periods of recuperation feature in novels as diverse as Dickens's Bleak House, Elizabeth Gaskell's Ruth, Samuel Butler's Erewhon, Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone and Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Secret Garden. These are the subjects of Krienke's five main chapters, but, in each case, there are extra dimensions to her discussion. Among the topics she explores are differences in the treatment of classes, gender and age; the provision of spiritual support; care for the mentally afflicted; and the deleterious effects on health of the colonial experience, especially warfare in the service of empire. Her book has a roughly chronological trajectory, but, since she posits that "convalescent ideology permeated Victorian culture as a whole" (11), the boundaries are porous — and that brings new insights. She finds, for example, that the idea of rehabilitation grew out of the experience of helping soldiers recuperate in Indian hill stations like Darjeeling, rather than out of dealing with veterans of the First World War.

The Metropolitan Convalescent Hospital, Walton-on-Thames, thought to have been the first purpose-built convalescent home in the country. It opened in 1854.

Esher Summerson in nursing mode in Nurse and Patient, by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), showing her nursing her child-maid, Charley.

Krienke's main purpose, however, is to illuminate the text, and, more specifically, to show the impact of the uncertain, meandering course of convalescence on every aspect of it. In Bleak House, for example, she focuses on "Miss Flite’s circumscribed health outcomes, Esther’s equivocal improvements, and Caddy’s partial rehabilitation," and finds that "the laborious rehabilitations ... serve not to establish closure but to emphasize the ponderous social difficulties that thwart simplistic ideals of recovery and resolution" — yet also to show a way forward through "pragmatic portrayals of ameliorative action." This in turn provides "a narrative paradigm through which to track modest, or perhaps, merely middling change" (42). The effect on the sheer pacing of the narrative is even more noticeable in Ruth, where, as Krienke points out, there is an accumulation of "convalescent plots" (49). Convalescence and its outcome have previously been seen to contribute to the ending of a novel, but, typically, Krienke turns here to the (so far) less theorised middle chapters, where a period of refreshment and renewal of strength can play an essential part, especially within the "eschatological framework of divine punishment or redemption" (51). Once again, the progress of those characters who need such a period of recuperation is by no means straightforward, especially in view of their spiritual lives:

Throughout the plot, characters’ rehabilitations present seemingly legible spiritual meanings that, on closer inspection, do not quite fit the evidence: Bellingham’s prolonged recovery from brain fever could perhaps illustrate his irritable character; Benson’s physical disability possibly causes his ethical quandaries; Richard’s survival of an accident appears to prompt his repentance. Repeatedly, the narrative form undercuts these interpretations even as it presents such readings as plausible. [51]

As part of her own "years-long process of spiritual maturation" (51), Ruth herself has a difficult period of recovery after childbirth, which Krienke links successfully with the large number of convalescent devotionals being written by the adherents of the different denominations. Even though Ruth dies at the end of the novel, Krienke argues, this long period at least serves to complicate the kind of facile connection made between her early fall from grace and her eventual fate. Her death need not, in fact, be taken as a punitive final judgement on her, but as part of an ongoing debate: in Krienke's opinion, "Gaskell simultaneously acknowledges the easy legibility of this connection and positions such an interpretation as ethically suspect" (72). As elsewhere, Krienke's critical stance is subtly but clearly argued and has the welcome effect of opening the novel to a wider range of possible readings.

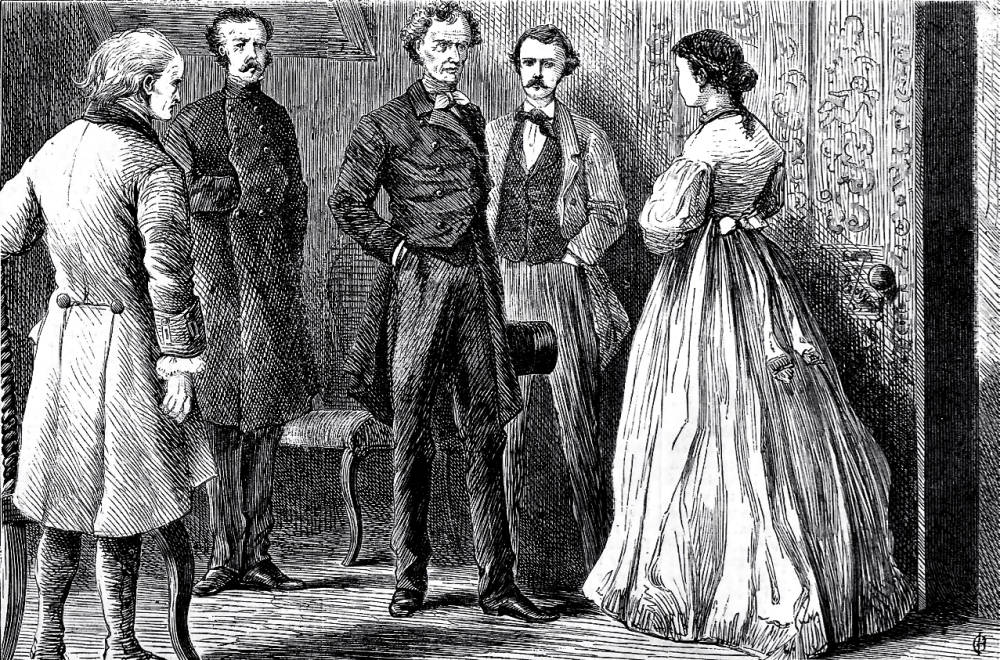

Sergeant Cuff's immovable eyes never stirred from off her face — an illustration for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly. Three of the narrators are shown here as Rachel Verinder tries to stand up to questioning: Gabriel Betteredge (left); Sergeant Cuff (centre); and Franklin Blake (right).

This kind of "opening up" is one of Krienke's aims, and it is a laudable one. Thinking more specifically of the reader in her next chapter, she suggests that the very experience of temporary withdrawal into the fictional world can be restorative, offering a healthy broadening of sympathies. This is hardly a function particular to any one work. Nevertheless, she makes a good case for seeing Collins's complex narrative in The Moonstone as an unusually rich example of the process. There are, after all, nearly a dozen different narrators, who between them address readers of different classes, ages and genders, and sometimes expect the reader to keep more than one viewpoint in play at the same time. Noting the variety of circumstances assumed in the "you" addressed by the narrators, Krienke sees the novel as providing "an opportunity for its readers to set aside their habitual perspectives and, for a time, experience unfamiliar readerly postures and social roles" (92). This chapter extends the discussion of convalescence beyond its usual association of recovery from debilitating physical illnesses, relating it more closely to active rehabilitation through participation, and is unexpectedly rewarding.

"It seemed scarcely bearable to leave such delightfulness": the young heroine, Mary, and her once-invalid cousin Colin, rehabilitated by companionship and contact with nature. Source: frontispiece, Burnett.

Krienke goes on from this to discuss mental health problems, and the emerging goal of treating sufferers in new and kinder ways. Butler's satire, Erewhon, reveals the harm done by stigmatising and ostracising the mentally ill, and suggests long-time care-giving within society as a better option — even if its course is bound to be uncertain. Again, Krienke shows how the focus on convalescence was shifting towards the more structured project of rehabilitation. Patients were still being sent to convalescent homes, right up into the 1950s, but, as a matter of social provision, the boom in building new ones was over. This in-between era is the one to which Burnett's The Secret Garden belongs. In a wide-ranging chapter entitled "Medicalization of Convalescence in Imperial Settings," she offers another reading of a familiar text by relating it to the complex ideological context of the time, finding in Burnett's treatment of the invalid Colin an effort to "to preserve all the Victorian values of convalescent time, even as it joins these values to ideals of speed, efficiency, and certain health" (147). The trend towards a greater emphasis on rehabilitation was by no means smooth, then, and indeed the ACA (After-Care Association, founded in 1879) struggled under the impact of Frances Galton's ideas on eugenics in the following decades.

More recently, many new factors have influenced our attitudes to illness and recovery. Among them have been the large numbers of soldiers and personnel returning from areas of conflict with both physical and mental traumas; breakthroughs in all areas of medical science; and, most recently, the Covid-19 epidemic with its possibility of Long Covid. Krienke's exploration of how the nineteenth-century novelists represented convalescence (or, in the case of The Moonstone provided some of its functions) has, as she claims, become more relevant than ever. For the literary critic, Krienke's approach offers fresh entries and fresh focuses, which might prompt reassessments of many novels — not just those, like Bleak House and Ruth, in which ill-health plays an especially prominent part. Her valuable research should also be flagged up for Victorianists generally, including those interested in gender, class, medical and colonial history.

Links to related material

- Metropolitan Convalescent Hospital, Walton-on-Thames

- Review of Talia Schaffer's Communities of Care: The Social Ethics of Victorian Fiction

Bibliography

Krienke, Hosanna. Convalescence in the Nineteenth-Century Novel: The Afterlife of Victorian Illness. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2220. Hardback. £75.00. 978 1 108 84484 0

[Illustration source] Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. New York: F. A. Stokes, [1911]. Internet Archive. Contributed by New York Public Library. Web. 24 May 2022.

Created 24 May 2022