hilst he looked around for another position Jerdan did not neglect his pleasures. He was a keen theatre-goer, but sometimes wondered if an “ill-natured fairy” had whispered at his birth, “William, have a taste” (4.382). In his old age he reflected that even more than in art, bad dramatic performances disgusted him to the same extent as immoral actions. That he could claim this when looking back at his life, it is clear that he plainly believed his private life would remain just that – private – but history and biographers seldom respect such hopes. Paradoxically, given the way he led his life in the years to come, Jerdan was a strongly moral man who somehow overlooked his own lapses. In pursuit of pleasures to his ‘taste’, Jerdan took the front seat in the stage-box one evening, to see John Kemble’s gripping performance as Coriolanus. Next day Kemble told Jerdan that he had spotted him in the box, and played the part just for him alone. Jerdan greatly admired the famous tragedian’s comic talents in his private life, recounting how Kemble hid at the close of a dinner party at Freeling’s Hampstead house, whilst he and the other guests departed. It was subsequently reported to him that Kemble reappeared with a bottle of claret from Freeling’s cellar, saying it was “too good for those fellows” and that he and his host could drink it in peace (2.165). Jerdan observed that Kemble was very fond of a bottle or more of wine – a predilection that Jerdan himself was well-known to indulge.

On 23 June 1817 Kemble gave his emotional farewell performance to a crowded theatre, on an excessively hot evening; a few days later the Freemasons’ Tavern (where the Burns Dinner had been held) saw a convivial dinner in his honour attended by many noblemen, and “nearly all the eminent poets, artists and literary men of the metropolis” including Jerdan. The gathering was entertained by one of Campbell’s Odes, and addressed by Talma, the acclaimed French tragedian, whose dramatic delivery Jerdan had strongly criticised in Paris (2.167). Jerdan met Talma more personally at a dinner given by Dr Croly, where the actor spoke of his admiration for Kemble, but thought another major actor, Kean, deficient in intellect and dignity. He demonstrated their differences by declaiming speeches in their individual styles, a performance Jerdan thought original and entertaining.

In the hiatus between employments, Jerdan wrote two books, both parodies of the genre of fiction/travel writing currently popular as France became more familiar to travellers from Britain. His three volume work, each volume of about two hundred and forty pages, entitled Six Weeks in Paris, or, a Cure for the Gallomania, by a late Visitant, was published in September 1817 by J. Johnston of Cheapside and Macredie & Co. of Edinburgh. It purports to be written by an English nobleman. Benjamin Colbert has characterised it as “a cautionary roman-à-clef…arguing that the weak-minded and unwary could easily be drawn into a vortex of vice, tolerated by French moral passivity, yet fatal to English ingenuousness…Jerdan’s novel imitates travel description so well that one suspects it is based on an actual journey…” – which of course it was. Advertisements for the book echo some of the intentions claimed in Jerdan’s Sun “Journal of a Trip to Paris” three years earlier: to educate, warn and advise. Taken from the Preface to the book, and used in advertisements for it, “his Lordship” announces that for the good of his countrymen, emigrating in shoals “to encounter French hatred, deceit, rapacity” the work “is intended as an antidote to the poison of other Publications, teeming with gross exaggerations, fictitious characters and anecdotes, and notoriously false fabrications”. The book is written as a dialogue between two main characters and other occasional participants, who discuss food, religion, the streets, theatre, and all aspects of French life. The tone of the writing is arch and humorous, sometimes biting and sarcastic. The third volume is a love story which is almost a novel in itself. The work was reprinted in 1818, the first time that a work of Jerdan’s enjoyed sufficient popularity to merit a reprint, and more important, the first work of his own imagination, not merely a translation or reporting.

Left: The title-page of Six Weeks in Paris. Right: The title-page of Six Weeks in Paris. Hathi Trust images of a copies in the Libraries of Princeton and Duke Universities. Click on thess image and those below to enlarge them.

He followed this with Six Weeks at Long’s by a late Resident, also in three volumes each of about two hundred and twenty pages, written with Michael Nugent, from material furnished by a military officer who paid them for their literary assistance. Long’s was a hotel in London’s fashionable Bond Street, and Jerdan opened the book with a description of the street, filled with carriages taking occupants to their secret assignations. The style of the book is similar to that of Six Weeks in Paris and of the New Canterbury Tales, also written with Michael Nugent, being a conversation between two or three main characters, notable for irony and wit, including portraits of contemporary literary figures such as Lord Leander (Byron) and also pillorying Beau Brummell. The book falls into the genre of ‘portrait novels’ in Regency satirical fiction, but

pqthese Portraits fail to stress how their satiric attack pertains to issues of general or public interest… [they] have an inconsistency of purpose at their core. On the one hand they profess corrective intent…At the end of Six Weeks at Long’s, its authors indicate that they consider attacks on particular real people a service to the public: ‘When we see them inveigling others into their snares; rendering the weak, wicked; the wealthy, poor; and the innocent flagitious; we should feel ourselves in some measure parties to their atrocity, if we did not endeavour to unmask them.’ [III, 220-221]This was the selling point of the novel: an advertisement in the New Monthly Magazine of 1 April 1817 claimed that:

Works of fiction, we apprehend, are seldom more likely to be really beneficial than when they actually exhibit the portraits of existing characters and scenes with which the world is acquainted. These may perhaps be highly coloured, and rendered in some respects ridiculous through such a vehicle, yet if, in the narrative, the basis of truth be observed, and the prominent features of the actors are faithfully delineated, the cause of virtue will gain by a caricatured castigation of irregularities and persons which the laws cannot reach.

Six Weeks at Long’s reached a third edition, but Jerdan was not proud of it, saying that it was “a personal satire of an order never tolerated by me as a critic” (2.177). His excuse, or reason, was simple: poverty. This book was reviewed in the 5th issue of the Literary Gazette as “a caustic portraiture of ‘noble profligates and honourable dupes’”, a timely connection with Jerdan’s next, and most important career move.

The aggressive and successful publisher Henry Colburn had produced the first issue of the weekly Literary Gazette on 25 January 1817, principally as a way of promoting or “puffing” the books he published, but also to take advantage of the rising literacy and interest in reading amongst the middle classes. It was in a lighter vein and more readable than its forerunners, the ponderous quarterly and monthly reviews. The first nine issues of the Literary Gazette were each of sixteen pages printed in two columns, at a price of one shilling; on the tenth issue Colburn changed its format to three columns per page, at which it remained for many years. The journal was printed by A J Valpy and published by Colburn from 159 Strand, just down the road from number 267, Jerdan’s own building acquired as part of his purchase of The Satirist. Looking back at this venture from a perspective of forty years, Jerdan believed that the country was indebted to Colburn not only for all the subsequent imitators of the new journal, but for the introduction of hitherto new and undiscussed topics into the periodical press. The Literary Gazette became a leading and innovative periodical, and aimed to cover:

Original Correspondence, foreign and domestic; Critical Analyses of New Publications; Varieties on all subjects connected with Polite Literature, such as Discoveries and Improvements, Philosophical Researches, Scientific Inventions, Sketches of Society, Proceedings of Public Bodies; Biographical Memoirs of distinguished persons; Original Letters and Anecdotes of remarkable personages; Essays and Critiques on the Fine Arts; and Miscellaneous Articles on the Drama, Music, and Literary Intelligence: so as to form at the end of the year, a clear and instructive picture of the moral and literary improvement of the times, and a complete, and authentic Chronological Literary Record for general reference. [2.176]

This was a highly ambitious plan, especially for a weekly publication. Hitherto, publications which covered only a part of Colburn’s grand scheme had been published as monthly, or even quarterly, reviews and were aimed at a different, more “up” market and were overtly political. One of the most famous was the Quarterly Review, begun in 1809 by John Murray, the notable London publisher and a man of strong political and religious opinions. He wished to challenge the popularity of the Edinburgh Review, a literary journal whose views were opposed to his own. Sir Walter Scott and George Canning were active supporters of the Quarterly Review, and the publication was edited by William Gifford, a protégé and close associate of Canning’s. The Quarterly Review played a formative role in the criticism of Romantic writers. It was positive about Wordsworth and Scott but vilified the works of Leigh Hunt, Hazlitt, Shelley and Keats. However, the Quarterly Review was a political journal first and foremost, an influential supporter of the Tory party. Depending on which side of the political divide one stood upon, it was considered to be an agent of dark forces, or the disseminator of inside governmental information. For Canning, it was a medium by which he could influence the press. As this last consideration was to become a hot topic between Canning and Jerdan, Canning’s participation in the Quarterly Review is significant. Furthermore, when Jerdan consulted Canning for his advice on taking the editor’s position for the Literary Gazette, Canning counselled him to take the job, but “Avoid politics and polemics”. Jerdan heeded this advice throughout his entire career, and when in any doubt, asked himself “What would Mr Canning’s opinion be?”

In the Spring of 1817 William Blackwood, who was John Murray’s agent in Edinburgh, started the Edinburgh Magazine, shortly changed to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, a monthly publication, of a lighter tone than the Quarterly. Maga as Blackwood nicknamed it when he took over the editorship from the seventh issue, was published in London as well as Edinburgh, and appealed to a similar readership to that of the Literary Gazette. Blackwood’s was joined by John Gibson Lockhart, aged twenty-three (later to be Sir Walter Scott’s son-in-law) and John Wilson, aged thirty-two. They attacked the “Cockney School” of Poetry, criticising the works of Keats, Hazlitt and Leigh Hunt as disreputable and political. Hiding behind the pen-name ‘Z’, Lockhart, whom Blackwood had told to “sharpen his pen”, launched himself at the “Cockneys”, deriding their low birth, their habits, ideologies and free versification, accusing them of “extreme moral depravity” in sarcastic and biting language. These articles continued for several months, echoed by Gifford, editor of the Quarterly who had a grudge against Hunt for mocking him in his “The Feast of the Poets”. Hunt, however, took these vicious attacks as “motivated by political more than literary animus” (Holden 126). Jerdan’s instinct was to agree that the work of the so-called “Cockneys” could not compare with classical, romantic poetry, even with that of Byron, although some of the latter’s work was to cause a storm in the Literary Gazette. Maga became well-known from 1822 for ‘Noctes Ambrosianae’, written by John Wilson under the pen-name Christopher North. The ‘Noctes’ were imaginary discussions about literary and topical subjects, and as time went on, Jerdan became one of those mentioned. The biggest difference between Blackwood’s and the Literary Gazette was that the former published original fiction, often serialised, whereas the Literary Gazette was a paper of review and notices. According to the Waterloo Directory, Blackwood’s was one of the three most important of the nineteenth-century magazines, the others being the New Monthly Magazine and the London Magazine.

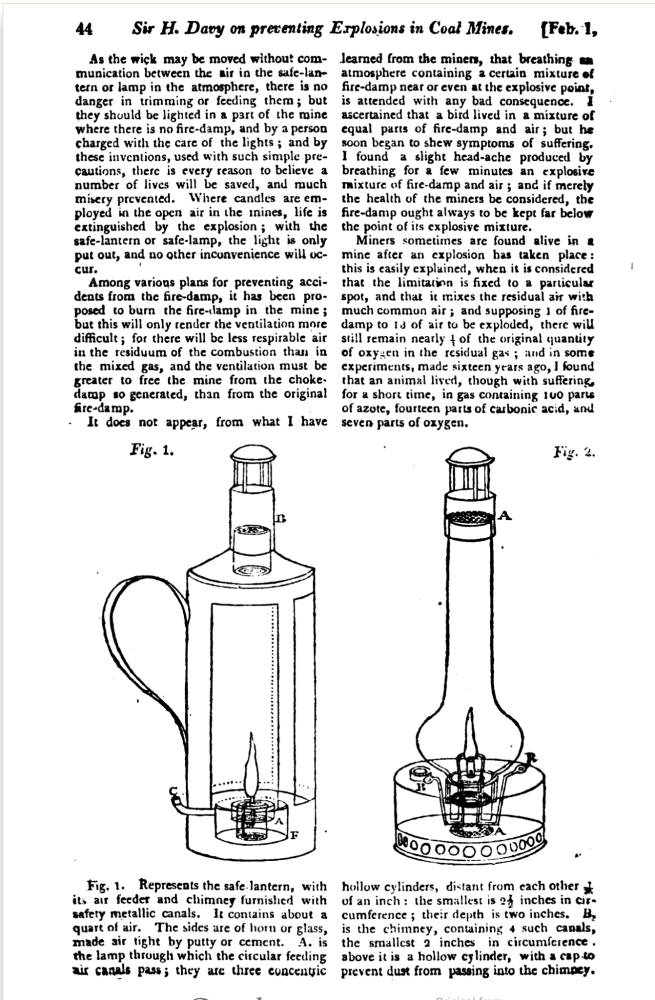

Title-pages, Contents Page, and an Article with an illustration from the New Monthly Magazine: The title-pages of the first issue (1814) and 1816, and the 1826 contents, and “Sir. H. Davey on preventing Explosions in Coal Mines.” Hathi Trust online versions of the magazine in the Libraries of Harvard University and the University of Michigan. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The New Monthly was, like the Literary Gazette, published by Henry Colburn who, together with Frederic Shoberl, started it in early 1814. It was a liberal, anti-Napoleonic journal, with much the same list of departments as Colburn announced for the Literary Gazette, with the addition of political reports and digests. Future editors of the New Monthly were such luminaries as Thomas Campbell, Edward Bulwer Lytton, Theodore Hook and Harrison Ainsworth. As with the Literary Gazette, Colburn saw his publication as historic. The first issue declared that the New Monthly Magazine was to be a “complete record and chronicle of the times”. The London Magazine was published between 1820 and 1829, so was not a contender when Jerdan took up his pen to write for the Literary Gazette for the first time.

Jerdan’s first contribution to the Literary Gazette, a critique on Zuma by Madame de Genlis, a French writer whose work on education influenced Mary Wollstonecraft, appeared in its twenty-fifth issue, on 12 July 1817. The following week he became editor of the journal, a position he held for thirty-four years. With the change of editor came a change of ownership of the Literary Gazette. Jerdan acquired a one-third interest, but whether he paid for this, possibly out of the money he received from the Sun, or whether Colburn gave him the shares as an incentive, is not known. Jerdan’s income from the Literary Gazette depended on its profits, and at this time in his career there is no evidence that he was drawing any salary; the shrewd Colburn would have seen the exchange of one-third of the shares as a good investment to keep his new editor on board, loyal and hard-working. Colburn himself held one-third, and the final third was held by Pinnock and Maunder, publishers of the Literary Gazette who presumably paid Colburn for their share, reimbursing him for his investment in the new paper.

Left two: The first issue of The Literary Gazette in which Jerdan published an article, and the page with the review. Right: The 1834 Title-page. Hathi Trust online versions of the magazine in the University of Michigan Library.

St Clement Danes, Strand. Nathaniel Sparks, R.E.

Under Jerdan’s editorship the offices of the Literary Gazette were moved to the building he owned at 267 Strand, opposite St Clement Danes church. Jerdan grew to dislike the monotonous chime of the bells, which made him feel dull and melancholy. At one end of the Strand was Waterloo Bridge which had just been opened in June 1817. The architect Rennie had modelled the bridge on the one he had built in 1800-1803 in Jerdan’s home town of Kelso, a visual link between his London working life and his old home. As a consequence of moving the Literary Gazette into the building which had caused him so much aggravation and financial loss, Jerdan sold the building to Pinnock and Maunder. The men were brothers-in-law, but of very different temperament. Maunder was reliable and steady, but Pinnock was volatile and restless, perpetually dissatisfied. His flawed personality was to have an adverse effect on Jerdan and the Literary Gazette.

However, at the outset, the new job was a godsend to Jerdan. He did not feel himself to be a natural writer, “the dignity and stilts of authorship never suited me. If I tried to write grand or fine I was sure to fail” (2.174). However, he admitted to an ability to write clearly and intelligibly, a talent crucial for the vast amount of comment and review that he undertook over the ensuing decades. He was fortunate in the timing of his new venture: Scott’s Waverley novels had appeared by 1817, whetting the middle classes’ appetite for literature, and Byron had raised popular interest in poetry; the arts were burgeoning in the absence of war, the world had opened up to travellers who wrote copiously of their adventures, theatre was overflowing with talented actors and many productions, shows and exhibitions were all the rage. The reading public was expanding rapidly, and with the rise of literacy came demand for ever-more and cheap books. The newly literate needed guidance as to taste and quality, and Jerdan’s Literary Gazette was ideally placed to cater for their needs. Technology developed to facilitate and speed printing, as lithography became used more widely, an invention of which the Literary Gazette was among the first to take advantage. Thus everything conspired to promote the aims of the Literary Gazette in a rich and fulfilling way. For the affable Jerdan, it was a perfect vehicle, giving him an entrée into many different societies and groups, who were keen to nurture his interest in order to further their own. It was a busy world, and Jerdan was happy to be among those “stirring”.

The importance of the Literary Gazette and the vital part Jerdan was to play as its editor, were recalled years later by Samuel Carter Hall, an acquaintance but no friend of Jerdan’s, whose opinion is therefore more valuable:

It would be difficult now to comprehend the immense power exercised by the Literary Gazette…between 1820 and 1840. A laudatory review there was almost certain to sell an edition of a book, and an author’s fame was established when he had obtained the praise of the journal. People do not, perhaps, think more for themselves now than they did then; but the hands that bestowed the laurels were at that time few…for a quarter of a century there was but one who was accepted as an ‘authority’. The Gazette stood alone as the arbiter of fate, literary and artistic. [235]

Over the period Jerdan edited the Literary Gazette it contained, exclusive of advertisements, “roughly 25,000 words per issue, a million and a quarter per year, totalling over 42 million words – the vast majority written by Jerdan himself” (Pyle 8). A massive task lay ahead, one that Jerdan surely relished.

Among his first tasks was to assemble a core group of contributors, including “laborious Lloyd” (Hannibal Evans Lloyd) of the Foreign Post Office, who collected and translated foreign intelligence, and had probably edited the first few numbers of the Literary Gazette before Jerdan took over. There was also Thomasina Ross, daughter of a Times reporter, a translator who had assisted Lloyd (Pyle 40). More well-known and prolific contributors were the Rev. Dr. Croly, the artist Richard Dagley, both of whom became lifelong friends to Jerdan, and others whose names were famous in their day. Jerdan valued these assistants, but at the beginning, he undertook the bulk of the work himself:

In my capacity I was omnivorous – at all in the ring – and produced hebdomadally [weekly], Reviews, Criticisms of the Arts and Drama, jeux d’esprit in prose and in verse; and in truth, played every part, as Bottom, the weaver, wished to do; and it might be only from the good luck of having, in reality, several able coadjutors (though I announced publicly I had them), that the paper did not sink under my manning, in addition to my pilotage. [2.179]

One scholar has interpreted Jerdan’s statement to mean that he wrote the bulk of the Literary Gazette himself, being too penurious to pay others, and that this remained the case throughout his editorship (Duncan, iii, pp. 7, 16, 38-40). An opposing view, taken by a later scholar, suggests that Jerdan meant that he was involved in the writing of some of many parts of the Gazette; that there is evidence to corroborate the interpretation that he employed many contributors (Pyle 129). He claimed, in a response to an attack by Hazlitt in the Edinburgh Review, that a dozen different writers had contributed to the last number of the Gazette (23 August 1823, 538). Almost no evidence is available concerning rates paid to Literary Gazette contributors, largely because of Jerdan’s self-confessed carelessness in keeping records, and because one of his later partners, Longman & Co., saw to the business side of the journal. Only a comment from Gerald Griffin referring to “a liberal remuneration – a guinea a page”, and indications that Pyne received three to four pounds for each ‘Wine and Walnuts’ sketch (averaging less than three pages) give any clear idea of early Literary Gazette payments.

Under his new editorship, circulation of the Literary Gazette seemed to be turning “…Up, and but for a few incidental or accidental crosses, would have been Up-per” (2.178). There is the ubiquitous Jerdan “but” again: such “crosses” were the integral and repeating pattern of Jerdan’s life: his poor health (and his unwillingness) had impeded his legal studies, The Satirist readers had not welcomed his changes to a more morally respectable journal, and Taylor had blighted his partnership in the Sun.

At the start of his connection with the Literary Gazette, however, all was hopeful. The publisher, Henry Colburn, already had a reputation as an aggressive promoter of his books; he was an entrepreneur through and through, seemingly more interested in the bottom line of accounts than in the promotion of literature. According to The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction, Colburn’s origins were mysterious, rumours suggesting that he was the illegitimate son of the Duke of York, or of Lord Lansdowne. He began his life in the book trade whilst still a youth, and by 1808 was at the British and Foreign Library in Conduit Street, London, publishing books under his own name. He soon became sole proprietor. Within weeks of starting the Literary Gazette in 1817 Colburn employed William Jerdan as editor, but his mercantile interests remained foremost, a fact which Jerdan overlooked at his peril. Colburn’s relentless promotion of his books and Jerdan’s desire for a journal of objective literary review were a potent recipe for a clash. Indeed the subject of “puffery” or in-house advertising, became one that, within a few years, created strife for the participants (and a minor industry for subsequent literary researchers).

Hopeless as he was at record-keeping, Jerdan related that he had found a notebook stating that “income from the Literary Gazette in its early days (in a January, but not stating which year, a typical Jerdan omission), was in the order of £5, £3, £2 and £4 3s 6d, totalling £14 3s 6d. Succeeding months were “worse for balances” (3.11). Things were quickly to improve.

Through a friend he had acquired a manuscript of Captain Tuckey’s Voyage to the Congo, later published as a book by John Murray in 1818. This account appeared weekly in the Literary Gazette from its thirtieth issue (16 August 1817) and proved unexpectedly popular. This surprising upward turn of events bore out Jerdan’s principle of journalistic prosperity: “Sleeping will not do”, one must be ever alert to opportunity. According to him, sales of the journal rose by over five hundred, equal to about one thousand pounds a year, and improved Jerdan’s expectations of a share in profits (2.187). However, trouble came in the shape of Sir John Barrow, Secretary of the Admiralty, who told him Tuckey’s had been a government expedition and details had been published that should not have been made public. Barrow blamed a particular officer, but Jerdan protested that his informant, whose identity he did not know at that time, should not be castigated. He and Barrow quarrelled, and although Jerdan was soon able to prove that the accused officer was innocent, the culprit being some lowly clerk, relations were cool for a while. Moreover, the Literary Gazette publication of Tuckey’s manuscript anticipated Murray’s book publication by some months, causing the famous publisher to resent Jerdan’s pre-emption.

During his first few months in charge, Jerdan widened his circle of contributors to the Literary Gazette, to include the poet George Crabbe (admired by Byron), writers Miss Mitford and Thomas Gaspey, artists John Preston Neale and Henry Howard RA, and the architect William Wilkins (who, to Jerdan’s disgust, was later to design the National Gallery). Jerdan was especially proud of the Literary Gazette’s coverage of Fine Arts, so dear to him, and hitherto neglected by the majority of the press. He cultivated acquaintance with the “leading men of the period”, and his own social standing rose as a consequence. Success breeds success, and he later claimed that “the present highly improved system of our periodical literature may, in great measure, be traced and attributed to the pioneering of so humble an individual as myself” (2.192). That he did indeed play a major role is evident, but it would have been more dignified, perhaps, to let others blow his trumpet for him.

By the summer of 1817 the Jerdan family had moved house again, this time to Rose Cottage, Old Brompton. He quickly found himself giving evidence at the Old Bailey, following the arrest by a watchman of an eighteen-year old man, for stealing three live tame geese from his coach house, and seven eggs value sixpence from his hen house. According to Proceedings of the Old Bailey, the culprit was found guilty, and transported for seven years (ref. T18170917-252). Whilst his “quiet and pretty residence” was being made ready, the family had temporarily stayed in Little Chelsea, neighbours to the Princess of Condé, daughter of the murdered King of France, Louis XVI. Jerdan called upon her several times, mostly on local matters, and noted her thick-soled boots and dress no better than a milkmaid’s. (Some years later, Jerdan was riding in a carriage with the President of France, Louis Napoleon, and pointed out to him the modest house where his kinswoman had lived. This greatly moved the President, who referred to it on many subsequent meetings with Jerdan.)

However, at the time, Jerdan was not hobnobbing with Presidents. His own finances were in a parlous state. During his turbulent time at the Sun he had incurred debts, and these, coupled with the failure of Whitehead’s Bank where he had entrusted his savings, conspired to throw him “behind-hand with the world”. The money he received from the Sun was not sufficient to clear his debts and pay his current expenses, and it was to be three years before the Literary Gazette became profitable enough to provide even the most basic subsistence. To add insult to injury, he received a bill for eighty-eight pounds from his lawyers for the Sun litigation. He brooded that he was so encumbered by debts, he would have been wiser to appear in the London Gazette (which listed bankruptcies) rather than the Literary Gazette, a sombre joke which was to prove prophetic. From this period on, interest on his debts accumulated and he paid “thirty or forty shillings for every pound and got plentifully belied and abused by my unsatiated plunderers” (2.196). In an effort to improve his resources he applied for some kind of government employment, but was turned down.

Somehow he kept his ironical sense of humour. In the Literary Gazette of August 1817 he published a letter he had written addressed to “My dearest Friend”, i.e. himself. “Why am I writing this?” he asked his correspondent, “when I could so easily speak to you in person.” He answered that he didn’t begrudge the postage, and believed a formal communication would get his attention: taking on the challenge of the Literary Gazette requires

the strength of Hercules, united to the talents of the admirable Crichton, and the calculating powers of the American boy, would not suffice for the execution of such a task. I am afraid you have over-rated your capabilities…Mr Editor! I am afraid you have not well considered either your difficulties or your dangers…You review new books forsooth; every censure makes an author and his partisans your foes. You criticise the drama; …You will be pilloried in a farce, caricatured by Matthews and transfixed by as many thousand shafts of ridicule as the wit of modern dramatic writers can supply. You also criticise the arts: artists are even more irritable …If your literary intelligence is not a string of puffs, publishers will abominate as much as authors abhor you…

His “letter” went on to tell the tale of a dog so beset by a swarm of bees that despite the writer’s success in freeing him, the pain was so great that the dog died – he left it to himself to connect the analogy of this tale to his own life. It is evident that from the outset of his editorship of the Literary Gazette, Jerdan was sensitive to the dangerous waters he swam in. Not only would writers and artists resent a bad review, but publishers whose books he did not actively promote would despise him. Censuring society would deprive him of a welcome everywhere. It is a wonder that he had the courage to proceed at all.

At the height of popularity of the ‘Gothic novel’, the Literary Gazette reviewed Thomas Love Peacock’s Nightmare Abbey, which satirised the vogue. Peacock’s barbs were directed at Byron and Coleridge, in the guise of his two main characters, the first of whom Jerdan strongly disapproved because of his perceived immorality. However, he seemed to have missed Peacock’s point, reviewing the novel as “executed with greater license than nature and with more humour than wit”, puzzling over the novel as not fitting into the known genres of “romances, novels, tales, nor treatises, but a mixture of all these combined.” Jerdan has been accused of being “hostile to satire” (Duncan 179), an accusation perhaps based on his failed attempt to rid The Satirist when he bought the paper, of its more scurrilous aspect, but a view which ignores his satirical verse of “Vox et Praterea Nihil” and the “British Eclogue” of a few years earlier. Jerdan was to pen several more pieces of satirical work over the years, although never with the aim of cruelty that satire often implies. The Literary Gazette ignored Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey published in the same year, which, with hindsight, was an error of judgment on Jerdan’s part.

Reviews in the Literary Gazette were not signed, and it is only by recognising his style of writing that Jerdan’s own contributions can be identified. No marked up office copy has been found, an omission in keeping with Jerdan’s own often repeated complaint that he was not a record-keeper. Some contributors can be identified by letters that have been found, but in the first three years of Jerdan’s editorship it is likely that the majority of literary reviews came from his own pen. And even if they were by someone else, he had to authorise them. Anonymity was deliberate, and Jerdan endeavoured to give the Literary Gazette its own identity, rather than as a vehicle for individual writers. He made this clear:

Some confusion having arisen in consequence of Gentlemen who contribute to the various departments of this journal, as well as others being addressed as the organs of communication, or as responsible for its contents, we beg leave to refer to our Imprint for the proper mode of communication, and to say, that it is uncandid and erroneous to fix upon Individuals as the Writers of Articles, in a publication which boasts a little Republic of Literature. [26 July 1817]

An exception to his rule was his chief art critic, William Paulet Carey, who was already on the staff of the Gazette. A later art critic, revealed by his obituary in the paper of January 1842 was Walter Henry Watts, who had served for over twenty years. Occasionally Jerdan wrote an original piece, and identified one of these in his Autobiography, although in the Literary Gazette it was signed an unlikely “F. Munchausen Pinto”. This piece was a long and amusing story about being thrown from a carriage, concussed, and dreaming of a visit to the Enneabionians, an unknown race in the interior of New Holland, a race where the people had ten lips and nine lives. A diagram was included showing how, as each life was lost, another lip opened. This story is reminiscent of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and is, similarly, a political satire in the style of travel writing so popular at the time. Jerdan also satirised the pomposity of anthropologists and other scholars: the traveller told an Enneabionian philosopher of the English phrase used when someone is sad, that he is “down in the mouth”, which provoked a two volume treatise proving that Great Britain was an Enneabionian colony. Politics too are shown as pointless: once actions are taken, politicians are neglected – literature is the only comfort. The moral of the story was that “the poor wretch with only one life is just as happy as the Enneabionian with nine” (2.213).

Jerdan also indulged in a sci-fi fantasy, with a story wherein the narrator met a mermaid who could see into the future. Unfortunately the narrator was shot whilst she was divulging her experiences to him, and on recovering, he wrote down all that he could remember about 1820, only three years ahead. The world had turned topsy-turvy and no aspect of political or cultural life escaped Jerdan’s ascerbic pen. He even wrote, jokingly, of a tunnel from Dover to Calais, and a canal to carry the Nile avoiding cataracts. These were not the only prophetic ideas in this piece: he also suggested that “The greatest improvement in politics seems to be the system of legislating entirely through the medium of newspapers”, an idea he obviously thought silly, but it still to this day a topic of debate.

Robert Southey. Frontispiece of the first volume of New Monthly Magazine (1814). From a Hathi Trust image of a copy in the University of Michigan Library.

Jerdan’s inversions and criticisms of the social and political mores of his times appear in stories such as these last two examples, more than likely as a safer, less confrontational way to bring them to his readers’ attention than straightforward journalism. His light and superficially humorous tone takes the sting out of his barbs, and would thus not be overtly offensive to his powerful and influential friends such as Canning. A more cogent reason for cloaking satire and criticism in humour was what has been called “the most decisive single event in shaping the reading of the romantic period” (St. Clair 216). In the 1790s, at the age of nineteen, Robert Southey had written a political verse drama, ‘Wat Tyler’. In 1817 a publisher, Sharwood, without asking Southey’s permission, printed and sold copies of his manuscript. In the interim Southey had become Poet Laureate, and had changed his views. He believed that his republican work, which (like Jerdan’s stories) “ridiculed royal extravagance, oppressive taxes, aggressive wards and cynical churchmen, would encourage unrest and revolution” and the publisher could be prosecuted for sedition. Southey asked for an injunction against the publishing of this work, and damages for breach of copyright, of which he believed he was the owner. His case fell apart because the Lord Chancellor said it was the text itself which was not lawful, and that Southey would need to bring a case for seditious libel against the printer or publisher. This created a vacuum into which pirate publishers jumped, selling 60,000 cheap copies, and the text remained in print for decades. Jerdan would be extremely wary of publishing anything, least of all his own work, against which a charge of sedition could be brought.

The first year of the Literary Gazette came to an end on an optimistic note: circulation had risen, largely thanks to the serialisation of Tuckey’s Voyage to the Congo, the number and quality of Jerdan’s contributors had widened and the Literary Gazette was being read and spoken of by “the superior classes of the educated and intelligent who were addicted to literature” (2.234). Jerdan reported that its first year receipts were £109 and the paper sold almost one thousand stamped, and two hundred and fifty unstamped copies (The stamp tax was payable on newspapers and periodicals, and was required if these were sent by post; unstamped copies were illegal until after the “wars” on this tax in the 1830s, resulting in the law’s repeal in 1836). It was a solid foundation from which Jerdan could move forward to shape the Literary Gazette into an influential guide to contemporary literature and culture.

As his journal rose in popularity, Jerdan became ever more deluged with submissions of prose and verse from would-be contributors, requesting that their work should be favourably ‘noticed’ in the pages of the Literary Gazette. Such importunings, he claimed, did not influence his decisions whether to review or to ignore a work, whether to praise or criticise it. The literary worth of the work was the sole deciding factor. If he could not praise, then censure was to be mild; defects pointed out “in a friendly manner”, and severity never exercised, unless “the publication gave great offence, by its immoral and dangerous tendencies” (3.11). Although at the time literary reviews were believed to be highly influential on opinions and sales, this may not quite be the case, for as A. A. Watts points out, many books were published long before reviews appeared, selling well despite this (189). Byron’s Childe Harold was an example. Watts noted that there was “no correlation between reviews, reputations and sales, or between contemporary and later reputation.”

The Literary Gazette stayed faithful to the promotion of fine arts and literature and was the means of introducing to the public many whose names became famous in their time. Jerdan consulted friends for their advice, and some offered to assist on a voluntary basis for the time being. Jerdan himself was very keen on poetry, a preference inculcated in his late eighteenth-century education, and one that he failed to see was not shared by the public as the century proceeded into the decades of the 1830s and 1840s. At the outset, the Literary Gazette was “the wet nurse to bards” (2.232). An issue in November 1817 was the first publication where Bryan Waller Proctor’s work appeared, (better known under his pen-name of Barry Cornwall). The Literary Gazette also featured several female poets. Some were already well-known, such as Mrs Rolls, Barbara Hofland and Felicia Hemans. The four daughters of Jerdan’s old lamented friend Begbie also wrote for the Literary Gazette, as did the sisters of the Rev. Dr Croly, himself a long-time aide to Jerdan and husband to one of Begbie’s daughters. The poets helped to establish the reputation of the paper in those early days when, as Jerdan wryly observed, “poetry was not a drug but a public pleasure!” (3.277). It was indeed a poetical era, boasting Campbell, Scott, Byron, Shelley, Southey, Wordsworth, Coleridge and, their equal in Jerdan’s eyes, but forgotten today, George Croly. The Literary Gazette of 1818 carried several of what Jerdan called “fine compositions” by Croly, including ‘Paris in 1815’. Jerdan usually supported Sir Walter Scott’s work; he was a Tory and a Scotsman and a phenomenally successful novelist. However, in a February issue of the Literary Gazette Jerdan oddly observed, “we do not like Sir Walter’s gratuitous servility, we like Lord Byron’s preposterous liberalism little better”. Thinking back to this period of the Literary Gazette, Jerdan acknowledged that many of the minor poets were forgotten forty years later, but that “The greater and smaller wheels are all necessary to the wonderful machine” (2.235).

Poetry was therefore a vital component of the Literary Gazette but there were other circumstances which also raised the journal’s reputation. When the Archdukes of Austria visited the printing press of the Literary Gazette’s typographer, Bensley, Jerdan was asked to act as translator. He modestly said his French was indifferent and he hardly knew the technical names of the press in English, but their Imperial Highnesses were impressed and ordered that the Literary Gazette be delivered to them regularly, an act which increased its fame and circulation in Germany. The Archdukes wrote about their tour of England, and this was translated for the Literary Gazette by the indefatigable Lloyd of the Foreign Post Office together with Miss Ross. Publication of the Archdukes’ Remarks boosted the reputation of the Literary Gazette, causing Jerdan to muse “On such accidents do many of the important events of literary success, and even of life, often take their hue” (2.215).

A feature which boosted the circulation of the Literary Gazette was the commencement of a series called “The Hermit in London”, a spin-off from Jerdan’s translation of A Hermit in Paris a few years earlier. The author was a Captain Macdonough, who was retired on half pay, and penned over twenty essays in this series of “smart and graphic sketches of society”. Colburn initiated the feature, begun in Issue No. 77 on 11July 1818, as one “written by a person of distinguished rank and title”. Jerdan was more impressed that the author was keenly observant, and drew “original pictures from life…without trenching upon private matters or personalities” (2.238). Colburn had also arranged with Stendhal to supply Paris correspondence to the Literary Gazette and this arrangement remained in place until Jerdan appeared to end it in March 1822. In the interim he had severely edited Stendhal’s letters when he considered them too long or too political. The Frenchman continued to write for the New Monthly Magazine after Jerdan had dispensed with his services (Pyle 127).

There was always a certain amount of mutual back-scratching with other journals. Jerdan welcomed an opportunity to receive Blackwood's Maga. In a letter of 15 April 1818 to P. G. Patmore, a correspondent from the rival house, Jerdan told him:

I was much pleased with the one or two numbers which I purchased at Murray’s, and would have completed the set, but you can well form an idea of the heavy expense I am at for periodicals, taking as I do most of the French, German and Italian works of literary interest and a great number of the daily, weekly, monthly and quarterly productions of our own prolific island. I have the Edinburgh Magazine (Constable’s) sent regularly and without charge from Longman’s; and have quoted both that and Blackwood’s in the Literary Gazette. Of course, any notice of the L.G. in the Magazine would be advantageous, and I trust it is seldom altogether destitute of interesting matter for quotation. I make it an invariable rule to give honour where honour is due, and never fail to mention the source of any extract I take. This is, in my opinion, the only candid and honourable way of availing ourselves of the fruits of contemporary labour. [Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. Let. e.86 f7]

This glimpse of the sheer volume of material that Jerdan had to scan each and every week, to ensure that his journal was never behind the competition, and preferably well in advance of it, shows that his reading list was formidable. His letter also declared that the circulation of the Literary Gazette rose every week, and that in the previous six months sales had risen by six hundred copies.

In return for citing the source of his quotations from Blackwood’s and other publications, Jerdan sent Blackwood a copy of Barry Cornwall’s poems in May 1819, gently suggesting a notice by being “not injudicious enough to endeavour, did I wish, to warp your judgment…I greatly admire my friend’s poetical genius” (10 May 1819, National Library of Scotland, 4004/163-4). A couple of weeks later he thanked Blackwood for his “attentions” to Barry Cornwall, and warned him that a letter from Paris which Blackwood’s had printed was not original, but a translation, and gave him the source. Jerdan’s sense of honour on professional matters was strong; here he was being helpful, not spiteful, in pointing out an error to his rival editor and friend.

His promotion of Bryan Waller Procter (Barry Cornwall) was one of several examples of Jerdan nurturing a young talent. In his own Literary Recollections Proctor made no mention of his debt to Jerdan or the Literary Gazette despite the fact that Jerdan had discovered him and at least once a month for three years, published some of his work, either poetry or short prose pieces. In May Jerdan took the opportunity, when reviewing Procter’s Dramatic Scenes and other Poems, to set out his own views on the current state of poetry, and what he considered should be its aims. His statement defended romantic values in opposition to neo-classical, and displayed the schism between his late-eighteenth century upbringing and the modern taste for change in the aftermath of years of war. As Editor of the Literary Gazette Jerdan was exceptionally well placed to deliver his opinion to a wide reading public. His opinion was relevant both to his journal and as an explanation of what was to follow in his private life. His language was, as usual, prolix and flowery, but the content is of vital interest in understanding the nature of the man himself, a man who was in an almost unrivalled position to influence large numbers of readers:

The greatest literary revolution, which has turned the taste of England from foreign imitation to her original treasures, is now familiar to our readers. Whatever might have been the cause, whether the passion for novelty, the long exclusion of Continental intercourse, or the vigour of the public mind, first exhibited by the struggle of war, and then exalted by the glories of unexampled victory, the effect has been produced with a fulness and a power that seem to place us beyond the possibility of a relapse. It is forbidden for a writer henceforth to establish a distinguished character upon the minor ingenuity of his weapons; no epigrammatic and pointed turns of wit, no keen and satiric employment of phrase, will be suffered to enter into the lists where the high prize of fame is to be won. A nobler and more lofty stature must be exhibited in that combat; and with all the artificial habilliments of the day flung aside, the prize must be toiled for by the vigour of naked heroic nature. The simplicity of this revived taste is at once a pledge of its truth and of its permanence. Imagination is the Sun of Poetry, all substitutions for that perpetual and sublime splendour must disturb or dim the true colours of nature; from the passing cloud to the total eclipse, there is a gradual loss of beauty in the sphere of vision; and when the full darkness comes at last, no earthly fabricated fire can supply the security, the expansion, and the glory of the great centre of the system. All the authorship of England has felt this change shooting down through its parts; the hasty writing of our public journals displays a general vigour, that twenty years ago would have been considered as the privilege only of the highest names. But the change has been still more obvious in the hallowed garden of poetry; the richness of the oil had slept, but was not dead; and the moment it had ceased to be cut into serpentines and trodden into dust by the capricious and tasteless of the world, its old luxuriousness rose up, and the first flower from above showed us what blooms and beauty might yet expand for our delight and wisdom. Fashion was the guide of the last age, Nature is the guide of the present and our progress must be from grandeur to grandeur; a keener sense of passion, a purer simplicity, a more comprehensive vision of nature, a more majestic, solemn and sacred love of all things lovely, will be wrought upon us in that upward flight, and, like the translated Prophet, the spirit be made sublime its ascent to receive the palm of immortality. [Literary Gazette (22 May 1819): 321]

This was high-flown language indeed to set out his vision of the return of the kind of poetry he was brought up on, the kind he did not want to see change. In his own verse, which he sometimes included in his journal, taking advantage of his position, he was not quite so ambitious, although he maintained that being a writer himself, he was better able to judge the efforts of others. One of his verses was uncharacteristically serious. “Night Dreams – Life Dreams!” spoke of the submerging of love, of poverty making life hell, of death and disease and the failure of friends to succour the needy (31 October 1818: 698). The poem was composed of Spenserians, with “the personifications of Disease and Poverty looking back to eighteenth century models, though the poem eschews allegory for more naturalistic effects” (English Poetry 1579-1830). Such dark thoughts did not often surface in Jerdan’s writing, which was more likely to be a parody on a Greek verse, or a joke about pimples. He wrote “Night Dreams” at a time when he himself felt insecure and his resources insufficient for his needs, despite the upward trend of his journal.

Insecurity was hardly surprising in this year of the Peterloo Massacre, when armed troops stormed a protest meeting in Manchester killing eleven people and injuring four hundred. Protests were inevitable – the government had clamped down on press freedoms, increased censorship and had not furthered the cause of Catholic emancipation or parliamentary reform. Demonstrations in London followed in September. Jerdan’s personal insecurity was much closer to home, in the behaviour of the volatile Pinnock, under whose roof, with Maunder, the Literary Gazette was produced. The brothers-in-law were co-partners in the Literary Gazette with Colburn and Jerdan. They had a highly successful and lucrative business publishing catechisms and short histories for children, and their provincial contacts were beneficial to the circulation of the Literary Gazette. But Pinnock wanted more than this, and dived headfirst into business ventures he knew nothing about. One such, where he thought he could make a fortune, was to corner the market in veneers, and the manufacture of pianofortes. He thought he could create a monopoly and thereby name his own price to all other musical-instrument makers who needed his material. This venture, and other schemes he tried, all failed. These distractions, and Pinnock’s lack of attention to the accounts of the Literary Gazette were a recipe for disaster. Jerdan’s income became more precarious than usual, and by the end of 1819, although circulation had increased considerably, sales were only fifty pounds more than the previous year’s one hundred and nine pounds. The cost of newspapers and magazines was well above what the working man could afford, and the reading classes, that is the upper and more substantial middle classes, numbered about one and a half million; this was Jerdan’s target market so he still had far to go.

To supplement his income Jerdan found time to write leaders for the North Staffordshire Potteries Gazette, and essays for the Chelmsford Chronicle. He also saw two books through the press for John Murray, who paid him seventy-five pounds for Fitzclarence’s Journey from India to England. Fitzclarence, later Lord Munster, remained Jerdan’s lifelong friend. Colonel Hippesley’s Voyage to the Orinoko earned him fifty pounds and Jerdan also negotiated the copyright to Hippesley for one hundred pounds, receiving a “handsome bronze inkstand” from the author as a token of gratitude (Jerdan’s negotiating Hippesley’s copyright and assisting Murray is one of the first times Jerdan acted as agent for an author, a role he played frequently in subsequent years, and is discussed later.) In Men I Have Known Jerdan identified himself as the author of an article “Origin of the Pindaries” in the January 1818 Quarterly Review (308), perhaps another income-raising attempt; he was aided in this venture by material from Sir John Malcolm. All this extra work was necessary to keep the wolf from the door, and, as Jerdan said, to stop Rose Cottage becoming Bleak House. His efforts were not enough to prevent him having to sell his horse, and after only a year or so, in May 1819, move from Rose Cottage to 7 Upper Queens Buildings, facing the Brompton Road (dated from a letter sent to him at that address). According to the Survey of London Queens Buildings was home mainly to tradesmen and craftsmen (vol. 41), and the move must have been a blow to the ambitious and social-climbing editor.

Jerdan and Frances’ fifth child had arrived on 2 August 1818 and, a year later was christened George Canning Jerdan, together with his sister Mary aged five, and brother William Freeling, aged three (Bishops Transcripts, St. Mary Abbott, Kensington. DL/T/47/23). That such an eminent person as Canning agreed to be godfather and give his name to Jerdan’s son is surely evidence that he held Jerdan in high regard. Canning even went himself to St Mary Abbots Church, Kensington, to ensure that the child’s baptismal name was properly registered in the record book. The minister officiating at this multiple christening was Jerdan’s close friend and poetical colleague, the Rev. George Croly.

As well as trying to meet the demands of his family and keep up with all the work entailed in running a weekly journal, Jerdan embarked upon an activity close to his heart: the succour of the needy author. The Literary Fund had been established by the Rev. David Williams in 1790 (Smith). Williams had initially hoped for it to be a Royal Society of Authors, to include a college for the sons of authors, with a library and archive. This proved too ambitious a plan, and he abandoned these extensions, concentrating instead on the Literary Fund itself. In addition to being one of its first subscribers the Prince Regent had, in 1806, given the Fund a house in Soho to use as offices. Its purpose was to relieve authors in distress; the list of distinguished writers who benefited from it is impressive, and includes Coleridge and Chateaubriand. Several were beneficiaries as a direct result of Jerdan’s intercession, which often kept the writer out of debtor’s prison. The Fund also helped widows and orphans of writers whose death left their families destitute. In 1842 the Fund was allowed to add ‘Royal’ to its title. Jerdan was introduced to the Literary Fund by James Christie, and was already involved in its work in 1818, when he decided that the President of the day, the Duke of Somerset, was too slow and lethargic to be effective. Jerdan wrote about the Fund, to stir things up and get it operational again. He found a powerful ally in Sir Benjamin Hobhouse, a Whig MP and social reformer. Within a year £1157 had been raised, of which £820 went to the relief of unfortunate authors.

By the time Jerdan began his involvement with the Literary Fund it had become an established charity with over four hundred subscribers, including peers and baronets. London’s most eminent publishers, Longman, Cadell and Murray, also supported it. However, few notable writers were subscribers and Southey was the first of several to attack the Literary Fund on the grounds that it “distributed a pittance which was almost useless and did so with ‘despicable ostentation of patronage’ (Cross, 14). Scott declined to subscribe, explaining that he preferred to give money directly to those in need rather than to a general fund. Such personal assistance was practised by other leading authors. The case of Coleridge highlights the point: “When the Literary Fund gave Coleridge £30 in February 1816 out of their income of about £2000 per annum and stocks worth nearly £17,000, Byron sent him £100 ‘being at a time when I could not command £150 in the world’” (Cross, 14). Fortunately for the myriad of impoverished writers who were not known to such exalted beings, and could not expect help from such quarters, but were in dire want of any funding they could get, Jerdan took a different view and gave much energy to his work on behalf of the Literary Fund, recalling that it was “an object of my zealous and ceaseless exertion” (4.34).

The Literary Fund held fund-raising events, and most importantly an annual dinner designed to raise public awareness of the Fund and to attract new subscribers. To Christie’s displeasure, the poet Fitzgerald traditionally gave a recital of his verse at almost every Anniversary Dinner. His theme was frequently the wrongs and sufferings of the literary classes and Jerdan thought one example worth repeating for posterity, even though the poet was so often ridiculed:

But of all wants with which mankind is curst,

The accomplished Scholar’s are, by far, the worst;

For generous pride compels him to control

And hide the worm that gnaws his very soul.

Though Fortune in her gifts to him is blind,

Nature bestows nobility of mind,

That makes him rather endless ills endure,

Than seek from meanness a degraded cure!

Yet from his unrequited labours flow

Half we enjoy, and almost all we know. [2.237]

These sentiments, and the Literary Fund Anniversary Dinners were of great importance to Jerdan whose sympathy, pity and practical assistance to struggling writers was one of his most enduring and endearing characteristics.

Despite, or perhaps because of, his strict Tory upbringing and beliefs, Jerdan always tried to reform where he saw injustice. His reforming zeal led him to write often in favour of an Equitable Trade Society “for the adjustment of disputed accounts, the prevention of law suits and the benefit of commercial and trading interests” (2.249). This plan, too, fell on deaf ears. Another of his projects, he claimed, was to campaign for the establishment of free drawing and design schools throughout the kingdom, to encourage fine art. Although this did not happen at the time, Jerdan lived long enough to see some moves towards such schools in his old age. He also worked fervently – he said he was the first to make a public outcry – against cruelty to animals. This too, he saw come to take a positive form in later years.

In the interests of reporting for the Literary Gazette and also for his own insatiable curiosity, Jerdan began to attend the many scientific and learned institutions then being established. Publication of their proceedings in his journal was, he felt, his contribution to “remove the bushel from over the candle, so that its light might be diffused over the land” (2.249).

In the Spring of 1818 an event occurred which meant much to Jerdan: an acquaintance, Sir John Leicester, opened to the public his Gallery of Native Artists in Hill Street, Berkeley Square, in London. He was the first great patron of British Art, an avid collector, with the intention of establishing a National Gallery of British Art. Admission was free to all, an innovation in England where hitherto staff at country houses with art collections were given gratuities for showing visitors around. The Literary Gazette took up this topic, when it printed a letter headed ‘Admission of the lower orders to Public Exhibitions’ (3 April 1819: 220). In this letter a (probably fictional) Frenchman urged for free access to art on certain days, reassuring nervous owners of paintings that the populace would be flattered and behave themselves accordingly. Jerdan, as a devoted admirer of art, was delighted with the new Gallery and expressed his appreciation in glowing terms. Sir John assumed Jerdan’s eloquence was equal to his knowledge of the subject, and on that basis, welcomed Jerdan into his circle of friends. This, recalled Jerdan, was “one of the most gratifying sources of pleasure and friendship which gave happiness to many days of my chequered life” (2.257). Many of these days were to be spent at Sir John’s estate, Tabley House in Knutsford, Cheshire. Jerdan happened to be visiting on the very day that Sir John received a letter from the Prince Regent raising him to the peerage, and he discussed the choice of title with his visitor. The peer chose de Tabley, but Jerdan suggested Warren, or Fitz-Warenne, on a heraldic basis, and was pleased when de Tabley’s heir added this name to his own on his father’s death. He noted that a wit suggested “de Tableaux” as more appropriate for a patron of the arts.

Jerdan relished his visits to Tabley House over a number of years. It was to him an earthly paradise, an escape for one so much a slave to the pen. He indulged in the country pursuits of hunting, shooting and fishing, and greatly admired his host’s skill with a shotgun. On one of Jerdan’s visits, another guest who was also a keen fisherman, was the great painter, J.M.W. Turner, to whom Lord de Tabley had been a generous patron, purchasing nine major works. In Autumn 1818 Turner visited Edinburgh in connection with Scott’s The Provincial Antiquities of Scotland. His visit to Tabley House may well have been a stop-over on his return to London.

The peer was an enthusiastic amateur painter himself and had left an unfinished landscape on his easel. Whilst the assembled company stood around discussing the painting, Jerdan stuck a bit of blue paper on to show where he thought it would be improved by a spot of brightness, and unasked, Turner took up a brush and marked a few improvements. Turner then returned to London, and at breakfast the next day de Tabley was furious to receive a bill from him for "Instructions in Painting". Jerdan tried to persuade him to ignore it, but de Tabley paid up, as Turner must have known he would. Jerdan called this a “deplorable instance of Turner’s eccentricity” but “as a sort of balance to the human infirmity of the Drawing Master account”, also related that Turner invited Thomas Hunt, an authority on Tudor architecture, to accompany him on a continental trip, paying all Hunt’s expenses. Tabley House still has Turner’s painting depicting the lake in the grounds where he and Jerdan fished, and the grooves cut into the floor by the artist’s easel may still be seen.

Returning from one of his visits to Tabley House, Jerdan went to call on Wordsworth at Rydal Mount. As he explained in Men I Have Known. the impression stayed in his mind for many years: “I was not unexpected, nor denied the favour of a first home-picture. On walking up the beautiful greensward, on a fine summer afternoon, towards the house, I at once saw the poet seated, almost in attitude, at an open window which descended to the ground, and with a handsome folio poised upon his crossed knee, which he seemed to be reading. Had those been the days of photographs, the position would have been invaluable” (476).

The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly designed by P. J. Robinson. 1811-12. Photograph 1895. The Hall, which was torn down in 1905, was at 170/171 Piccadilly.

Jerdan’s visual memory remained acute, even as an old man; he recalled in some detail many of the shows and art he had seen in his youth. Amongst his favourites were Mr Bullock’s displays at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, most particularly Napoleon’s carriage, just as he had abandoned it in his flight from Waterloo, complete with its coachman, a great coup for Bullock and one which attracted a total of 220,000 visitors during its seven months on display (Altick 240). Jerdan saved a letter from Bullock exulting over his acquisition, gloating that it had given him “the opportunity of accomplishing in a few months what he [Napoleon] could never succeed in doing; for in that short period I over-ran England, Ireland and Scotland, levying a willing contribution on upwards of 800,000 of his Majesty’s subjects; for old and young, rich and poor, clergy and laity, all ages, sexes, and conditions, flocked to pay their poll-tax and gratify their curiosity by an examination of the spoils of the dead lion.” Bullock's return on his £2,500 investment was £35,000. Jerdan plainly admired Bullock’s entrepreneurship in taking the moribund collection of natural history objects previously displayed at the Leverian Museum, and transforming them, with Bullock’s own collection, into a fascinating and educational exhibit, the first English museum to use the device of ‘habitat groups’ to display specimens as nearly as possible in their natural surroundings. Jerdan recalled this museum minutely in his mini-biography on Bullock more than forty years later. In Men I have Known he recalled how Bullock brought him a pony from Shetland, which Jerdan had to transport across London in a hackney coach, with its head sticking out of the window, transforming its owner into a showman.

It was Jerdan’s lot in his life as the Literary Gazette’s editor, to be bombarded with requests to print everything he was offered, and he was frequently expected to improve some amateur’s attempt at an Ode, or review, or an opinion on any matter. He became inured to the sycophantic language used to entreat his publishing of anything and everything sent to him, and made fun of the flowery terms used by these supplicants who “rejoiced” over a poem, sent with “highest pleasure”, “great delight”, “astonishment and rapture” and so on. His immediate attention to each offering was demanded, and his mealtimes and scant rest were often broken in upon by such importuners. He, like other editors then and since, could not always do as demanded, and Jerdan felt at the mercy of the wrath of disappointed writers, overlooked painters and poorly reviewed actors. Irritably, he noted that

most public characters have such capacious stomachs for applause, that there is no risk of surfeiting them with panegyric; but, on the contrary, much danger of being thought churls and niggardly starvlings for not giving enough, Reviews must be puffs – criticisms must observe no blemishes – biographies must make men angels! [2.301]

Jerdan was definitely no angel; he was sorely tried by poets who resented their immortal words being “polished”, especially poetesses who entreated him “with downcast eyes and heaving bosom” to print their verses. He was “martyred between the writer and the writing”. Actors who opined that their provincial tour was at least as important as the march of a general’s victorious army were another thorn in his side. He needed to be a diplomat and counsellor and, above all, focussed on his task of keeping the Literary Gazette both interesting and influential. One poet in particular went against the tide of those vying to be included in the Literary Gazette. In Men I Have Known Jerdan tells that he approached Wordsworth, on the eve of one of his overseas travels, to write a Diary for the journal; he offered the poet “a considerable sum”, but was refused on the grounds of “an idleness of disposition”.

There were compensations for all these petty annoyances. One was the satisfaction of Jerdan’s fervent interest in, and access to, all the variety of shows that London had to offer. These were not stage shows as we would recognise the term today, (although he was also a devotee of the theatre), but what he called ‘novelties’, recalling decades later that: “for some twenty-five years there was not a known show or curiosity , from the charge of a halfpenny to a guinea, that I did not see…giants, dwarfs, mermaids, Albinos, Hottentot Venuses, animals with more heads or legs than ‘they ought to’, and all other curiosities and monstrosities were ‘my affections’” (2.88). His passionate curiosity about all such popular shows became evident through reviews in the Literary Gazette, most if not all, apparently written by the editor himself.

Another compensation for Jerdan’s ‘martyrdom’ was that editorship allowed him access to important people whose acquaintance, and occasional friendship, he valued highly. He kept his friends for many years, often for a lifetime, and such attachments could have been not only for mutual benefit, but for mutual liking and esteem. Colonel Fitzclarence, Earl Munster, whose book Jerdan supervised through the press, changed from a dilettante to an ardent scholar and writer; he visited Jerdan at home, where his good humour was enjoyed by everyone. Jerdan also called on him at his home in Belgravia, to discuss literature and drawing, and where he was able to admire Lord Munster’s obvious affection for his family. Jerdan recounted that he was present when Fitzclarence, just after he had been made Earl, met the Earl of Mulgrave, recently raised to Marquis of Normanby. After much “Milording” between them, and with the lubrication of champagne, they agreed to drop their titles, calling each other simply George and Henry. Years later, Munster was accused in an anonymous letter Lord Mulgrave showed to Jerdan, of intriguing with the Duke of Wellington, and of being a “Gorse Hopper”. Jerdan and Mulgrave finally realised that Munster’s accuser was calling him a “Gossiper” – just the kind of word joke that Jerdan relished.

Jerdan loved parties, and recalled one particular gathering where the company played “Games and Forfeits”. He was made to kneel and bury his head in the lap of Lady Caroline Lamb (infamous as having been Byron’s mistress), there to answer any questions the other guests proposed. He was asked “What would you do if an injured ghost approached to assault you, for wrongs done in the flesh?” Before he could answer, he was indeed assaulted, with a knock to his head. On taking off his blindfold, he looked up into the face of William Lamb, Lady Caroline’s husband, come to collect his wife from the party. Jerdan felt uncomfortable at being the butt of a silly joke, but decided not to call Lamb out for a duel. This was fortunate, for Lamb later became Lord Melbourne, beloved adviser to the young Queen Victoria and future Premier and powerful ruler of the empire. Melbourne and Jerdan became more closely acquainted over the years, but even the ambitious Jerdan did not claim that they became real friends. He tried unsuccessfully to interest the Premier in doing something for literary men, and occasionally published Melbourne’s own poems in the Literary Gazette. A few years later Jerdan used his access to Melbourne to plead for aid for the widows of the brothers Lander, intrepid explorers of Africa who, in 1830, discovered the course of the River Niger, and one of whom died in 1834; Jerdan helped to procure pensions for them, one of which was still being paid, through him, until at least 1852. On Melbourne’s death, in 1848, Jerdan was consulted about his life by Melbourne’s friend, Sir Henry Bulwer, an acknowledgement that he was considered to have known the Premier well enough to have something to say about this powerful and esteemed statesman.

Now that he was established at the Literary Gazette, Jerdan often found himself in exalted company, not always as a result of any flattery on his part. Horace Twiss, a Tory MP famous for his unconventionally flippant speeches, produced a novel in 1819 called Carib Chief. The Literary Gazette was mildly critical of this work. A few years later Twiss attained political eminence, which provoked jealousy in some literary men, who ridiculed his wit and lampooned him for his foibles. Despite the paper’s indifferent review, Twiss invited Jerdan to dine in his “dark little dining room in Serle Street,” Lincolns Inn, with other guests including Lord Eldon, Lord Castlereagh and other Cabinet Ministers. Jerdan and Twiss remained close friends for thirty years, until Twiss’s death in 1849, unaffected by the Literary Gazette’s misgivings about his literary production.

The Literary Gazette gave a warmer reception to Washington Irving’s Sketch Book. William Pyne sent a copy to Jerdan at Hastings, where he was enjoying a brief respite, accompanying the book with an amusing letter which Jerdan called facetious, correcting Jerdan’s assumption that the man who had purchased it in New York, “wet from the press” was the author, a pardonable mistake as Irving used the pseudonym Geoffrey Crayon. Jerdan corrected his error in the following issue of the Literary Gazette. The Sketch Book was a huge success in Britain, and Jerdan received a gratifying note of thanks from Irving: “The author of the Sketch Book cannot but feel highly flattered that his Essays should be deemed worthy of insertion in so elegant and polite a miscellany as the Literary Gazette…he begs leave to add his conviction that he could not have a better introduction to fashionable notice than the favourable countenance of the Literary Gazette.” Although oblivious to Irving’s implicit complaint that the Literary Gazette had given too long an extract from his book, Jerdan noted that this was one of the “most grateful incidents of my literary life”; he modestly did not take full credit for the book’s success, acknowledging that: “No doubt, without my aid, the beautiful American canoe would soon have been safely launched on the British waters; but as it was, I had the pleasure and honour to launch it at once, fill the sails, and send it on its prosperous voyage” (2.290). Jerdan entertained Irving in his home, together with Edward and Henry Bulwer, Thomas Moore and others of great literary renown; Irving’s retiring character and the editor’s hectic life precluded their developing a close friendship, but it was a source of pride to Jerdan that they held each other in high esteem. When a parody of Scott’s ‘Lay of the Last Minstrel’ called ‘The Lay of the Scottish Fiddle’ was incorrectly advertised in the newspapers as being the work of Washington Irving, Jerdan was asked by John Miller to set the matter right by an announcement in the Literary Gazette (11 November 1820, National Library of Scotland, 948/26).

Thomas Moore: The poet of all circles, the delight of his own.

From The Illustrated London News (4 February 1843): 73..

Irving’s discreet hint that the Literary Gazette’s extracts from his book were too long, and thus could inhibit sales of his book, became a familiar complaint from authors. Jerdan took no notice, and several years later was still doing the same thing. He enraged Thomas Moore in 1827 by printing the climax of his book The Epicurean, whilst praising it generously, thus obviating the need for readers to buy it.

The space Jerdan allocated to book reviews has been calculated from an average of about 1500 words in 1818, representing about 135 works, to 3800 in 1826, representing 425 reviews and notices (Pyle 68). Reviews remained within ten percent of this for the rest of Jerdan’s tenure. These averages encompass a review of 12,000 words in 1826, (which was extended in following issues), and any review of Scott which was double the average. Within these figures the quantity of extracted text from the work reviewed rose from about 43% in 1818 to 65% in 1826 and over 80% in 1847. This steep rise in 1847 may have reflected Jerdan’s disenchantment with his paper which was by then in rapid decline. The practice of including lengthy extracts was not due to laziness; it was in accord with Jerdan’s plan at the outset of his editorship, when he announced his intention to quote at length, a practice which had been common in eighteenth-century magazines and newspapers. On one hand this filled many columns without the need to pay a reviewer to write long articles, and saved time in getting reviews out before or at publication date of the work discussed. On the other hand, the Literary Gazette, aimed as it was at the middle classes and young readers of Scott and the miscellanies, could be read to the family in the evenings, keeping them sufficiently abreast of the content of new books without the necessity of purchasing them. Publishers were in a cleft stick, needing the Literary Gazette to review their books, but unhappy if the extracts satisfied readers to the extent they did not purchase the book.

On Saturday 26 June 1819 Bensley’s printing house caught fire. That week’s Literary Gazette had fortunately already been distributed to the publisher and newsmen, but Jerdan lost most of his back stock, records and manuscripts. It was necessary to reprint the lost stock at considerable expense. The Gazette’s first printer, Messrs Valpy, helped out, a kindly gesture as they had been usurped by Pinnock and Maunder’s connection with Bensley. A new printer was shortly engaged, Mr Pople of Chancery Lane, who thereafter printed the Literary Gazette for some years.

Pinnock and Maunder’s business had now declined to such an extent that they could no longer act as publishers of the Literary Gazette. In November their names vanished from the journal and Jerdan, with Colburn, made temporary arrangements for new offices at 268 Strand, and a new publisher. In January 1820 Jerdan appointed William Armiger Scripps of 362 Strand, who had been the publisher of the Sun in Jerdan’s days there as a journalist; he remained the publisher for over a quarter of a century.

All these changes and difficulties created great strain on Jerdan. Colburn had not made a return on his investment in the first three years of the Literary Gazette, and Jerdan said that despite the hard work he had put into the journal, his remuneration was that of a porter and he needed to improve his income. At his wit’s end, he wrote to Colburn resigning his editorship. He was in a strong position, having received an offer from the British and Foreign Library in June, to edit a new Review. There was a supporting fund of ten thousand pounds and the certainty of a good salary for the Editor. Surprisingly, for one so impecunious, Jerdan turned this generous offer down, being “more inclined to stick to my first love, especially as I was courting a bit of change by way of variety” (3.324). This decision was typical of Jerdan, to put an emotional reason above the practical necessity of a certain income.