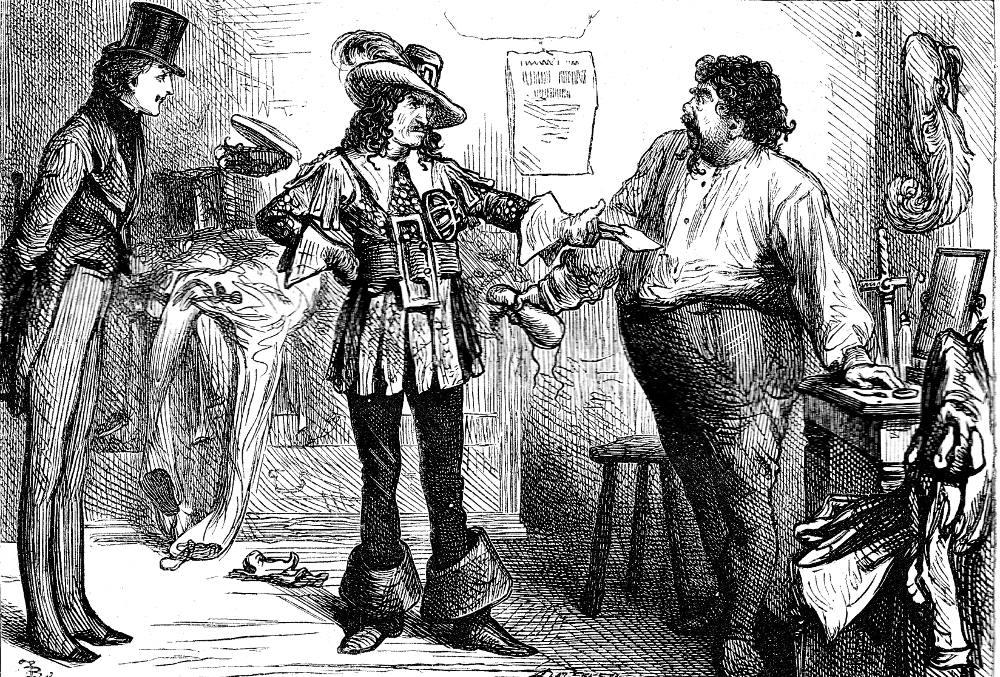

Mr. and Mrs. Crummles and The Phenomenon, depicted by Sol Eytinge. Jr. in the 1867 Diamond Edition of Nicholas Nickleby.

Vincent Crummles's seedy touring theatrical company is the subject of considerable satire in Dickens's picaresque novel Nicholas Nickleby. Centred on the impressario himself, his business-minded wife, and their headlining child-actress, the company shelters Nicholas under the pseudonym "Mr. Johnson," taking him in as resident playwright, adapter, and translator of French farces for the provincial English stage. The chapters involving the company's theatricals (23-25, 29-30, and 48) would have been based in part on Dickens's own attempts to become a thespian, and in part on his close personal relationships with such figures of nineteenth-century theatre as the great actor-manager of Drury Lane, William C. Macready (1793-1873). Dickens, for example, praised Macready's restoration of the original text of Shakespeare's King Lear in a theatrical review in The Examiner for 4 February 1838.

Critics have, however, assumed a much more direct source of inspiration here. Paul Schlicke in “Crummles Once More” (1990) asserts that “one of the most widely accepted identifications of a real person with a fictional personage is the claim that the real theatrical manager Thomas Donald Davenport (1792-1851) and his actress daughter Jean Margaret (182?-1903) who became one of the most celebrated juvenile actresses of the early Victorian period, were the prototypes for Vincent Crummles and his Infant Phenomenon. Davenport himself is supposed to have spoken out repeatedly about the connection” (2). The connection matters because, as Michael Slater remarks in his introduction to the Penguin Edition of the novel, these theatrical chapters of the novel are “its living heart.” In a sense, then, the actor-manager Vincent Crummles represents or epitomizes the sheer theatricality of Dickens’s third novel, and constitutes Dickens's entertaining critique of the early Victorian theatre.

Dickens and the Davenports

Left: playbill, p. 135 for the Theatre, Rye, 12 June 1837, announcing Jean as Sir Peter Teazle in Sheridan’s The School for Scandal and a multi-part character tour-de-force in a lesser piece, The Manager’s Daughter. (Courtesy of the Harvard College Library).

R. S. Maclean posits that Dickens first became aware of the theatrical family at the (illegal or unlicensed) Westminster Subscription Theatre on Tothill Street in the spring of 1832. Certainly, when he was a reporter for the True Sun, Dickens would have passed and re-passed this playhouse going to and from the House of Commons nearby. There are even unsubstantiated stories that in his off hours Dickens worked with Davenport for a time, but proved unsuccessful because “he could not learn five or six parts a week” (Maclean 142). Be that as it may, Dickens is likely to have seen Davenport's production of an adaptation of Sir Walter Scott’s historical novel Rob Roy at the Westminster Theatre in June 1832, in which Mrs. Davenport, then aged about 50, played Helen McGregor, and her husband the title character. When the Davenports' daughter Jean was seven or nine (her age was open to debate), she debuted at the Richmond Theatre on the Surrey side of the Thames in 1836. Dickens is likely to have seen this performance too. The sequence involving the Crummles family can also be connected to Davenports' leasing the Portsmouth Theatre at this time, in order to showcase the girl's precocious talent. This was the very year before Dickens started writing Nicholas Nickleby. The most popular drama of these early years, says Paul Schlicke, was Douglas Jerrold's Black-Eyed Susan (first published and performed in 1829). This was inevitably staged in Portsmouth (Dickens and Popular Entertainment, 57), and Dickens, as an avid theatre-goer, would at the very least have been aware of this on his visit to the town when writing the novel. Jean's performance at the Portsmouth Theatre in May 1837 is recorded in playbills from the period.

How would the Davenports have struck Dickens? Maclean tells us that the Anglo-American actor William Pleater Davidge (1814-88), who toured Kent with Davenport’s company in 1837, provides in both newspaper reports such as The New York Mirror (11 August 1888) and his theatrical memoirs Footnight Flashes, accounts of the "strolling" company that looks very much like Crummles’s. Davidge played opposite Jean throughout the south of England in little villages such as Folkstone, Rye, and Ashford, when the “Infant” was in fact “a buxom lass of twelve or fourteen with stout legs and a florid complexion” (MacLean 133-134). As in various representations of her alter-ego in the novel, Jean “was always dressed in short dresses and pantalettes and neat slippers” (134) with her hair inbraids and wearing a large, wide-brimmed hat. She looked, recalls Davidge, only about nine years old. MacLean characterizes Davenport himself “as something of a shrewd ham” (138), ever ready to promote his daughter’s talents and the company’s arrival in the next town on tour. He was, reflects MacLean, the ideal model for Dickens's provincial manager: “Davenport had a sense of showmanship and a grandiloquence” (138) with a bent for issuing self-promoting playbills. “Another Crummles-like trait of Davenport’s publicity was his constant admonition to the public of the brevity of the theatrical appearance of his compmany, on the one hand; while, on the other, he made seemingly endless extensions of his planned engagement” (141). Significant to Dickens's references to Davenport through Crummles, and the various illustrators’ realisations of Crummles, was the fact that he was “a man of about twelve stone,” according to a review by Gilbert Abbott a Beckett. As for his daughter, other early reviewers of the Davenports’ performances during their later overseas tours, in Washington, D. C., and the Caribbean, noted not only her appearance but also the fact that she was not a particularly talented actress because her father had neglected her education and had exploited her throughout her childhood. Schlicke concludes that “the level of ability, the pomposity, and the vaunting of family pretensions could well have fired Dickens’s imagination” ("Crummles Once More," 8) in creating the theatrical Crummleses.

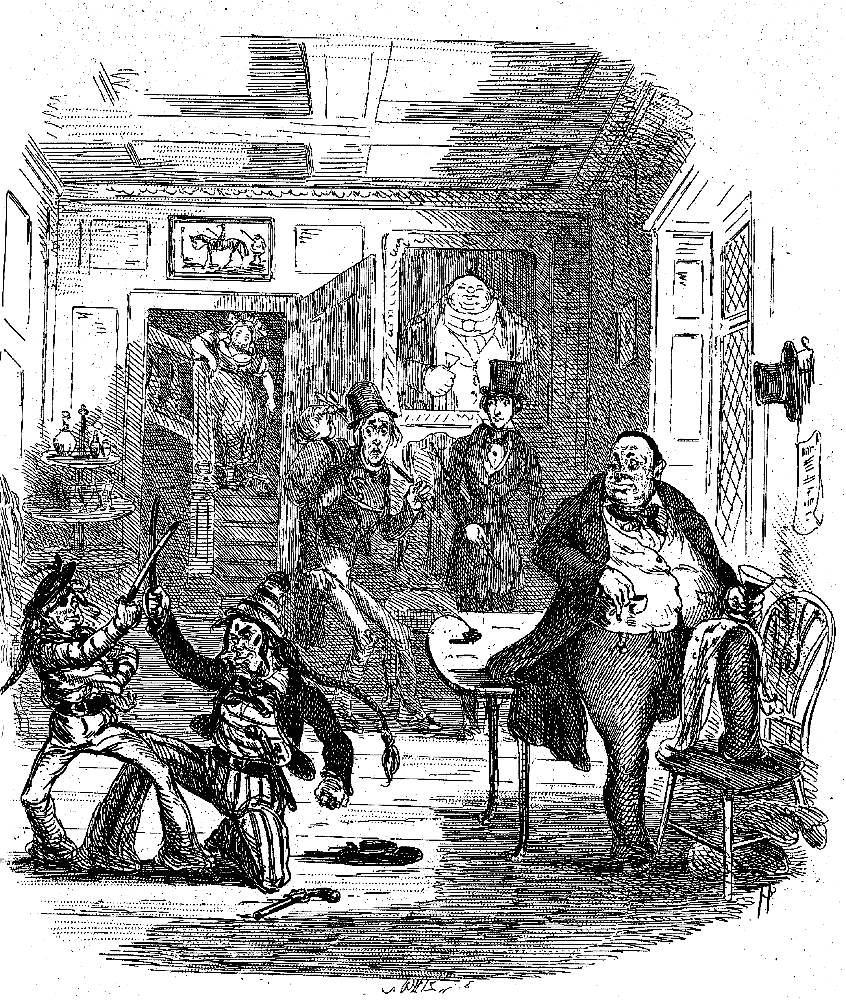

In the October 1838 serial instalment of the novel, Phiz introduces Vincent Crummles stage-managing the rehearsal of a transpontine duel: The Country Manager Rehearses a Combat (Chapter 22).

In the novel, Nicholas and Smike stumble upon Crummles quite by accident at a road-side inn, where he is rehearsing a pair of mismatched juvenile actors in a duelling scene from a transpontine or seafaring drama of the type popular in the early Victorian period. They are dressed in nautical costumes and the violence of their cutlass duel startles Smike, as depicted in Phiz's steel engraving, whereas in this illustration, Nicholas in respectable beaver and frockcoat (rear, centre right) is only moderately interested, for he realises that the fight is only a mock one. Phiz depicts the setting of the encounter, the main hall of an old rural coaching inn, with considerable detail, including a writing table by the lead-paned window which seems to invite Nicholas to be seated and assume his role as the touring company's resident playwright. It is the beginning of Dickens's amusing recreation of the company's activities.

The Davenports in later years

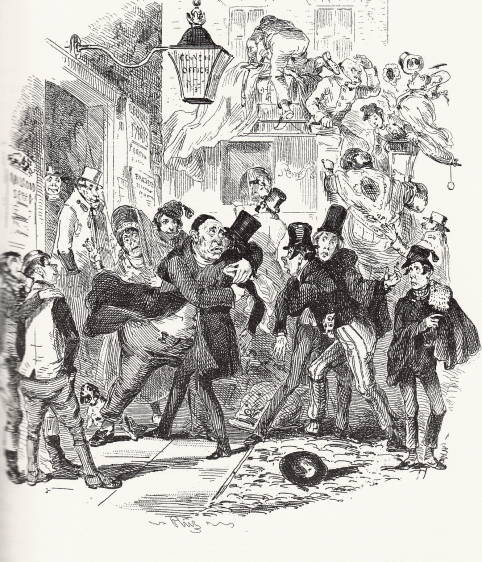

In the January 1839 serial instalment of the novel, Phiz shows Crummles making his over-the-top farewells prior to his American tour: Theatrical Emotion of Mr. Vincent Crummles (Chapter 30).

The "strolling" Crummleses take ship for America in Chapter 30 of Nicholas Nickleby, just as Nicholas and Smike had intended to do earlier in the novel. "Ninetta," as the precocious child-actor is called now, seems to be at least fifteen when Nicholas and Smike encounter her on the way to Portsmouth. The Davenports themselves "strolled" far beyond England. Schlicke records their travels after crossing the Atlantic, performing in New York, Philadelphia, Buffalo, and Boston, recrossing the Atlantic to do Florence and Paris before returning to England in 1843. Among other stops in their extensive travels were those in Canada, including Montreal, where they performed at the Queen's Theatre.

Since the work featuring Crummles and daughter was serialised in the United States in the autumn of 1838, American audiences would probably have recognized Jean as the original of Dickens's "The Infant Phenomenon" when she first appeared there, but by this stage she was obviously too old to be an “Infant Phenomenon." She became a tragedienne, going on to act, on the company's return home, at various London theatres as well as on the Kent and Norwich circuits, Holland, and Germany. She retired from acting temporarily when she married General Lander in 1860, but returned to the American stage, enjoying considerable celebrity as "Mrs. Lander," and touring throughout the United States. This latter part of the acting history, of course, has little relevance for the characters of Crummles and daughter as Dickens presents them in Nicholas Nickleby.

The Davenports and Dickens's later work

However, Nicholas Nickleby was not the only one of Dickens's works with links to the the Davenports. In the 1846 Colchester production of Dickens's third Christmas novella, The Cricket on the Hearth, stage-managed by her father, seventeen-year-old (or so) Jean played Dot Peerybingle, the carrier's young wife. On the London stage, too, Jean starred as Dot in an adaptation of The Cricket on the Hearth (originally published in December 1845, but subsequently adapted for the stage as a seasonal favourite). Both father and daughter were involved in the December 1846 production of The Battle of Life (Dickens's fourth Christmas Book) at the Theatre Royal, Norwich, in January 1847, an adaptation which they may have hurriedly co-authored (Bolton 299). Jean took to the boards as Dot Peerybingle once again at the Theatre Royal, Lynn, in February 1847, and again in her early 30s at the Boston Museum in Dion Boucicault's Dot!, his vastly popular and spectacular adaptation of The Cricket on the Hearth, in February 1860.

Postscript: The Infant Phenomenon

The effusive title which Dickens bestows upon Ninetta he may well have derived from playbills of the period. As Schlicke notes in his Oxford Companion article, the term "infant phenomenon" was commonly applied during the period to child actors and actresses generally, but was "facetiously adopted by Dickens to describe his first-born son ... and most memorably applied to Ninetta Crummles, the daughter of Dickens's strolling actor-manager" (296).

Images of Vincent Crummles and The Infant Phenomenon (1861 to 1910)

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's 1861 lithographic frontispiece The Rehearsal (1861). Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 lithograph representing the same scene, Nicholas and Smike behind the Scenes, in the Charles Dickens Library Edition.

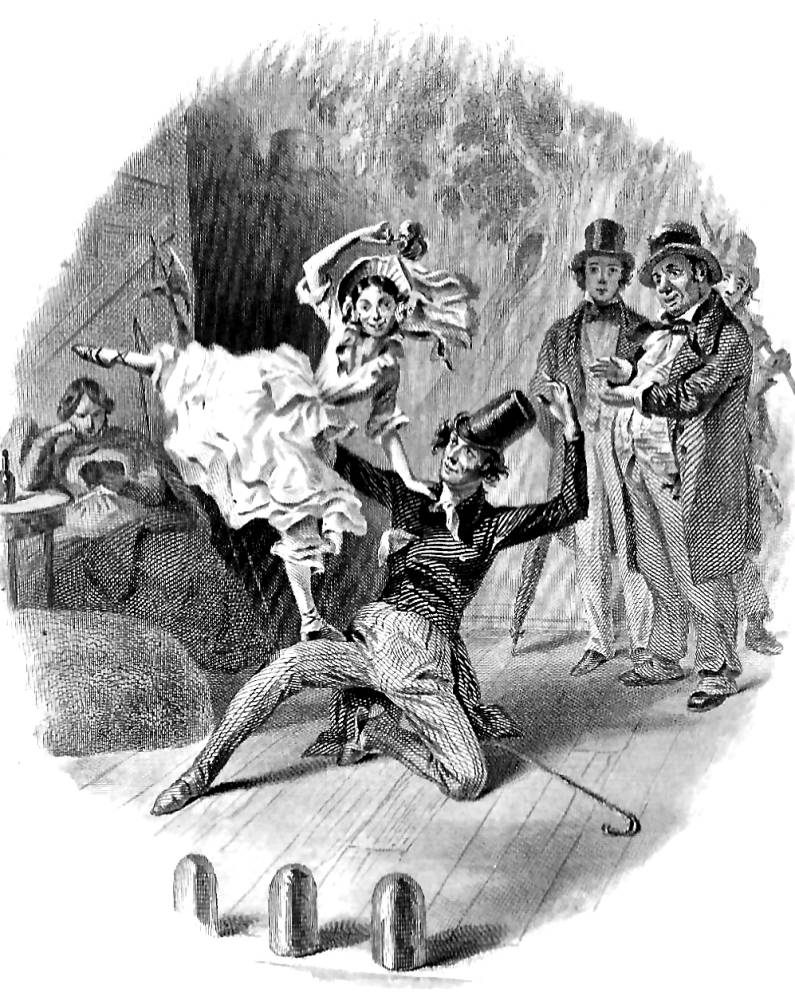

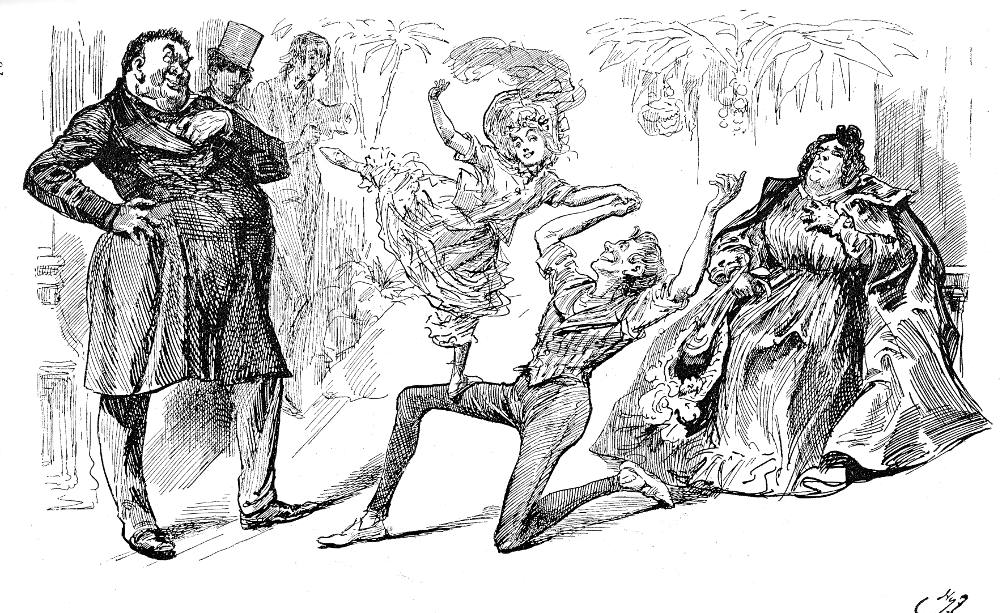

Left: Fred Barnard 1875 Household Editioncomposite woodblock engraving of the melodramatic dance number: The Indian Savage and the Maiden. Right: C. S. Reinhart's version of the same "Indian Savage and Maiden" dance number: And finally the Savage dropped down on one knee, and the maiden stood on one leg on his other knee (1875).

The British Household Edition's Handling of the Last of Vincent Crummles (1875)

Above: Fred Barnard's Household Edition handling of the same scene: Was presently conducted by a robber, with a very large belt and buckle round his waist, and very large leather gauntlets on his hands, into the presence of the former manager (1875).

Bibliography

Bolton, H. Philip. Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1839.

_______. Nicolas Nickleby. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). The Gadshill Edition, ed. Andrew Lang. The Works of Charles Dickens in Thirty-four Volumes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1897. Vols. IV and V.

_______. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. Boston: James R. Osgood & Co., Late Ticknor and Fields, and Fields, Osgood, & Co., 1875 [re-print of 1867 Diamond Edition, Vol. IV].

_______. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-two illustrations by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1875. I.

_______. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-nine illustrations by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. IV.

__________. Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. IV.

MacLean, R. S. “How the ‘Infant Phenomenon’ Began the World: the Managing of Jean Margaret Davenport (182?-1903).” Dickensian 88 (1992): 133-153.

Schlicke, Paul. "Crummles Once More." Dickensian 86 (1990): 2-16.

_____. Dickens and Popular Entertainment. London: Unwin Hayman, 1985.

_____. "Infant Phenomena." The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. P. 296.

Schweitzer, Maria. "Jean Margaret Davenport." Ambassadors of Empire: Child Performers and Anglo-American Audiences,

1800s-1880s. Accessed 19 April 2021. Posted 7 January 2015.

Vann, J. Don. "The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, twenty parts in nineteen monthly installments, April 1838-October 1839." New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. 63.

Created 5 October 2021