Mr. and Mrs. Crummles and The Phenomenon

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby (Diamond Edition), facing IV, 163.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration—> Sol Eytinge, Jr. —> Nicholas Nickleby —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Mr. and Mrs. Crummles and The Phenomenon

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby (Diamond Edition), facing IV, 163.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"Is this a theatre?" whispered Smike, in amazement; "I thought it was a blaze of light and finery."

"Why, so it is," replied Nicholas, hardly less surprised; "but not by day, Smike — not by day."

The manager’s voice recalled him from a more careful inspection of the building, to the opposite side of the proscenium, where, at a small mahogany table with rickety legs and of an oblong shape, sat a stout, portly female, apparently between forty and fifty, in a tarnished silk cloak, with her bonnet dangling by the strings in her hand, and her hair (of which she had a great quantity) braided in a large festoon over each temple.

"Mr. Johnson," said the manager (for Nicholas had given the name which Newman Noggs had bestowed upon him in his conversation with Mrs. Kenwigs), "let me introduce Mrs. Vincent Crummles."

"I am glad to see you, sir," said Mrs. Vincent Crummles, in a sepulchral voice. "I am very glad to see you, and still more happy to hail you as a promising member of our corps."

The lady shook Nicholas by the hand as she addressed him in these terms; he saw it was a large one, but had not expected quite such an iron grip as that with which she honoured him.

"And this," said the lady, crossing to Smike, as tragic actresses cross when they obey a stage direction, "and this is the other. You too, are welcome, sir."

"He’ll do, I think, my dear?" said the manager, taking a pinch of snuff.

"He is admirable," replied the lady. "An acquisition indeed."

As Mrs. Vincent Crummles recrossed back to the table, there bounded on to the stage from some mysterious inlet, a little girl in a dirty white frock with tucks up to the knees, short trousers, sandaled shoes, white spencer, pink gauze bonnet, green veil and curl papers; who turned a pirouette, cut twice in the air, turned another pirouette, then, looking off at the opposite wing, shrieked, bounded forward to within six inches of the footlights, and fell into a beautiful attitude of terror, as a shabby gentleman in an old pair of buff slippers came in at one powerful slide, and chattering his teeth, fiercely brandished a walking-stick. . . . .

"Your daughter?" inquired Nicholas.

"My daughter — my daughter," replied Mr. Vincent Crummles; "the idol of every place we go into, sir. We have had complimentary letters about this girl, sir, from the nobility and gentry of almost every town in England."

"I am not surprised at that," said Nicholas; "she must be quite a natural genius."

"Quite a —!" Mr. Crummles stopped: language was not powerful enough to describe the infant phenomenon. "I’ll tell you what, sir," he said; "the talent of this child is not to be imagined. She must be seen, sir — seen — to be ever so faintly appreciated. There; go to your mother, my dear."

"May I ask how old she is?" inquired Nicholas.

"You may, sir," replied Mr. Crummles, looking steadily in his questioner’s face, as some men do when they have doubts about being implicitly believed in what they are going to say. "She is ten years of age, sir."

"Not more!"

"Not a day."

"Dear me!" said Nicholas, "it’s extraordinary."

It was; for the infant phenomenon, though of short stature, had a comparatively aged countenance, and had moreover been precisely the same age— not perhaps to the full extent of the memory of the oldest inhabitant, but certainly for five good years. But she had been kept up late every night, and put upon an unlimited allowance of gin-and-water from infancy, to prevent her growing tall, and perhaps this system of training had produced in the infant phenomenon these additional phenomena. [Chapter XXIII, "Treats of the Company of Mr. Vincent Crummles, and of his Affairs, Domestic and Theatrical," 163-164]

The seedy theatrical company which shelters Nicholas (under the pseudonym "Mr. Johnson") as resident playwright, adapter, and translator of French farces is the subject of considerable satire in Nicholas Nickleby. Dickens may have based this part of the novel in part on his own aspirations to become a thespian, and in part on his close personal relationships with such figures of nineteenth-century theatre as the great actor-manager of Drury Lane, William C. Macready (1793-1873), whose restoration of the original text of Shakespeare's King Lear Dickens praised in a theatrical review in The Examiner for 4 February 1838.

Dickens describes the core of the company, the Crummles family, in some detail in Chapter 22, "Nicholas, accompanied by Smike, sallies forth to seek his Fortune. He encounters Mr. Vincent Crummles; and who he was, is herein made manifest," and in Chapter 23 (in which the present Eytinge illustration is positioned). According to The Dickens Index, Dickens based Vincent Crummles and his daughter Ninetta, "The Infant Phenomenon," on actor-manager Thomas D. Davenport (1792-1851) and his versatile actress daughter Jean Margaret (1829-1903), one of the most celebrated juvenile actresses of the period. Jean Margaret Davenport (May 3, 1829, Wolverhampton, England – August 3, 1903, Washington, D. C.), later Mrs. Frederick William Lander, became headliner in both England, Canada, and the United States. Jean made a juvenile a debut at the Drury Lane Theatre, but is best remembered for her provincial and American tours.

Undoubtedly the sequence involving the Crummles family in Dickens's 1838-39 novel is connected with Thomas Davenport's leasing the Portsmouth Theatre the year before to showcase the precocious talents of eight-year-old Jean, whom Dickens had seen make her stage debut at The Richmond Theatre, Surrey, in 1836. After their escape from the Yorkshire school, Nicholas and Smike stumble upon the theatrical impressario Vincent Crummles quite by accident at a road-side inn, where the manager is rehearsing a pair of juvenile actors in a duelling scene from a transpontine drama of the type popular in the period.

The "strolling" Crummleses (Davenports) took ship for America, just as Nicholas and Smike had intended to do in Dickens's novel, and Jean was presented to audiences as "an infant phenomenon." Back on the London stage in the 1840s, Jean Davenport starred as the young wife, Dot, in Albert Smith's adaptation of Dickens's third Christmas Book, The Cricket on the Hearth (opening 21 December 1846) in Colchester and again at The Royal Theatre, Lynn (opening 27 February 1847) under her father's management and direction.

American audiences would have recognized Jean Davenport (born in 1829) as the original of Dickens's supposedly ten-year-old "Infant Phenomenon," although Dickens implies that she is at least fifteen when Nicholas and Smike encounter her. Jean and her parents "visited North America in the late fall of 1838 and remained on the continent for close to a year, with stops in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, New Orleans, Kingston (Upper Canada), and Montreal. The tour was successful and so in the summer of 1840, the Davenports undertook a second lengthy tour of the colonies, this time with additional stops in the Caribbean and the Maritime colonies. The Davenports documented the company’s travels in scrapbooks of varying sizes and shapes, many of which exist today in the Manuscripts Collection at the Library of Congress" (Sweitzer).

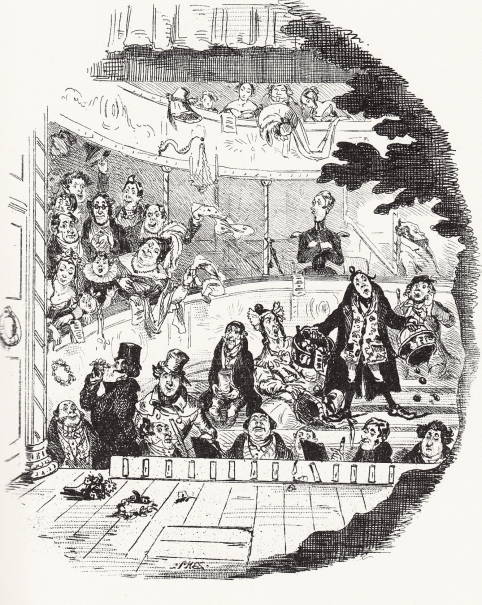

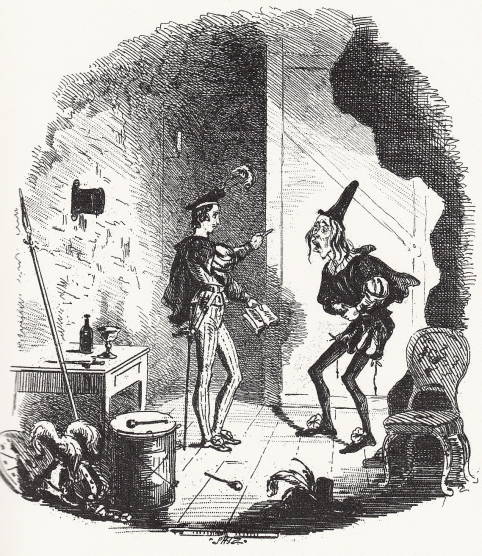

Left: The Country Manager Rehearses a Combat (October 1838), in which Phiz introduces Nicholas, Smike, and the reader to the Victorian theatre behind the scenes. Centre: The Great Bespeak for Miss Snevellici, in which the reader must adopt the actors' perspective of the ragtag provincial audience. Right: Nicholas Instructs Smike in the Art of Acting, in which Nicholas's caricatured companion struggles to learn his minor part, despite his friend's best efforts (November 1838).

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's 1861 lithographic frontispiece The Rehearsal (1861). Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 lithograph representing the same scene, Nicholas and Smike behind the Scenes, in the Charles Dickens Library Edition.

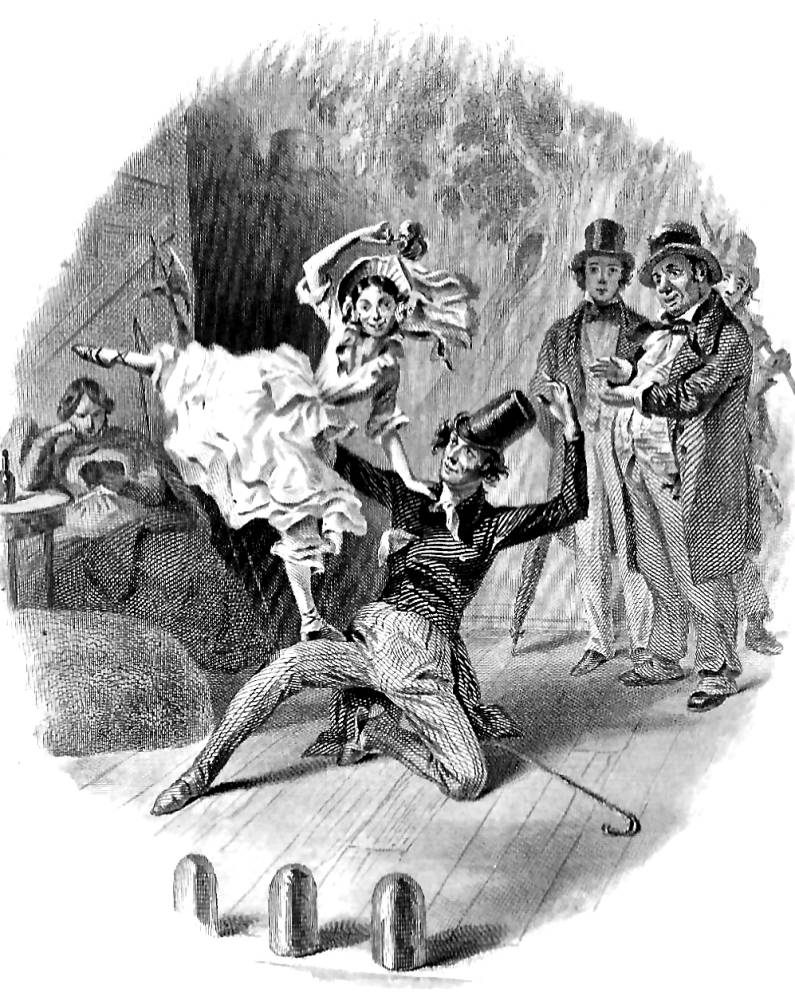

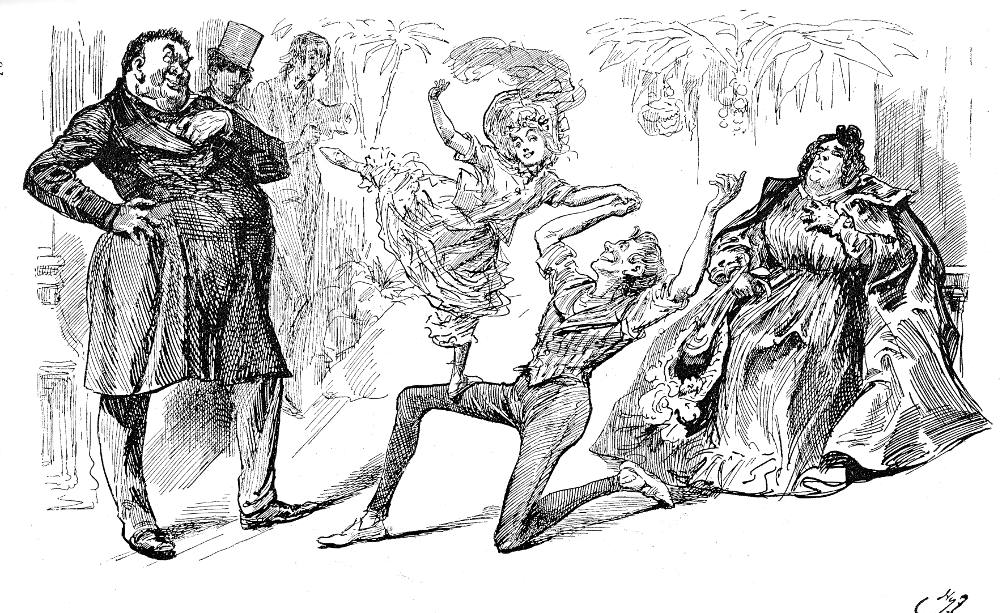

Left: Fred Barnard 1875 Household Editioncomposite woodblock engraving of the melodramatic dance number: The Indian Savage and the Maiden. Right: C. S. Reinhart's version of the same "Indian Savage and Maiden" dance number: And finally the Savage dropped down on one knee, and the maiden stood on one leg on his other knee (1875).

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1839.

_______. Nicholas Nickleby.Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. IV.

_______. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Ed. Andrew Lang. Illustrated by 'Phiz' (Hablot Knight Browne). The Gadshill Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1897. 2 vols.

_______. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 9.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 12: Nicholas Nickleby." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17, 147-170.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens andHis Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer,Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering,1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester Valerie Browne. Chapter 8., "Travels with Boz." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. 58-69.

Loomis, Rick. First American Editions of Charles Dickens: The Callinescu Collection, Part 1. Yarmouth, ME: Sumner & Stillman, 2010.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader'sCompanion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 14-50.

Schweitzer, Maria. "Jean Margaret Davenport." Ambassadors of Empire: Child Performers and Anglo-American Audiences,

1800s-1880s. Accessed 19 April 2021. Posted 7 January 2015.

Vann, J. Don. "Nicholas Nickleby." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 63.

Winter, William. "Charles Dickens" and "Sol Eytinge." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 181-202, 317-319.

Last modified 19 April 2021