Wehnert’s parentage has persuaded some critics to describe him as a ‘German artist’. It is more accurate to say that he was of German extraction, a London-born Englishman whose parents happened to have originated elsewhere. But the bilingual Wehnert must have felt a great affinity with the culture of the ‘old country’, was educated in Germany, and was certainly a ‘Germanic artist’.

The ‘German style’, Albert’s natural favourite, was popular in England in the 1840s and 50s, and Wehnert modelled his illustrations on the art of Hasenclever, Rethel and Retzsch. In this respect he was similar to many others; encouraged by publishers such as Burns, the German idiom was deployed by artists as diverse as Maclise, Selous, Pickersgill, and Tenniel, and Wehnert is best understood as another practitioner in a crowded field. Indeed, he is closely linked with these contemporaries. Like them, he explores the Germanic interest in psychological drama, as well as incorporating such well-known motifs as strap-work and rustic borders. He notably deploys Retzsch’s outline style while also using the excessive ornamentation of Rethel. Some of his books, such as More Fun for Our Little Friends (1864) are austere and pared down in the manner of Retzsch, while others are teeming with detail, an approach favoured in Robinson Cruscoe (1862), and in his illustrations for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1857) and The Eve of St Agnes (1859).

However, Wehnert’s reading of this idiom sometimes differs from that of his peers, and is far from ‘beautiful’ in the conventional sense of the term. He often plays with the original viewers’ understandings of the style, offering designs that seem to question conservative notions of taste by presenting the British audience with a stark and uncompromising version of the Germanic prototype. He is especially adept in the manipulation of the German grotesque. In Ruskin’s terms, as outlined in ‘Grotesque Renaissance’ (1853), his images are classic examples of this complicated idiom, ‘composed of two elements, one ludicrous, the other fearful’ (p.151).

Wehnert's Christmas Sports

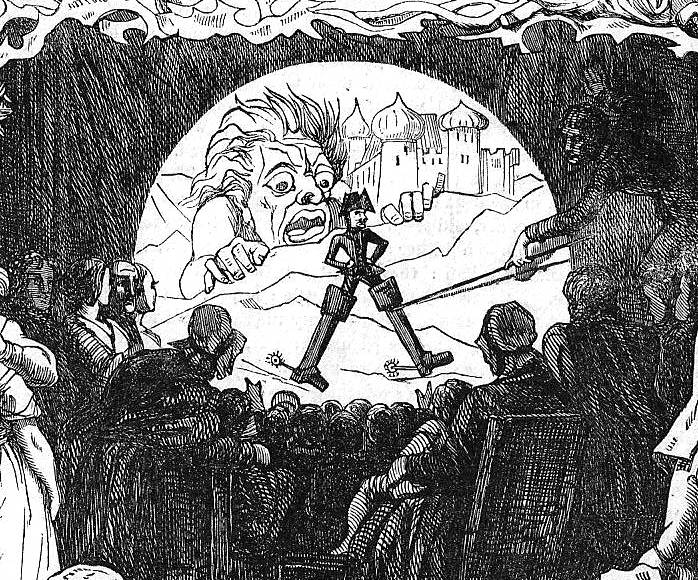

This mixing of levels and types of experience characterises his humorous illustrations of the late forties. In ‘Christmas Sports’ for The Illustrated London News (1848, Christmas Supplement, p.406), his design ranges across the surreal menace of the giant projected by a magic lantern; the light romance of courtship; dynamic figures milling around and tormenting a crocodile; a proliferation of sharp-looking knives; a dour oxen soon to go on the spit; and (unexpectedly slotted into the bottom left hand corner), a glum bailiff or ‘bill-man’ who will have to be paid following the festive indulgence.

“The surreal menace of the giant projected by a magic lantern; the light romance of courtship; dynamic figures milling around and tormenting a crocodile; a proliferation of sharp-looking knives; a glum bailiff.” [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

The commission calls for straightforward fun, but the humour is both vital and melancholy. It is interesting to compare it with Doyle’s treatment of the Germanic foliate swirl on the front cover of Punch. Far lighter in tone, it possesses precisely the uncomplicated joyousness Wehnert’s illustration does not.

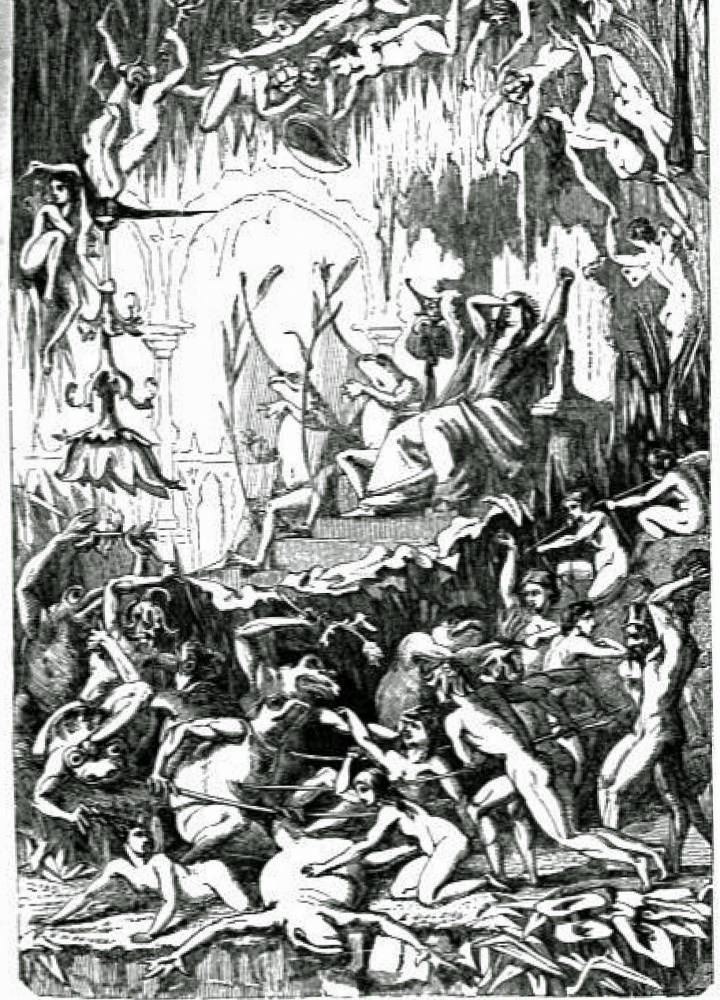

Wehnert’s The Discomfiture of the Kelpies

Wehnert’s fascination with the grotesque can also be seen, and is taken to an absolute extreme, in his design for Hall’s Midsummer Eve, which was published shortly after’s the artist’s death in 1870. This illustration, a showing of ‘The Discomfiture of the Kelpies’ (frontispiece, facing. p. 50), is a representation of the lines ‘The turmoil was terrible; a fierce war between the imps, her pages, and her frogs’ [had broken out] (p. 72). In Wehnert’s reading, however, the emphasis is on the horrific, taking the text to a new level of disconcerting intensity. The violence is bluntly interpreted, with grotesque figures of frogs and miniature nudes – shown here with unusual sensuality – mixed together in a graphic melée of violence and suffering. The effect uncannily recalls the ‘madhouse’ art of Richard Dadd and also figures the representation of the tormented population of Hell in Bosch’s celebrated altarpiece of The Garden of Earthly Delights (1510; Prado, Madrid). Placed next to the fey representations of the little people found elsewhere in the book, notably those in Maclise’s ‘Vision of the Wood-cutter’ (facing p. 130), it seems a calculated attempt to present the viewer with an unmodified ugliness.

This approach features throughout Wehnert’s work and in each case he forces the viewer to contemplate incongruity and especially the darker elements within the fantastical and comedic. In this sense his art is linked to Cruikshank’s, but Wehnert takes the process of unsettling the audience much further than his older colleague. Indeed, it is my view that Wehnert systematically sets out to present a distinct world-view, one in which suffering pervades the ordinary. He uses the grotesque, in other words, for personal, expressive purposes. Though employed as a journeyman illustrator with a specific brief to provide a type of illustration, he ensures that his distinct and somewhat mordant voice is enshrined within the textures of his imagery, whatever its more obvious purposes. Working within an industrialised market where the production of images could easily degenerate into the impersonal, he remains the outspoken auteur.

Related Material

Last modified 19 October 2012