Wehnert’s outspokenness is carried forward in visual interpretation and especially in his selection of scenes. ‘The moment of choice’, as Hodnett calls it (p.6) is a crucial decision for any illustrator and Wehnert’s are often unusual, presenting the viewer with unpalatable information which ranges from extreme states of mind to physical and mental suffering. He seems to view these moments as the texts’ core meaning, taking every opportunity to offer the reader a series of distilled versions of underlying tensions and conflicts.

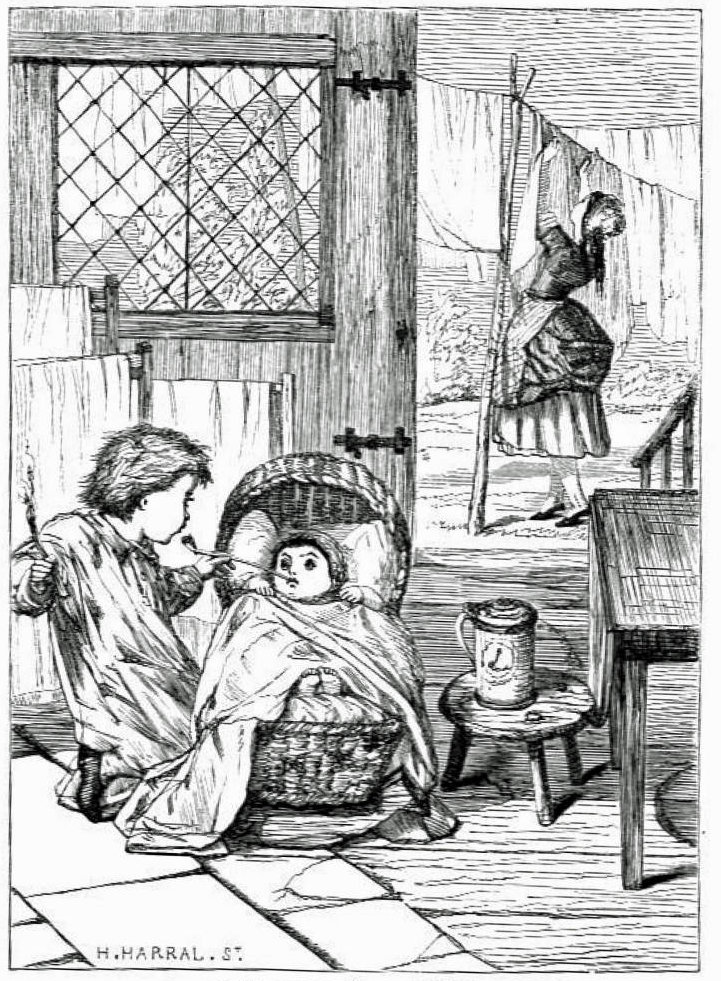

Tommy sets fire to the towels. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

In his designs for More Fun (1864), as in his image for Midsummer Eve, he focuses the moments where the action is at its most destructive. Again, literality takes its part: Mary Gillies writes in a dead-pan style of endless naughtiness, and Wehnert replicates her descriptions with blunt directness. In his response to ‘Tommy sets fire to the towels’ (facing p. 62) he provides a journalistic image of the boy with a torch in his hand, and holding a pipe to baby’s mouth. ‘How funny [he] would look, smoking …which made him cry again’ (p. 65). This is the very moment he chooses to show and we see it in unnerving detail, with Tommy on the loose, free to do whatever he wishes while the maid hangs the washing out, unaware of the danger within. Other images follow the same approach, and Wehnert heightens the author’s interest in disruption by showing intense depictions of scenes such as ‘Tommy thumped by the stool’ and ‘Rosa sees Amelia smashed’. Again, it is telling that he only shows the moments of maximum discordance; there are many others of repose and reconciliation, but it is the mischievousness, intensified to the point of sometimes repulsive violence, that concerns him. Remembering this is supposed to be a children’s book, the effect seems curiously at odds with its didactic purpose. The author reports her ‘fun’ ironically and moralistically, but the artist seems to relish in the chaos, compelling the viewer to contemplate scenes that celebrate cruelty rather than condemn it.

Such challenges recur elsewhere. In his designs for the Grimms’ Household Tales (1853) he focuses on the text’s grotesqueries, emphasising peculiar physiognomies and quaint but menacing settings. The result, as one critic observes, is finely poised: the illustrations impressively catch the authors’ ‘vital spirit of German legendary romance’ but are disconcerting, ‘remote, unreal, grotesque and suggestive; with strange bits of landscape and strange human faces’ (‘Reviews’, p.516). The recurrence of ‘strange’ and the emphasis on ‘remote, unreal’ points clearly to the sometimes dream-like or even nightmarish effects of this artist’s reading of even the most anodyne of material. When it comes to the more challenging texts, moreover, he is able to give full rein to his interest in extreme emotions and strange situations. Wehnert is probably at his most surprising in his illustrations of Romantic poetry by Keats, Coleridge, and Poe.

His fascination with the most ‘striking instance’ (The Gallery 1, p.54) is exemplified by his visualisation of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1858). Presented with dream-like material exploring anguish and the soul’s yearning for repose, Wehnert points to its sheer strangeness. Incongruities are stressed, it can be argued, through a process of calculated mirroring and replication. The weirdness of the initial encounter with the Ancient Mariner is powerfully conveyed in a dynamic composition of moving forms, and stranger still is the entirely literal showing the sailor belled by the albatross. Elsewhere, Wehnert depicts the narrator at various points of madness and despair, focusing on moments of self-examination and anguish by depicting his still face and inward gaze. Such contemplation similarly features in his illustrations for Robinson Cruscoe and in his single image for Byron’s Childe Harold (1855, plate 25). This interest in intense psychological conditions finds another expression in the work for Keats’s The Eve of St Agnes (1859), and is probably the artist’s best work.

Left to right: (a) Madeline praying. (b) St. Agnes’ Eve – Ah, bitter chill it was!. (c) Porphyro looking at the sleeping Madeline. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Issued in the form of a ‘dainty gift book’ (‘Illustrated Poems’, p.333), and historically significant as the first illustrated edition of this text, Wehnert’s interpretation of Keats unites his fascination with extreme states of mind, the grotesque, and his apparent desire to shock. Such a combination finds a perfect vehicle in the surfaces of Keats’s poem and here, if perhaps nowhere else, Wehnert is able to satisfy both his own and – as far as we might surmise – the writer’s purposes; arranged as a tableaux vivant which visualises Keats’s rich and sensuous imagery and maps the unfolding of the narrative, the illustrations closely respond to the details and situations of the text while embodying the artist’s characteristic techniques and interests.

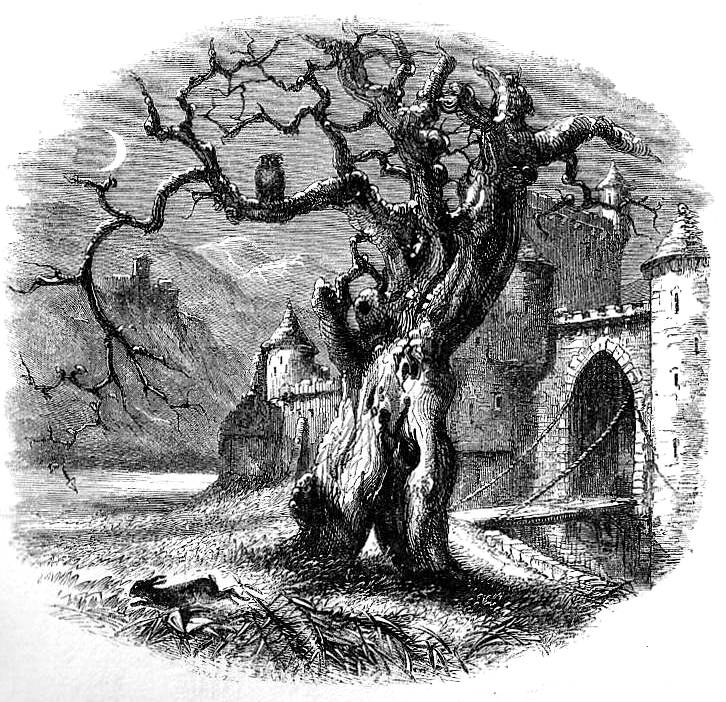

The opening design interprets the poem’s setting in terms of the grotesque. The image materially follows the textual specifications: the ‘bitter chill’ is registered in the frosty landscape; the limping hare scuttles by; and the owl, ‘a cold’ sits in the centre-ground (p. 7). But Wehnert stresses some images and invents others. He includes a gnarled tree which is implied but not specified, showing this as if it were a tree in a Gothic story, redolent of Poe. The effect is one of dislocation, placing the tale in the domain of the dream-like and preparing the reader for the strange events to follow. He also points to the poem’s eroticism, stretching the bounds of propriety by showing Porphyro as he parts the curtains and peeps at his beloved (p.2). The moment is greatly heightened by the intensity of his gaze: there is no question of the voyeuristic nature of his looking at Madeline and Wehnert stresses the implications of the encounter by highlighting her (feminine) passivity as opposed to his (masculine) forcefulness.

Such psychological extremes are developed throughout his illustrations for the poem. The artist challenges the reader/viewer to make sense of experiences that range from the erotic to the drunken, from the threat of violence to romantic escape. Faithful to the text, but creating an unconventional interpretation, his reading of Keats is characteristically outspoken.

Related Material

Last modified 19 October 2012