[The illuminated “T” is based on one of the drawings Thackeray created for Vanity Fair. — George P. Landow]

he 40 full-page etchings in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair provide a visual commentary on the written information. Viewed as a whole, they form a visual montage which establishes aspects of character, interrogates the narrative, and points to elements which are otherwise submerged within the written text. Poorly drawn, for the most part, and a source of huge difficulty for the untrained artist – who struggled with the technical aspects of drawing on wax and cutting the plate with acid – they are nevertheless a central part of Thackeray’s scheme of work.

A particular role, and one which has barely been noticed, is their function as a visual guide, helping the reader to navigate a pathway through the novel’s picaresque structure. Henry James was contemptuous of Thackeray’s ‘baggy’ narratives (iv), but if we read the illustrations in conjunction with the text (as the author intended) there is no difficulty in engaging with the story while simultaneously reflecting on its complications.

If we take the series as a whole, we can see how Thackeray used his distribution of scenes to point to the novel’s movement through a number of settings in London, Waterloo and Germany. Early critics noted its urban locales, but of the 40 etchings only 12 show exteriors; the remaining 28 are interiors. This focus is important because it stresses the smallness of the characters’ lives; their conspiracies and deceptions may have a universal application, but Thackeray uses the engravings to root the action in the everyday world of home. Most of the scenes, as the author notes in the Prologue, are ‘very middling indeed’ (viii), exchanges enacted within a domestic arena. The etchings privilege conversations and almost all of them show groups rather than individuals, social events, families at home, confrontations and other close exchanges. This emphasis suggests that ‘vanity’ is as much a product of society as it is of the ego on its own.

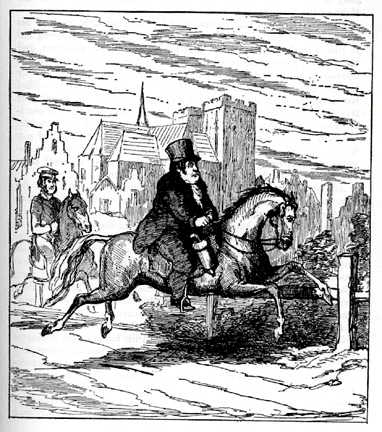

Figured as a series of interiors as stage-sets in which the characters enact their lives, the etchings stress the claustrophobia of their world by trapping them inside their walls as surely as they are trapped by the narrowness of their social milieu and the intricacies of their plotting. Yet the ‘outside’ is an important foil to the ‘inside’. In particular, the engravings act as a mean of ventilating the workings of the domestic scene by injecting a sense of the vital Regency world that lies outside and sometimes penetrates the closed rooms. Thackeray’s compositions are usually dynamic, providing a physical dimension to what is otherwise missing from the letterpress, which stresses dialogue and static description. Becky’s throwing of the dictionary is vividly represented in Rebecca’s Farewell (facing p.7), and the bustle of the contemporary scene is captured in An Elephant for Sale (facing p. 145) and Mr Jos Shaves off his Moustacios (f.p.279).

Left: Rebecca’s Farewell. Middle: An Elephant for Sale. Right: Mr Jos Shaves off his Moustacios. Click on images to enlarge them.

However, this approach is far from realistic. The action is shown as burlesque or slap-stick, and the comic vitality of each of these scenes complicates our responses by making us laugh when we should be appalled. Poor behaviour (such as Jos’s cowardice and Becky’s contemptuous pride) are given an ironic twist; the author reveals the ‘weaknesses, vanity and humbug of society’ (qtd. Critical Heritage, p. 58), but blends it with sarcasm (p.18). The mismatch between the dead-pan commentary of the text and the physical humour of the etchings is a central part of Thackeray’s visual/verbal technique, and it is difficult to sympathise with any of the characters on the basis of their visual representation; Thackeray presents his work as a ‘novel without a hero’, and his large illustrations maintain a distancing irony, the mechanism and focus of sour comedy.

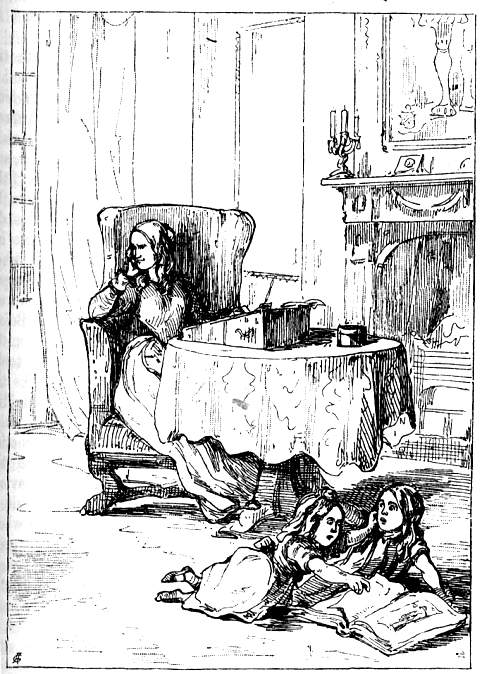

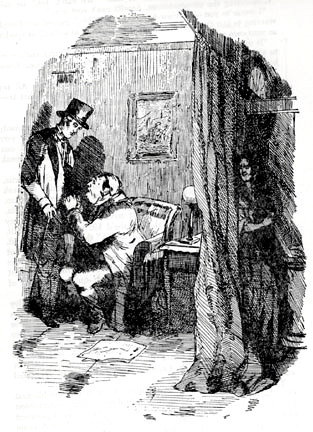

At the same time, he manipulates his images to suggest the disruptive influence of the vain and foolish. This is subtly conveyed in the plates of Rebecca. As noted earlier, Thackeray describes her as beautiful but depicts her as witch-like, and the implications of her behaviour is more closely suggested by showing her as a still figure surrounded by disorder. In Miss Sharp in her School-Room (facing p.80), the contrast between the fighting children and her indifference suggests the chaos she always brings with her. Becky is notably associated with barriers – walls, windows, doors and curtains – which act as a visual metaphor for her dishonest character and the uncertainty of our perceptions. In A Family Party at Brighton (facing p. 213), she is placed on a balcony talking to George; her dishonourable intentions are suggested in her sly gaze (an expression repeated in all of her portraits), while the rest of the action is glimpsed through the open door; Amelia looks out anxiously. Likewise in Becky’s Second Appearance in the Character of Clymenestra (facing p.623), she listens to Dobbin’s conversation with Jos from behind a screen, plotting her murderous next move.

Left: Miss Sharp in her School-Room. Middle: A Family Party at Brighton. Right: Becky’s Second Appearance in the Character of Clymenestra. Click on images to enlarge them.

Other characters are presented in the same unsympathetic way. Thackeray mocks the weakness of Jos Sedley, who is described in the written text as overweight and self-indulgent:

His bulk caused Joseph much anxious thought and alarm; now and then he would make a desperate attempt to get rid of the superabundant fat; but his indolence and love of good living speedily got the better of these endeavours at reform … [19].

In the illustrations this disparagement is taken much further. Thackeray deploys the traditional visual trope which equates obesity with stupidity while expressing moral slackness in the form of Jos’s large and ponderous body. Jos the gullible fool is memorably shown in the Mr Joseph entangled (f.p. 32), his huge bulk dominating the composition as he allows Becky to ensnare him in cat’s cradle as surely as she tries to trap him with her sexuality. The image gains strength from its connection with the initial letter in which Becky tries to catch her fat fish on a fishing line, an issue explored by Matt Maguire. Jos is at his most absurd, however, when he tries to flee Waterloo. Mr Jos shaves off his mustachios (fp 279) shows him escaping on what seems a rocking-horse rather than a real one, his weight crushing his steed: a sharp comment on both his cowardice and his petulance, as if he were a school-boy playing on his toy horse. Such mockery provides a refracted view of the travails of the real cavalry, cut down, like George, on Waterloo field.

Mr Joseph entangled. Click on image to enlarge it.

The full-page engravings are used, in short, to embody the changing locales, to focus the characters’ machinations in limited domestic interiors, and to suggest their moral nature. The effect is generally a matter of absurdism, a world of buffoons and fairy-tale women. The apparently unsophisticated nature of the drawing is a counterpoint to the glittering urbanity of Thackeray’s written satire, and, as noted earlier, the author creates a calculated dissonance between the two. Ultimately, the reader/viewer is asked to engage in an act of double-cognition in which the characters are baldly shown in grotesque figure drawing, forcing us to read them as actors in a pantomime, with all of its implications of vulgarity and suffering. At the same time, the naïve style casts the characters as children in a play, a visual conceit cruelly at odds with Becky’s adultery and Jos’s cowardice. The effect is analogous to the mock-heroic, though this time experience is apparently described through the medium of innocence, as if it were a raconteur’s tale re-told in childish cartoons. Such complicating of our responses is typical of Thackeray’s deployment of the relationships between his words and illustrations – unsettling the interpreter who expects only a confirmatory interaction, and putting in its place a rich sense of bitter incongruity.

Related material

- William Makepeace Thackeray and Book Illustration

- Style and Purpose

- Thackeray's Christmas Books

- Thackeray’s Illustrations for Vanity Fair (I)

Works Cited

James, Henry. Preface to The Tragic Muse. NY: Scribner, 1980. ].

Thackeray, W. M. Vanity Fair. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849 [this is a reprint of the first edition, retaining the same pagination].

Thackeray: The Critical Heritage. Eds. Geoffry Tillotson & Donald Hawes. London: Taylor & Francis, 2003.

Created 20 January 2014