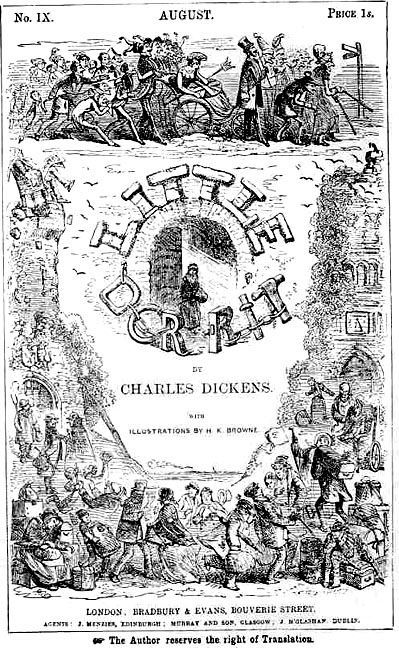

Cover for monthly parts of "Little Dorrit," August 1856 (Part IX)

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

1855

Wood engraving

Illustrated wrapper for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Part IX (August 1856).

Source: Steig, plate 103.

[Return to text of Steig]

The book was published in the customary twenty monthly parts, December 1855 through June 1857, by Bradbury and Evans with a blue wrapper and forty plates designed by Phiz.

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

Commentary

Whereas millions of purchasers of the novel in volume form, beginning in June 1857, have had the opportunity to study Phiz's forty illustrations for Little Dorrit, placed immediately adjacent to the passages they realise, the thousands — Robert L. Patten notes that the opening circulation was 38,000 (216) — who purchased the monthly parts had the disadvantage of not encountering the two illustrations for each monthly-part thus juxtaposed. However, each regular serial instalment purchaser encountered nineteen times the blue-green monthly wrapper with its implicit commentary on the novel. At each successive monthly purchase, the serial reader re-considered the wrapper, studying how its design reflected upon chapters already read and pondering how the complicated design was a key to future chapters, although this design, unlike that for A Tale of Two Cities, is emblematic and does not enshrine certain scenes in the plot. The allegorical figures on the monthly wrapper are often ambiguous in their meaning, although the goddess Britannia, symbolic of Great Britain and British society, in the centre of the upper register, is obvious enough with her helmet, shield, and chariot. The book's title in bricks and chains makes manifest the connection between the female protagonist (centre, surrounded by the words) and the Marshalsea Prison in the Borough, immediately south of London Bridge. Two other recognizable figures are Jeremiah Flintwinch and Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, lower right.

Like Bleak House, Little Dorrit depends for a great part of its effectiveness upon Dickens' translation of his social vision into symbolic vision: Mrs. Clennam's paralysis, the parasitic Barnacles, Mr. Merdle's banality of evil, and perhaps above all, the motif of the prison. The successes and failures of collaboration depend partly on Dickens' assignment of subject, and partly on Browne's execution of each subject. Like all the monthly serial novels from Nicholas Nickleby onward, this one begins with a cover design intended to embody the novel's main themes; and like Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and perhaps more arguably, David Copperfield and Bleak House, Little Dorrit ends in the monthly parts and thus opens in the bound edition with a complementary pair of etchings that serve both as foreshadowing and retrospective devices. The cover design is more unified than Bleak House's, and quite a bit less specific as to individual characters. John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson discuss this cover in some detail in Dickens at Work (pp. 224-26), but Browne's original drawing was not available to them, and it reveals differences with the final plate which shed some light on the points they discuss. This drawing is part of a set of Browne's drawings for Little Dorrit, formerly in the collection of the late Comte de Suzannet; the set was put up for auction with the rest of the Suzannet collection in 1971, but not sold; subsequently it was stored in the Dickens House. I am grateful to Dr. Michael Slater, editor of The Dickensian, and Miss Marjorie Pillers, curator of the Dickens House Museum, for the opportunity to examine these drawings in 1972, and to the late Comtesse de Suzannet for permission to photograph several of them. Since then, they have been sold to a collector who will not permit their reproduction). First, Butt and Tillotson speculate on whether the original design carries the originally intended title, "Nobody's Fault"; they remark that this would have an ironic effect in connection with the political and social details that are depicted. In fact the drawing bears the published title, executed almost precisely as in the cut, with letters of stone and chain. In the center, Amy Dorrit stands at the outer gate of Marshalsea Prison, just having emerged from within; Butt and Tillotson comment that she stands "in a shaft of sunlight," but do not note that this sunlight — which here, as in the etched title page, lends a sanctified air to Amy — comes from within the prison, and that in a sense Amy goes into a world much darker than the prison. When it is repeated on the title page, this image is in turn complemented by the novel's frontispiece.

The "political cartoon" (as Butt and Tillotson call it) across the top, showing the blind and halt leading a dozing Britannia with a retinue of fools and toadies, is largely the same in the drawing, but one important detail differs in the extension of this motif down the sides of the design, while others are developed more clearly in the actual woodcut. The crumbling castle tower is in the drawing, as is the man sitting precariously on top of it, a newspaper in his lap and a cloth over his eyes, oblivious of the deterioration of the building. But while in the cut the church tower is clearly ruined, with a raven (or jackdaw?) atop it, the ruin is less evident in the drawing, and on the tower we have a fat, bewigged man asleep on an enormous cushion; this looks like something out of the Bleak House cover, since the cushion is probably meant to be the woolsack, and the man a high member of the legal profession. I suspect that Dickens told Browne to remove him, as his place on the church is inappropriate. The black bird in the cut would seem to signify the general decay of Victorian society and the prevalence of death, or, if it is a jackdaw, the thievery of institutions; yet I cannot find it any more appropriate to the church. The child playing leapfrog with the gravestones, a concept we have earlier traced back to Browne's frontispiece for Godfrey Malvern, here underlines the theme of indifference and irresponsibility. One other alteration likely to have been at Dickens' insistence is the representation of Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, with Flintwinch standing alongside, In the drawing we see instead, from the rear, a woman in a bath chair, pushed by a man. Dickens probably wished to have a more particular representation of Arthur's mother, as she and Jeremiah have a malevolent appearance in the cut and stand out as the only other definite characters, apart from Amy.

Little Dorrit's cover is effective in conveying certain themes — decay, indifference, irresponsibility of government, and confusion — as well as foreshadowing major tonalities of the novel, such as the dark prison, Little Dorrit as central figure, and Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch as evil genii presiding over the ramifications of the plot. Along with the Bleak House cover it is the most socially conscious of the designs, and presents its ideas more directly than its predecessor. Dickens must have supplied a good deal of direction for this wrapper, given that the date of the following letter (19 October 1855) is approximately six weeks before the publication date of Part 1:

Will you give my address to B. and E. without loss of time, and tell them that although I have communicated at full explanation length with Browne, I have heard nothing of or from him. Will you add that I am uneasy and wish they would communicate with Mr. Young, his partner, at once. Also that I beg them to be so good as send Browne my present address (N, 2: 698) [Steig, 159-161]

Related Material

- Taking Off the Wrapper: David Copperfield Anticipated, May 1849.

- Hardy, Dickens, Serialisation, and Illustration: A Rebuttal of Alan S. Watts' "Why Wasn't Great Expectations Illustrated?"

- A Note on Phiz's Wrapper Design for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) in Monthly Serialisation

- Marcus Stone's August 1864 Wrapper for Our Mutual Friend

- "Taking The Wrappers Off" — A Brief Overview of the Covers for the Monthly Serials Published by Charles Dickens, April 1836 to September 1870

- Positioning of Illustrations in Dickens's Novels and The Composition of the Wrappers

References

Cohen, Jane R. "Dickens and His Principal Illustrator, Hablot K. Browne." "Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz")." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 60-122.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ["Phiz"]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Authentic Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1867 edition]. Vol. 12.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. Oxford: Clarendon Press: 1978.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Next

Last updated 27 April 2016