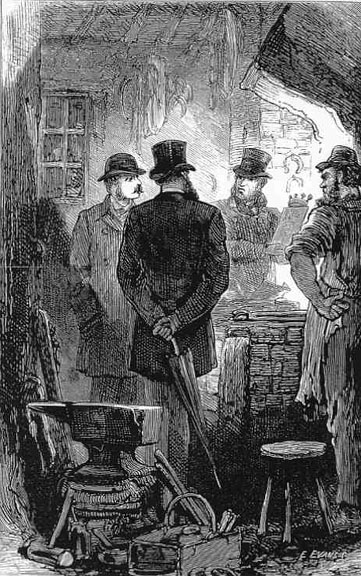

In the Smithy at Endelstow

James Abbott Pasquier

July 1873

Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes, Tinsley's Magazine, chapters 37-40, XII, 374

11.4 x 17.6 cm

[See commentary below]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

In the Smithy at Endelstow

James Abbott Pasquier

July 1873

Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes, Tinsley's Magazine, chapters 37-40, XII, 374

11.4 x 17.6 cm

[See commentary below]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"In the Smithy at Endelstow" [p. 374 in Penguin edition] is a condensed version of "Then he unfolded a piece of baize: this also he spread flat on the paper. The third covering was a wrapper of tissue paper, which was spread out in its turn. The enclosure was revealed, and he held it up for the smith's inspection." from serial chapter 40 (the last of four in the July 1873 instalment).

Hardy can maintain the story's suspense, which the final illustration tends to sustain rather than undermine by revealing too much either through its composition or its caption. Through a layered narrative Hardy gradually reveals first the fact of Elfride's death and then its circumstances. However, only in 1912, some four decades after initial volume publication of the novel, did Hardy add the significant detail of Elfride's having died as the result of a miscarriage. Even in 1886, Hardy felt that he had to treat this delicate subject obliquely when describing Lucetta's death after the Skimmington in The Mayor of Casterbridge--although after her epileptic seizure and Henchard's message to Farfrae that his wife is "ill" the narrator finally specifies the malady as a "miscarriage" at the close of Ch. XL in the volume edition, in the serial text her condition is merely described as a "dangerous illness" (The Graphic, 1 May 1886: 478).

We encounter the final plate in Pasquier's series for the magazine on the page facing the beginning of Ch. 37, "After Many Days," which cursorily follows Knight around Europe as he vainly attempts to obliterate any trace of the memory of his final parting from Elfride and her father in his legal offices at Bede's Inn, London, in Ch. XXXV. As the novel's final instalment in Tinsley's Magazine begins, each lover is still in at least partial ignorance as to his own and the other's circumstances. Knight is unaware that Stephen was "the other man" to whom Mrs. Jethway had alluded in her malicious letter; Stephen is "Totally ignorant whether or Knight knew of his own previous claims upon Elfride" (Ch. 37, Penguin 350). That Knight never knew of his quondam engagement to Elfride and consciously betrayed their friendship by courting her Stephen does not learn until he and Knight have re-established their relationship. Although Hardy permits each suitor to learn the full extent of each other's degree of attachment early in this final instalment, and of Elfride's untimely death away from home in Ch. XXXIX when Mr. Swancourt joins the cortège, that she died the wife of Lord Luxellian they (and we) do not learn until the last chapter, at the very textual moment to which the eleventh illustration points.

The details, in fact, are not provided until Stephen and Knight--again, by accident, as with the reading of the coffin-plate in the smithy earlier--hear Elfride's story from the land-lady of the Welcome Home Inn, Unity Cannister, who had been Elfride's maid at the Endelstow rectory and subsequently at The Crags. That a member of the class to which Rev. Swancourt aspires has the final claim upon Elfride Pasquier asserts by depicting the coffin-plate and baronial coronet as the focal point of the final illustration. Taking shelter from a sudden shower in the outer chamber of the smithy, the reunited friends witness the delivery of a mysterious package by an agent from Stanton. Gradually the wrappings of paper, baize, and tissue are removed to reveal what the blacksmith must affix to the coffin. The illustration is thus completed by the inscription in Old English letters (conveniently unreadable in Pasquier's representation of the coffin-plate), the two moments, visual and textual, separated by many pages of paper which the reader must peal back. Hardy maintains his dualistic perspective which has excluded Elfride's since the scene in Knight's chambers in Bede's Inn, London, in Chapter 36: “The undertaker's man, on seeing them look for the inscription, civilly turned it round towards them, and each read, almost at one moment, by the ruddy light of the coals” (Ch. 40, Penguin 375). As the light of the forge flares up behind the coffin-plate and baronial coronet (as in the letter-press pages later), the halo of "the yellow glow" signifies the mental illumination that this moment signifies for the former suitors.

Pasquier supplies realistic details that enforce the viewer's belief in the depiction of the culminating moment in the lives of Stephen Smith and Harry Knight (Elfride having experienced her culminating moment off-stage, so to speak). The scene's verisimilitude is established by the brawny, exposed arm, crushed workman's hat, and blackened apron of the smith, contrasting the respectably clad middle-class gentlemen: the undertaker's man (right of centre); Stephen Smith (left), distinguished by moustache, bowler hat, and business suit; and Harry Knight (centre) with beard, tail-coat, top hat, and umbrella. The last article recalls the beginning and ending of his relationship with Elfride in the visual text: the walking stick which he flourishes in plate five (January 1873) on Endelstow Tower and holds (again in a gloved hand) in the nave of the church in the tenth (June 1873). Indeed, the artist has provided us with a plate full of "carefully-packed articles" (Ch. 40, Penguin 375) that reify the lower-middle class social context of the moment that reveals Elfride as neither Stephen's trophy in his social climbing nor Knight's delightful prop as a complement to his professional and literary life. Gradually, while a "yellow glow" suffuses Elfride's marks of social distinction, "the chill darkness" of their ignorance of the real Elfride envelops the lawyer and the architect. The baronial coronet, appraised by the expert iron-worker "as fine a bit of metal-work as [he has] ever see[n]," stands for Elfride's victory over the social and emotional isolation which the censorious Mrs. Jethway and the morally scrupulous Knight attempted to impose upon her. Both have been men "in the dark" (Chapter 40, Penguin 372) in asserting their claims to her as their "darling," for the plaque and coronet make palpable her final identity as another's. She has exchanged a Smith and a Knight for a Lord. Her life-story, like the inscribed plaque, is "beautifully finished," for she dies a surrogate mother, valued companion, and cherished wife, rather than an object of rivalry. That it has "cost some money" recalls Stephen's attempt to transcend class-barriers by amassing a fortune in India in order to render himself an eligible suitor in Christopher Swancourt's eyes.

As the male-produced canvas-and-oil painting of the Duchess of Ferrara have supplanted the insistently feminine presence of the young noblewoman in Robert Browning's "My Last Duchess"(1842; text and commentary), so the finely-worked decorative plaque and coronet have effectively replaced the living Elfride and fixed her status as a member of the peerage. Like her form and features objectified in the title as "a pair of blue eyes" in life, the beautiful and costly plaque (her final presence in the novel) is an object of male observation, appraisal, and admiration. The coronet and coffin-plate that have "cost some money" assert her superior status in a manner that the commodity-conscious middle-class males gathered around the forge can fully appreciate, as the extension of a socially superior, "propertied" aristocrat who has purchased for her a conspicuously expensive ritual that even that scion of the nobility Henry Knight would not have been able to afford.

The horse-shoes above the plaque (perhaps implying Elfride's luck in making a socially advantageous marriage), the soot-darkened window (consonant with the enclosing shades of death), the harness, the vent above the blacksmith, the massive anvil, sledge hammer, crude stool, chains, and basket full of iron-working implements all suggest that Pasquier devoted considerable thought and some research into the composition of this final illustration. Ironically, these carefully drawn workaday objects are more insistently real that the accoutrements of wealth and privilege (such as the elegant balustrade in the first plate and the magnificent barouche in the fourth) that occasionally appear in the plates of this uncomfortably classified "novel of manners." These humble but highly functional tools are the objective correlatives of Stephen Smith's social background, the plain-speaking Smiths and their friends, whose dialect strikes a truer chord than the ponderous philosophizing of Henry Knight and the socially pretentious chatter of the Swancourts, but whom James Abbott Pasquier, Thomas Hardy's first serial illustrator, neglected to depict at all in his visual program for the first of Hardy's novels to be published under his own name.

Last modified 14 August 2003