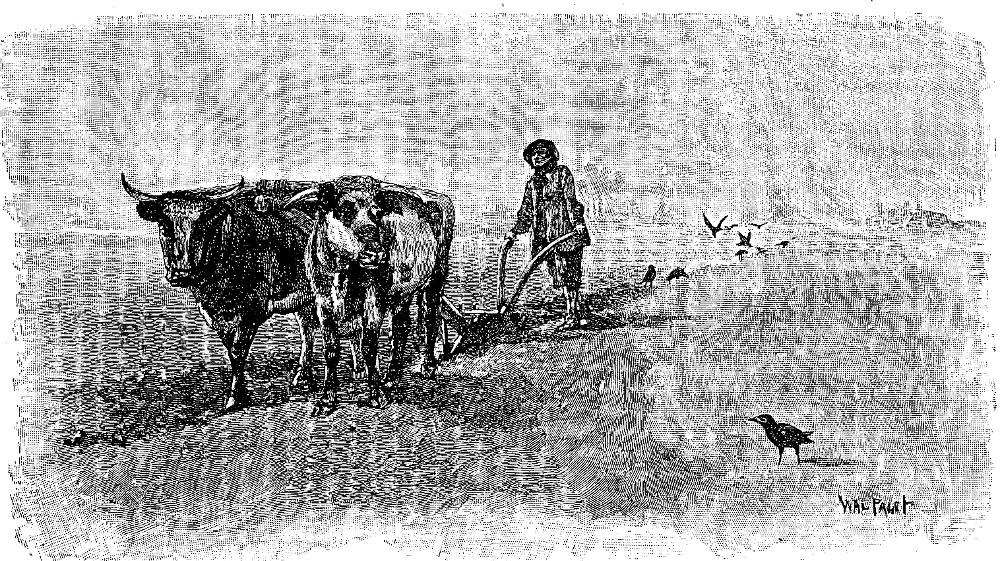

"I farmed upon my own land." (See p. 222), signed by Wal Paget, bottom right. In the headnote vignette for the second part of the novel, Paget has positioned the ploughing scene in such a way as to suggest that Crusoe finds the drudgery of farming in Bedfordshire comparable to that of struggling to survive on the island. Top half of page 219, roughly framed: 6.9 cm high by 12.7 cm wide. Running head: "Settling Down" (page 221).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Crusoe short-lived existence as a farmer

I farmed upon my own land; I had no rent to pay, was limited by no articles; I could pull up or cut down as I pleased; what I planted was for myself, and what I improved was for my family; and having thus left off the thoughts of wandering, I had not the least discomfort in any part of life as to this world. Now I thought, indeed, that I enjoyed the middle state of life which my father so earnestly recommended to me, and lived a kind of heavenly life, something like what is described by the poet, upon the subject of a country life: —

“Free from vices, free from care, Age has no pain, and youth no snare.” [Part Two, Chapter I, "Revisits the Island," page 222]

Commentary

Having returned to England, Crusoe immediately sets out for Lisbon to visit the Portuguese sea-captain who picked him up three decades earlier off the African coast. The presentillustration on the first page of the sequel occurs prior to the scene in which he quarrels with his wife about re-visiting the island. Just after this passage, Crusoe's announces his wife's death, which then propels him and Friday into further adventures abroad, despite his being sixty-one, an age at which he freely admits that he should "have been a little inclined to stay at home, and have done venturing life and fortune" (p. 219). Fortunately for the reader, he is not. Like Alfred Lord Tennyson's Ulysses in the 1842 dramatic monologue, Crusoe finds to his own dismay that he "cannot rest from travel" (line 6).

Nearly thirty years after the initial Cassell edition, Paget presents an even more disturbing psychological portrait of Crusoe and his wife, for they actually seem to be arguing about the possibility of his returning to the island. In the earlier illustration simply entitled Crusoe Married, the returned and presumably retired adventurer stares into the fire (left) as his wife studies him, troubled by his wander-lust. Paget does not provide such contextual clues to the nature of Crusoe's home-life "It was all to no purpose.", but shows that, despite his affluence and comfortable home (merely suggested by the window-panes and the clothing worn by the couple), he finds something lacking and takes no joy in his farming — or his marriage.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 28 March 2018