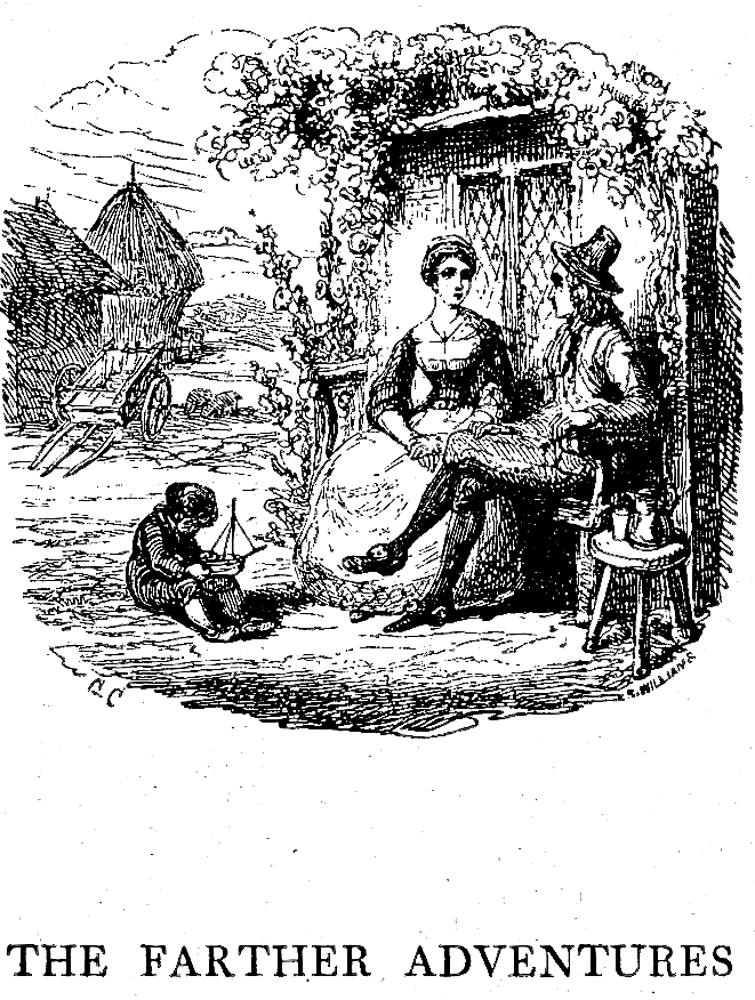

Crusoe married (page 205) — the volume's fifty-fourth composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Part II, The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Chapter I, "Revisits Island." Half-page, framed: 13.7 cm high (including caption) x 14 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated

But to return to my story. In this kind of temper I lived some years; I had no enjoyment of my life, no pleasant hours, no agreeable diversion but what had something or other of this in it; so that my wife, who saw my mind wholly bent upon it, told me very seriously one night that she believed there was some secret, powerful impulse of Providence upon me, which had determined me to go thither again; and that she found nothing hindered me going but my being engaged to a wife and children. She told me that it was true she could not think of parting with me: but as she was assured that if she was dead it would be the first thing I would do, so, as it seemed to her that the thing was determined above, she would not be the only obstruction; for, if I thought fit and resolved to go — [Here she found me very intent upon her words, and that I looked very earnestly at her, so that it a little disordered her, and she stopped. I asked her why she did not go on, and say out what she was going to say? But I perceived that her heart was too full, and some tears stood in her eyes.] “Speak out, my dear,” said I; “are you willing I should go?” “No,” says she, very affectionately, “I am far from willing; but if you are resolved to go,” says she, “rather than I would be the only hindrance, I will go with you: for though I think it a most preposterous thing for one of your years, and in your condition, yet, if it must be,” said she, again weeping, “I would not leave you; for if it be of Heaven you must do it, there is no resisting it; and if Heaven make it your duty to go, He will also make it mine to go with you, or otherwise dispose of me, that I may not obstruct it.”

This affectionate behaviour of my wife’s brought me a little out of the vapours, and I began to consider what I was doing; I corrected my wandering fancy, and began to argue with myself sedately what business I had after threescore years, and after such a life of tedious sufferings and disasters, and closed in so happy and easy a manner; I, say, what business had I to rush into new hazards, and put myself upon adventures fit only for youth and poverty to run into? [Part Two, Chapter I, "Revisits the Island," pp. 206-7]

Commentary

Defore published The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe almost immediately after the first novel, and during the Victorian era it appeared as "Part Two." The present illustration marks the transition between the two parts of the narrative, for it occurs at the tail end of the first part, but realizes Crusoe's description of his married state at the beginning of the second. Like Alfred Lord Tennyson's Ulysses in the 1842 dramatic monologue, Crusoe finds to his own dismay that he "cannot rest from travel" (line 6).

Crusoe himself stares into the fire (left) as his wife studies him, troubled by his wander-lust. The fashionable clothing, the comfortable domestic interior, and the handsome woman seated across the table from him seem to mean nothing to the middle-aged Crusoe. The embedded portrait of a woman holding a parasol (upper left) must have far different associations for Crusoe as it serves as an objective correlative for his years on the island under a tropic sun, against which he protected himself with a goatskin umbrella. The cat at his feet counterpoints Crusoe's unease; the candle burning between the couple suggests that this is an after-dinner or evening discussion, and that its subject is a familiar theme in their dialogues. Despite his affluence and comfortable life style, which the blooming roses in the bottom border suggest, he finds something lacking. Nearly thirty years later, Paget presents a more disturbing psychological portrait of Crusoe and his wife arguing about the possibility of his returning to the island.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from the other 19th c. editions, 1831 and 1891

Above: George Cruikshank's realisation of Crusoe's bucolic idyll, Crusoe, his wife and child on their farm in Bedfordshire (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Wal Paget's lithograph revealing Crusoe's depression at not having the stimulus of combat and travel, "It was all to no purpose." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 24 March 2018