Dancing round the fire (p. 144) does not depict Crusoe but may convey something of Crusoe's perspective through the telescope. Crusoe (now without his faithful canine companion) from a safe distance takes stock of his enemy. The contemporary, realistic appearance of the lithographic vignette makes it seem like a true-to-life photograph, like the representations of African tribesmen within the pages of the Illustrated London NewsMiddle of page 145, vignetted: 10.5 cm high by 11.7 cm wide, signed "Wal Paget" lower left. Running head: "Encounter with the Savages" (p. 145).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Ritual Dancing around the Fire on the Beach

About a year and a half after I entertained these notions(and by long musing had, as it were, resolved them all into nothing, for want of an occasion to put them into execution), I was surprised one morning by seeing no less than five canoes all on shore together on my side the island, and the people who belonged to them all landed and out of my sight. The number of them broke all my measures; for seeing so many, and knowing that they always came four or six, or sometimes more in a boat, I could not tell what to think of it, or how to take my measures to attack twenty or thirty men single-handed; so lay still in my castle, perplexed and discomforted. However, I put myself into the same position for an attack that I had formerly provided, and was just ready for action, if anything had presented. Having waited a good while, listening to hear if they made any noise, at length, being very impatient, I set my guns at the foot of my ladder, and clambered up to the top of the hill, by my two stages, as usual; standing so, however, that my head did not appear above the hill, so that they could not perceive me by any means. Here I observed, by the help of my perspective glass, that they were no less than thirty in number; that they had a fire kindled, and that they had meat dressed. How they had cooked it I knew not, or what it was; but they were all dancing, in I know not how many barbarous gestures and figures, their own way, round the fire.[Chapter XIV, "The Wreck of the Spanish Ship," pp. 143-144]

Commentary: The Arrival of the Cannibals

Whereas George Cruikshank's dancing Negroes in his 1831 title-page vignette do not seem much more than cavorting caricatures or pantomime cannibals, Paget has taken his subject seriously and attempted to depict Defoe's natives with relentless accuracy — but they resemble African tribesmen rather than Carib Indians,the indigenousCaribbean people of the Lesser Antilles related to the aboriginal inhabitants of theSouth American mainland. Although Paget has paid strict attention to Defoe's description of Friday, he has given the dancers the hair and features, as well as the clothing and skin colour, of tribesmen armed with shields and spears. Paget may have in mind the Zulu, whose wars with the British in South Africa made them a household word in Great Britain from the 1870s onwards. The illustration may recall two noteworthy encounters: the disastraous defeat of British forces at Fugitives' Drift (1879) and the epic defence of the garrison at Rorke's Drift, in which a hundred and fifty British and colonial troops held off a protracted assault by three thousand Zulu warriors. However, the shield carried by the warrior left of centre is not a match for the cowhide shields of the Zulu, and the weapons carried by the dancers are not assegai.

With other programs of illustration before him, Paget followed his inclination to focus on the protagonist's salvaging goods from the wreck rather than show the wreck itself — and indeed the wreck is nowhere in sight. The parallel scenes in the earlier Cassell edition show both the beached Spanish galleon and Crusoe in his boat, asleep after his salvage expedition and the boat fully loaded. The effect is to raise the reader's anxieties about Crusoe's safety as Paget shows another canoe-load of eight natives arriving (upper left), and another eight already dancing around the fire.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Related Scenes from Stothard (1790), Phiz (1864), the 1818 Children's Book, Cruikshank (1831), Cassell's (1863-64), and Gilbert (1867)

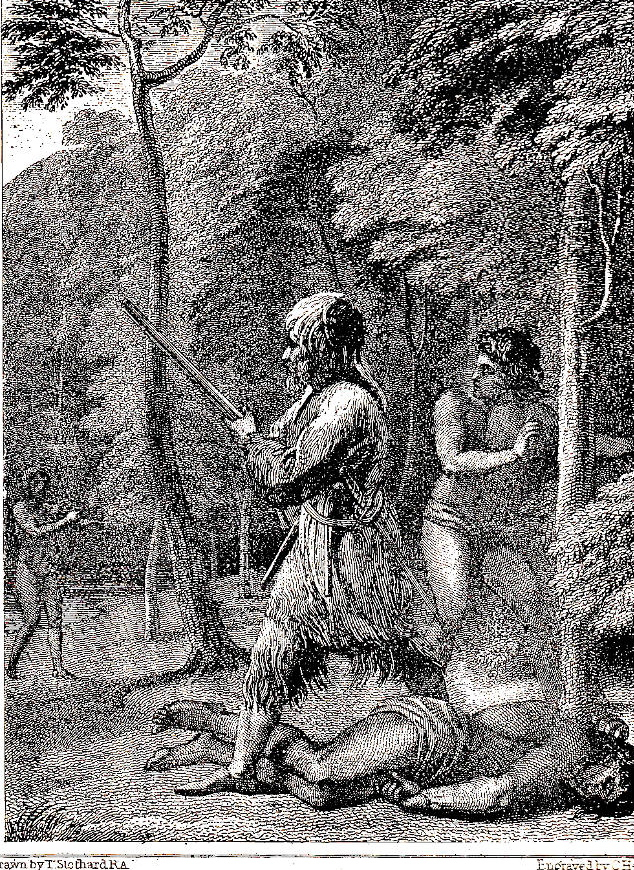

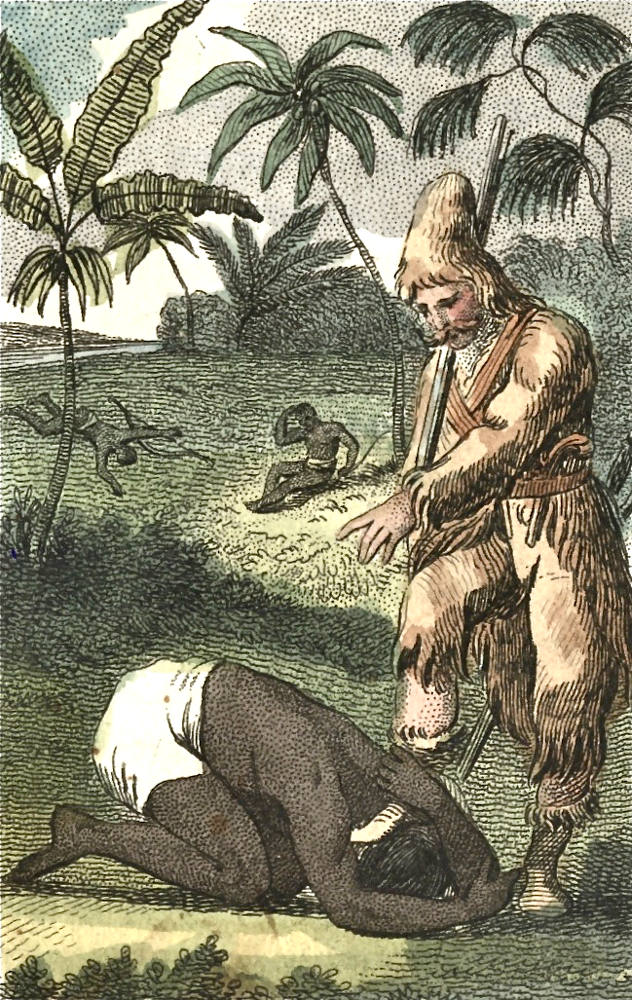

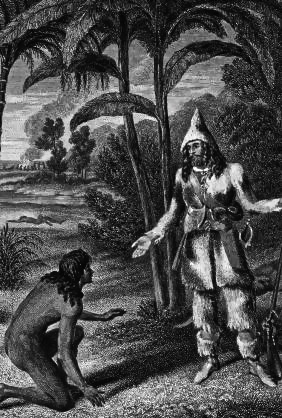

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the rescue scene, an illustration of which Cruikshank was probably aware, Robinson Crusoe first sees and rescues his man Friday (copper-plate engraving, [Chapter XIV, "A Dream Realised"). Centre: Phiz's steel-engraved frontispiece, with the surviving pursuer about to attack the unwitting Crusoe, Robinson Crusoe rescues Friday (1864). Right: Colourful realisation of the same scene, with a decidedly subservient and Negroid Friday: Friday's first interview with Robinson Crusoe. (1818). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Cruikshank's 1831 realisation of the rescue scene, Crusoe having just rescued Friday (frontispiece, Volume I). Centre: Sir John Gilbert's realisation of the rescue scene, Crusoe rescues Friday (1867?). Right: Realistic but emotionally muted realisation of the same scene, Crusoe and Friday (1863-64).

Above: The 1831 title-page vignette for the John Major edition, Cannibals dancing around a fire, appearing again near the section realised by George Cruikshank.

References

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 3 May 2018