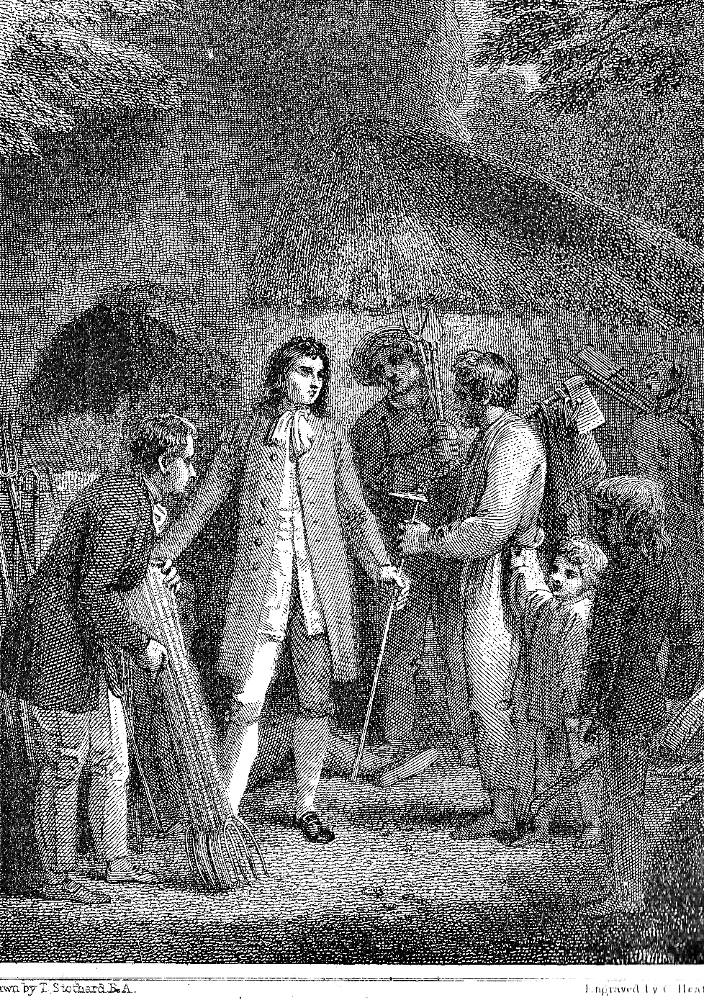

We walked on

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

lithograph

16.5 cm high by 7.9 cm wide, vignetted.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, embedded on page 301.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Crusoe and the Catholic Priest walk to Atkins' Plantation

I was sensibly touched with this discourse, and told him his inference was so just, and the whole design seemed so sincere, and was really so religious in its own nature, that I was very sorry I had interrupted him, and begged him to go on; and, in the meantime, because it seemed that what we had both to say might take up some time, I told him I was going to the Englishmen’s plantations, and asked him to go with me, and we might discourse of it by the way. He told me he would the more willingly wait on me thither, because there partly the thing was acted which he desired to speak to me about; so we walked on, and I pressed him to be free and plain with me in what he had to say. [Chapter VI, "The French Clergyman's Counsel," page 298]

Commentary

The other figure in the illustration, an undeniable presence, is the jungle setting of the conversation, perhaps based on a similar illustration in the 1864 edition, Crusoe and the Priest. The illustration combined with the evangelical text may have reminded late Victorian readers of how Natural Law (as exemplified by Charles Darwin's "Survival of the Fittest") had come into collision with Christian doctrine in 1859 with the publication of Origin of Species. The French priest seems to be advocating a middle ground in terms of European colonists' mating with indigenous women, since he has adopted the position that it is better for a young man and woman of different backgrounds to marry, even if the union transgresses the boundaries of race or class. This was an issue that Dickens would dramatise that same year that the Cassell's volume appeared in the relationship of lower-class Lizzie Hexam and the attorney Eugene Wrayburn in Our Mutual Friend (1864). As Charlotte Brontë in Jane Eyre points out, the Caribbean colonies of France and England tended facilitate miscegenation in in the kinds of European-Creole liaisons that polite society back in Europe did not readily accept — Bertha Mason and Edward Rochester being a case in point. Sexual desire, as the 1848 novel dramatises, was a significant cultural factor in the European colonisation of the West Indies, Africa, India, and Asia.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from Stothard (1790), Cruikshank (1831),and Cassell (1864)

Left: Thomas Stothard's study of Crusoe's distributing supplies to the colonists of both nationalities, Robinson Crusoe distributing tools of husbandry among the inhabitants. Centre: George Cruikshank's equivalent scene, Crusoe distributing agricultural implements. Right: The Cassell's parallel scene, a large-scale realisation of Crusoe's dialogue with the Catholic priest about marrying the colonists to native women, Crusoe and the Priest (1864). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

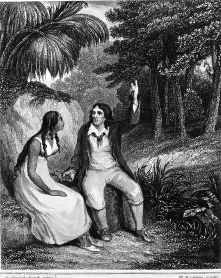

Above: Cruikshank's realisation of Crusoe's visiting Will and his wife, Crusoe presents a Bible to Will Atkins and his native wife (1831). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 3 April 2018