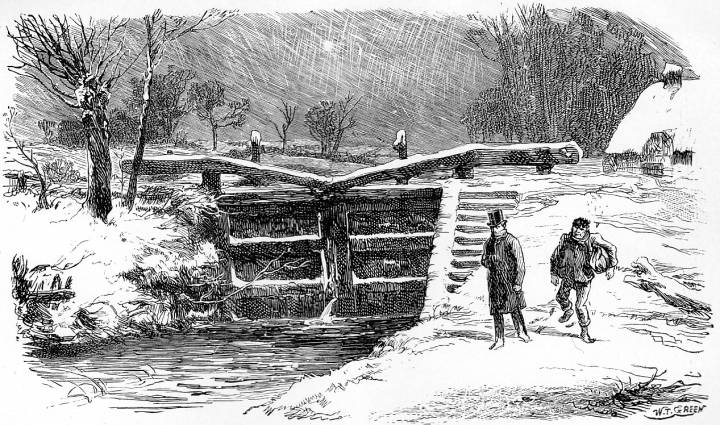

Not to be Shaken off by Marcus Stone. Wood engraving by W. T. Green. 9.5 cm high x 16 cm wide, vignetted. Last illustration for the nineteenth "double" monthly number of Our Mutual Friend, Chapter Fifteen, "What was Caught in the Traps that were Set," in the fifth book, "A Turning." The Authentic edition, facing p. 696. [This part of the novel originally appeared in periodical form in November 1865.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary

To complete the narrative-pictorial sequence and wind up the subplot involving Bradley Headstone and Rogue Riderhood, Marcus Stone takes us back to the Upper Thames lock at Plashwater Mill Weir, although the beautifully drawn lock is actually on the Regent's Canal (constructed from 1814-1820; modern photograph), near London.

Consider the plight of young Marcus Stone as Our Mutual Friend was winding up its serial run and his mentor, the greatest of the great Victorian authors, Charles Dickens, had fled to the continent to recuperate from the shock of the Staplehurst railway accident. Although Stone had had a relatively free hand, Dickens had been accustomed to inspect his drafts and make suggestions for revision. Now, as he prepared the novel's culminating illustrations, Marcus Stone lacked that resource. Instead of choosing a moment of great comedy by depicting Silas Wegg's receiving a richly deserved comeuppance at the hands of Sloppy, Stone had chosen a sentimental moment, Bella in the nursery with her baby. But one significant subplot remained — the blackmailing of Bradley Headstone by Rogue Riderhood, who has the clothes that the schoolmaster wore when, dressed like the waterman, he had attempted to murder Eugene Wrayburn. How should he proceed?

Other illustrators — notably Hablot Knight Browne— would have depicted the fierce struggle between the schoolmaster and his blackmailer on the very edge of the Plashwater Weir Mill Lock, but such a sensational scene, full of violent passion, was evidently not to Stone's less than melodramatic taste. Instead, he chose to create a highly realistic setting (modelled closely on the upper lock of the Regent's Canal, completed in August, 1820, in what is now the "Little Venice" of Maida Vale, one of central London's more exclusive residential areas) and place the adversaries in it moments before the schoolmaster's attack, thereby keeping the reader in suspense until the last possible moment. And, in the process, the realist has created an evocative landscape portrait: the Thames lock covered in snow, the very picturesque nature of which is foiled by the duel of relentless wills transpiring in the letter-press adjacent to it:

Bradley re-entered the Lock House. So did Riderhood. Bradley sat down in the window. Riderhood warmed himself at the fire. After an hour or more, Bradley abruptly got up again, and again went out, but this time turned the other way. Riderhood was close after him, caught him up in a few paces, and walked at his side.

This time, as before, when he found his attendant not to be shaken off, Bradley suddenly turned back. This time, as before, Riderhood turned back along with him. But, not this time, as before, did they go into the Lock House, for Bradley came to a stand on the snow-covered turf by the Lock, looking up the river and down the river. Navigation was impeded by the frost, and the scene was a mere white and yellow desert.

'Come, come, Master,' urged Riderhood, at his side. 'This is a dry game. And where's the good of it? You can't get rid of me, except by coming to a settlement. I am a going along with you wherever you go.'

Without a word of reply, Bradley passed quickly from him over the wooden bridge on the lock gates. 'Why, there's even less sense in this move than t'other,' said Riderhood, following. 'The Weir's there, and you'll have to come back, you know.'

Without taking the least notice, Bradley leaned his body against a post, in a resting attitude, and there rested with his eyes cast down. 'Being brought here,' said Riderhood, gruffly, 'I'll turn it to some use by changing my gates.' With a rattle and a rush of water, he then swung-to the lock gates that were standing open, before opening the others. So, both sets of gates were, for the moment, closed.

'You'd better by far be reasonable, Bradley Headstone, Master,' said Riderhood, passing him, 'or I'll drain you all the dryer for it, when we do settle.— Ah! Would you!'

Bradley had caught him round the body. He seemed to be girdled with an iron ring. They were on the brink of the Lock, about midway between the two sets of gates.

'Let go!' said Riderhood, 'or I'll get my knife out and slash you wherever I can cut you. Let go!'

Bradley was drawing to the Lock-edge. Riderhood was drawing away from it. It was a strong grapple, and a fierce struggle, arm and leg. Bradley got him round, with his back to the Lock, and still worked him backward.

'Let go!' said Riderhood. 'Stop! What are you trying at? You can't drown Me. Ain't I told you that the man as has come through drowning can never be drowned? I can't be drowned.'

'I can be!' returned Bradley, in a desperate, clenched voice. 'I am resolved to be. I'll hold you living, and I'll hold you dead. Come down!'

Riderhood went over into the smooth pit, backward, and Bradley Headstone upon him. [695-696]

The title of the illustration alludes specifically to lines at the opening of the above excerpt, when, despite Headstone's attempts to "shake him off," Riderhood dogs his every step, carrying the bundle of clothes that implicate the schoolmaster in the attempted murder of the attorney months earlier. To the last, Bradley Headstone, despite his pleading minimal income as a schoolmaster, is a gentleman, his dark top coat and respectable bourgeois top hat and ramrod, pillar-like straightness contrasting bareheaded Riderhood's working class clothing and rounded form. The novel's visual conclusion is a suitable match to its opening in "The Bird of Prey", which is also set against the backdrop of the Thames and involves two figures. In the former, Gaffer and Lizzie had been fishing for corpses on the polluted lower river; here, at the pristine, frost-whitened and snow-covered headwaters, the two antagonists are about to drown and become objects of a similar search. But, in destroying the despicable, bullying Riderhood at the cost of his own miserable existence, Headstone retains his gentlemanly status and saves from financial ruin and ignominy the devoted schoolmistress who would marry him; in short, his suicide is purposeful and executes a nemesis upon both himself and his adversary.

Cohen has objected to young Stone's inability in "Eugene's Bedside" to "differentiate the various whites of the patient's face, hands, garments, bed coverings, and hangings" (207), but here Stone is clearly master of the black-and-white medium, distinguishing between the lowering grey sky in subtle strokes of dark infused with the white of the falling snow, which has thinly accumulated on the timbers of the lock-gates and sparsely covers the river-bank, down right and to the left. Justly, then, if one considers this ultimate effort — unaided by Dickens in any respect — one may conclude as Cohen does:

Young Stone, while acting the perfect subordinate, had indeed given the author's book an updated look with his more realistic figures. If Dickens was displeased with Stone or with his published illustrations, he never revealed his dissatisfaction — though it must be admitted that his personal fondness for Stone might have inhibited him. [207]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901.

Last modified 2 August 2011