[The following essay and illustrations, which originally appeared in the 1894 Magazine of Art, has been transcribed by George P. Landow from a copy in the Internet Archive. Landow formatted the text and added links to materials on this site. Click on all images to enlarge them.]

ICKENS, said his great and generous rival, quietly came and took his place modestly at the head of English literature. And in such a manner into the front rank of graphic humorists there one day stepped a youth — a young provincial, unknown in the great City, little known out of it, penniless, and nearly friendless. His talent was little known, for very few had seen his work; but those who had, recognised in it at once that unmistakable quality of excellence which appeals not less to the public than to the artist.

The story of Mr. Phil May's life — there is not much of it to tell, and in appearance at least he is still little more than a youth — is as simple and clearly marked as one of his own designs. He was born in 1864 at Leeds. His father was not in good circumstances; and when the child was twelve years old he was taken from school and put in the way of earning his own living. He had always loved to draw. Paper and pencil were his greatest joy, and battle-scenes his favourite subjects. It is true that these battle-scenes foreshadowed but little of future excellence in figure-drawing, for — granted all the suggestion of action and "go" — they contained little else than smoke, imposing in their great volumes of driving cloud, with bayonets sticking out bravely in every direction. The boy loved all this circumstance of war, and imagined not only figures, but whole regiments of them, behind the great rolling curtain: yet it cannot be denied that the ditticulties of the figure, artistically speaking, were as yet unattacked. So, observing the lad's devotion to art, his father sent him, with curious inconsequence, to an architect's, to learn the art and mystery of scheming plans and drawing elevations. It at once became apparent that it was not by architecture that the buy would build up his fortune and carve his way to fame: and after a couple of weeks he turned his back upon the office in despair, exchanging that reposeful and highly respectable profession for one far more Bohemian in its character and customs. He joined a company of strolling players at a salary of not less than twelve shillings a week, and at once took up a unique position in the company. He had, indeed, newly discovered a strange facility for caricature, the result of great power of observation and penetration into character, combined with a keen sense of humour and a rapidly improving excellence with the pencil. His duties then consisted, secondarily, of playing small parts, such as pages and the like, sometimes rising to inform the principals that their carriages waited without. But primarily he had the making of caricatures of the chief actors of the troupe for display in the shop windows of the towns through which they toured. The practice thus afforded him was invaluable; and of hardly less assistance was the encouragement shown to his budding art by the applause of his companions. But the life he led was a hard one, hard enough to be keenly felt by the boy, who yet had never known what luxury might be, and had enjoyed but little even of the barest comfort, but for four years he persevered, travelling, drawing, and acting. In 1878 his first public appearance in the press was made in the now extinct Yorkshire Gossip; and when he was sixteen years of age he returned to Leeds. Here he left the stage behind him. as he had originally left the architect's, and he devoted his energies to such work as he was lucky enough to find to do. And so far did he succeed in challenging recognition that that very autumn he was employed to design the costumes for the great Leeds pantomime.

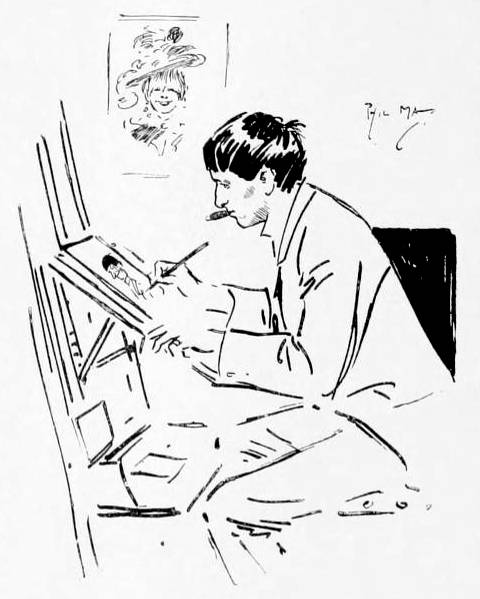

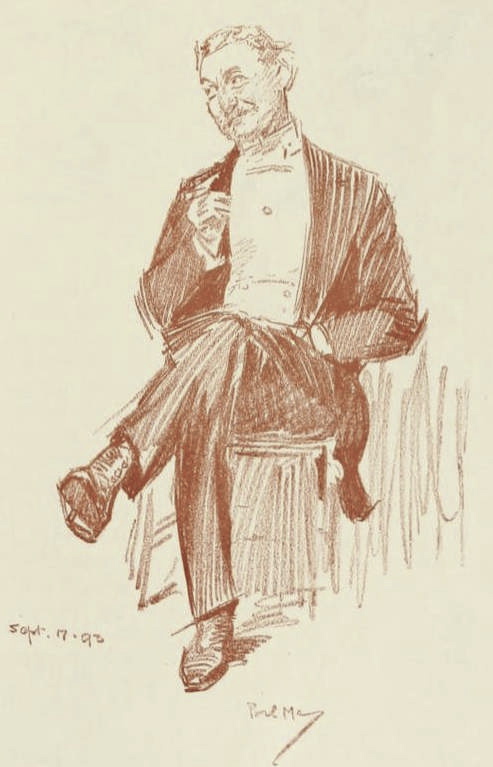

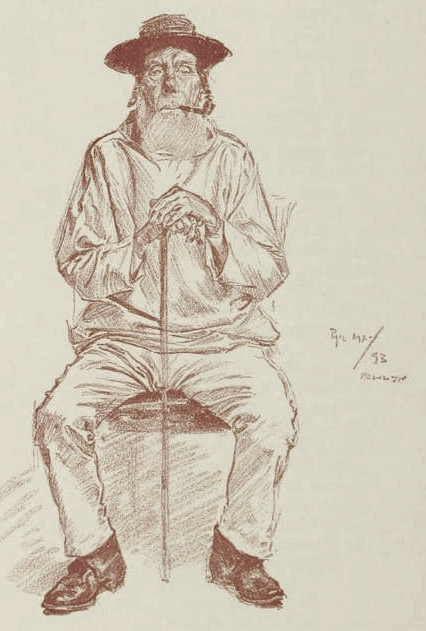

Left to right: (a) Untitled. (b) In Paris. (c) Choosing a Crucifix. (d) At Newlyn. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The same vear — 1882 — Mr. May determined to try his fortune in London town. He came provided with an introduction to Mr. Bancroft's manager, and he quickly proved his powers as a caricaturist by making coloured character-sketches of Mr. Bancroft and one or two other theatrical celebrities for a paper called Society, together with a couple of Christmas number cartoons that were crowded with portraits. For these caricatures he never was paid, but they led to an introduction to the editor of the St. Stephen's Review, for which he began by contributing a sketch of Mr. Toole; and so rapidly did he establish himself as a popular favourite in its pages that within a few weeks he was commissioned to illustrate throughout the Christmas number of that journal, which, under the title of "The Coming Paradise," attracted considerable attention. This work, varied with theatrical costume designing, and occasional drawings for the Penny Illustrated Paper, continued for two years, when Mr. May was tempted to go to Australia to join the staff of the Sydney Bulletin — a paper which its admirers declared to be the funniest paper in the world, a quarry of lunnour worked by the comic papers of other countries in search of fun and originality. It was here that he threw off the trammels of other artists by whose influence he had allowed his genius to be guided, and, by force of circumstances to be recounted later on, adopted that style of draughtsmanship of which he is now the accomplished master.

It is, I believe, generally conceded that those who are minded to "see life," lack neither subject nor opportunity in Australia. Of both Mr. May took full advantage. During 1885 and the three years that followed, circumstances threw him a good deal among "men about town," and to them he devoted as much attention, as much keen analytical study, as his duties (and perhaps his tastes as well) led him to lavish on the theatre, the racecourse, and the prize-ring. He saw all there was to be seen, both in town and in the bush, and then sail for Europe, stopping on his way home to study the Old Masters, and practise oil-painting. In 1889 he came back to England to make drawings for his old paper, the St. Stephen's Review of North's famous ball (Colonel North being a proprietor of the paper); and then he pitched his tent in Paris, whither he went to study art and life — not among the painters' studios, however, nor within the shadow of the École des Beaux-Arts, but in the streets and public places of that kaleidoscopic capital.

On his return to town Mr. May made drawings for the The Graphic, Black and White, the English Illustrated Magazine, Illustrated London News, and the Daily Graphic, as well as for those inimitable "annuals" which, known by his name, have taken the town by storm. It was in 1892, while still an occasional contributor to the Sydney Journal, he produced his "Parson and Painter" (republished from the St. Stephen's Review), which created a veritable furore. Then followed a projected journey round the world via Chicago and San Francisco: and notwithstanding that that journey came to a premature close when the latter city was reached, it was fruitful in sketches, admirable as works of art as they are exquisite as studies of character. Mr. May now divides his time between Paris and London, producing as much as he chooses for the Graphic and the Sketch, and rejoicing, too, at having received his blue ribbon as comic draughtsman at the hands of Mr. Burnand of Punch.

Such, in a few words, are the main facts of Mr. May's artistic life; but that his art may be understood, it is necessary that something should be said on the subject of his artistic temperament. If Mr. May has a fault — and he unquestionably has — it is the excessive generosity of his character. Generous in all things, he is generous most in this, that his admiration is at all times ready to gush forth on the good points of any good work that may come to his notice, and his praises are loud and unselfish to a degree of magnanimity rarely exceeded even by that most magnanimous of all classes — the class of artists. An example I call to mind is when I took him, on his last return to London, into the National Gallery to bring him before the great Fred "Walker — "The Harbour of Refuge" — newly acquired. He gazed at it speechless at first, then smiling and beaming with cheeks and eyes, as he recognised its splendid qualities; and when at last he consented to be drawn away, he muttered "Scorcher." under his breath, and would talk of little else on the way home. Just as frankly appreciative is he of the work of contemporaries, even of so-called rivals. And yet, with all his admiration, he appears to have permitted himself to be influenced by no artist whatever, save at the beginning, while still a lad, by Mr. Linley Sambourne. But even that influence — assumed, no doubt, by that strong feeling for line, or instinct for essentials, which distinguishes both artists — soon wore off, and Mr. May now stands alone in his own line: a man of barely thirty years, without a master, yet with many disciples and more imitators. His power of selection is instinctive and innate. For all that he left school when most boys are still thinking of their games, his taste in literature, as in art, is by nature refined and just, however much his choice of subject, for the sake of his own drawings, may depart from the life of the upper classes; and yet in this refinement, this power of selection, even this method of drawing which he invented for himself, he is always wholly original and powerfully individual.

I have said that Phil May was, to some degree, influenced by Mr. Linley Sambourne, and so, it cannot be doubted, was he also guided by the example of Randolph Caldecott. For not only does he seize the essential lines of a design somewhat in the manner of the latter artist, but his method of suggesting character and humorous expression are in several respects similar to what we find in the best of Caldecott's immortal "toy books." But if Mr. May owes something to Sambourne and Caldecott, it is certain that — contrary to what has been written with some show of authority — he been in no way moved by the example of Vierge, fur the unanswerable reason that until the recent exhibition of Vierge's work was held in London, the young caricaturist had never seen a single example of his pencil.

I say "characteristic:" but in truth it is hardly correct to call him so. There is, indeed, little of that fierce quality of conception about his work, little of that subject-matter which makes you think, little of that sardonic appeal to head and once, which make up the sum of true caricature. "Caricature," says Carlyle, in his essay on Burns, "is drollery, not humour;" and Mr. May is, above all things, a humorist, and neither a politician nor a reformer, nor even if properly understood, a satirist. His aim is to show men and things as they are, seen through a curtain of fun and raillery — not as they might or ought to be. Yet the essence oF his work is truth, inexorable truth; and his version of life is depicted to a grateful public with the unerring pencil of a laughing philosopher. And, moreover, his greatest quality is the astounding excellence of his draughtsmanship; and such excellence, so far from being germane to caricature, is not only unnecessary to it, but sometimes even a hindrance.

Mr. May then, correctly speaking, is a humorist; and not only a humorist in his choice of subject and in his way of seeing things, but emphatically so in the method he employs in setting them before us. His drawing, his very lines, are often funny. As you look in admiration, and sometimes in amazement, at the consummate artistry of this draughtsmanship, you become instinctively aware how genuinely comic are the lines themselves. You can often cover up the heads of his figures, yet find plenty to laugh at in the mere realisation and drawing of their limbs and clothes, the twist of an arm or the cut of a pair of trousers, but in the very lines which compass them round about.

And this is one of the secrets of Mr. May's art. Two leading characteristics, it will readily be seen, distinguish his work: the first, the extreme economy of means by which his effects are produced; and the second, the extraordinary quality of those means — that is to say, of the lines he employs. As regards the former, as I have already hinted, he was originally driven to his present style through foice of circumstances. This consisted in nothing more poetic than the badness, or unsuitableness, of printing-machines. Mr. May had, indeed, always placed due value on the importance of line as against light and shade — seeking rather to suggest chiaroscuro than to express it. But it was the printing-machines of the Sydney Bulletin that lied him to suppress more and more every line that was not absolutely necessary, so that the drawings might be fairly well reproduced hy a rotary printing press, which prints and throws off an issue, at the rate of heaven-knows-how-many copies per hour, on paper little adapted to cine-art purposes.

Pleased with the artistic result of a method which at first was really devised as a self-protection against indifferent fate and callous maehine-minders, Mr. May set about perfecting himself in a method which promised so well both artistically and practically; and he exercised himself with untiring zeal and perseverance until he arrived, presumably, at expressing what he had to express in the minimum of lines.

But it must not be supposed that these sketches — so simply achieved and so free from effort — are obtained with the ease they proclaim. It is the attribute of all great art, this absence of effort in the execution of it. Yet as a matter of fact the "lightning" character of Mr. May's work is as deceptive as Monsieur Renouard's. Mr. May, in spite of appearances, is a slow worker- slow and desperately serious, for all the babbling fun and constant flow of wit and humour that render him and one of the jlliest and most amusing of companions, If he has to introduce into a drawing the portrait of some particular person from whom he is unable to obtain a sitting, he will watch his victim and sketch him with ibe most deliberate care and conscientiousness: he will even "get him in bits" if it is necessary, and, not infrequently, when he returns to his studio the artist will find that he has the nose on one page of his note-book, the eye on another, and the muscles about the mouth on a third; and to obtain a likeness, these must all be pieced together. And then models are procured — for there is little chicin Mr. May's philosophy, for all the appearance of it — and the whole composition is as carefully and accurately worked out as if the design was for a great historical painting, instead of a sketch of just a holiday crowd for the Daily Graphic or a "social cut" for Punch.

And when it is done? "Well, then the artist has before him a finished pencil drawing of consideiable elaboration — a drawing laboriously worked up from life studies, accurate in form, and light and shade: and constructed from studies of landscape or city backgrounds and from figure studies, in chalk and pencil, on paper and in sketch-books innumerable, as well as in the great collection of black chalk on bnown paper, heightened with touches of white, something of the sort we have a score of times admired from Sir Frederic Leighton's hand. Then it is that the artist begins to make his jx'n-drawing, and to eliminate every unnecessary touch, every line that has not its own mission to serve, its own tale to tell. In short, lie pulls down all the elaborate scaffolding by the aid of which he had built up his work, and the drawing stands revealed — complete in its simplicity and simple in its completeness, giving no hint of the labour that evolved it, and extorting from the casual observer the innocent tribute, "Fine, isn't it? Wonderfully good! And evidently, as you see, just knocked off in five minutes!" Five minutes!

It is hard, I am aware, for one who has not seen the method of Mr May's woiking, to realise bow much conscientious labour he lavishes upon his pictures of life and character. In subtlety the best of them are surpassed by few productions of the present day, and may, indeed, be compared with the work of Charles Keene — especially in the masterly ease and certainty in his studies, and the sense of beauty and of feeling revealed in records of landseape and figure alike. A main characteristic, of course, differentiates the younger and cruder master from the elder — his final devotion to line as opposed to "lining," and bis willing sacrifice of effect obtainable by a less heroic method.

In this connection a peculiar practice of primary importance must be mentioned. When Mr. May puts pen to paper and starts upon a line, he continues that line without lifting his hand until he finds himself in danger of going wrong. He thus obtains a continuity of line which to him is of infinite value — combining something of the dignified sweep which distinguished Cruikshank's earliest etchings, and which is one of the chief beauties of Mr. Sambourne's work, with the unerring rightness and instinctive perception which were specially characteristic of Charles Keene's. This it is that gives to Mr. May's portrait-drawings the appearance of facility which makes truth of likeness all the more startling and amusing. Examine the portrait of Mr. Gladstone on the opposite page, a portrait-sketch taken in the House of Connnons, and afterwards redrawn in ink. There is here little trace of caricature, yet it is hard to suppress a smile at the life-like veracity of the sketch. It is as serious as can be; as serious and as successful as Mr. McClure Hamilton's famous painting; and it may be said that fewer truer character-portraits of the unsuspecting sitter have ever been produced. The folded arms are suggested to perfection, not expressed; and the whole pose is as characteristic of Mr. Gladstone, though perhaps a little too robust, as it is admirable from the point of view of art.

A Sketch in the House 1893 [Gladstone]

It is impossible not to recognise that we have here an artist who, far as he has already gone, is destined to go much farther still. Whether he adiieres to his summary method of execution or modities it in the direction of a greater appearance of finish; whether circumstances will induce him to divide his favours more evenly between upper and lower classes; or whether, again, he continues to devote himself more particularly to the humours of the broader side of life — he will find his reputation more and more firmly established in the very front rank of our comic draughtsmen. But, I, for one, believe he will far exceed this point, and that, as Cruikshank did before him, and Robson on the stage, he will extend his field and prove his power as much in tragedy as in comedy; and that, if he is not led away, he will vindicate his position as one of our undoubted masters, whose lure good fortune it is (unlike Charles Keene) to be accepted equally by artists, who appreciate the beauty of his eclectic technique, and by the great public, who, caring little for artistic excellence, hail every new creation of Phil May's with the applause and laughter that are the sincerest tribute to the genuine humorist, the artist, and man of the world.

Bibliography

Spielmann, M. H. “Our Graphic Humorists. Phil May.” Magazine of Art 17 (1894): 348-53. Internet Archive. Web. 13 October 2013.

Created 13 October 2013

Last modified 19 July 2024 (year of publication corrected)