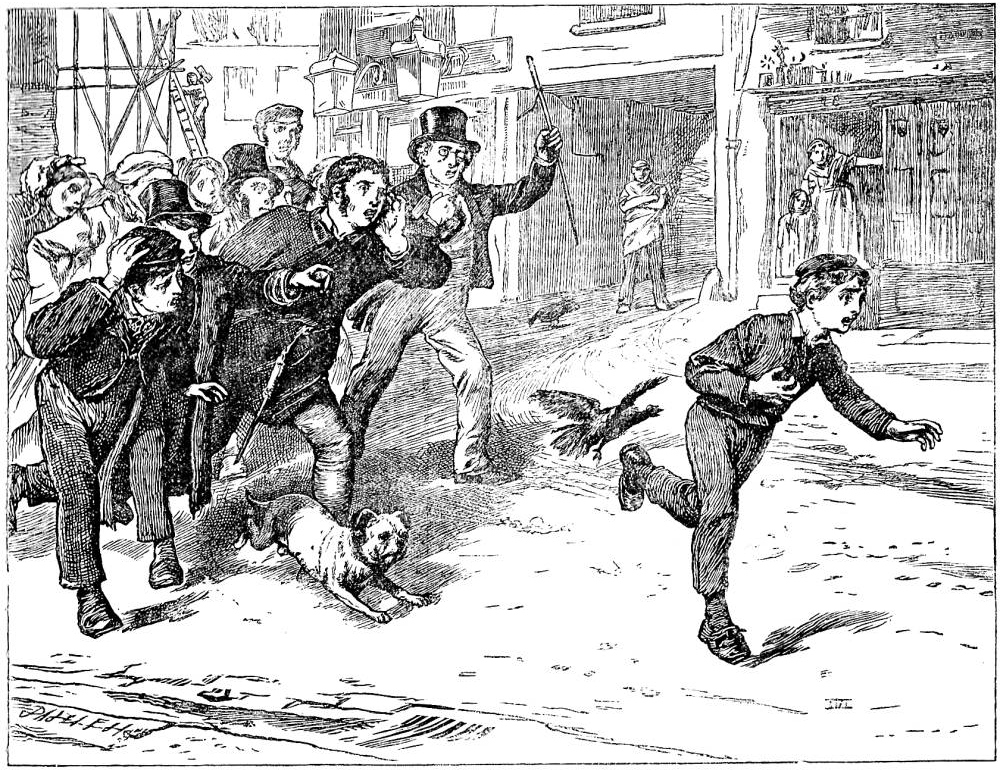

"Stop thief!"," James Mahoney's interpretation of George Cruikshank's pickpocketing scene, in which Jack Dawkins, otherwise known as "The Artful Dodger," and his partner in crime, Charley Bates, steal a gentleman's silk handkerchief in Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Household Edition, page 33. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.1 cm high by 13.8 cm wide. Having run away from his apprenticeship, Oliver has walked seventy miles to London and fallen in with The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates, who have introduced him to the cunning, old fence or receiver of stolen goods, Fagin. To initiate the naive youngster into the ways of the criminal underworld, Fagin has his two best pickpockets take Oliver on a fishing expedition at the bookstalls on "The Green" at Clerkenwell. Seeing the robbery in progress, Oliver takes to his heels, and the victim cries, "Stop thief!" — whereupon the actual thieves, Jack and Charley, take up the cry and lead a mob in pursuit of the hapless Oliver. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

In an instant the whole mystery of the handkerchiefs, and the watches, and the Jewels, and the Jew, rushed upon the boy's mind. He stood, for a moment, with the blood so tingling through all his veins from terror, that he felt as if he were in a burning fire; then, confused and frightened, he took to his heels; and, not knowing what he did, made off as fast as he could lay his feet to the ground.

This was all done in a minute's space. In the very instant when Oliver began to run, the old gentleman, putting his hand to his pocket, and missing his handkerchief, turned sharp round. Seeing the boy scudding away at such a rapid pace, he very naturally concluded him to be the depredator; and, shouting "Stop thief" with all his might, made off after him, book in hand.

But the old gentleman was not the only person who raised the hue-and-cry. he Dodger and Master Bates, unwilling to attract public attention by running down the open street, had merely retired into the very first doorway round the corner. They no sooner heard the cry, and saw Oliver running, than, guessing exactly how the matter stood, they issued forth with great promptitude; and, shouting "Stop thief!" too, joined in the pursuit like good citizens.

Although Oliver had been brought up by philosophers, he was not theoretically acquainted with the beautiful axiom that self-preservation is the first law of nature. If he had been, perhaps he would have been prepared for this. Not being prepared, however, it alarmed him the more; so away he went like the wind, with the old gentleman and the two boys roaring and shouting behind him.

"Stop thief! Stop thief!" There is a magic in the sound. The tradesman leaves his counter, and the carman his waggon; the butcher throws down his tray; the baker his basket; the milkman his pail; the errand-boy his parcels; the school-boy his marbles; the paviour his pick-axe; the child his battledore. Away they run, pell-mell, helter-skelter, slap-dash: tearing, yelling, screaming, knocking down the passengers as they turn the corners, rousing up the dogs, and astonishing the fowls: and streets, squares, and courts, re-echo with the sound.

"Stop thief! Stop thief!" The cry is taken up by a hundred voices, and the crowd accumulate at every turning. [Chapter 10, "Oliver becomes better acquainted with the characters of his new associates; and purchases experience at a high price. Being a short, but very important chapter, in this history," p. 34]

Commentary

In London, Oliver unwittingly joins Fagin's gang of pickpockets, a scene strikingly presented in George Cruikshank's sequence of illustrations for the monthly instalments in Bentley's Miscellany, in the April 1837 steel engraving in Fagin's hideout, Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman. For one brought up in a baby-farm and parish workhouse, Oliver is surprisingly naïve about criminality, so that he has not the slightest notion about the nefarious nature of Fagin's trade, although of course the reader understands completely the nature of the gang's business.

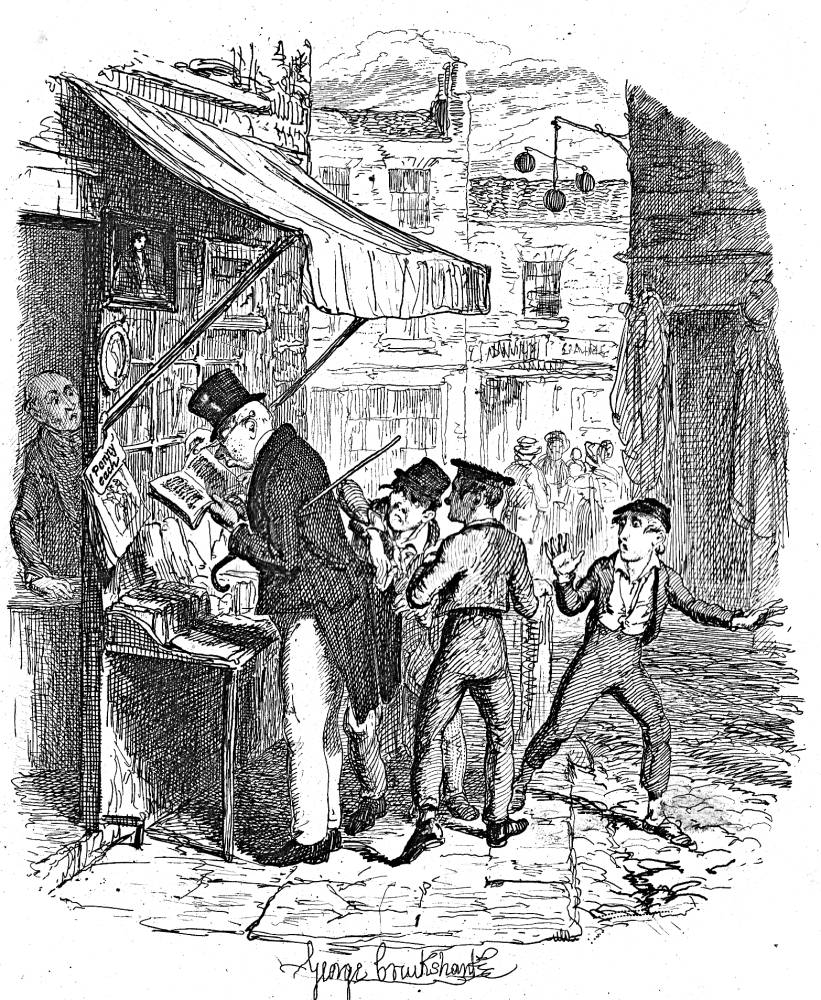

In James Mahoney's sequence, there is no equivalent to the Cruikshank scene in which Oliver first meets Fagin. Instead, in the Household Edition James Mahoney shows not the actual robbery of the book-perusing gentleman, Mr. Brownlow, at The Green, Clerkenwell, which George Cruikshank describes in the rather static May 1837 illustration Oliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work, but the much more dynamic chase scene that ensues when a terrified Oliver runs away from the robbery, drawing attention to himself, and making himself look guilty when in fact he was merely a passive observer.

Although Eytinge has followed his established practice of presenting a pair of closely associated characters in presenting the Artful Dodger with Charley Bates, Furniss realizes not only the fateful meeting of Oliver and Jack Dawkins in the marketplace at Barnet, basing his scene in all likelihood on Mahoney's, but also shows Oliver watching the demonstration in Fagin's hideout in In the thieves' kitchen; Oliver is shown "how it is done", but also the actual theft of Brownlow's silk handkerchief in Oliver's eyes are opened.

Significant as the theft of the handkerchief is in Oliver's descent into the criminal underworld of London, the other illustrators seem to have been reluctant to have their work compared to Cruikshank's, and so reflected upon the incident in different ways: for example, while Eytinge offers a dual character study of the malefactors, Charley Bates and the Dodger, Mahoney depicts the hue and cry after Oliver, in which ironically, both Charley and Jack Dawkins (left foreground) participate. Furniss explores the same scene selected for illustration by Dickens and Cruikshank jointly, but places Oliver, startled, in the background, and develops the dramatic scene in the round, so to speak, foreground the Dodger and Charley, and placing Brownlow with his back to the reader.

In Mahoney's interpretation, Brownlow is approximately centre, the fashionably dressed, middle-aged bourgeois wearing a top-hat and raising his cane. To show Oliver's low status, Mahoney has a dog join the chase and a pigeon fly up behind the boy. An artisan engaged in construction (upper left) pauses to watch the scene, as a man, arms crossed, from the opening of an inn-yard (upper centre) watches, and a woman (right rear) touches her daughter's shoulder protectively as the pursuing mob races past. The picture's focal point is the fleeing Oliver, whose look of terror is complemented by his left hand with which he reaches for his chest — thus, Mahoney suggests the fugitive is already winded and, not knowing where he is going, will soon be apprehended and taken before the magistrate. To direct the reader's eye horizontally, from the last members of the mob to Oliver's outstretched right hand, Mahoney has strategically sketched in the kennel, or central, exposed street gutter common in the high streets of market towns — this juxtaposition of kennel to pursuit suggersts that the viewer, too, is a casual bystander observing the action from the other side of the street. Dressed very much like the fleeing Oliver, Charley hangs onto his cloth cap, but the Dodger (readily identifiable by his rolled-up coat sleeves and battered top-hat) points forward, as if directing Charley towards "the first convenient court" at which they might surreptitiously abandon the chase unnoticed. The "great lubberly fellow" (35) who momentarily will bring Oliver down may be the large man with his hand raised (between the boys and Brownlow), but this figure is not wearing a hat, as in the text. The overall effect, however, is of a powerful complement to Dickens's description of impromptu mob and its atavistic mentality as Mahoney depicts those in pursuit as a largely male juggernaut relentlessly dogging the heels of a single, very frightened little boy.

Illustrations from the Serial (1837), the Diamond Edition (1867), and the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates. Centre: George Cruikshank's original version of Oliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work. Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration (1910) Oliver's eyes are opened. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910.

Last modified 1 December 2014