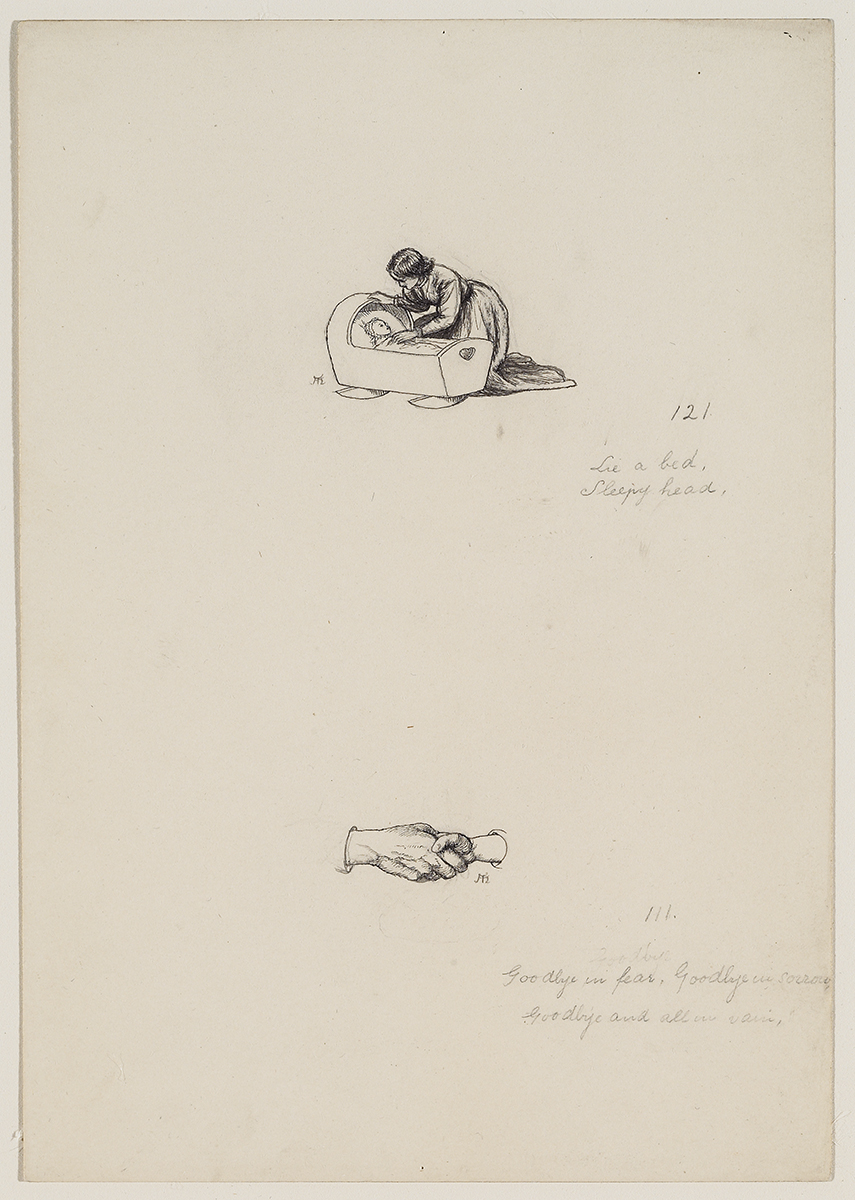

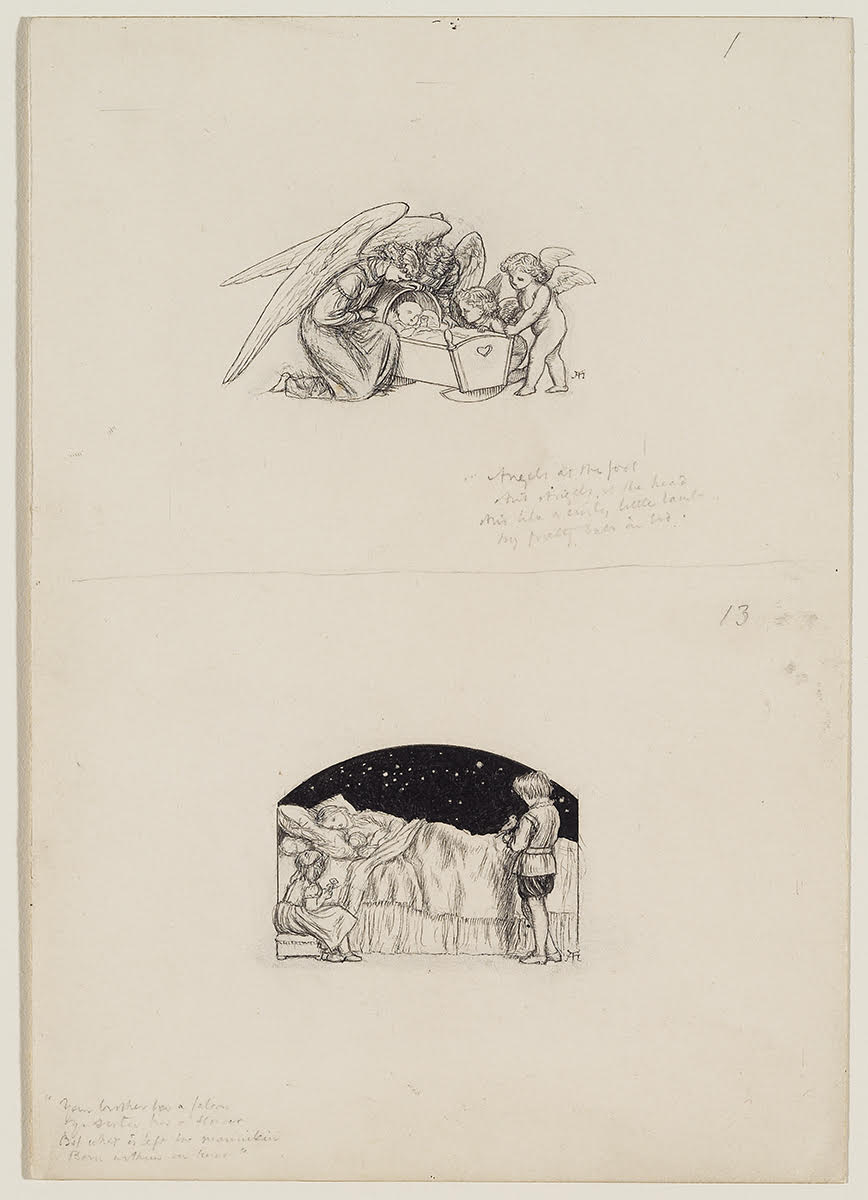

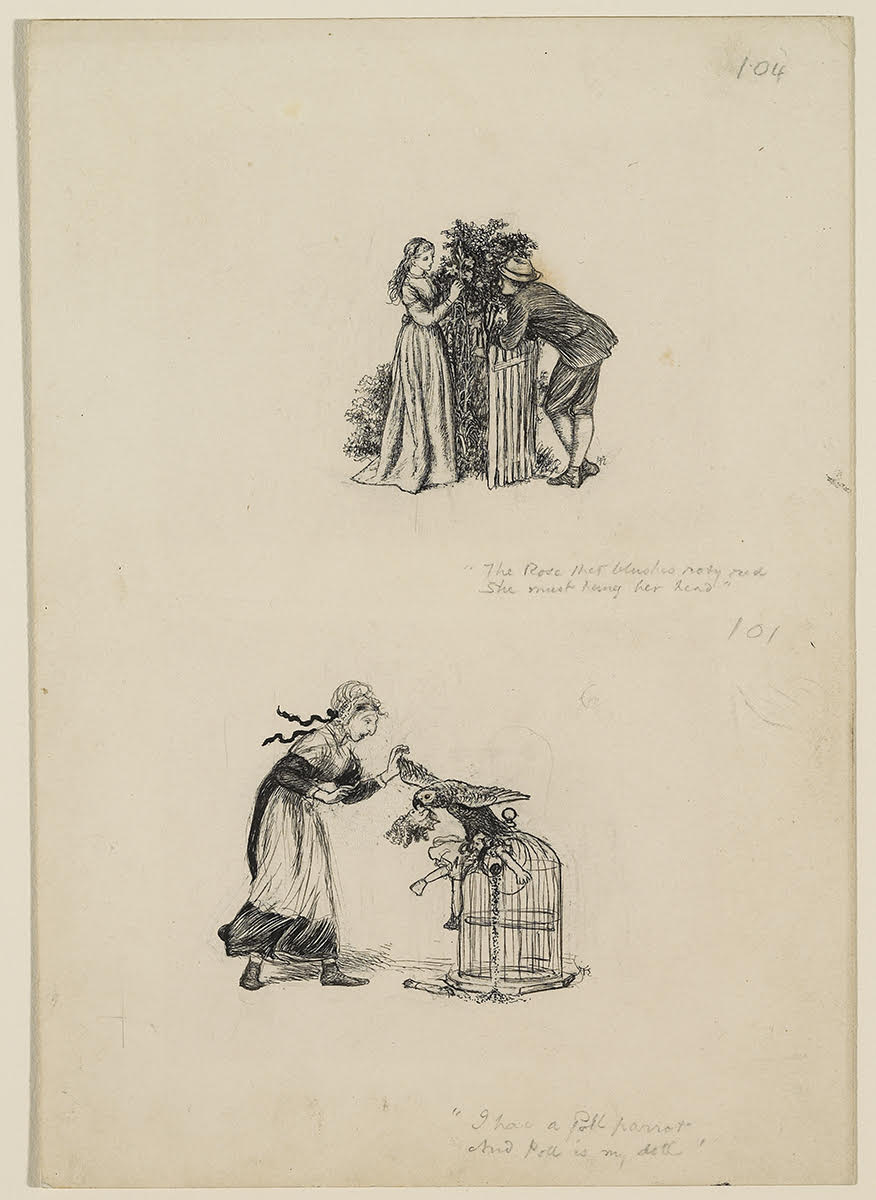

All images after the first come from the collection of the National Gallery of Canada. Dated 1871, they are in pen (and sometimes perhaps brush) and black India ink with graphite on wove paper, measure 10 x 7 inches (25.4 x 17.8 cm), except for the last ("On the grassy banks..." which is very slightly smaller (10 x 6 15/16 inches (25.4 x 17.7 cm)), and are reproduced here by kind permission of the gallery. They are not to be downloaded (the right click has been disabled), but please click on the links under the images to see larger versions of the illustrations as they appear in the book, and the poems that they illustrate. — JB

rthur Hughes's drawings for Sing-Song are amongst his most delightful works for book illustration. Georgina Battiscombe has noted that "never was there a happier partnership between author and illustrator; pictures and poems are welded into an indivisible whole"(142). Unsurprisingly, then, as Stephen Wildman has noted, the designs for these poems "proved, by common consent, to be his most admired and successful illustrations" (27). In view of this it is somewhat surprising to learn the circumstances of how Hughes came to illustrate this book of poems.

Title-page of Sing-Song from the 1915 reprint

in the Internet Archive (public domain).

Christina Rossetti had first approached Macmillan, who had previously published her Goblin Market and Other Poems in 1862, and The Prince's Progress and Other Poems in 1868. They were not particularly interested in this project, however, so she next had discussions with the publisher F.S. Ellis. According to Lorraine Kooistra, Ellis first approached Charles Fairfax Murray about doing the illustrations (57). It has even been claimed that Christina Rossetti had planned to illustrate these poems herself, since her manuscript has sketches in black and red pencil at the top of each verse (see Engen 110). This misconception appears to be based on Dante Gabriel Rossetti's letter of 21 February 1870 to A.C. Swinburne regarding the publisher F.S. Ellis: "My sister is now going to him with a joint edition of her old things (including additions) and also with a book of 101 Nursery Rhymes (illustrated by herself!), which she has lately produced" (D.G. Rossetti, IV, letter 70.31, 376). Although Christina had earlier received some artistic instruction, it seems highly unlikely that she ever seriously contemplated illustrating her own work. In her own letter of 23 February 1870 to the F. S. Ellis she wrote: "Sir, I understand from my brother Mr. Rossetti that you are desirous of seeing some Nursery Rhymes I have just completed, and which I send you by book-post. I shall be very glad if we can come to terms for the publication. I fear you may have misconceived what the illustrations amount to, as they are merely my own scratches and I cannot draw, but I send you the MS just as it stands" (W.M. Rossetti, Diary, 37n.2). Even her other brother William Michael Rossetti, who eventually came to own this original manuscript, would later state: "The vignettes are interesting to people who care about Christina and her work, but of course are highly primitive from an art point of view" (81).

Christina herself wished her friend Alice Boyd to be the illustrator, but the task proved to be beyond her competence: her designs were not considered professional enough to satisfy either D.G. Rossetti or F.S. Ellis (Marsh 414). Ellis had previously published Christina Rossetti's collection of prose tales entitled Commonplace, which suffered from poor sales. Ellis therefore cooled to the idea of publishing another book by her, particularly after he saw Miss Boyd's weak illustrations for it. Christina wrote to Ellis suggesting that if Miss Boyd perhaps made no further large figure designs the illustrations for Sing-Song might still be saved. She then added: "I can readily imagine that if Commonplace proves a total failure, Sing-Song may dwindle to a very serious risk: and therefore I beg you at once, if you deem the step prudent, to put a stop to all further outlay on the rhymes, until you can judge whether my name is marketable" (qtd. in Weintraub 174). Ellis therefore did just that, withdrawing his commitment to publish, and Christina, at least temporarily, found herself without a publisher. On 9 February 1871 W.M. Rossetti wrote in his diary: "Ellis writes to Christina that he gives up the idea of publishing her Nursery Rhymes, because he can't see his way to getting illustrations suitable to his position as connected with the best artists.... It has been a tiresome affair and I think not well managed on Ellis's part" (43). Later, on 19 April 1871, he recorded in his diary: "Brown thinks that he, Gabriel, and two or three others, might club to illustrate Christina's book - each doing three or four designs of a simple kind. I wish this might take effect, but doubt it; the simpler the designs the better, I have always thought and said, for this particular book" (56).

Ultimately Christina successfully approached the publishers Routledge, via the wood engraving firm the Dalziel Brothers, to publish her book. Routledge, in order to focus on its publishing responsibilities, delegated to selection of the artist(s) to illustrate the book to the Dalziels. Later in the same April,Christina wrote to them, with whom she was negotiating for the English edition of her book, that her acceptance of their offer would be conditional on her approval of the artist who was to illustrate the book: "I gladly agree to the terms you propose and will send you a formal note to that effect, if you will first inform me whom you intend employing to design the illustrations and if of course the name pleases me" (Harrison 369). On 4 May 1871, W.M. Rossetti recorded in his diary that the Dalziel Brothers had written to Christina proposing Johann Baptist Zwecker for birds and animals, Thomas Sulman for flowers, and Francis Arthur Fraser for figures. As W.M. Rossetti was unfamiliar with Fraser, he wrote to the Dalziels asking them to show him any previously engraved designs by him (see Diary, p. 60). On May 15, 1871 William Michael recorded in his Diary: "Obtained some specimens of the wood-designs of F.A. Fraser, whom Dalziels propose for illustrating Christina's book. I don't think him, from the evidence of these designs, at all a desirable man. Wrote to Dalziels to say so, and strongly recommended that Hughes should be invited" (61) Rather than multiple artists Christina and William preferred a single artist be chosen in order to ensure an integrated and consistent overall plan for the book.

Soon afterwards, on 18 May 1871, W.M. Rossetti wrote in his diary: "Dalziels acquiesce and apparently with full cordiality, in my proposal that Hughes should be employed as the illustrator of Christina's book: they even say the only illustrator and to this I quite assent" (63). Despite this the Dalziel Brothers appear to have been quite demanding about the output asked of Hughes for his designs. Hughes produced many of his drawings for Sing-Song while living at a cottage on Holmwood Common, Surrey. William advised Christina, who was then convalescing at Folkestone from a serious attack of Graves' disease, to watch for evidence of "speedy execution" in some of the illustrations (Weintraub 177) Hughes subsequently reworked some designs to Christina's satisfaction. On 28 July 1871 she wrote to William Michael: "By the by, one other letter has come for you, but it is only from Dalziel with a second proof of Sing-Song. Mr. Hughes continues charming" (W.M. Rossetti 34) On 1 September 1871 she wrote to William: "What a charming design is the ring of elfs producing the fairy ring - also the apple-tree casting its apples - also the three dancing girls with the angel kissing one - also I like the crow soaked grey stared at by his peers" (W.M. Rossetti 35).

Left: "Lie a bed, / Sleepy head" [image of page] and "Goodbye in fear, Goodbye in sorrow, / Goodbye and all in vain." [image of page]. Accession no. 4375. Right: "Angels at the foot / And angels at the head / And like a curly little lamb / My pretty babe in bed" [image of page] and "Your brother has a falcon / your sister has a flower / But what is left for mannikin, / Born within an hour" [image of page]. Accession no. 4377.

On 10 September 1871 William Michael Rossetti wrote to William Holman Hunt: "There is a book on nursery songs of hers to come out probably in November - Arthur Hughes is illustrating it with some very charming designs, in the right spirit for such semi-childish semi-suggestive work; and I think the book ought to be a decided success" (Selected Leters, 278). On 19 October 1871, W.M. Rossetti recorded in his diary: "Brown called. I showed him the proofs of Christina's Sing Song, with Hughes's illustrations. He was singularly pleased with both; going so far as to say that the poems are about Christina's finest things, and Hughes the first of living book-illustrators (116). On 13 November 1871 William Michael Rossetti recorded in his diary the details of a dinner party at Dante Gabriel's house at Cheyne Walk, attended by Brown's family and Arthur Hughes: "Hughes says that the illustrations of Christina's book took up his whole time for a while. At first he worked terribly leisurely: but after a certain time Dalziels asked him to furnish ten designs per week; he furnished twenty the first time" (126) The book, after many delays, was finally published simultaneously in November 1871 in England by Routledge, and in the United States by Roberts Brothers. Christina was so pleased with Hughes' illustrations that she felt they "deserve to sell the volume" and to acknowledge the collaborative nature of the project she insisted that his name be put in larger print on the title page (Kooistra, 59).

Christina received her advance copy on 18 November 1871, with general publication following two or three days later. She was to receive ten per cent on every copy sold. William Michael felt "it ought to be a great selling success, and even perhaps may be" (W. M. Rossetti, 209). Although sales initially were a little disappointing, by the first four months over a thousand copies were sold in Britain, and eight hundred copies in the United States. The reaction of both family and friends, as well as the critics, was enthusiastic. On 29 November 1871, D. G. Rossetti wrote to Swinburne: "Have you seen my sister's Sing Song? If not I'll send you a copy … Christina's book is I think divinely lovely both in itself and in Arthur Hughes's illustrations which are quite unequalled for sweetness. I shall get some copies & I will send you one" (D. G. Rossetti, V, letter 71.199, 198-99). On November 30, 1871 D.G. Rossetti wrote to Thomas Gordon Hake: "Arthur Hughes who has just illustrated my sister's Sing-Song so exquisitely. By the bye you ought to try and get him for your book. He is a dear old friend of mine and a true poet in painting. There is no man living who would have done my sister's book so divinely well" (D.G. Rossetti V, letter 71.203, 201). On 11 December 1871, W. M. Rossetti noted in his diary that Swinburne, who had received a copy of Sing-Song from Dante Gabriel, was "most enthusiastic about Christina's book" (137). On 29 February 1872, W. M. Rossetti wrote in his diary about a meeting with Mathilde Blind at a dinner party at Brown's: "Mathilde Blind is a very intense admirer of Christina's Sing-Song: had written a notice of it, which she offered to the Academy, but Appleton [Charles Appleton] seemed to think it too fervently expressed, and Colvin wrote an article instead" (170). This article by the critic Sidney Colvin appeared in The Academy on 15 January 1872. Colvin wrote: "The volume written by Miss Rossetti and illustrated by Mr. Hughes, is one of the most exquisite of its class ever seen, in which the poet and artist have continually had parallel felicities of inspiration" (qtd. in the Diary, p.170n.2).

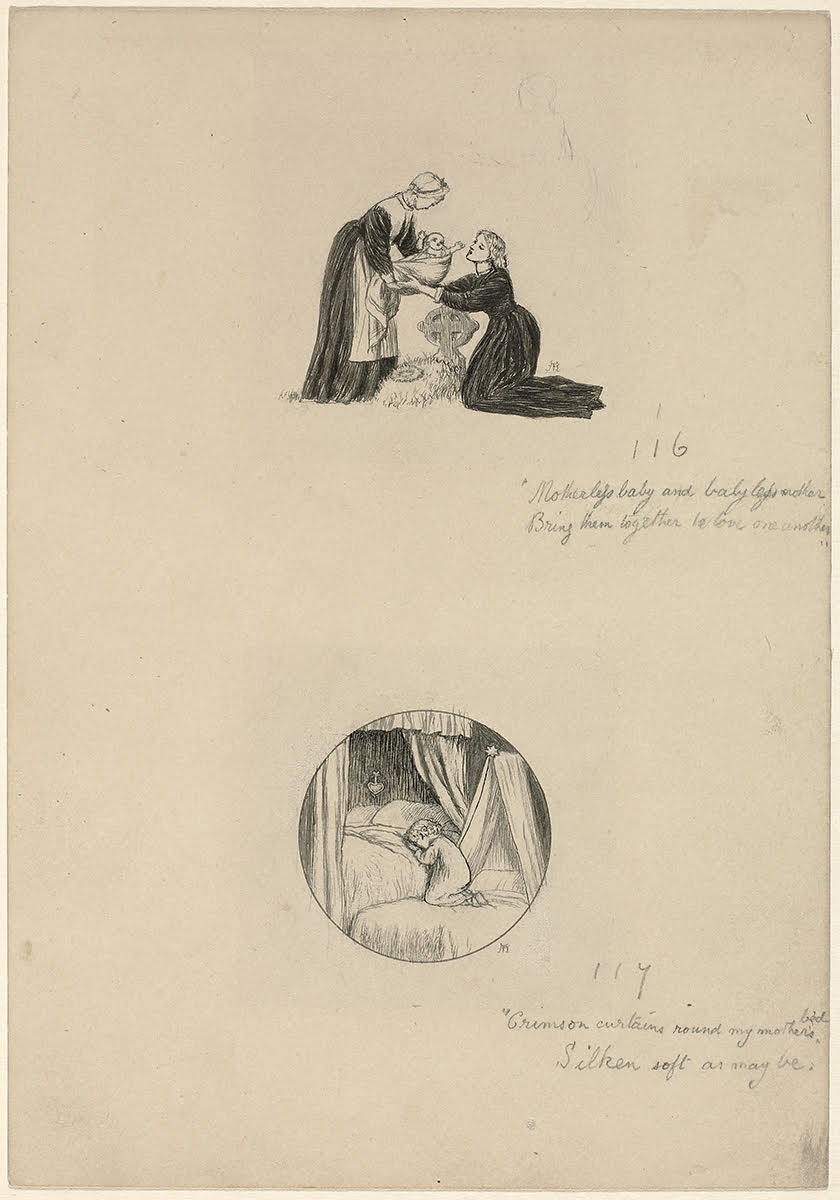

Left: "The Rose that blushes rosy red /She must hang her head." [image of page] and "I have a Poll parrot /And Poll is my doll." [image of page] Accession no. 4379. Right: "Motherless baby and babyless mother - Bring them together to love one another." [image of page] and Crimson curtains round my mother's bed - Silken soft as may be." [image of page]. Accession no. 45429a-b.

Christina was obviously pleased enough with Hughes' work to ask him to illustrate her next book Speaking Likenesses, a fairy-story published in 1874 by Macmillan. On 20 April 1874 she wrote to Alexander Macmillan: "About illustrations: nothing would please me more than Mr. Arthur Hughes... His in my Sing Song were reckoned charming by Gabriel, not to speak of other verdicts" (Packer 100). Christina was once again delighted with Hughes' illustrations, and on November 5, 1874 sent a presentation copy of her book to her brother D.G. Rossetti: "Here is my book at last; and I hope Mr. Hughes will meet with your approval, even if you skip my text." (W.M. Rossetti, 47). Hughes, however, felt his illustrations to Speaking Likenesses were inferior to his for Sing-Song. On 11 January 1895 he wrote to his daughter Agnes Hale-White: "You will have seen in the papers the death of Christina Rossetti ... I have thought for a long time that hers was the most beautiful mind living - indeed I think ever since the old Germ days even. And I like to think I did the Sing Song, and regret dreadfully I did not make better drawings to the Speaking Likenesses" (Roberts, letter 19, 286).

The admiration for Hughes' illustrations for Sing-Song continued well into the 20th century. On 16 January 1911 the illustrator John William North wrote to Harold Hartley, the well-known collector of Victorian wood-block illustrations: "[Hughes'] illustrations to Christina Rossetti's Sing Song, engraved by the Dalziels, are simply the best things of the sort ever done since this world was created - and he would be a wise man in his generation who got together every copy now obtainable" (qtd. in Roberts 268). John Gere has commented that: "Christina Rossetti's book of children's poems Sing Song (1872), for which Hughes made a hundred and twenty-five drawings, [is] outstanding even in that golden period of book illustration" (Ironside and Gere 44). Whalley and Chester have commented about Sing-Song how the "great simplicity in both the words and the accompanying pictures...set a new standard in children's books at a time when the illustration - and indeed the whole page - was becoming cluttered with detail and obsessive colour" (44). Susan Casteras felt that Hughes was an inspired choice to illustrate this book: "As with MacDonald [George MacDonald], this pairing too of author and artist was fortuitous, and, as has been suggested, Hughes' understated yet expressive images match the sweetness, simplicity, and even the occasional morbidity of Christina Rossetti's poems. However, as in other examples, Hughes often injected a note of melancholy or sadness into his designs, heightening these tendencies in the original poem" (31).

Hughes' illustrations to Christina Rossetti's poems are appropriate to the text and seem to focus on the principal idea in each poem. In view of this it is interesting to discover that the elements of the poem he chose to illustrate were not necessarily the same ones chosen by Rossetti herself. Hughes worked directly from Christina Rossetti's own illustrated manuscript because she had hoped that the "scratches" she included "would help to explain my meaning" to the artist chosen to illustrate her poems (Kooistra 58). George and Edward Dalziel, in remembering their collaboration with Rossetti and Hughes on Sing-Song, recalled: "We also published her charming little Nursery Rhyme Book, Sing Song, which was very tastefully illustrated by Arthur Hughes. The manuscript of this book was somewhat of a curiosity in its way. On each page, above the verse, was a slight pencil sketch, drawn by Miss Rossetti, suggesting the subject to illustrate, but of these Mr. Hughes made very little use, and only in two instances actually followed the sketch" (Dalziel Brothers, 91-92). Kooistra argues, however, that George Dalziel's comments have misdirected critics for nearly a century. She re-examined Christina's original manuscript and felt Hughes did use the poet's sketches as the basis for his own designs for many of the illustrations: "A close examination of manuscript and printed text reveals that the artist in fact used the poet's sketches as the basis for his designs, not only for page layout, but also for specific pictorial interpretations: 49 of Hughes's 121 textual illustrations are based directly on the poet's visual guide, and all of them are inspired by her suggestive image/text dialogue" (58-59).

Hughes' drawings for Sing-Song were first drawn in pencil, then in pen and ink, and were subsequently photographically transferred to the woodblock for the engraver to follow. Hughes drew a total of one hundred and twenty small drawings for this book. Of the drawings known to survive for this project thirty-eight are in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, fourteen in the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, eight in the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, seven in the British Museum, London, four in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, two in the Art Museum, Princeton University, and two are in the private collection of Mark Samuels Lasner.

Links to Related Material

- The Memory of Her [Christina Rossetti's] Own Childhood

- The Longing for Motherhood and the Concept of Infertility in the Poetry of Christina Rossetti

- Back to the Nursery and Beyond: A Short History of Nursery Rhymes

- Christina Rossetti's Literary Career

Bibliography

Battiscombe, Georgina: Christina Rossetti. A Divided Life. London Constable, 1981.

Bell, Mackenzie. Christina Rossetti. A Biographical and Critical Study. London: Thomas Burleigh, 1898, 261-270.

Casteras, Susan P. Pocket Cathedrals. Pre-Raphaelite Book Illustration. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1991.

Dalziel, George and Edward Dalziel. The Brothers Dalziel. A Record of Fifty Years' Work in Conjunction with Many of the Most Distinguished Artists of the Period 1840-90. London: Methuen, 1901.

Harrison, Anthony H. Ed. The Collected Letters of Christina Rossetti. Volume I: 1843-1873, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997.

Ironside, Robin and John Gere. Pre-Raphaelite Painters. London: Phaidon, 1948.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen, "The Jael Who Led the Hosts to Victory: Christina Rossetti and Pre-Raphaelite Book-Making." Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies New Series VIII (Spring 1999): 50-68.

Lanigan, Dennis and Douglas Schoenherr. A Dream of the Past. Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Movement Paintings, Watercolours and Drawings from the Lanigan Collection. Toronto: University of Toronto Art Centre and Coach House Press, 2000, cat. 32, 108-12.

Marsh, Jan: Dante Gabriel Rossetti Painter and Poet. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1999.

Packer, Lona Mosk, ed. The Rossetti - Macmillan Letters. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1963.

Roberts, Leonard. Arthur Hughes, His Life & Works. A Catalogue Raisonné. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1997. Cat. no. B36, 264-68.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Chelsea Years II. 1868-70. Edited by William E. Fredeman. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, Vols. IV, 2004.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Chelsea Years III. 1871-1872. Edited by William E. Fredeman. 5 vols. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2005.

Rossetti, W.M. The Diary of W.M. Rossetti 1870-1873. Edited by Odette Bornand. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Rossetti, William Michael. Selected Letters of William Michael Rossetti. Edited by Roger Peattie. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 1990.

Rossetti, William Michael, ed. The Family Letters of Christina Georgina Rossetti. London: Brown Langham, 1908.

Weintraub, Stanley. Four Rossettis. A Victorian Biography. New York: Weybright and Talley, 1977.

Whalley, Joyce Irene and Chester, Teresa Rose: A History of Children's Book Illustrations. London: John Murray Ltd, 1988.

Wildman, Stephen. "Biographical Introduction." In Arthur Hughes, His Life & Works. A Catalogue Raisonné, by Len Roberts. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1997.

Created 22 March 2025