The phrase "nursery rhyme" first appeared in the July 1824 edition of Blackwood's Edinburg Magazine in an essay penned by an anonymous author. Prior to this, the rhymes and songs that are passed from generation to generation in the English-speaking world and remain some of our fondest memories of childhood were known as "songs" or "ditties."

In fact, although evidence clearly shows that recognizable versions of modern nursery rhymes have existed for almost centuries, these remained largely in the oral tradition and surviving written sources only briefly, although tantalizingly, allude to these familiar ditties (Opie 1). For instance, in Shakespeare's King Lear, act three, scene four, the disguised Edgar exits with the lines, "Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man." It seems that the Globe's early seventeenth-century patrons were probably already familiar with this rhyme. Even older is an Anglo-English friar's account, written during the reign of Edward II (1284-1327), of a familiar lullaby:

Lollai, lollai, litil child,

Why wepistou so sore?

Nedis mostou wepe,

Hit was iyarkid (ordained) the yore. [Opie 18]

While other written sources indicate that lullabies and rhymes were used to soothe medieval babies, Iona and Peter Opie point out that most modern nursery rhymes were not originally composed for children, and in fact their original wording would have been wholly unsuitable to young ears never mind their origins as ballads, folk songs, ancient customs and rituals, street cries, or proverbs and subject matter encompassing tavern and mug house practices, war and rebellion, political and religious interests. (4) For instance, the rhyme 'Lavender's blue' can be traced to the opening lines of the seventeenth-century ballad, Diddle, Diddle, Or, The Kind Country Lovers which begins familiarly with the lines "Lavenders green, diddle, diddle, Lavenders blue" but scandalously continues:

You must love me Diddle Diddle

cause I love you,

I heard one say Diddle Diddle

Once I came hither,

That you and I Diddle Diddle

must lie together.

The earliest English publication of nursery rhymes for children appeared in 1744 as Tommy Thumb's Pretty Song Book. Published by Mary Cooper, this volume measured 3 by 1 3/4 inches and included familiar rhymes such as:

Lady Bird, Lady Bird,

Fly away home,

Your house is on fire,

Your children will burn

Sing a Song of Sixpence,

A bag full of Rye,

Four and twenty

Naughty boys,

Bak'd in a Pye.

There was an Old Woman,

Liv'd under a Hill,

And if she 'int gone,

She lives there still.

Mrs. Cooper's volume was quickly followed by other versions of these and other rhymes, most notably S. Crowder and Benjamin Collins' The Famous Tommy Thumb's Little Story Book and The Top Book of All for Little Masters and Misses as well as John Newbery's 1760 Mother Goose's Melody; or Sonnets for the Cradle (Darton 103).

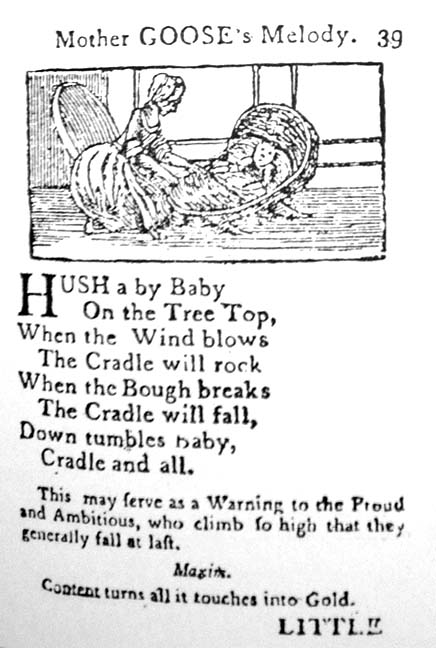

Left: Full page with four rhymes and accompanying moralizations. Middle: "Hush a by Baby." Right: "Little Jack Horner." Bizarre moral statements that seem to have nothing to do with the nursery rhymes accompany them. The moral following "Hush a by Baby," for example, is "This may serve as a Warninng to the Proud and Ambitious, who climb so high that they genreally fall at last. . . . Content turns all it touches into Gold." [Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

Newbery's publication fascinatingly reflects mid-eighteenth century morality; moral observations and lessons accompany much of the rhymes and stories that appear here. For instance,

Hush a bye, baby, on the tree top,

When the wind blows the cradle will rock;

When the bough breaks, the cradle will fall,

Down will come baby, cradle, and all. [39]

is accompanied by the warning, "This may serve as a Warning to the Proud and Ambitious, who climb so high that they may generally fall at last." And to the rhyme,

Three wise Men of Gotham

They went to Sea in a Bowl.

And if the Bowl had been stronger

My Song had been longer. [21]

The publisher adds, "It is long enough. Never lament the Loss of what is not worth having. Boyle."

Finally, although many of the nursery rhymes still sung to infants today pre-date even early modernity, the expansion of children's literature and publications in the nineteenth century imparted important additions to nursery rhyme repertoire. For instance, "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" hails from Jane Taylor's poem "The Star" first published in 1806 alongside a collection of poems entitled, Rhymes for the Nursery.

Bibliography

Anon. Diddle, diddle. Or, The kind country lovers. London: Printed for L. Wright, J. Clark, W. Thackery, and T. Passenger, 1674-1679.

Darton, F. J. Harvey. Children's Books in England. 3rd ed. revised by Brian Alderson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Newbery, John. The Original Mother Goose's Melody. London, 1760.

Opie, Iona and Peter, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951.

Last modified 17 July 2007