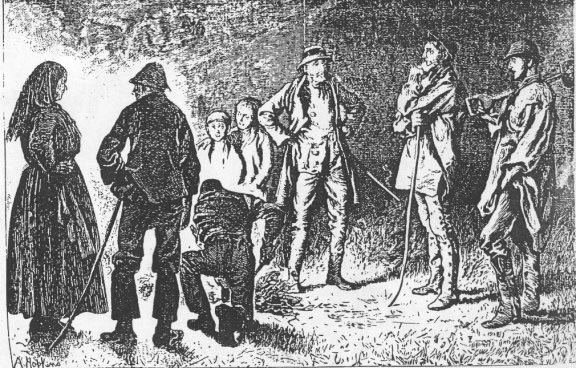

“Didst ever know a man that no woman would marry?” by Arthur Hopkins for Thomas Hardy's The Return of The Native. Plate 1. Belgravia, A Magazine of Fashion and Amusement (January 1878): Vol. XXXIV, to face page 274 (4.3125 inches high by 6.375 inches wide). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Text illustrated from Hardy's The Return of the Native

The speaker, a peat or turf-cutter, who had newly joined the group, carried across his shoulder the singular heart-shaped spade of large dimensions used in that species of labour; and its well-whetted edge gleamed like a silver bow in the beams of the fire. 'A hundred maidens would have had him if he'd asked 'em,' said the wide woman.

'Didst ever know a man, neighbour, that no woman at all would marry?' inquired Humphrey. 'I never did,' said the turf-cutter. 'Nor I,' said another. 'Nor I,' said Grandfer Cantle. 'Well, now, I did once,' said Timothy Fairway, adding more firmness to one of his legs. [Book One, “The Three Women," Chapter III, “The Custom of the Country," 274]

Commentary

The first of Hopkins' twelve illustrations for the monthly serialisation, the Rainbarrow bonfire from the first chapter, “A Face Upon Which Time Makes But Little Impression,” reveals the artist's affinities with the peasant pictures of John Everett Millais, particularly with the elder artist's strong dramatic sense. The opening scene involving the Egdon rustics who constitute the story's chorus shows none of the principal characters. However, some of Hardy's supporting characters are unmistakable: the turf-cutter (identified by his spade over his shoulder), right; Grandfer Cantle, centre; and the "wide woman" (Susan Nunsuch), left. The story's powerful, elemental setting is represented only by the small quantity of furze about to be thrown onto the fire; as is appropriate to the pastoral genre (to which, at this point, Hopkins deemed the novel to belong) the emphasis in the picture is on the Egdon peasantry, whose figures, if not lively, at least express the stolid indifference and stability of those characters as described by Hardy. Jackson points out that one of the most successful features of Hopkins' plates is his "use of light and darkness in an apparent attempt to reflect Hardy's pictorial technique and, quite possibly, to give a sense of the cosmic to the illustrations" (89). Further, as Jackson observes, the rustics as a group appear in six plates, more than any single character, suggesting the importance to the story of the heath society and, by implication, the tragic consequences that result from social alienation. In the first scene and elsewhere in the series, the characters are gathered around the light, symbolic of the communal hearth, and, in a broader sense, the little light of humanity amidst the chaotic darkness of the Darwinian universe."Missing from this scene is the sense of panorama and high visual drama conveyed through the textual description of the Rainbarrow fire leaping into the sky, visible for miles around" (Jackson 93). The focus is not the fire, but the rustics, attuned to the rhythm of the seasons and held together by common traditions such as the November 5th Guy Fawkes bonfire. Their social cohesiveness and solidarity reflect their perfect adjustment to each other, to the man-made forces of convention, and to the natural forces of the heath. Thus, the movement of the novel as Hopkins sees it is away from a cheerful social gathering among the peasantry and towards the dissolution, alienation, and destruction attendant upon the individual's asserting himself over the forces of tradition, convention, and nature.

Related Material

- Henry Macbeth-Raeburn's Frontispiece: Egdon Heath for the Osgoode-McIlvaine Edition (1895)

- Illustrations for the Monthly Serialisation of Thomas Hardy's The Return of the Native

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Hardy, Thomas. Part One: Book One, “The Three Women,” Chapter III, “The Custom of the Country.” The Return of the Native. Illustrated by Arthur Hopkins. January through December 1878. Belgravia, A Magazine of Fashion and Amusement (London), Vol. XXXIV (November 1877-February 1878). Pp. 257-287.

Hardy, Thomas. The Return of the Native. With an etching by H. Macbeth-Raeburn. London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1895.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Towtowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Purdy, Richard Little, and Millgate, Michael, eds. The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy . Oxford: Clarendon, 1978. Vol. 1 (1840-1892).

Vann, J. Don. “Part One. Book 1, Chapters 1-4. January 1878. The Return of the Native in Belgravia, January-December 1878.” Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 84.

Created 5 December 2000

Last updated 10 June 2025