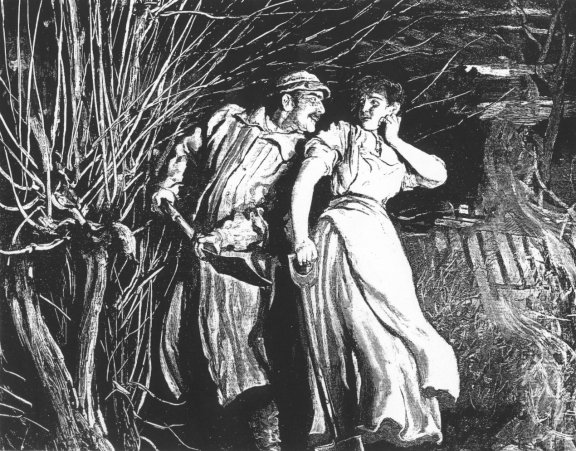

On going up to the fire to throw a pitch of dead weeds upon it, she found that he did the same on the other side. The fire flared up, and she beheld the face of D'Urberville. The unexpectedness of his presence, the grotesqueness of his appearance in a gathered smock-frock such as was now worn only by the most old-fashioned of the labourers, had a ghastly comicality that chilled her as to its bearing. D'Urberville emitted a low, long laugh. by Hubert Von Herkomer. Plate 21 from the monthly serialisation of Thomas Hardy's Tess of the Durbervilles in the London Graphic, 5 December 1891. At 81 words, this is by far the longest title of HH's six plates. Format: double-page (the only other such layout being that of the first illustration, also by Herkomer, this one being the larger of the two) pp. 670-671. Format: whole-page. 33 cm high x 44.7 cm wide (13 ¼ inches high by 17 ½ inches wide). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: A Satanic Presence, Alec D'Urberville Startles Tess at the Fire

Nobody looked at his or her companions. The eyes of all were on the soil as its turned surface was revealed by the fires. Hence as Tess stirred the clods and sang her foolish little songs with scarce now a hope that Clare would ever hear them, she did not for a long time notice the person who worked nearest to her — a man in a long smockfrock who, she found, was forking the same plot as herself, and whom she supposed her father had sent there to advance the work. She became more conscious of him when the direction of his digging brought him closer. Sometimes the smoke divided them; then it swerved, and the two were visible to each other but divided from all the rest.

Detail of the affrighted Tess on the right.

Tess did not speak to her fellow-worker, nor did he speak to her. Nor did she think of him further than to recollect that he had not been there when it was broad daylight, and that she did not know him as any one of the Marlott labourers, which was no wonder, her absences having been so long and frequent of late years. By-and-by he dug so close to her that the fire-beams were reflected as distinctly from the steel prongs of his fork as from her own. On going up to the fire to throw a pitch of dead weeds upon it, she found that he did the same on the other side. The fire flared up, and she beheld the face of d'Urberville.

The unexpectedness of his presence, the grotesqueness of his appearance in a gathered smockfrock, such as was now worn only by the most old-fashioned of the labourers, had a ghastly comicality that chilled her as to its bearing. D'Urberville emitted a low, long laugh.

"If I were inclined to joke, I should say, How much this seems like Paradise!" he remarked whimsically, looking at her with an inclined head.

"What do you say?" she weakly asked.

"A jester might say this is just like Paradise. You are Eve, and I am the old Other One come to tempt you in the disguise of an inferior animal. [Book Fifth, "The Woman Pays," Chapter L, p. 668, bottom of column 1, towards the end of the 21st instalment; in the 1897 edition, Phase the Sixth, "The Convert," p. 668, bottom of column 1: towards the end of the twenty-first instalment).]

Commentary: The Chiaroscuro creates a nightmarish backdrop

The enormous scale of the engraving alone telegraphs to the reader the significance of the almost operatic moment of recognition. Here Herkomer contrasts the emotions of lust and terror, and, in the complementary poses of the poses of the figures, advance and retreat. "Alec's madness and Tess's fear emerge with considerable starkness . . . , and the two figures surrounded by the fires of couch-grass and cabbage-stalks are drawn with a sense of the scene's fine drama" (Jackson 107). Tess's emotional intensity, the leering obsessiveness of Alec and the flames shooting up from the burning debris render Tess's temporary paralysis all the more pathetic. Thus, the scene prepares readers for the heroine's capitulation and loss of self that only his death can counteract.

The extreme chiaroscuro, the rampant, almost melodramatic emotionalism, the swaying of Alec's linen smock-frock and Tess's apron, and the rhythms of the bare thorn tree and undulating smoke to the right are reminiscent of the Roman Baroque of Bernini and Caravaggio. Skeletal branches seem to reach out, as if meaning to snatch the terrified Tess as if they are an extension of the demonic tempter about to seduce the affrighted daughter of Eve, as is wholly appropriate to Alec's allusion to Paradise Lost.

Note: The next illustration in this serialisation is by a different illustrator. For the complete list, see here.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Original Illustrations for Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles Drawn by Daniel A. Wehrschmidt, Ernest Borough-Johnson, and Joseph Sydall for the Graphic (1891)." The Thomas Hardy Year Book, No. 24 (1997): 3-50.

Allingham, Philip V. "Six Original Illustrations for Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles Drawn by Sir Hubert Von Herkomer for the Graphic (1891)." The Thomas Hardy Journal, Vol. X, No. 1 (February 1994): 52-70.

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the D'Urbervilles in the Graphic, 1891, 4 July-26 December, pp. 11-761.

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the D'Urbervilles: A Pure Woman. Vol. I. The Wessex Novels.London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1897.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Vann, J. Don. "Tess of the D'Urbervilles in the Graphic, 4 July — 26 December 1891." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985, pp. 88-89.

Created 14 December 2000

Last modified 15 May 2024