Kate Greenaway, 1870s, albumen cabinet card by Elliott & Fry.

© National Portrait Gallery, London, reproduced with permission

(click to enlarge and for more information).

Kate Greenaway (1846-1901) is best known for pictures of girls in old-fashioned costumes disporting themselves among rural scenes. Yet she was born in Cavendish Square, Hoxton, then in Shoreditch, now a part of the London borough of Hackney. She was the second daughter of John Greenaway, a draughtsman and wood-engraver whose illustrations appeared in the Illustrated London News and Punch. After receiving a big commission to engrave the illustrations for a new set of Dickens, John Greenaway set himself up on his own account, and dispatched his wife Elizabeth and their young family to relatives in Nottinghamshire while he devoted himself to his work. The edition never materialised, and nor did his fee. But the stay in the countryside had an immense influence on the young Kate: "she early developed that taste for childhood and cherry blossoms which became, as it were, her fitting pictorial environment" (Dobson 156).

Greenaway soon showed artistic talent, which her father encouraged. She took evening classes at the Finsbury School of Art, entering it full-time when she was only twelve years old. Her training continued at the women's department of the School of Art in South Kensington, the Heatherley School of Fine Art, and the Slade School at University College, London, where she studied under Alphonse Legros. One of her contemporaries there was Helen Paterson, later Mrs. William Allingham, who much later was to become a close friend. She started exhibiting her work at the Old Dudley Gallery in the Egyptian Hall at Piccadilly in 1868, with a water-colour drawing entitled Kilmeny. Her first exhibit at the Royal Academy was Musing, in 1877. Not long afterwards, her father showed her work to the colour printer Edmund Evans, who decided to take a chance on her. The result, in 1879, was her break-through book, Under the Window, the rhymes for which, as for the later Marigold Garden, 1885, she wrote herself. Under the Window sold 100,000 copies in her own lifetime (Mitchell).

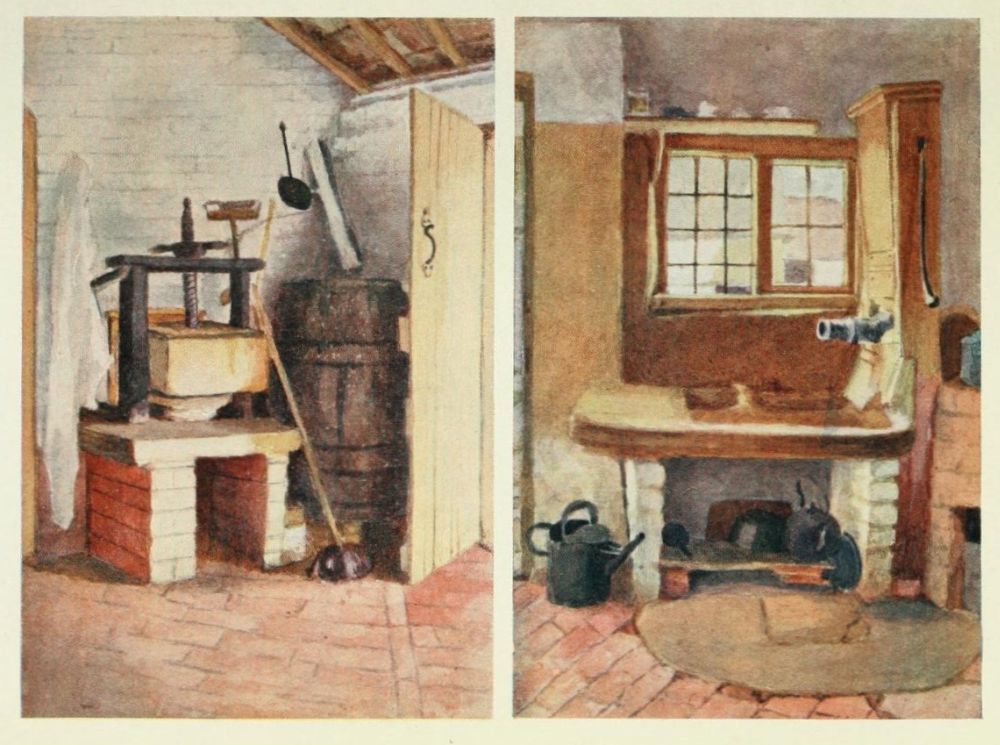

Right to left: (a) John Greenway (Kate Greenaway's father), Wood-Engraver, at Work, by his colleague Birket Foster, 1844. (b) The Kitchen Pump and Old Cheese Press, Rolleston, by Kate Greenaway as a girl. (c) The Bubble, an illustration for William Allingham's poem of the same title in Rhymes for the Young Folk (p.42).

Greenaway's early experiences in Rolleston encouraged her interest in costume, as no doubt did the fact that after returning to London her mother Elizabeth opened a milliner's shop, which broadened its scope to become a ladies' outfitters. Like her mother, Greenaway was good at sewing, and would run up costumes herself, dressing her young models in the kind of clothes that she remembered from her early childhood, or that harked back to the previous century. These dresses and bonnets, with their ribbons and other accessories, first appeared in her valentines and Christmas cards for Marcus Ward & Co, and in magazines like Cassell's Magazine. They proved tremendously influential. For example, in a Times review of an exhibition at the Dudley Gallery, she is mentioned as having been "one of the first to introduce," or rather, reintroduce, the mob-cap (7 March 1879, p. 3), and "with the support of Arthur Lasenby Liberty and his shop in Regent Street the 'Greenaway' look for Victorian girls became all the rage" (Miall 123 -28).

Greenaway's popularity was by no means confined to her home country. Under the Window, for example, sold 70,000 copies at home and the other 30,000 or so in France and Germany (Carpenter and Prichard 226). Americans too enjoyed her work. Indeed, after The Language of Flowers came out in 1884, America proved "a client even better than England" (Spielmann and Layard 127). She had admirers in the art world as well, most famously John Ruskin, with whom she had a long and warm correspondence, and who praised her work in Praeterita and in his Oxford Lectures, where he commented on her "profound sentiment of love for children," and noted the way she put "the child alone on the scene," showing "the infantine nature in all its naïveté, its gaucherie, its touching grace, its shy alarm, its discoveries, ravishments, embarrassments, and victories; the stumblings of it in wintry ways, the enchanted smiles of its spring time, and all the history of its fond heart and guiltless egoism" (145) — though he also encouraged her to lift her art to a higher level, and could be damning too. After seeing The Language of Flowers, for instance, he wrote quite cruelly to her, "You are working at present wholly in vain. There is no joy and very, very little interest in any of these Flower book subjects, and they look as if you had nothing to paint them with but starch and camomile tea" (qted. in Spielmann and Layard 127).

Greenway continued to put out illustrated children's books, from a spelling book to regular almanacks, but was sometimes prevailed upon to illustrate for other authors. Examples of her work had already been found in some of Ruskin's Fors Clavigera (letters to British workmen) of later 1883, not actually as illustrations but as "adventitious decorations" (Spielmann and Layard 119), and then there was an early nineteenth-century rhyming children's story that Ruskin particularly liked, and to which he added some verses of his own, Dame Wiggins of Lee, and Her Seven Wondefrul Cats (1885). Bret Harte's Queen of the Pirate Isle was published with her illustrations in 1887, and Browning's Pied Piper of Hamelin followed in 1889. She became a member of the Institute of Painters in Water Colours in that year too. The Fine Arts Society held three exhibitions of her works during her lifetime, and a fourth soon after her death.

People queuing up on London Open Weekend outside

Greenaway's Hampstead house and studio.

As a young woman, Greenaway was shy, quite unprepossessing and "very much aware of her gracelessness" (Carpenter 226). She was less shy later, but never married, which seems a shame considering her empathy with children and her skill in managing them. Towards the end of her life, she lived at the lovely home in Hampstead which was built for her by the renowned architect Richard Norman Shaw, and which she shared with her parents. She was only fifty-five when she died of breast cancer in 1901, having delayed surgery and kept her suffering mostly to herself (see Engen 214). Her remains were interred at Hampstead cemetery. Perhaps Walter Crane provides the best summing up: "The grace and charm of her children and young girls were quickly recognised, and her treatment of quaint early nineteenth-century costume, prim gardens, and the child-like spirit of her designs in an old-world atmosphere, though touched with conscious modern 'aestheticism,' captivated the public in a remarkable way" (qtd. in Spielmann and Layard 70). — Jacqueline Banerjee.

Note

Follow the link to the Egyptian Hall at Piccadilly to see "Dudley Gallery" written on the left side of the Hall at first floor level

Bibliography

Carpenter, Humphrey, and Mari Prichard. The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. Corrected ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1985. Print.

Dobson, Austin. The Dictionary of National Biography, Second Supplement, Vol. II (Faed - Muybridge). Ed. Sidney Lee. London: Smith, Elder, 1912. 155-56. Internet Archive. Web. 14 May 2013.

Engen, Rodney. Kate Greenaway: A Biography. New York: Schocken, 1981. Print.

Miall, Antony and Peter. The Victorian Nursery Book. London: Spring books, 1990. Print.

Mitchell, Rosemary. "Greenaway, Catherine [Kate] (1846-1901)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 14 May 2013.

Ruskin, John. The Art of England: Lectures Given in Oxford. Orpington, Kent: George Allen, 1883. Internet Archive. Web. 14 May 2013.

Spielmann, M. H., and G. S. Layard. Kate Greenaway. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1905. Internet Archive. Web. 14 May 2013.

The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 May 2013.

-Last modified 18 June 2021