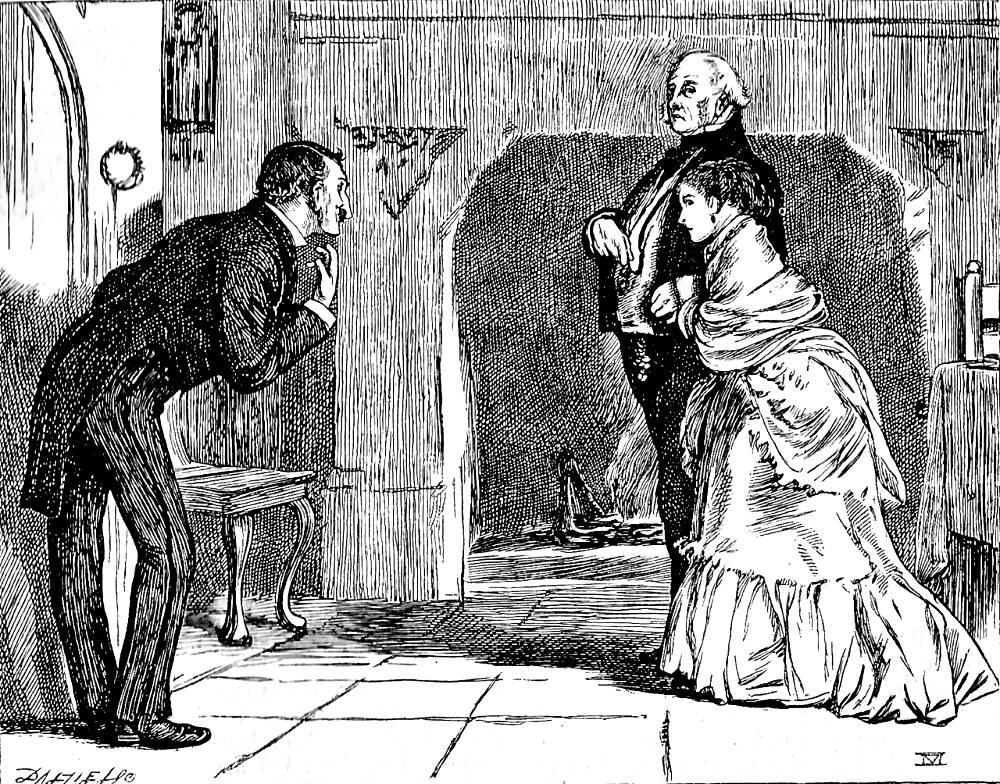

Mr. Dorrit and the Swiss Innkeeper (See page 476.) — Book II, Chapter 3, "On the Road." 9.3 cm by 14.3 cm vignetted, facing XII, 480. Original caption: "You have affronted me," said Mr. Dorrit, in a mighty heat. "How dare you? I tell you, sir, that you separate me from other gentlemen; that you make distinctions between me and other gentlemen of fortune and station." — Dorrit, 476.

Passage Illustrated

These equipages adorned the yard of the hotel at Martigny, on the return of the family from their mountain excursion. Other vehicles were there, much company being on the road, from the patched Italian Vettura — like the body of a swing from an English fair put upon a wooden tray on wheels, and having another wooden tray without wheels put atop of it — to the trim English carriage. But there was another adornment of the hotel which Mr. Dorrit had not bargained for. Two strange travellers embellished one of his rooms.

The Innkeeper, hat in hand in the yard, swore to the courier that he was blighted, that he was desolated, that he was profoundly afflicted, that he was the most miserable and unfortunate of beasts, that he had the head of a wooden pig. He ought never to have made the concession, he said, but the very genteel lady had so passionately prayed him for the accommodation of that room to dine in, only for a little half-hour, that he had been vanquished. The little half-hour was expired, the lady and gentleman were taking their little dessert and half-cup of coffee, the note was paid, the horses were ordered, they would depart immediately; but, owing to an unhappy destiny and the curse of Heaven, they were not yet gone.

"Is it possible, sir," said Mr. Dorrit, reddening excessively, "that you have — ha — had the audacity to place one of my rooms at the disposition of any other person?"

Thousands of pardons! It was the host's profound misfortune to have been overcome by that too genteel lady. He besought Monseigneur not to enrage himself. He threw himself on Monseigneur for clemency. If Monseigneur would have the distinguished goodness to occupy the other salon especially reserved for him, for but five minutes, all would go well.

"No, sir," said Mr. Dorrit. "I will not occupy any salon. I will leave your house without eating or drinking, or setting foot in it.

"How do you dare to act like this? Who am I that you — ha — separate me from other gentlemen?" [Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 3, "On the Road," 475-76: the wording of picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary: William Dorrit Translated into an English Lord

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss's interpretation of the haughty behaviour of William Dorrit emphasizes his sheer bulk. Amy's father, having inherited the wealth to support his conception of himself as a "gentleman," seems to regard himself as an aristocrat superior even to Captain Sparkler's widow, the wife of the English banker Merdle. She, likewise, has an exaggerated sense of her own importance because her husband's wealth she feels, entitles her to pre-empt the Dorrits' reservation at the Alpine inn. She has probably appropriated the Dorrits' rooms by lavishly tipping the grovelling Swiss landlord.

William Dorrit is understandably put out by the innkeeper's giving the banker's wife and her foppish son, Edmund Sparker, preferential treatment at the Great Saint Barnard crossing of the Alps into Italy. His grievance with the partiality shown to the other English travellers is exacerbated by Mrs. Merdle's cutting him socially, after his family's having been made much of by previous publicans on their route from France into Italy. The Dorrits' "great travelling-carriage" (not depicted by Furniss or any of the other illustrators) is reminiscent of that cumbersome vehicle in which Charles Dickens transported his family from London to Genoa in 1844.

Although, as Valerie Browne Lester points out, the Phiz illustrations in Little Dorrit are often superfluous because of the descriptive power of the prose, Hablot Knight Browne's realisation of Mr. Dorrit's continuing arrogance and self-importance marks a significant moment in the novel as The Travellers (see below) is the first illustration in the second book, "Riches." Wealth, as Phiz points out and as Furniss underscores in attempting the same scene, has done nothing to improve either Mr. Dorrit or his daughter Fanny; indeed, their sudden wealth has merely served to magnify their petulance. Only Amy (squeezed in between Fanny and her uncle in the Furniss version) remains untouched by the unexpected windfall that has enabled the formerly indigent Dorrits to undertake an upper-middle-class version of the eighteenth-century the Grand Tour, complete with couriers, servants (suggested by the figures in top-hats in the Furniss illustration), and trains of pack-mules. The corpulent innkeeper bows low before the incensed English traveller with the fur collar and walking stick, obvious manifestations of his "gentlemanly" pretentions, an imperious and portly figure whose gesture is suggestive of contempt for those who have usurped his prerogative and occupied the rooms reserved for his suite. Similarly, James Mahoney's parallel illustration (below) in the Household Edition underscores the silent aloofness of Amy's father as she clings to him for support while Blandois oggles her.

Related Materials: Background, Setting, Theme, and Characterization

- Mr. Merdle's suicide

- Swindlers and Society in Dickens and Carlyle

- Real and Fictional Swindlers: Lever's Davenport Dunn & the Financial Bubble of the Fifties

- Material Culture as Society Informant: Prisons in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit

- Female Saviors in Victorian Literature: Amy Dorrit

- Prisons in Little Dorrit

- Characterization and Setting in Dickens's Little Dorrit

- Dickens's Uses of King Lear in Little Dorrit, David Copperfield, and Other Novels

- Prisons in Victorian England

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Other Illustrations, 1855-1923

- Illustrations by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) (1855-57)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Illustrations by James Mahoney (1873)

- Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1863)

- Illustration by Harold Copping (1923)

Scenes for "Riches" in the original and Household Editions, 1856-73

Above: Phiz's original October 1856 steel-engraving of the middle-class English tourists gathered at the Swiss inn, The Travellers (1857).

Above: Mahoney's introduction of Rigaud (now, "Blandois") among the English travellers at the Swiss inn, As he kissed her hand, with his best manner and his daintiest smile, the young lady drew a little nearer to her father (Book 2, Ch. 1, in the 1873 Household Edition).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

_____. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

_____. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 5 May 2016

Last modified 1 February 2020