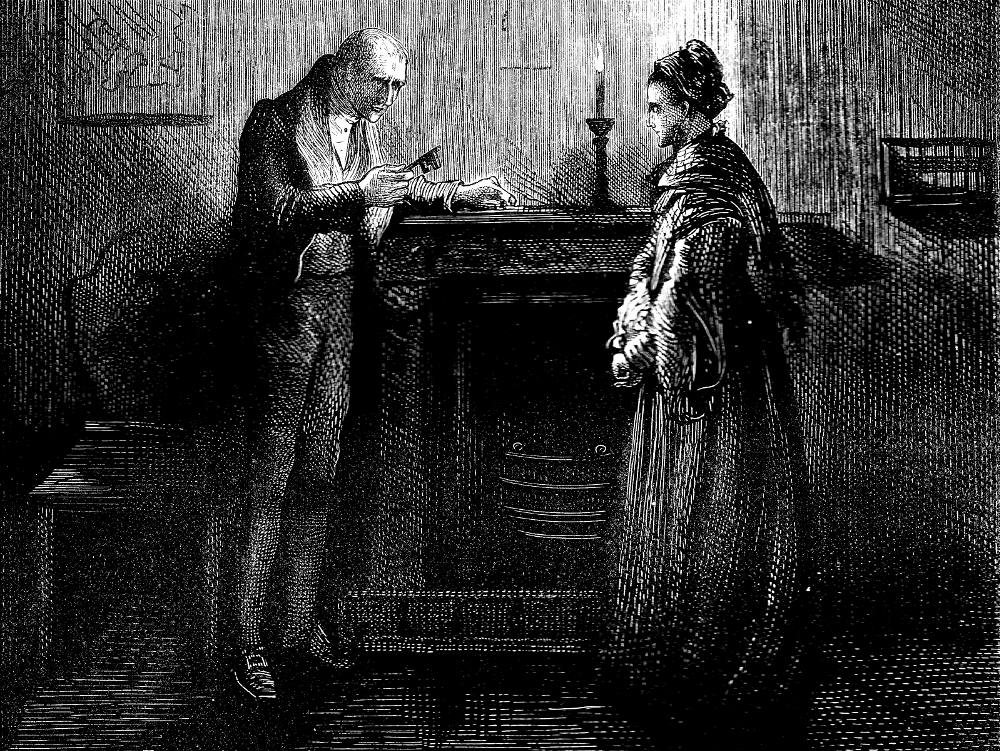

Mademoiselle Hortense

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.4 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 157.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration—> Sol Eytinge, Jr. —> Bleak House —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Mademoiselle Hortense

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.4 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 157.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"Now, mistress," says the lawyer, tapping the key hastily upon the chimney-piece. "If you have anything to say, say it, say it."

"Sir, you have not use me well. You have been mean and shabby."

"Mean and shabby, eh?" returns the lawyer, rubbing his nose with the key.

"Yes. What is it that I tell you? You know you have. You have attrapped me —catched me — to give you information; you have asked me to show you the dress of mine my Lady must have wore that night, you have prayed me to come in it here to meet that boy. Say! Is it not?" Mademoiselle Hortense makes another spring.

"You are a vixen, a vixen!" Mr. Tulkinghorn seems to meditate as he looks distrustfully at her, then he replies, "Well, wench, well. I paid you."

"You paid me!" she repeats with fierce disdain. "Two sovereign! I have not change them, I re-fuse them, I des-pise them, I throw them from me!" Which she literally does, taking them out of her bosom as she speaks and flinging them with such violence on the floor that they jerk up again into the light before they roll away into corners and slowly settle down there after spinning vehemently.

"Now!" says Mademoiselle Hortense, darkening her large eyes again. "You have paid me? Eh, my God, oh yes!"

Mr. Tulkinghorn rubs his head with the key while she entertains herself with a sarcastic laugh.

"You must be rich, my fair friend," he composedly observes, "to throw money about in that way!"

"I am rich," she returns. "I am very rich in hate. I hate my Lady, of all my heart. You know that." [Chapter XLII, "In Mr. Tulkinhorn's Chambers," 333]

My Lady's maid is a Frenchwoman of two and thirty, from somewhere in the southern country about Avignon and Marseilles, a large-eyed brown woman with black hair who would be handsome but for a certain feline mouth and general uncomfortable tightness of face, rendering the jaws too eager and the skull too prominent. There is something indefinably keen and wan about her anatomy, and she has a watchful way of looking out of the corners of her eyes without turning her head which could be pleasantly dispensed with, especially when she is in an ill humour and near knives. Through all the good taste of her dress and little adornments, these objections so express themselves that she seems to go about like a very neat she-wolf imperfectly tamed. Besides being accomplished in all the knowledge appertaining to her post, she is almost an Englishwoman in her acquaintance with the language; consequently, she is in no want of words to shower upon Rosa for having attracted my Lady's attention, and she pours them out with such grim ridicule as she sits at dinner that her companion, the affectionate man, is rather relieved when she arrives at the spoon stage of that performance. [Chapter XII, "On the Watch," 90]

When the Dedlocks return from Paris, they are accompanied a seasoned French maid who is not entirely competent in English; her "Franglais" constitutes her distinctive voice throughout the novel. Mademoiselle Hortense comes from the south of France (either Avignon or Marseilles), and regards herself as superior to English servants. In particular, she takes an aversion to the simple village girl named Rosa whom Lady Dedlock favours. Since she cannot stand to be treated as an inferior in her role as a servant, she despises Lady Dedlock for her haughty manner. She resigns from Lady Dedlock's service when Lady Dedlock replaces her with Rosa, and subsequently seeks to punish her former mistress for her arrogant behaviour. While they are at Chesney Wold, Esther Summerson, Ada Clare, and Mr. Jarndyce watch Mademoiselle Hortense walk through wet grass in bare feet when Lady Dedlock dismisses her from her service. Mr. Jarndyce s uggests that Mademoiselle Hortense is behaving in this peculiar manner so that she will become ill and will possibly die, and thereby punish Lady Dedlock by making her feel guilty. After she leaving Lady Dedlock’s service, Mademoiselle Hortense harasses Mr. Tulkinghorn and Mr. Snagsby, who she thinks may have incriminating evidence about Lady Dedlock’s past. Both these legal figures find her unnerving and regard her as possibly insane. Dickens confirms her emoptionally unbalaced nature at the end of the novel, when she murders Mr. Tulkinghorn for his dismissive attitude towards her; she attempts to exact revenge for Lady Dedlock's real and imagined slights by framing her for the attorney's murder. She confesses her motivation when Detective Bucket apprehends her for the Tulkinghorn murder. Dickens based her neurotic and vindictive character on that of a notorious murderess, Mrs. Marie Manning (1821 – 13 November 1849), a Swiss domestic servant whose public execution (together with that of her co-conspirator, her husband) Dickens attended on 13 November 1849 in London. Dickens wrote to the Editor of The Times later that day:

"Sir — I was a witness of the execution at Horsemonger-lane this morning. I went there with the intention of observing the crowd gathered to behold it, and I had excellent opportunities of doing so, at intervals all through the night, and continuously from daybreak until after the spectacle was over.

"I believe that a sight so inconceivably awful as the wickedness and levity of the immense crowd collected at that execution this morning could be imagined by no man, and could be presented in no heathen land under the sun. The horrors of the gibbet and of the crime which brought the wretched murderers to it, faded in my mind before the atrocious bearing, looks and language, of the assembled spectators. When I came upon the scene at midnight, the shrillness of the cries and howls that were raised from time to time, denoting that they came from a concourse of boys and girls already assembled in the best places, made my blood run cold. As the night went on, screeching, and laughing, and yelling in strong chorus of parodies on Negro melodies, with substitutions of "Mrs. Manning" for "Susannah," and the like, were added to these. When the day dawned, thieves, low prostitutes, ruffians and vagabonds of every kind, flocked on to the ground, with every variety of offensive and foul behaviour. Fightings, faintings, whistlings, imitations of Punch, brutal jokes, tumultuous demonstrations of indecent delight when swooning women were dragged out of the crowd by the police with their dresses disordered, gave a new zest to the general entertainment. When the sun rose brightly — as it did — it gilded thousands upon thousands of upturned faces, so inexpressibly odious in their brutal mirth or callousness, that a man had cause to feel ashamed of the shape he wore, and to shrink from himself, as fashioned in the image of the Devil. When the two miserable creatures who attracted all this ghastly sight about them were turned quivering into the air, there was no more emotion, no more pity, no more thought that two immortal souls had gone to judgment, no more restraint in any of the previous obscenities, than if the name of Christ had never been heard in this world, and there were no belief among men but that they perished like the beasts.

"I am solemnly convinced that nothing that ingenuity could devise to be done in this city, in the same compass of time, could work such ruin as one public execution, and I stand astounded and appalled by the wickedness it exhibits. I do not believe that any community can prosper where such a scene of horror and demoralization as was enacted this morning outside Horsemonger-lane Gaol is presented at the very doors of good citizens, and is passed by, unknown or forgotten."

Left: Fred Barnard's realisation of Hortense's confronting Tulkinghorn: "Turn the key upon her, Mistress." Illustrating with the cellar key — Chap. xliii. Centre: Harry Furniss contrasts the simple, young English maid Rosa and the scheming, vindictive Hortense: The Two Maids (1910). Right: Barnard's description of the English maid, Rosa: "Why, do you know how pretty you are, child?" — Chap. xii (1873).

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1853.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vols. 1-4.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr, and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. VI.

_______. Bleak House, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, volume IV. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XI.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XVIII. Bleak House." The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., [1910], 294-338.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Last modified 15 March 2021