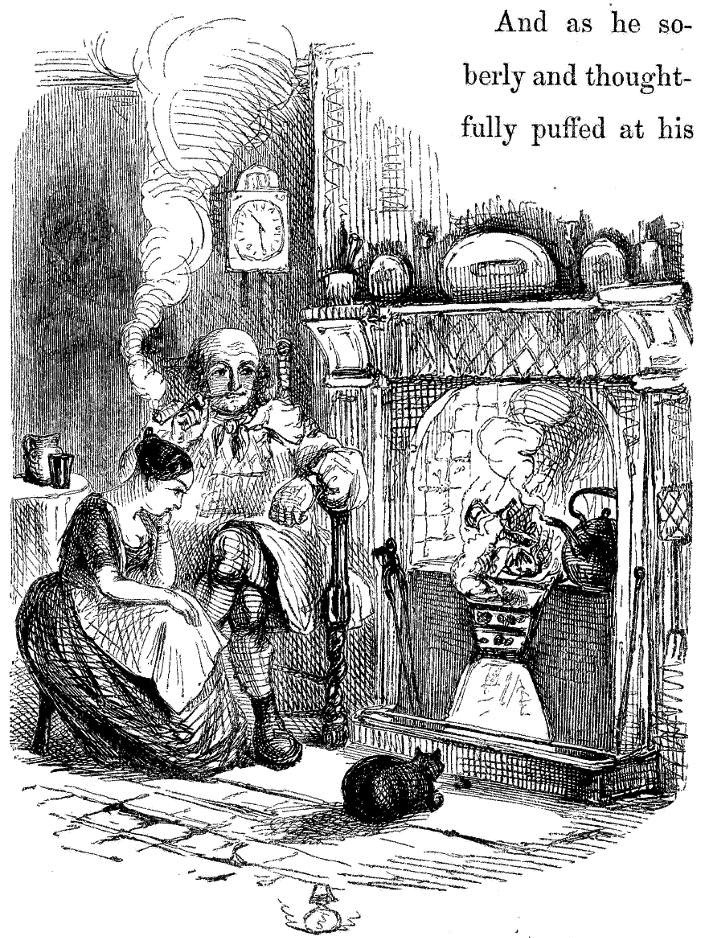

"The Peerybingles," the fourth full-page illustration for the volume by Sol Eytinge, Jr. 7.4 cm high by 9.9 cm wide. The Diamond Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867; rpt., James R. Osgood, 1875). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Realised

Where the baby came from, or how Mrs. Peerybingle got hold of it in that flash of time, I don't know. But a live baby there was, in Mrs. Peerybingle's arms; and a pretty tolerable amount of pride she seemed to have in it, when she was drawn gently to the fire, by a sturdy figure of a man, much taller and much older than herself, who had to stoop a long way down, to kiss her. But she was worth the trouble. Six foot six, with the lumbago, might have done it.

"Oh goodness, John!" said Mrs. P. "What a state you are in with the weather!"

He was something the worse for it, undeniably. The thick mist hung in clots upon his eyelashes like candied thaw; and between the fog and fire together, there were rainbows in his very whiskers.

"Why, you see, Dot," John made answer, slowly, as he unrolled a shawl from about his throat; and warmed his hands; "it — it an't exactly summer weather. So no wonder."

"I wish you wouldn't call me Dot, John. I don't like it," said Mrs. Peerybingle: pouting in a way that clearly showed she did like it, very much.

"Why what else are you?" returned John, looking down upon her with a smile, and giving her waist as light a squeeze as his huge hand and arm could give. "A dot and" — here he glanced at the baby — "a dot and carry — I won't say it, for fear I should spoil it; but I was very near a joke. I don't know as ever I was nearer.

He was often near to something or other very clever, by his own account: this lumbering, slow, honest John; this John so heavy, but so light of spirit; so rough upon the surface, but so gentle at the core; so dull without, so quick within; so stolid, but so good! O Mother Nature, give thy children the true poetry of heart that hid itself in this poor Carrier's breast, — he was but a Carrier, by the way — and we can bear to have them talking prose, and leading lives of prose; and bear to bless thee for their company!

It was pleasant to see Dot, with her little figure, and her baby in her arms: a very doll of a baby: glancing with a coquettish thoughtfulness at the fire, and inclining her delicate little head just enough on one side to let it rest in an odd, half-natural, half-affected, wholly nestling and agreeable manner, on the great rugged figure of the Carrier. It was pleasant to see him, with his tender awkwardness, endeavouring to adapt his rude support to her slight need, and make his burly middle-age a leaning-staff not inappropriate to her blooming youth. It was pleasant to observe how Tilly Slowboy, waiting in the background for the baby, took special cognizance (though in her earliest teens) of this grouping; and stood with her mouth and eyes wide open, and her head thrust forward, taking it in as if it were air. Nor was it less agreeable to observe how John the Carrier, reference being made by Dot to the aforesaid baby, checked his hand when on the point of touching the infant, as if he thought he might crack it; and bending down, surveyed it from a safe distance, with a kind of puzzled pride, such as an amiable mastiff might be supposed to show, if he found himself, one day, the father of a young canary. ["Chirp the First," p. 92-93]

Commentary

In working on the sixteen illustrations that would accompany both Sketches by Boz and The Christmas Books, Ticknor Fields' house illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr., had the difficult task of choosing a single scene that would exemplify The most significant relationships in the romance of distinguise and mistaken motives. Emphasizing the theme of "family values," he decided to focus on the relationship between the middle-aged carrier, John Peerybingle, his young wife, Dot, and their awkward foundling nurse, Tilly Slowboy. The Dickens Index briefly describes the Peerybingles thus:

Peerybingle, John, country carrier, a 'lumbering, slow, honest' fellow and devoted husband of the much younger Mary (called Dot), who is very domesticated but has also a capacity for managing other people's affairs. . . . [Bentley et al., 193-194]

The family grouping, extended to include the sole domestic servant, is not entirely parallel to those of the Cratchits in A Christmas Carol and the Tetterbys in The Haunted Man; rather, in the May-December couple and their infant Dickens presents a somewhat unconventional family paralleling the family groupings of The Chimes (i. e., widower Trotty Veck, grownup daughter Meg, and fianceé Richard) and The Battle of Life (i. e., widower Dr. Jeddler, teenaged daughters Marion and Grace, and quasi-adopted son Alfred). Although only the families in the first and last of the Christmas Books are in any way "typical" of the Victorian middle-class ideal (ironically exemplified by the aristocratic Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their numerous progeny), Eytinge and the other Victorian illustrators appreciated the Vecks, Peerybingles, and Jeddlers as functional and mutually supportive.

This passage depicted or realized by other illustrators:

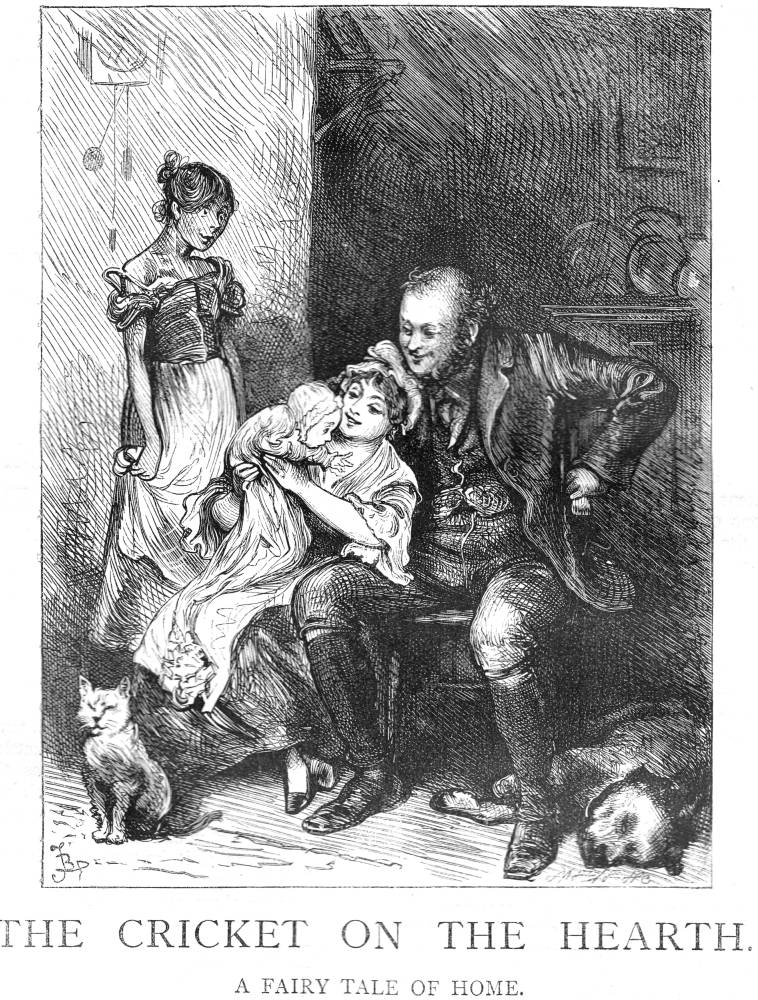

Left: Leech's "John and Dot" one of the original novella's three illustrations describing the Peerybingles' home; centre: Abbey's "Ain't he beautiful, John?" (1876); right: Barnard's "John Peerybingle's Fireside" (1878).

Given the limitations of the Diamond Edition volumes, which contained only sixteen illustrations each, Eytinge could not possibly match in expansiveness the narrative-pictorial programs of the original, individual volumes of the Christmas Books (1843-48), especially since Ticknor and Fields had determined that, in order to make up sufficient pages for the volume, it would have to combine the five seasonal novellas with the collection of periodical observations entitledSketches by Boz — Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Thus, with only eight illustrations to provide for all five Christmas Books, Sol Eytinge was forced to exercise both economy and innovation. Since his second illustration, "Caleb Plummer and Bertha," covers the Cricket's subplot of the missing brother and fianceé, Eytinge required a single illustration that would embrace the entire Peerybingle household, and thereby combine aspects of six of the original novella's plates: Daniel Maclise's "Frontispiece" showing John and Dot before the fire, surrounded by domestic fairies; Richard Doyle's more prosaic "Chirp the First" (showing both the fireside scene and the carrier's covered van); Leech's "John's Arrival" (which introduces Tilly Slowboy as nurse and household factotum); Leech's contemplative "John and Dot", which emphasizes the age disparity between husband and wife by showing John as balding; Edwin Landseer's elegant animal study "Boxer"; and Leech's "Tilly Slowboy", rocking the infant with considerable ungainliness. Moreover, since he was synthesising the work of three illustrators, Eytinge inevitably had to make choices in order to present coherent images of the family members, opting, for example, for a John who, despite his age, is not going bald, but is dressed in a more conventionally middle-class mode (as in Doyle's "Chirp the First") rather than in the carter's linen smock frock of Leech's "John and Dot" and "The Dance." The result is a joyful reunion of husband, wife, and child that includes the orphan Tilly and the family pet; what is missing is the subtle detailing of the hearth, — and John's moral anguish when he incorrectly concludes that his young wife has been unfaithful to him. Eytinge's illustrations study the principal characters (omitting May Fielding, her querulous mother, and the conniving Tackleton) without reveal anything much of the plot.

Eytinge's group character study involves not merely the towering husband and his diminutive wife and child, but also the faithful companion Boxer and the comical, gangly nurse Tilly Slowboy, the subject of pictures by several other nineteenth-century illustrators of the novella, beginning with John Leech's "John's Arrival" and "Tilly Slowboy" (both in the original 1845 Christmas Book), although neither contains the entire extended family as Eytinge presents it. Tilly is dressed in much the same manner in the Leech, Abbey, and Barnard versions of her awkward form, although Abbey in "Tilly Slowboy and the 'Precious Darling'" omits her apron, which is not visible in the last Victorian illustrator's realisation of her in her rocker, Harry Furniss's "Tilly Slowboy," which serves as an interior frontispiece to the novella in the Charles Dickens Library anthology of 1910.

Although in the original novella Clarkson Stanfield in "John and Dot" presents the oddly-matched couple in the ease of their idyllic fireside, the same grouping, more naturalistically presented, does not occur until E. A. Abbey's American Household Edition illustration of 1876, "Ain't he beautiful, John?" and Fred Barnard's 1878 British Household Edition illustration "John Peerybingle's Fireside". In contrast to this perfect domestic harmony, Furniss in his 1910 engraving for the Charles Dickens Library Edition implies some blight or misfortune is about to test the idyllic relationship in "The Shadow on the Hearth."

Given the extreme similarity of Eytinge's Boxer (centre, immediately below the kettle and the fireplace) and the dog as drawn by both John Leech in "John's Arrival" and Edwin Landseer in "Boxer" in the original 1845 Bradbury and Evans edition, it seems quite possible that the American illustrator had seen a copy of the first edition. However, Eytinge's John Peerybingle does not look much like John Leech's, and is costumed as if he were a prosperous farmer. Although it does not contain as much bric-a-brac on the mantelpiece as Leech's in "John and Dot", Eytinge's domestic hearth has the same structure supporting the kettle, and Eytinge has the table laid in exactly the manner of Leech in "John's Arrival." What is interesting about Eytinge's composition is his crowding the figures into the left-hand register, so that the dog, fireplace, and table tend to dominate the centre and right-hand registers. Eytinge's mid-Victorian husband and father is a more rough-and-ready and enthusiastic man of sanguinary spirits in the earlier representations than the philosophical figure presented by Harry Furniss, although the 1910 figure, like Barnard's and Abbey's for the Household Edition volumes, is far better modelled.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Il. John Leech, Richard Doyle, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Rpt., Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Winter, William. "Charles Dickens" and "Sol Eytinge." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 181-207, 317-319.

Last modified 6 May 2013