This is a later, slightly expanded version of a review that first appeared in the Times Literary Supplement of 21 October 2016 (p.35). The author has formatted it for the Victorian Web, adding some extra material, including the illustrations and their captions.

The phenomenal success of George du Maurier's Trilby (1894) made its author uneasy, and served him poorly in the long run. His anti-hero, the hypnotist Svengali, not only manipulated his heroine, but yoked his creator's name to that one sensational title and left him open to the slur of anti-Semitism. It is time to reconsider. Simon Cooke and Paul Goldman's comprehensive and stimulating collection of essays does a fine job of displaying the full range of du Maurier's contributions to late-nineteenth-century culture.

First and foremost, du Maurier was an artist. Turning from painting to illustration after losing the sight of one eye, he became, as Goldman reminds us, a theoretician as well as a prolific and versatile practitioner. He worked in a range of styles from Pre-Raphaelite to melodramatic to comic, illustrating his own and a host of his contemporaries' writing, and spending many years with Punch — the other publication with which he is most closely associated. The essays in Part I enlighten and entertain us by exploring his draughtsmanship, powers of interpretation, and sharp eye for domestic detail and social satire. His illustrations of early sensation fiction, and of works by Gaskell and Hardy, quite rightly earn chapters to themselves. These reveal much about the changing literary scene, the individual texts, and also such incidentals as contemporary fashions and interior design. Considering his work for Hardy's "The Hand of Ethelbert" and "A Laodicean," Philip Allingham admits that du Maurier was most at home in the society drawing-room, and concludes that "Hardy's novels seem to have stretched him in ways he was unable to accommodate" (81); yet the sheer range and precision of what he depicted is still extraordinary.

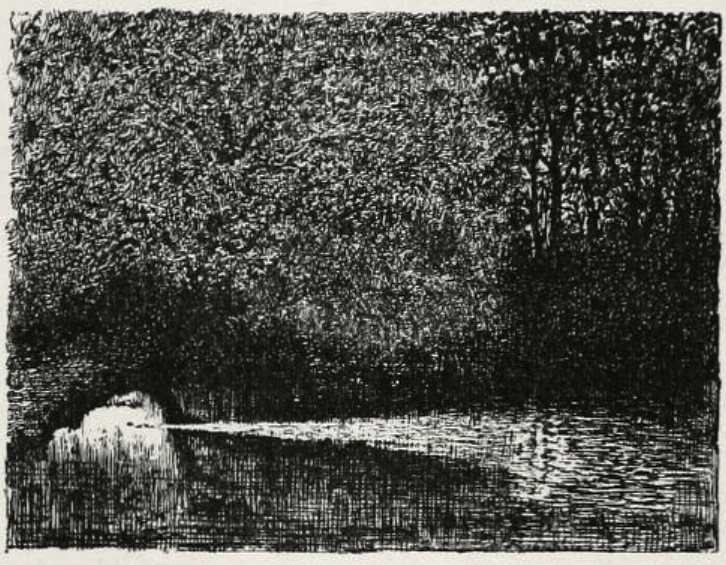

The Old Water-Rat. Source: du Maurier, following p. 213.

Cooke's last essay in Part I, on how du Maurier as author-illustrator projects his own characters' states of mind and enhances their impact, demonstrates an aspect of that range by bringing out the more abstract, experimental and even weird elements of his vision:

Interiority is take to its final extreme in the pictures for Peter Ibbetson. In this novel the images materially enhance the reader/viewer's understanding of Peter's bizarre state of mind.... Indeed, du Maurier deploys his illustrations as a means to trace what is essentially free movement through levels of reality, the past and present, memory and fantasy.... on several occasions we are offered a sort of subliminal image, materializing a mood as much as a perception. The illustrations suggest the innermost point of Peter's consciousness in a series of dream bowers in which the scene is framed by trees and seems to be glimpsed in dim recollection.... [98-99]

The final Goyaesque illustration for this novel of 1891, "The Old Water-Rat," is haunting.

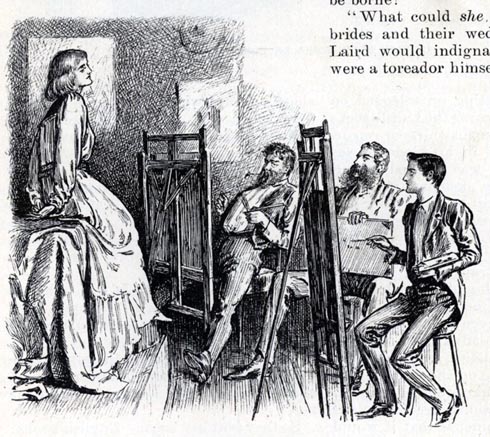

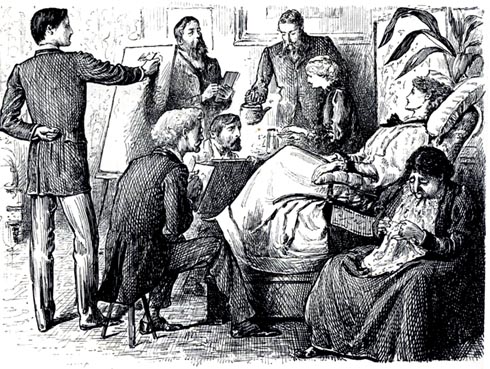

Two of du Maurier's illustration for Trilby (1894). Left: "The Soft Eyes." Right: "A Throne in Bohemia." [Click on these images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

This leads us neatly on to Part II, about the novels, to which du Maurier turned later as his eyesight deteriorated further, and which place him firmly at the fin de siècle. Here we see how variously and appositely he drew on his French background, how well he understood the way men viewed women (the illustrations in Jane Desmarais's piece on Trilby speak volumes) and how thoroughly he engaged with new scientific developments. du Maurier himself thought his last novel, The Martian (1897), his best. It may seem idiosyncratic now, but his extra-terrestrial concerns, and struggle to reconcile the physical with the spiritual, were very much of their time, as was his ultimate faith in human potential. Genie Babb finds correspondences with the works of astronomer Camille Flammarion, H. G. Wells and others, but demonstrates too the individuality of du Maurier's views — something that chimes with Cooke's remarks at the end of Part I, on the uniqueness of du Maurier's detailed reflections on the practice of black-and-white illustrating. Here was an original mind not simply responding to current developments and grappling with the issues, anxieties and hopes of his age, but, as the editors say in their introduction, actively reformulating them (see p. 2).

Part III of this wide-ranging collection looks to integrate all this, dealing with the way du Maurier treats social concerns across the board, with (for example) Leonée Ormond discussing women both in his Punch cartoons, where they are often satirised, and in the novels, where Trilby stands out because of her "energy and natural charm" (194). Sarah Gracombe takes on a harder task, unravelling his and other Victorians' complex feelings, from apprehension to admiration, about Jews:

I argue that Jews serve as figures through which du Maurier articulated a critique, by turns serious and playful, not just of Jewishness but, even more significantly, of Englishness. In particular, du Maurier's representations of Jews reflect at once a Victorian unease with a "Jewish" invasiveness and an admiration for a "Jewish" creativity lacking from the supposedly anemic, anti-artistic sensibility of Englishness itself. [210]

Here again, he was in one sense swimming with the current, but in another sense manipulating it: Gracombe notes "how often du Maurier entwines Jewishness with mockery of English cultural types" (214).

Finally, in an essay by Louise McDonald, film versions of Trilby serve as a coda about du Maurier's "After-life." The most recent version has been the 2013 adaptation Svengali, produced by John Hardwick, which re-imagines Svengali as a Welsh postman turned rockband-impresario. But Cooke and Goldman's collection demonstrates that du Maurier is best remembered not for a single character, however much that character has stuck in the public imagination, but for a whole and highly distinctive body of work. He was a gifted social commentator and illustrator in the late Victorian and fin de siècle years, a particularly fascinating time in English cultural history: these essays, by sixteen of the top specialists in the period, at last allow him to be seen as a key figure in it, in his own right.

Related Material

Bibliography

[Book under review] Cooke, Simon, and Paul Goldman, eds.George du Maurier: Illustrator, Author, Critic: Beyond Svengali. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2016. Hardback. 269 + xviv pp. £66.00. ISBN: 978 1 4724 3159 2.

[Illustration source] du Maurier, George (author and illustrator). Peter Ibbetson. 2 vols. Vol. I. London: J. R. Osgood and McIlvaine & Co., 1892. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Web. 9 January 2017.

Created 8 January 2017