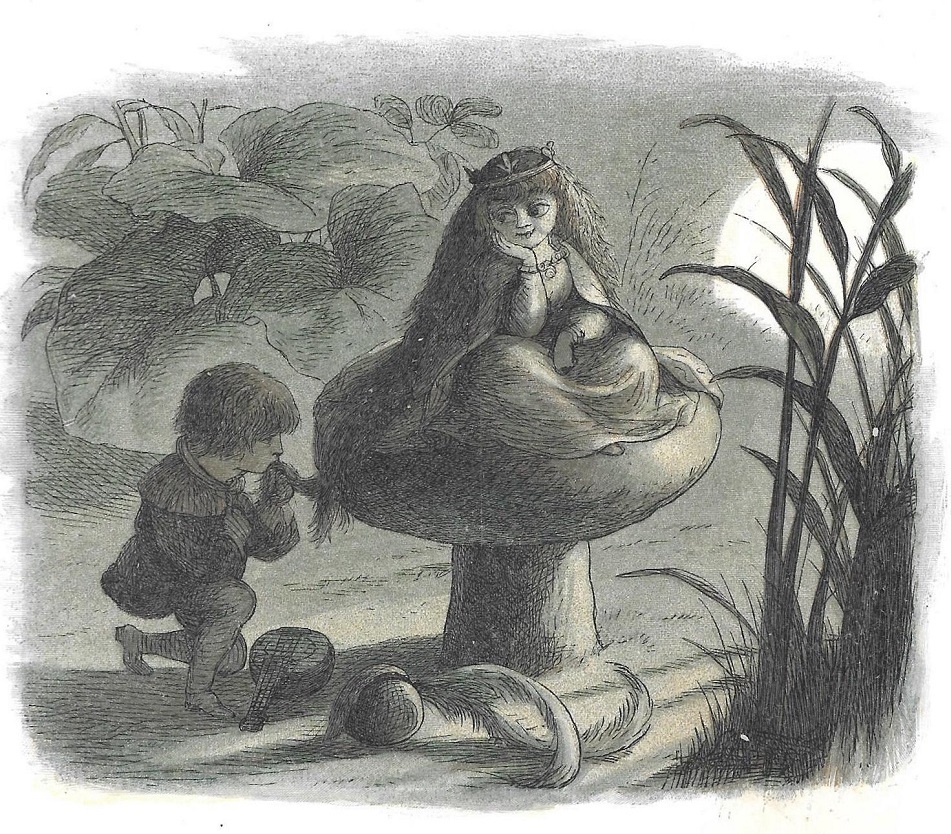

Known, variously, by the nickname 'Dicky' and the pseudonym 'Dick Kitcat', Richard Doyle was one of the most popular illustrators of his time. A natural heir to George Cruikshank, Doyle was a humourist whose work ranged from social satire to representations of fairies and the 'little people'. Characterized by lyricism and lightness of touch, he worked for Punch during the formative years of the 1840s, and later became a sensitive interpreter of Thackeray. His 'elfin' (Muir, 102) masterpiece is In Fairyland (1869-70), a colour-book ostensibly designed for children which also appealed to adults and addressed adult themes in a coded form. Luxuriously produced, with intricate engravings on wood by Edmund Evans, this work set new standards in the field of book-production.

Known, variously, by the nickname 'Dicky' and the pseudonym 'Dick Kitcat', Richard Doyle was one of the most popular illustrators of his time. A natural heir to George Cruikshank, Doyle was a humourist whose work ranged from social satire to representations of fairies and the 'little people'. Characterized by lyricism and lightness of touch, he worked for Punch during the formative years of the 1840s, and later became a sensitive interpreter of Thackeray. His 'elfin' (Muir, 102) masterpiece is In Fairyland (1869-70), a colour-book ostensibly designed for children which also appealed to adults and addressed adult themes in a coded form. Luxuriously produced, with intricate engravings on wood by Edmund Evans, this work set new standards in the field of book-production.

Richard Doyle was born at 17 Cambridge Terrace, London, in September 1824. His father was the Irish cartoonist John Doyle (1783-1851), whose satirical prints were a scourge of the 1820s and thirties. Doyle was one of seven children, and all three of his (surviving) brothers were gifted artists. James (born 1822) was the author and illustrator of Evans's elaborate colour-book, The Chronicle of England (1864); Henry (b.1827) was an illustrator of note; and so was his youngest brother, Charles (born 1842, the father of Arthur Conan Doyle) However, Richard was unquestionably the most able of an exceptional family. Educated at home by his father, Dicky Doyle was a precocious talent.

Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

Aged only sixteen, he published a series of humorous envelopes for the newly-established Post Office, following this up with a satirical comment on Victorian neo-medievalism in the form of The Tournament (1840), a series of cartoons which was also a droll pastiche of the Germanic 'outline style'. In 1843 he joined the staff of Punch and in 1844 designed the intricate front cover, a teeming mass of fairies and elves milling around a rusticated title; revised in 1849, this manic opener established the magazine's emphasis on irreverent mockery, and was used as its signature image until the middle of the twentieth century. Doyle also provided quaint initials, by turns lyrical and surreal, and larger satirical works such as 'The Gold Rush' and 'Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe' (1849). A devout Catholic who valued his Irish ancestry, he left the magazine in 1850 following an attack on Rome.

Five illustrations for John Ruskin's The King of the Golden Rover by Richard Doyle. From left to right: (a)Title Page. (b) Frontispiece (c) Gluck and His Visitor. (d) Gluck revives the young child. (e) Schwartz and Hans drink while Gluck works. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Doyle worked thereafter as a freelance designer illustrating children's books, notably Mark Lemon's The Enchanted Doll (1849)and Ruskin's The King of the Golden River (1851). Other works, this time for adults, included The Foreign Tour of Messrs. Brown, Jones and Robinson (1854) in which he ridiculed the current vogue for tourism by showing a group of Englishmen bumbling their way around Europe, and Thackeray's pastiche of Ivanhoe, Rebecca and Rowena (1850). His collaboration with Thackeray was extended (and tested) in his detailed interpretation of the same author's acerbic novel of manners, The Newcomes (1854-55). This work, his only substantial commission for a contemporary novelist, revisited the blending of fantasy and psychological drama that had earlier characterised his work for Dickens's The Chimes (1845).

Three Lithographs from In Fairyland by Richard Doyle. Fromn left to right: (a) The Fairy Queen Takes an Airy Drive. (b) Triumphal March of the Elf King by Night. (c) Reposing by Night. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

In the sixties his publications divided fairly evenly between fairy books for children (an activity further supported by watercolours) and satirical works such Bird's Eye Views of Society , a series of fold-outs which helped to establish The Cornhill Magazine in 1861-2. His final, most impressive work was In Fairyland (1870, published 1869). Presented as a rich combination of coloured wood-engravings, an accompanying poem by William Allingham and an elaborate binding designed by the artist, In Fairyland was self-consciously designed as a treasure. However, its extravagant price (31 shillings and 6d)ensured that it was far too expensive for all except the most middle-class of households. Two thousand were printed, but records in the Longman Archive (University of Reading, United Kingdom) show that few were sold, a situation which led to the sale of remainders, in the form of a reissue with a revised title-page, in 1875.

In Fairyland's economic failure reflected a change in taste and Doyle subsequently slipped into obscurity. He died of apoplexy (having collapsed on the steps of his club) in 1883, at the unusually young age of fifty nine. Following his death his juvenilia was reissued, principally his Journal of 1840 — a vivid visual record of the life of the times — Homer for The Holidays (1836), and a multi-coloured fantasy, Jack the Giant Killer. Doyle's reputation was eclipsed firstly by the artists of the 1860s and later by the sophisticated urbanities of Beardsley, Ricketts and the artists of the nineties.

Doyle's oeuvre is well-known and his personal life and social milieu are equally well-charted, notably in Daria Hambourg's critical introduction (1948) and Rodney Engen's more extended analysis of 1983. He was a friend of Holman Hunt (Engen, 115-116) and was at home in the company of Millais and Rossetti, Dickens and Cruikshank. His special friend was Thackeray, who, like all of Doyle's associates, made a point of noting his sense of humour and easy charm.

Yet Doyle was also known for his lack of lack of reliability. Characterized by a petulant dilatoriness and lack of focus, he was a poor collaborator. He was consistently late with his illustrations for The Newcomes, only meeting his commitments when Thackeray confronted him with the prospect of the work being passed back into the author's own hand. The Dalziels, who commissioned and engraved several of his works, were similarly frustrated, reporting how An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition (1851) failed to exploit the interest generated by the event because the artist was outrageously slow and unresponsive. Doyle's excuses were often absurd, and the Dalziels reported that on one occasion he failed to meet a deadline because he had 'not got any pencils' (The Brothers Dalziel, 58). Such amateurism hampered the artist's success. Several books did not appear because he lacked the application needed to finish them, and completed work was often uneven in quality, patchily uniting accomplished designs and illustrations that were 'deplorably pedestrian' (Muir, p.102). Dicky Doyle's work is nevertheless a charming combination of comic burlesque, delicate drawing, a magical representation of the fairy world, mythology, satire, and intelligent interpretation. Widely collected, it visualizes mid-Victorian culture at its most wistful and amusing.

References and Works Consulted

Cooke, Simon. 'A Forgotten Illustration by Richard Doyle.'Studies in Illustration , 26 (Spring 2004): 32-34.

Cooke, Simon. 'Notable Books: Richard Doyle's In Fairyland' .The Private Library , Fifth Series, 8:4 (Winter 2005): 153-171.

Engen, Rodney. Richard Doyle .Stroud: The Catalpa Press, 1983.

Hambourg, Daria. Richard Doyle . London: Art & Technics, 1948.

Maas, Jeremy. Victorian Painting . London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1978.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books .London: Batsford, 1971; revised ed., 1985.

The Brothers Dalziel, A Record of Work, 1840-1890 .Foreword by Graham Reynolds. 1901; reprinted London: Batsford, 1978.

Last modified 5 November 2009