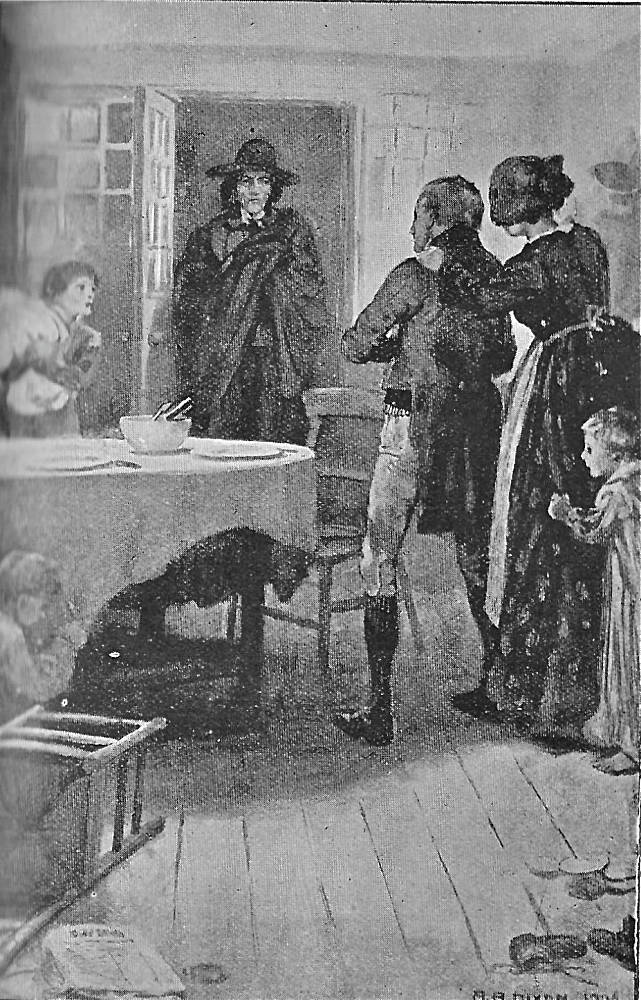

"The good woman ran behind her husband."

A. A. Dixon

1906

Water-colour; lithograph

12.2 cm high x 8.1 cm wide

Seventh and final illustration for The Christmas Books, Collins' Pocket Edition (1906), facing page 416.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

The newspaper in the foreground by the overturned chair reminds us of the dual nature of this space, for beyond the door lies the shop of newspaper vendor Adolphus Tetterby, who stands between his frightened wife (right) and the story's "Haunted Man," the black-cloaked chemistry professor, Redlaw. [Commentary continued below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated from "Chapter II: The Gift Diffused"

The good woman, quite carried away by her honest tenderness and remorse, was weeping with all her heart, when she started up with a scream, and ran behind her husband. Her cry was so terrified, that the children started from their sleep and from their beds, and clung about her. Nor did her gaze belie her voice, as she pointed to a pale man in a black cloak who had come into the room.

"Look at that man! Look there! What does he want?"

"My dear," returned her husband, "I'll ask him if you’ll let me go. What's the matter! How you shake!"

"I saw him in the street, when I was out just now. He looked at me, and stood near me. I am afraid of him."

"Afraid of him! Why?"

"I don't know why — I — stop! husband!" for he was going towards the stranger.

She had one hand pressed upon her forehead, and one upon her breast; and there was a peculiar fluttering all over her, and a hurried unsteady motion of her eyes, as if she had lost something.

"Are you ill, my dear?"

"What is it that is going from me again?" she muttered, in a low voice. "What is this that is going away?"

Then she abruptly answered: "Ill? No, I am quite well," and stood looking vacantly at the floor. ["The Gift Diffused," pp. 426-427]

Commentary

One may well wonder, examining the scene in the Tetterby back-parlour, why Dixon elected not to follow the models in the first edition and Household Edition, and instead showed Redlaw's effect on the news vendor's family. Although showing the "Haunted Man" with the Tetterbys (including Johnny and "Moloch," upper left) has enabled Dixon to introduce both the protagonist and one of the story's principal families at once, the choice of scene precludes visual exploration of the psychological dimensions of the story.

Punch cartoonist and political satirist John Leech in the original scarlet volume published in December 1848 did not present Professor Redlaw and his doppelganger in Redlaw and the Phantom as elegantly as artist John Tenniel in the Frontispiece, without the psychomachia of warring demons and angels framing the morose scientist contemplating his personal misfortunes before the fire, with the ghostly double whispering in his ear. However, the cartoonist's treatment in "Chapter One: The Gift Bestowed" possesses an energy and an inventiveness that the more painterly treatment of Tenniel lacks — in particular, Leech establishes more effectively the academical context of Redlaw's reverie with the books and scientific apparatus that occupy the shelves of the bookcase immediately behind him, and the curtain that separates this intimate, personal space from the lecture theatre in which he practises his profession. Logically, these wood-engravings by Tenniel and Leech should have offered Dixon models for his study of the depressed protagonist — but they did not. Instead, Dixon seems to have taken as his exemplar a moment in which Redlaw's presence contaminates the psyches of others, namely how he affects the usually bustling and optimistic Tetterbys when he arrives to visit their roomer, the poor student who goes by the name Denham.

Thus, John Tenniel's Redlaw on the Landing — Illustrated Double-Page to Chap. II appears to have served as Dixon's model, although there is nothing sinister about the appearance of Redlaw as "pale man in a black cloak," whereas Tenniel's figure on the landing, much larger in scale, casts a baleful shadow as he advances towards the student's room. In fusing the two moments as the text does, Dixon allows the reader to assess the impact of Redlaw's arrival on the Tetterbys, although he does not permit us to see the faces of the parents (right). Curiously, he has dressed Adolphus in the style of the Regency, whereas the original illustrators in such scenes as Johnny and Moloch the little news vendor is clearly wearing clothing in the style of the 1840s, with topcoat and trousers. Whereas in the parlour scene in the original 1848 volume, The Tetterbys the floorboards merely suggest a lack of carpet, in Dixon's illustration the lines of those same floorboards converge with linear perspective at the figure of Redlaw, framed by the doorway, drawing the viewer's eye from open foreground through the figures and table in the middle ground to the disturbing visitor who has just entered.

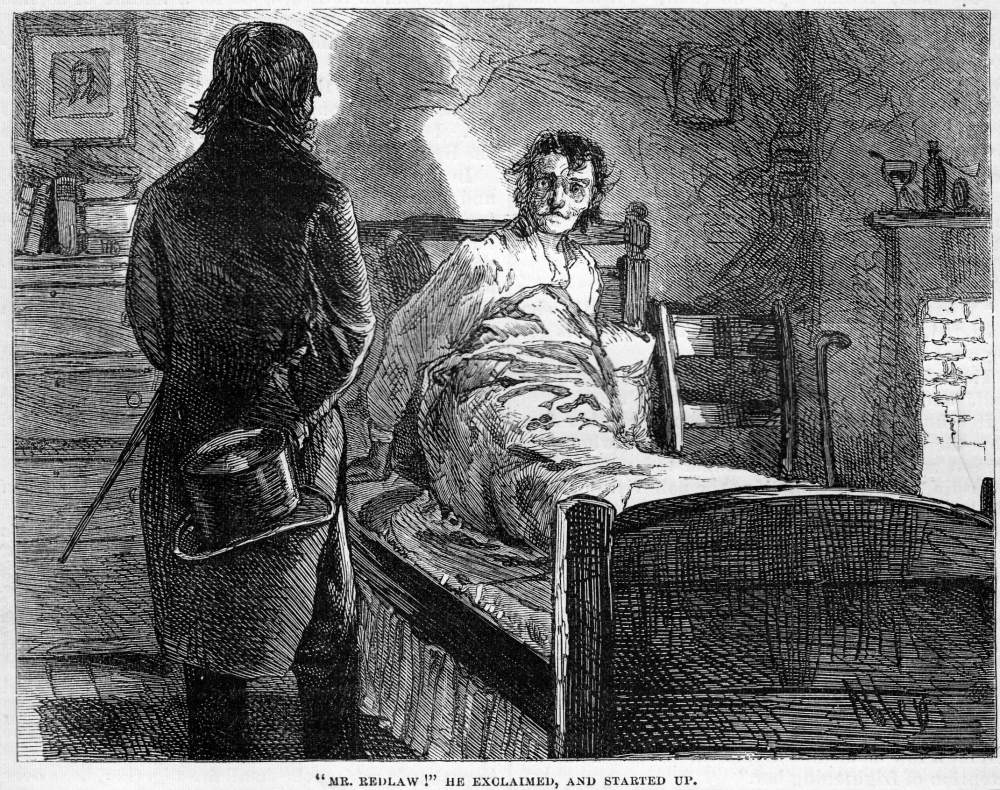

Dixon is not likely to have seen the illustrations of E. A. Abbey in the in the American Household Edition, but he would not have found any of these particularly useful in synthesizing a number of characters from the different plots into one scene, nor was he tempted to deviate from the costume worn by Redlaw in the original, as Abbey has done in 'Mr. Redlaw!' he exclaimed, and started up, in which the visiting professor wears the standard middle-class garb of the late 1840s, a tailored top-coat and beaver hat; however, as if to pique the viewer's interest, Dixon has turned his spectators, Mrs. and Mr. Tetterby, away from the reader, just as Abbey has done with Redlaw, so that readers must construct his expression for themselves. In the British Household Edition, illustrator Fred Barnard has chosen to realize the same moment that Abbey had chosen, but in "Mr. Redlaw!" he exclaimed, and started up Barnard has maintained the original costume specified by Dickens's text and the 1848 illustrations — and rather more effectively engages the reader emotionally by conveying the sense of surprise on Denham's face.

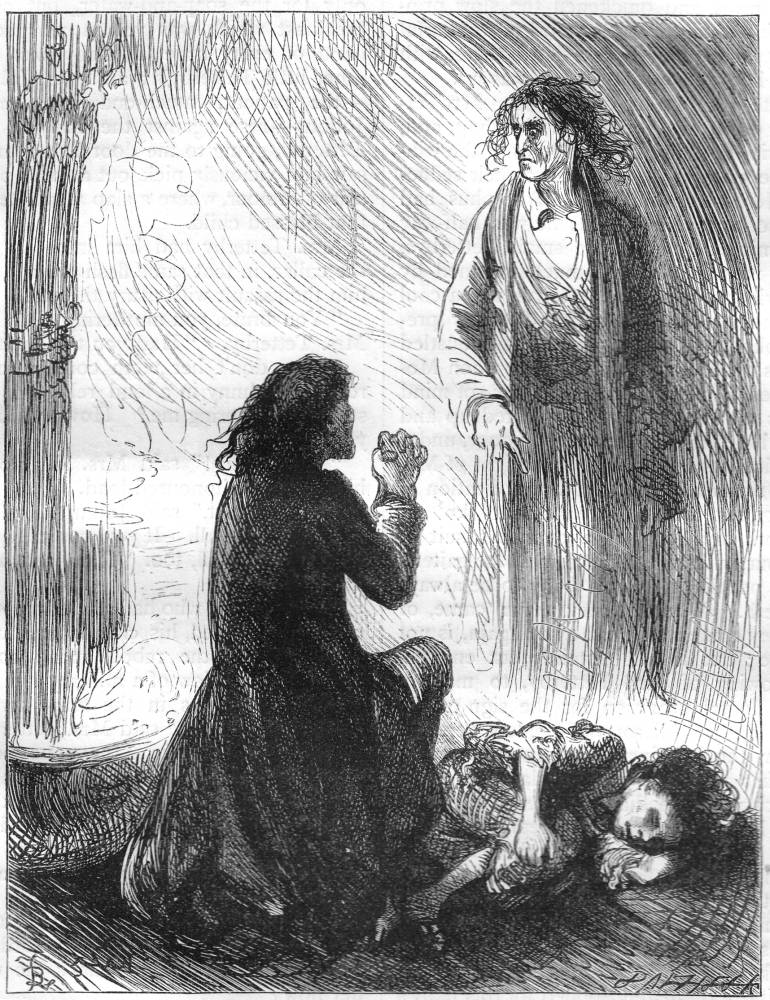

The morose academic and his sardonic double appear by themselves, as in the original novella of 1848, in the sequence of illustrations that Harry Furniss produced four years after Dixon's, as he moves in for a closeup of the pair in The Phantom. The more impressionist early twentieth century pen-and-ink artist has a surer sense of the lower-middle-class Tetterbys in their chaotic back parlour in The Tetterby's Temper, and has included the chagrined Adolphus Tetterby's newspaper screen (rear). Moreover, Furniss presents the baleful influence of Redlaw far more dramatically than Dixon in Spring Killed by Haggard Winter, achieving a psychological effect almost entirely lacking in Dixon's sole illustration for The Haunted Man, much more evocatively illustrated in the single frontispiece for the second volume of the so-called "Household Edition" New York piracy with Felix Octavius Carr Darley's study of the ruminative Redlaw before the fire in As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair. . . (1861), an interesting reconfiguration of the original Leech and Tenniel illustrations that Dixon is not likely to have seen.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions, 1848-1910

Left, John's Leech's "Redlaw and the Phantom and, centre, John Tenniel's "Redlaw on the Landing" (1848). Right: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's "As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire." (1861). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's "Redlaw and The Boy." (1867). Right: E. A. Abbey's "'Mr. Redlaw!' he exclaimed, and started up." (1876). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Fred Barnard's "'You speak to me of what is lying here,' the Phantom interposed." (1878). Right: Harry Furniss's "The Phantom"(1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas-Time. Il. John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Dickens, Charles.The Haunted Man. Christmas Stories. Il. F. O. C. Darley. Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: James G. Gregory, 1861. Vol. 2, 155-300.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 8.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

A. A.

Dixon

Christmas

Books

Next

Last modified 31 March 2014