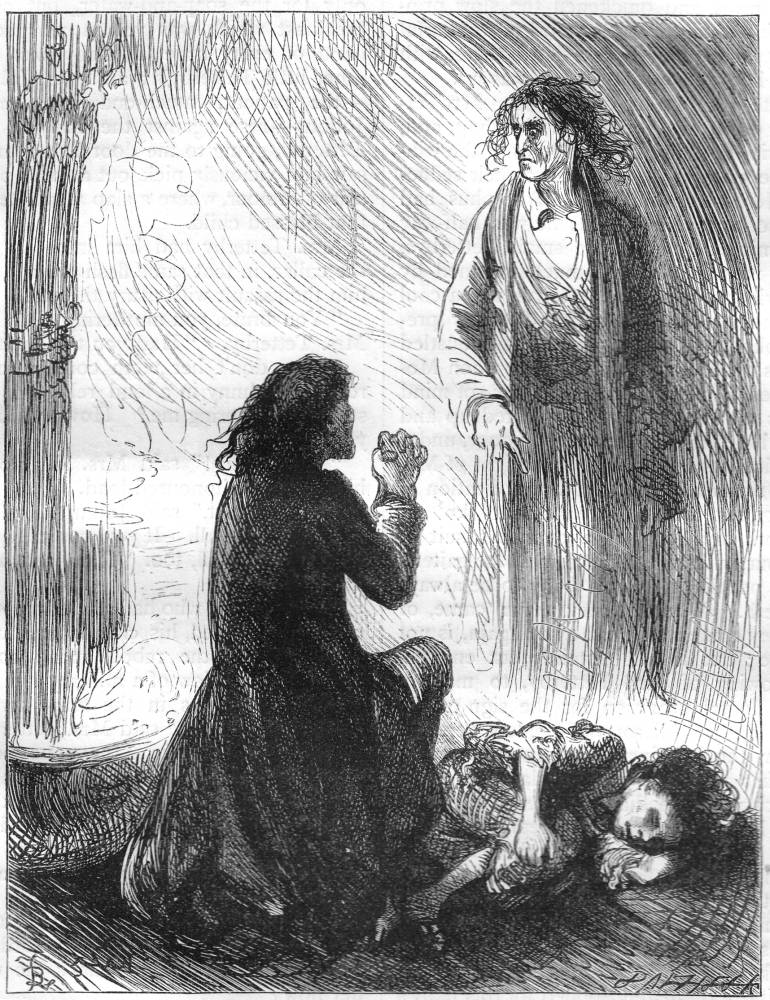

The Phantom

Harry Furniss

1910

14 x 8.9 cm, framed

Dickens's Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing VIII, 325.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Harry Furniss —> Christmas Books —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

The Phantom

Harry Furniss

1910

14 x 8.9 cm, framed

Dickens's Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing VIII, 325.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"I see you in the fire," said the haunted man; "I hear you in music, in the wind, in the dead stillness of the night."

The Phantom moved its head, assenting.

"Why do you come, to haunt me thus?"

"I come as I am called," replied the Ghost.

"No. Unbidden," exclaimed the Chemist.

"Unbidden be it," said the Spectre. "It is enough. I am here."

Hitherto the light of the fire had shone on the two faces — if the dread lineaments behind the chair might be called a face — both addressed towards it, as at first, and neither looking at the other. But, now, the haunted man turned, suddenly, and stared upon the Ghost. The Ghost, as sudden in its motion, passed to before the chair, and stared on him.

The living man, and the animated image of himself dead, might so have looked, the one upon the other. ["Chapter One: The Gift Bestowed," 340]

Furniss's editor, J. A. Hammerton, has selected as a caption for Furniss's study of Professor Redlaw (left) and his doppelganger (right) precisely the same passage that appears opposite John Leech's Redlaw and the Phantom in the 1848 edition. However, Furniss has increased the scale of the figures and decreased the distance between them, thereby eliminating most of the background details pertaining to the chemist's study. And Furniss's university lecturer is fuller faced and older than Leech's, presenting a less romantic and anguished profile as he stares into the flames.

The two original illustrations of this moment in the 1848 edition of the novella — John Tenniel's wreathed image of Redlaw and the Phantom in the Frontispiece and Leech's first contribution, a full-page vignette on page 34 that presents the Doppelganger scene in Redlaw's study (see below), invest the double with supernatural force. E. A. Abbey in the Harper and Brothers American Household Edition presents no such other-worldly visitation, but Fred Barnard in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition volume of 1878 does present graphically Redlaw's second dramatic confrontation with the hovering spirit in "Chapter 3: The Gift Reversed," "You speak to me of what is lying here," the Phantom interposed. Whereas Tenniel's Redlaw merely possesses a receding hairline, Furniss's exhibits an advancing baldness, thereby accentuating his forehead and imparting to him an philosophical aspect appropriate to Dickens's only intellectual character. The composition might be termed a "dark plate" in imitation of the engravings of Phiz in Bleak House since only the faces of Redlaw and the Phantom are lit.

A detailed comparative analysis of Furniss's composition and those of the original illustrators reveals that he has not merely moved the figures into closer proximity; he has also changed their elevation by having the Phantom sitting rather than standing, as in Tenniel's and Leech's versions. The fireplace he merely implies, whereas both Tenniel and Leech include it in the left register, so that the reader in the Furniss text focuses more intently upon Redlaw, whose face is somewhat obscured in the Tenniel frontispiece, in which the Phantom is very much a shade or pale reflection of Redlaw. in contrast, Furniss presents both figures as modelled and solid, as if the Phantom is Redlaw's twin rather than his ghostly double.

Like modern directors' presentations of the Ghost of Banquo in Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Macbeth, nineteenth- and twentieth-century illustrators have had to decide whether to present the doppelganger at all, and, if they do so, whether the presence is primarily supernatural or psychological. Furniss has elected to pursue the psychological interpretation, making manifest Professor Redlaw's deep depression or discontent with his life in the opening illustration, which serves as a frontispiece. The disconsolate chemist appears to be looking for an answer in the pictures in the fire, which fails to illuminate his study, which remains in deep shadow suggestive of his mental state. Whereas the original series of illustrations presented both the psychomachia of warring angels and demons in the wreath surrounding Redlaw and his double in the Tenniel frontispiece and the significance of fairy tales and other wondrous tales of childhood to the cultivation of imagination in Tenniel's Chapter I. The Gift Bestowed and Chapter Three: The Gift Reversed, Furniss avoids such imaginative flights of fancy to focus on the characters of the last Christmas Book. He does not contextualise the action as Clarkson Stanfield does with The Exterior of the Old College, but relies upon closer studies of Redlaw, the street urchin, the Tetterbys, and Milly Swidger to complement the plot involving Redlaw's contaminating others with a curse of forgetting life's sorrows. While Redlaw looks for answers in the fire as he broods over past injustices and betrayals, Furniss's Phantom reads Redlaw himself, studying the causes of his deep depression in preparation for making his offer of forgetfulness.

By the time that Furniss created this illustration of Redlaw and his "doppelganger," the word borrowed from the German had enjoyed currency in English for sixty years, having been introduced in 1851 — some three years after the publication of The Haunted Man. Karl Jung, however, had yet to articulate his concept of "the shadow self," so that the figure of The Phantom anticipates a modern, psychological examination of this traditional figure, whose arrival in folklore usually portends death and misfortune. Furniss has successfully incorporated Redlaw's facial features into the face of the ghostly double while adding a sinister curl to the lip,as if the visitant enjoys Redlaw's brooding over a painful past and draws energy from his melancholia. Dickens was to explore the double in a number of later works, including A Tale of Two Cities (1859) and Great Expectations (1861), but without the supernatural overtones present in his handling of Redlaw's shadow-self or "Phantom."

Left: John Tenniel's Frontispiece; centre, John Leech's "Redlaw and the Phantom" (1848). Right: Felix O. C. Darley's frontispiece for the second volume of Christmas Stories, As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire (1861).

Above: Barnard's "You speak to me of what is lying here," the Phantom interposed.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "John Leech." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. , 1980, 141-51.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910, VIII, 79-157.

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

__________. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

__________. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture Book. Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Created 26 July 2013

Last modified 4 January 2020