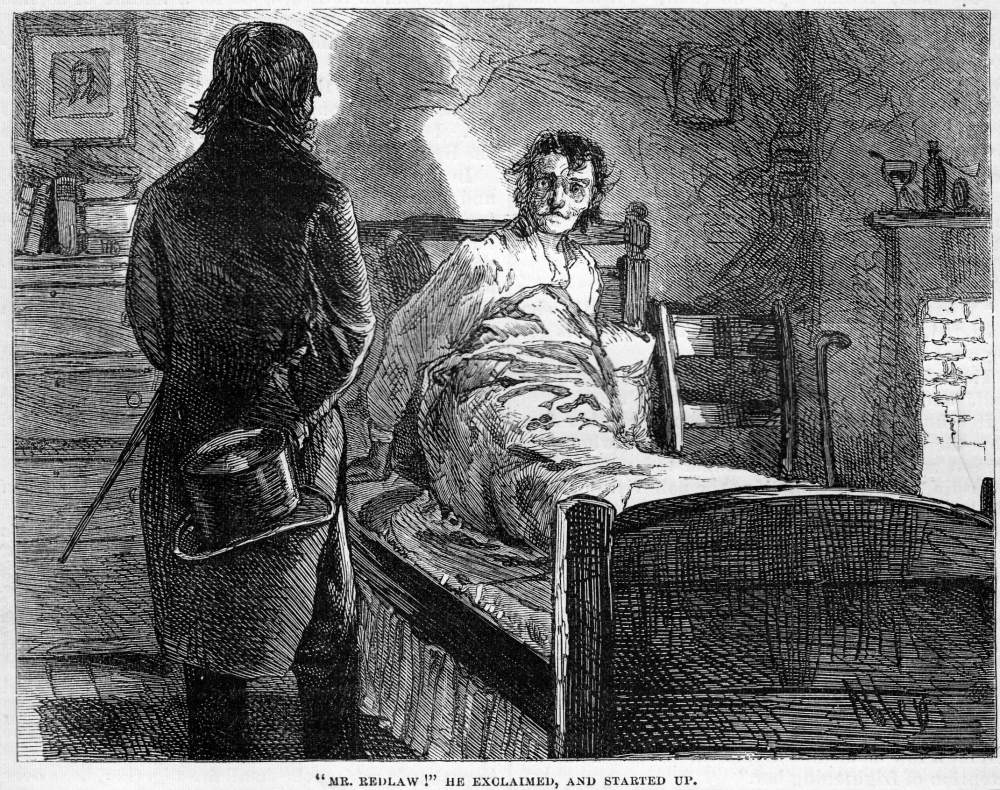

"'Mr. Redlaw!' he exclaimed, and started up" by E. A. Abbey. 10.2 x 13.4 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 158. Dickens's The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain was first published for Christmas 1848. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The Passage Illustrated: The Poor Student Confesses His True Identity

The Chemist glanced about the room; — at the student's books and papers, piled upon a table in a corner, where they, and his extinguished reading-lamp, now prohibited and put away, told of the attentive hours that had gone before this illness, and perhaps caused it; — at such signs of his old health and freedom, as the out-of-door attire that hung idle on the wall; — at those remembrances of other and less solitary scenes, the little miniatures upon the chimney-piece, and the drawing of home; — at that token of his emulation, perhaps, in some sort, of his personal attachment too, the framed engraving of himself, the looker-on. The time had been, only yesterday, when not one of these objects, in its remotest association of interest with the living figure before him, would have been lost on Redlaw. Now, they were but objects; or, if any gleam of such connexion shot upon him, it perplexed, and not enlightened him, as he stood looking round with a dull wonder.

The student, recalling the thin hand which had remained so long untouched, raised himself on the couch, and turned his head.

"Mr. Redlaw!" he exclaimed, and started up.

Redlaw put out his arm.

"Don't come nearer to me. I will sit here. Remain you, where you are!"

He sat down on a chair near the door, and having glanced at the young man standing leaning with his hand upon the couch, spoke with his eyes averted towards the ground.

"I heard, by an accident, by what accident is no matter, that one of my class was ill and solitary. I received no other description of him, than that he lived in this street. Beginning my inquiries at the first house in it, I have found him." ["Chapter Two: The Gift Diffused," American Household Edition, p. 158; British Household Edition, p. 176]

E. A. Abbey's illustration of the Poor Student and Redlaw compared to those by Frank Stone and John Tenniel (1848) and Fred Barnard (1878)

Whereas Dickens's original illustrators — John Leech's, Clarkson Stanfield, John Tenniel, and Frank Stone — were constrained by Dickens's and John Forster's oversight in their productions for the last Christmas Book, the illustrators of the British and American Household Editions of The Christmas Books, Fred Barnard and E. A. Abbey, could offer fresh ideas and realise situations that their predecessors had not. The significant difference in these new programs of illustration lies in very different publishers' conceptions of this Household Edition volume, since, unlike Chapman and Hall two years later, Harper and Brothers attempted to bring together in a single volume much of Dickens's Christmas fiction, not just The Christmas Books of the 1840s, but also the seasonal material that Dickens produced for his weekly journals Household Words and especially All the Year Round. "Typically Dickens wrote a frame narrative and then invited other writers to submit stories fitting the frame" (Davis 68). Although this group, stripped of the complementary stories produced by collaborators for the various Christmas numbers, is generally acknowledged to include some twenty short stories, the American Household Edition contains only nine. Whatever the merits of the New York firm's plans for the volume, Harper and Brothers necessarily limited the number of illustrations that Abbey would be permitted to provide for each of the original Christmas Books, so that, for example, the more modest project at Chapman and Hall enabled Barnard to produce a series of seven large-scale wood-engravings for The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain, while Harper and Brothers restricted Abbey to just three, as opposed to four for each of The Cricket on the Hearth and The Battle of Life. This limitation was undoubtedly at least in part caused by the firm's requesting of Abbey six illustrations for the most celebrated of Dickens's seasonal offerings, A Christmas Carol.

The standard edition of Dickens's works for much of the twentieth century, The Oxford Illustrated Dickens, offers no less than twenty-one short, journalistic pieces in Christmas Stories, originally published in 1959, together with "Thirteen Illustrations by E. G. Dalziel, Townley Green, Charles Green, and others" (title page), notably Household Edition illustrators F. A. Fraser, Harry French, and James Mahoney. Of these reprinted pieces, only ten appear in the Harper and Brothers 1876 volume Christmas Stories: "Somebody's Luggage," "Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings," "Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy," "Doctor Marigold," "Two Ghost Stories" (i. e., "The Trial for Murder" and "The Signal-Man"), "The Boy at Mugby," "The Seven Poor Travellers," "The Holly-tree," and "Going into Society." Admittedly, neither "No Thoroughfare," nor "The Haunted House," nor yet again the unpleasantly racist "Perils of Certain English Prisoners" would seem appropriate to include in the seasonal group, but one wonders why Harpers left out "A Christmas tree," "What Christmas Is As We Grow Older," and "The Poor Relation's Story," all of which have themes involving nostalgia, childhood joys dissolving into adult cares, and the necessity for self-acceptance and foregiveness. And whereas the substantial Oxford volume reprints the entire sequence of each framed tale, including the contribtions of Wilkie Collins and other staff writers, the American Household Edition offers only those portions which Dickens himself wrote, thereby depriving the reader of a coherent story in each instance."

In spite of the limited number of scenes he could realise for the last of the Christmas Books, Abbey's three illustrations highlight the three principal plot lines of the novella, and offer the reader interpretations of no less than eight characters. In the case of Redlaw's meeting the sick student in his rooms in the Jerusalem Buildings, Barnard has created classical chiaroscuro, highlights and Rembrantesque deep shadows, by inserting a roaring fire behind the figures to inject a sense of the numinous, whereas the text (emphasizing the room's unwholesome environment) is quite clear about the inferior heating in the garret:

A meagre, scanty stove, pinched and hollowed like a sick man's cheeks, and bricked into the centre of a hearth that it could scarcely warm, contained the fire, to which his face was turned. Being so near the windy house-top, it wasted quickly, and with a busy sound, and the burning ashes dropped down fast. [British Household Edition, 175-176; American Household Edition, 158]

Above all, Barnard and Abbey fail to realise the despondency of Longford that Stone so effectively communicates in his posture and expression.

Tenniel's atmospheric cartoon and Stone's elegant study versus Barnard's classically modelled portrait and Abbey's more prosaic treatment: left: Tenniel's "Illustrated Double-page"; centre, Stone's "Milly and The Student"; and, right, Barnard's "'Mr. Redlaw!' he exclaimed, and started up".

Frank Stone's analeptic image of the student with a secret pertaining to Redlaw's past shows Longford as deeply depressed and confined to a couch that is not necessarily as "realistic" as Barnard's comfortably padded piece of furniture, but which implies his emotional and physical discomfort. Nevertheless, the striking image of the meeting of the chemistry professor and his student is an important addition to the narrative-pictorial text of the 1848 novella. Barnard, moreover, with artistic license emphasizes the figures by reducing the scale of the student's "couch"; moreover, Barnard offers the sketchiest suggestion of the occupant's belongings and bric-a-brac.

Although E. A. Abbey's treatment of the scene in the American Household Edition may seem more faithful to the text because it includes such personal items and furnishings as Dickens specifies, it shows the room's occupant in a nightshirt and in a single bed, rather than dressed (as in Stone's illustration "Milly and the Student," which must have had Dickens's sanction), and lying on a "couch" (158), as reiterated in the text. Dickens also places the room's sole chair "near the door," rather than by the bed, which in the somewhat crowded wood-engraving effectively blocks Redlaw from advancing upon the student. The student's "books and papers, piled upon a table in a corner" in the text are now on a chest-of-drawers (left); furthermore, although he has subtly placed a medicine bottle on the mantelpiece (right), Abbey has omitted the "extinguished reading-lamp," and the "clothing hanging on the wall," and has made very little of the "little miniatures upon the chimney-piece, and the drawing of home" (158). The principal deviation in the American Household Edition illustration is that Abbey's emaciated Edmund Longford (alias, "Denham") is hardly consistent with the handsome but care-worn youth of Frank Stone's "Milly and The Student" (p. 96). Abbey's tail-coated Redlaw, with respectable middle-class cane and silk hat, facing away from the reader and towards the surprised student, lacks the sense of the ominous and mysterious that Tenniel so effectively conveys in his black-cloaked visitor holding a lantern at the top of the landing in the "Illustrated Double-page to Chapter Two" (page 53). The shadow that the visitor casts upon the wall may be the realist's acknowledgement of the malign influence of the Phantom; the detail appears to be realistic, but in fact there is no source of light in the room to cast such a shadow. Abbey uses the appurtenances of the Victorian gentleman, ther shiny silk hat and cane to establish the identity of the visitor, whose face is hidden from the reader, thereby rendering the figure of the visitor somewhat mysterious. In respect of feeling and atmosphere, then, Barnard's much simpler illustration is closer in spirit to the letterpress, especially in his conveying the numinous and malignant presence of the "pale man in a black cloak" (British Household Edition, p. 174; American Household Edition, p. 157).

However, while Abbey's illustration has the virtue of being presented almost simultaneously with the text it illustrates on page 158 of the American Household Edition, facilitating a reciprocal reading of image and text, Barnard's full-page illustration, facing the text's description of Redlaw's entrance (p. 176), is still analeptic in that it draws on details of Redlaw's attire mentioned earlier; nevertheless, Barnard effectively realises an important textual moment in the emotional trials of the protagonist that the original illustrators failed to underscore. Tenniel leads the reader up the staircase and to the door, as it were, but does reveal what Redlaw finds on the other side, or how he reacts to the revelation that "Denham" is in fact "Longford," the son of his former sweetheart. The "poor student," unlike his more affluent and healthy classmates, has not returned home for the holidays. Utilizing the freedom of Sixties illustrators to interpret a text without absolute fidelity to the text, Barnard and Abbey both must have felt that the original illustrators should have realised the scene in which Redlaw will have to confront the product of a "wrong inflicted on [him]" (159) in his youth, and grapple with powerful emotions that have been numbed by the Phantom's dubious "gift," but which Longford's confession of his true identity now stirs.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Brereton, D. N. "Introduction." Charles Dickens's Christmas Books. London and Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. G. Dalziel, Townley Green, Charles Green, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, and James Mahoney. The Oxford Illustrated Dickens. Oxford, New York, and Toronto: Oxford U. P., 1959, rpt. 1989.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Il. John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

James, Henry. Picture and Text. New York: Harper and Bros, 1893. Pp. 44-60.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 2 January 2013