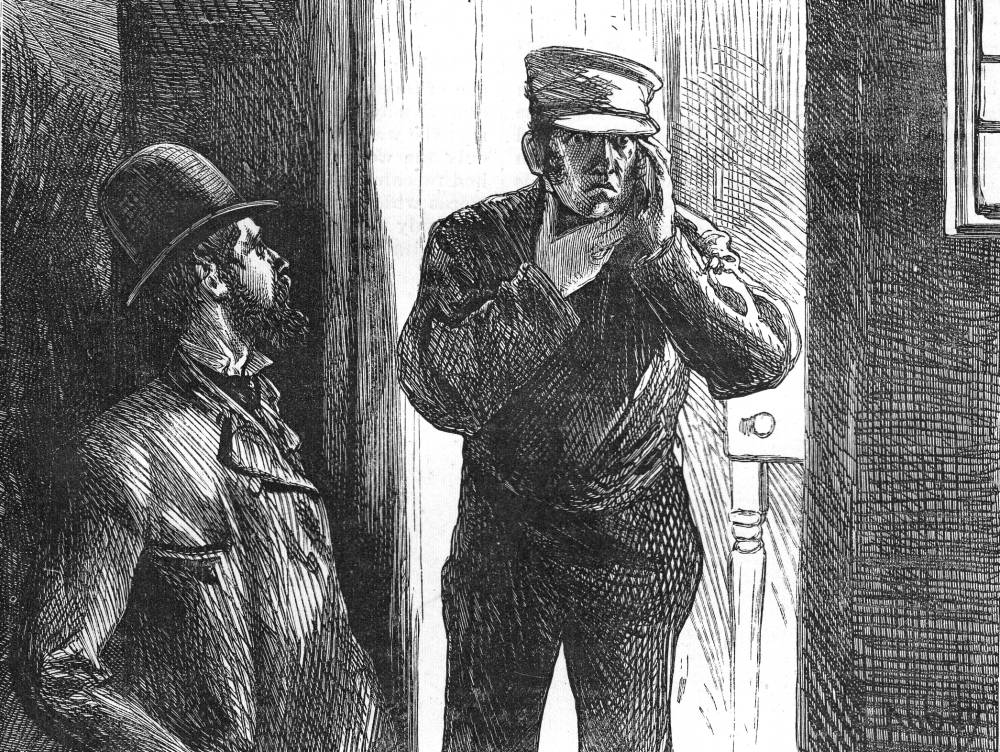

"What would you do with twopence, if I gave it you?" — "Pend it."

Edward G. Dalziel

Wood engraving

13.7 cm high by 10.6 cm wide, framed.

Dickens's "Mugby Junction," in Christmas Stories (1877), p. 201.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

The mysterious face had a voice attached to it, which occasionally led or set the children right. Its musical cheerfulness was delightful. The measure at length stopped, and was succeeded by a murmuring of young voices, and then by a short song which he made out to be about the current month of the year, and about what work it yielded to the labourers in the fields and farmyards. Then there was a stir of little feet, and the children came trooping and whooping out, as on the previous day. And again, as on the previous day, they all turned at the garden-gate, and kissed their hands — evidently to the face on the window-sill, though Barbox Brothers from his retired post of disadvantage at the corner could not see it.

But, as the children dispersed, he cut off one small straggler — a brown-faced boy with flaxen hair — and said to him:

"Come here, little one. Tell me, whose house is that?"

The child, with one swarthy arm held up across his eyes, half in shyness, and half ready for defence, said from behind the inside of his elbow:

"Phoebe's."

"And who," said Barbox Brothers, quite as much embarrassed by his part in the dialogue as the child could possibly be by his, "is Phoebe?"

To which the child made answer: "Why, Phoebe, of course."

The small but sharp observer had eyed his questioner closely, and had taken his moral measure. He lowered his guard, and rather assumed a tone with him: as having discovered him to be an unaccustomed person in the art of polite conversation.

"Phoebe," said the child, "can't be anybobby else but Phoebe. Can she?"

"No, I suppose not."

"Well," returned the child, "then why did you ask me?"

Deeming it prudent to shift his ground, Barbox Brothers took up a new position.

"What do you do there? Up there in that room where the open window is. What do you do there?"

"Cool," said the child.

"Eh?"

"Co-o-ol," the child repeated in a louder voice, lengthening out the word with a fixed look and great emphasis, as much as to say: "What's the use of your having grown up, if you're such a donkey as not to understand me?"

"Ah! School, school," said Barbox Brothers. "Yes, yes, yes. And Phoebe teaches you?"

The child nodded.

"Good boy."

"Tound it out, have you?" said the child.

"Yes, I have found it out. What would you do with twopence, if I gave it you?"

"Pend it." [Mugby Junction, "Barbox Brothers," p. 199]

Commentary

"Young Jackson, otherwise "Barbox Brothers," formerly the senior partner of a Lombard Street brokerage firm, ventures outside the railway junction town of Mugby one morning. Pursuing one of the many intersecting lines from the place, he arrives at a village where he notices children kissing their hands to a singular, horizontally opposed young woman's face in the window of the upper storey of a cottage (right rear in the Dalziel illustration). When he returns to the same spot the next day, the traveller or tourist hears children singing multiplication tables, with the young woman apparently conducting with her hands. Thus, Dickens sets the stage for Barbox's interrogating the rather knowing boy about the young woman's identity, and his subsequently meeting the thirty-year-old Phoebe in "Part 3," "after a lapse of some days" (200). The illustration, then, must be read analeptically since it is situated in "Part 3" although the dialogue that it realizes occurs in "Part 2." Here we and Barbox discover that, owing to some unspecified mobility issue, Phoebe is trapped in her cottage; however, like Tennyson's Lady of Shalott in the 1833 poem (augmented in 1842), Phoebe can imaginatively participate in the activity of the greater world beyond her narrow cottage window by speculating about those whose travels take them past her locale — although their journeys are on the rails rather than the "road that runs by." Although she cannot leave her cottage and her only outlet, besides the village children, is her "art" (lace making), she rejects the label "invalid" as inappropriate because, she maintains, she is not ill.

In successive illustrated anthologies, the often subsequently reprinted short story "The Signal-man" was detached from Mugby Junction, appearing under the heading "Two Ghost Stories." Whereas this landmark cautionary tale for the industrial age was the subject of illustration by Townley Green in the 1868 Illustrated Library Edition, and by E. A. Abbey in the 1876 Harper and Bros. Household Edition, thirty years later Harry Furniss elected instead to illustrate "The Barbox Brothers" and "Barbox Bros. and Co." The multi-part story as it originally appeared on 10 December 1866 was a collaborative effort by the "Conductor" and four of Dickens's staff-writers, who produced four of the "branch lines" or stories associated with the "Mugby" (in fact, Rugby) railway junction. In its original, periodical form the framed tale contained the introduction and two other pieces by Dickens himself — and much extraneous material by his staff-writers at All the Year Round. It did not, as in previous years, have a conclusion written by Dickens, whose chief contribution remains a significant piece of psychological ghost fiction, "The Signal-Man," called "Chapter IV. No. 1 — Branch line."

Andrew Halliday (1830-1877), last represented in the Extra Christmas Numbers by "How the Side-Room was attended by a Doctor" in Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings (1863), contributed "No. 2 Branch Line. The Engine-Driver"; Dickens's son-in-law, painter and writer Charles Allston Collins (1828-1873), "No. 3 Branch Line. The Compensation House"; children's writer Hesba Stretton (the nom de plume of Sarah Smith, 1832-1911), "No. 4 Branch Line. The Travelling Post-Office"; and novelist and journalist Amelia B. Edwards (1831-1892) "No. 5 Branch Line. The Engineer." The organisation of the parts balances Dickens's initial pieces — variously sentimental, satirical, suspenseful and psychological — with the short stories of the younger writers.

Edward Dalziel was Chapman and Hall's chosen illustrator for its own Household Edition volume the year following the publication the Harper and Brothers volume in New York; the British anthology, more extensively illustrated, was dedicated entirely to the Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". E. G. Dalziel's execution of the illustration "What would you do with twopence, if I gave it you?" — "Pend it." for "Barbox Brothers" lacks the playfulness and wit of Dickens's dialogue, and certainly not nearly as mysterious as Furniss's pencil-and-ink sketch of the disembodied head at the upper storey window, which tantalizes the reader but ultimately proves to be the face of a young lace-maker in "Barbox Brothers." The companion stories "Barbox Brothers" and "Barbox Brothers and Co." (chapters one and two in the anthology) were the subjects that Furniss chose to illustrate, despite the fact that these had never been subjects for illustration previously.

Dalziel's focus, unlike Furniss's in The Face at the Window, is not the beautiful, whistful face of the lace-maker, but the elderly "Barbox Brothers" and his precocious interlocutor, reminiscent of so many of Dickens's earlier street boys from Oliver Twist onward. Phoebe's cottage at this point is mere background detail. Strangely enough, Dalziel does not conceive of "Young Jackson" as being the same middle-aged, middle-class traveller as the signal-man's interlocutor in "I took you for some one else yesterday evening. That troubles me." The visitor to the signal-man's telegraph shack in the railway cutting is markedly younger, dressed in contemporary professional class fashion, and has a full beard, whereas the gentleman attempting to extract information from the boy is older, wears classes, and has mutton-chop sideburns. He, too, however, carries an umbrella in his gloved hands, and wears a silk tophat. The real commonality between these flaneur figures is their status as observers, detectives, and reporters, in other words, as stand-ins for the author himself who intercede with various characters in order for them to reveal themselves and their stories.

Relevant Illustrated Library (1868), Household (1876-77), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) Illustrations

Left: Townley Green's "The Signal-Man" (1868). Centre: E. A. Abbey's "Do you see it?" I asked him (1876). Right: Harry Furniss's mysterious illustration "The face at the window" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 10.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller and Additional Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All The Year Round". Illustrated by Townley Green, Charles Green, Fred Walker, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, E. G. Dalziel, and J. Mahony. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1868, rpt. in the Centenary Edition of Chapman & Hall and Charles Scribner's Sons (1911). 2 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition.". New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Charles

Dickens

Visual

Arts

Illustration

The Dalziel

Brothers

Next

Last modified 12 May 2014