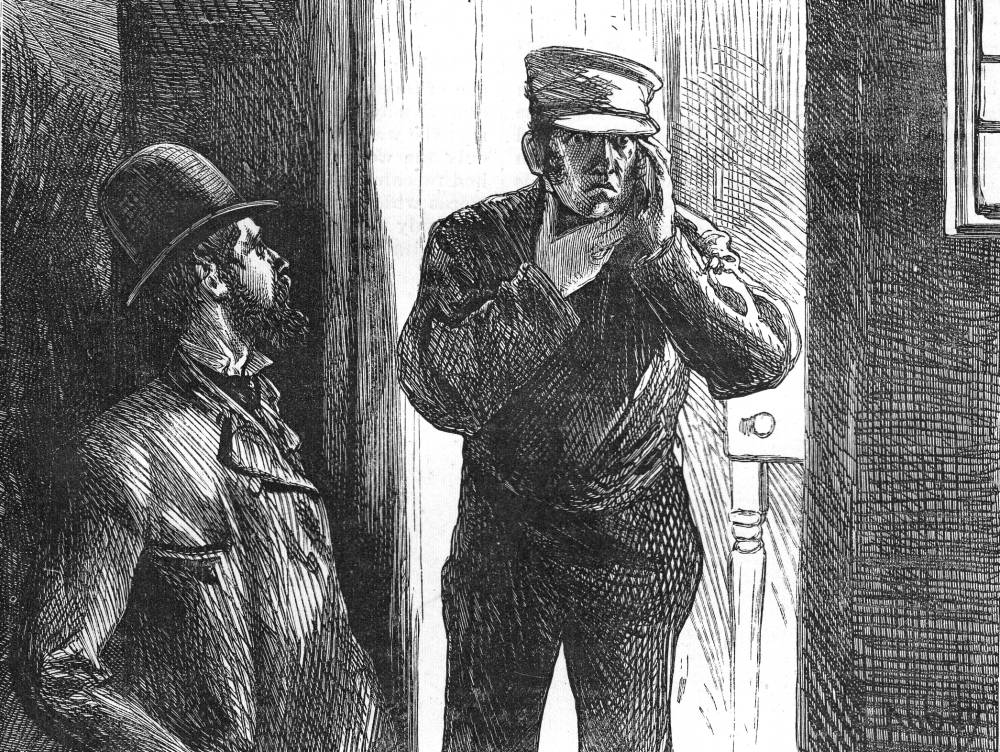

"'Do you see it?' I asked him." by E. A. Abbey. 10.1 x 13.2 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 249. The "tale of the uncanny" originally appeared without illustration in Mugby Junction in the December 1866 "Extra Christmas Number" of All the Year Round. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The story of the haunted railway employee, "No. 1 Branch Line: The Signal-man," is the fourth of four pieces written by Dickens himself in the framed-tale Mugby Junction for the Extra Christmas Number of All the Year Round in 1866, the other three being "Barbox Brothers," "Barbox Brothers and Company," and "Main Line: The Boy at Mugby." This last piece and the techno-Gothic tale "The Signal-man" are the only two reprinted in the American Household Edition. In Abbey's illustration, the gentlemanly narrator (left: a species of flanneur akin to the narrator of The Uncommercial Traveller essays of the 1860s) visits an isolated railway signal-station and makes the acquaintance of its functionary (right: in company uniform) at his post near a tunnel in a cutting on the rail line near "Mugby" (the important railway junction of Rugby in Warwickshire). Mentally and emotionally at the edge, the hapless signal-man is apparently being haunted by some sort of spirit (he terms him merely "the Appearance") who has twice visited him, appearing under his warning light and crying, "Look out!" What the signal-man takes to be the the ghost's third visitation, which occurs shortly after the moment realised in Abbey's illustration, proves fatal to the distraught railway employee. The ominous sense of the preternatural with which Dickens invests the story, so reminiscent of Dickens's collaborator Wilkie Collins, is missing from this solid, three-dimensional closeup of the narrator and the agitated signal-man, who nevertheless stares fixedly at point somewhere behind the reader's right shoulder, as if Abbey means to bring the reader into the frame.

Passage Illustrated

"Will you come to the door with me, and look for it now?"

He bit his under-lip as though he were somewhat unwilling, but arose. I opened the door, and stood on the step, while he stood in the doorway. There, was the Danger-light. There, was the dismal mouth of the tunnel. There, were the high wet stone walls of the cutting. There, were the stars above them.

"Do you see it?" I asked him, taking particular note of his face. His eyes were prominent and strained; but not very much more so, perhaps, than my own had been when I had directed them earnestly towards the same spot.

"No," he answered. "It is not there."

"Agreed," said I.

We went in again, shut the door, and resumed our seats. I was thinking how best to improve this advantage, if it might be called one, when he took up the conversation in such a matter of course way, so assuming that there could be no serious question of fact between us, that I felt myself placed in the weakest of positions.

"By this time you will fully understand, sir," he said, "that what troubles me so dreadfully, is the question, What does the spectre mean?"

I was not sure, I told him, that I did fully understand. [248]

The illustrator must necessarily shift the perspective from first person (that of the investigative narrator) to an objective or dramatic perspective that foregrounds both the narrator and the signal-man. The reader of 1876, if unfamiliar with this series of stories in the 1866 seasonal offering, may well have wondered about the context of this strange ghost story for the Industrial Age, and would not in all likelihood know that that Dickens based this incident on the Clayton Tunnel crash of 1861, although the Household Edition reader might have been aware of Dickens's own involvement in a railway viaduct accident near Staplehurst, Kent, on 9 June 1865.

A tale of the uncanny, Deborah A. Thomas calls "The Signal-man," since it involves the railway functionary's premonition of his own death. Although perhaps technically a "ghost story," it has little in common with Dickens's seasonal offerings of the 1840s. A tightly controlled first-person narrative, an exercise in economy and suspense in the manner of Edgar Allen Poe, it lacks any seasonal association; contains no heart-waring, humanitarian message; and is chiefly psychological in its interest. Indeed, so inward is the eerie story's development that it would seem to defy meaningful illustration. And, indeed, in Abbey's series for Dickens's Christmas Stories the closeup of the middle-class narrator (left, identified by his bowler hat) and the signal-man (right, in corporate uniform) conveys meaning only through the plate's juxtaposition with the letterpress on the facing page (p. 248).

A far more sensational scene would have been the death of the signal-man, but, since this event occurs when the narrator is not present, Abbey may have deemed this dramatic incident unsuitable for illustration, or perhaps too violent, as the arm-waving engine-driver desperately tries to avert the collision, even as the victim ignores his entreaty, believing that the warning — phrased precisely as the phantom has uttered it on two previous occasions — is only in his mind. The picture which Abbey did provide has the virtue of focusing on the story's chief figures, but fails to create the ominous atmosphere of Dickens's text and fails to particularise the setting. Again, Abbey's Sixties style here (particularly his use of highlighting and shadow) is reminiscent of the work of British Household Edition illustrator and engraver Edward Dalziel.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 14 December 2012