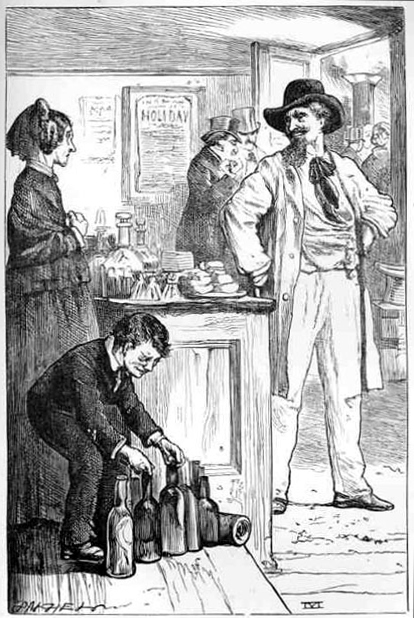

Cotched the decanter out of his hand, and said, "Put it down! I won't allow that!"

Edward G. Dalziel

Wood engraving

13.9 cm high by 10.5 cm wide, framed.

Dickens's "Mugby Junction," in Christmas Stories (1877), p. 216.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

You should see our Bandolining Room at Mugby Junction. It's led to by the door behind the counter, which you'll notice usually stands ajar, and it's the room where Our Missis and our young ladies Bandolines their hair. You should see 'em at it, betwixt trains, Bandolining away, as if they was anointing themselves for the combat. When you're telegraphed, you should see their noses all agoing up with scorn, as if it was a part of the working of the same Cooke and Wheatstone electrical machinery. You should hear Our Missis give the word, "Here comes the Beast to be Fed!" and then you should see 'm indignantly skipping across the Line, from the Up to the Down, or Wicer Warsaw, and begin to pitch the stale pastry into the plates, and chuck the sawdust sangwiches under the glass covers, and get out the — ha, ha, ha! — the sherry, — O my eye, my eye! — for your Refreshment.

It's only in the Isle of the Brave and Land of the Free (by which, of course, I mean to say Britannia) that Refreshmenting is so effective, so 'olesome, so constitutional a check upon the public. There was a Foreigner, which having politely, with his hat off, beseeched our young ladies and Our Missis for "a leetel gloss host prarndee," and having had the Line surveyed through him by all and no other acknowledgment, was a-proceeding at last to help himself, as seems to be the custom in his own country, when Our Missis, with her hair almost a-coming un-Bandolined with rage, and her eyes omitting sparks, flew at him, cotched the decanter out of his hand, and said, "Put it down! I won`t allow that!" The foreigner turned pale, stepped back with his arms stretched out in front of him, his hands clasped, and his shoulders riz, and exclaimed: "Ah! Is it possible, this! That these disdaineous females and this ferocious old woman are placed here by the administration, not only to empoison the voyagers, but to affront them! Great Heaven! How arrives it? The English people. Or is he then a slave? Or idiot?" [Mugby Junction, "The Boy at Mugby," p. 215]

Commentary

"Young Jackson, otherwise "Barbox Brothers," formerly the senior partner of a Lombard Street brokerage firm, interacts with a variety of characters at Mugby Junction, reporting in the refreshment room employee's own words the utter contempt for the travelling public that characterizes that dubious eatery. Whereas James Mahoney in the Illustrated Library Edition had dealt with the confrontation between the boy's supervisor ("The Missis") and a travelling American (his white suit being roughly the visual equivalent of his southern drawl in Dickens's text), and E. A. Abbey had realized her report to her colleagues on the vastly superior food services of the French railways, in the Household Edition Dalziel effectively captures the harridan's chastising a foreigner for his presumption at helping himself to a glass of brandy ("prarndee") at the counter. Against the highly realistic backdrop of the bar and bottles, Dalziel juxtaposes the stern, ancient face of the refreshment room supervisor against the outlandish figure of the foreigner. He is not incredulous; she is not indignant — in this respect, the illustration fails to realise the textual passage. The text through liberal use of Franglais implies that he is French, whereas Dalziel makes him a strange mixture of Italian and Spanish, with straw hat and travelling shawl. Certainly he forms a distinct contrast to Mahoney's white-suited American visually, just as the loquacious Yankee's diatribe about the unpottable nature of the sherry contrasts the European's amazement at the woman's inhospitable behaviour in conjunction with the brandy.

E. G. Dalziel makes the focal point of his composition the decanter, and has the proprietor gesticulate, as if to make her intention clearer to this non-native speaker of English, although Dickens makes him highly voluble in his second language. The Missis shows herself more than a match for all comers, whether English-speakers or foreign travellers. The composition implies that the traveller and the Missis are two continents of experience as her face and figure occupy the left-hand alcove, and those of the stranger to English shores the right alcove. By virtue of his fully drawn figure and bags on the floor in front of the bar, the foreigner should be dominant, but the Missis firmly grasps the decanter, implying her implacable nature and British determination to keep the travelling public down.

In successive illustrated anthologies, the multi-part novella as it originally appeared on 10 December 1866 is considerably reduced since only the contributions of its "Conductor" were reprinted, whereas those of Dickens's four staff-writers, were not. In its original, periodical form the framed tale contained the introduction and two other pieces by Dickens himself — and much extraneous material by his staff-writers at All the Year Round. It did not, as in previous years, have a conclusion written by Dickens, whose chief contribution remains a significant piece of psychological ghost fiction, "The Signal-Man," called "Chapter IV. No. 1 — Branch line."

Andrew Halliday (1830-1877), last represented in the Extra Christmas Numbers by "How the Side-Room was attended by a Doctor" in Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings (1863), contributed "No. 2 Branch Line. The Engine-Driver"; Dickens's son-in-law, painter and writer Charles Allston Collins (1828-1873), "No. 3 Branch Line. The Compensation House"; children's writer Hesba Stretton (the nom de plume of Sarah Smith, 1832-1911), "No. 4 Branch Line. The Travelling Post-Office"; and novelist and journalist Amelia B. Edwards (1831-1892) "No. 5 Branch Line. The Engineer." The organisation of the parts balances Dickens's initial pieces — variously sentimental, satirical, suspenseful and psychological — with the short stories of the younger writers.

Edward Dalziel was Chapman and Hall's chosen illustrator for its own Household Edition volume the year following the publication the Harper and Brothers volume in New York; the British anthology, more extensively illustrated, was dedicated entirely to the Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Even in the 1870s Dalziel was probably aware of Dickens's satire on the poor quality of food and drink that British railways offered the travelling public. Whereas previous illustrators had focused on the plucky youngster, Dalziel decided instead to realize the Missis, whose dictatorial nature E. A. Abbey had captured so well in his parallel illustration for the American Household edition.

Relevant Diamond (1867), Illustrated Library (1868), Household (1876-77), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) Illustrations

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's "The Boy at Mugby" (1867); Right: James Mahoney's "Mugby Junction"; (1868). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: E. A. Abbey's "I noticed that Sniff was agin a-rubbing his stomach with a soothing hand, and that he had drored up one leg" (1876). Right: Harry Furniss's delighted child in "Polly, Barbox Brothers' Guest at Dinner" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 10.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller and Additional Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All The Year Round". Illustrated by Townley Green, Charles Green, Fred Walker, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, E. G. Dalziel, and J. Mahony. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1868, rpt. in the Centenary Edition of Chapman & Hall and Charles Scribner's Sons (1911). 2 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition.". New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Charles

Dickens

Visual

Arts

Illustration

The Dalziel

Brothers

Next

Last modified 14 May 2014