Xit, now Sir Narcissus Le Grand, entertaining his friends on his wedding day — George Cruikshank. Final, double-number, December 1840. Ninety-fourth illustration and thirty-eighth steel-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXXIX. — "Of the wedding of Sir Narcissus Le Grand with Jane the Fool, and what happened at it; and of the entertainment given by him, on the occasion, to his old friends at the Stone Kitchen," summing up the comic plot involving the gigantic warders and their diminutive, vainglorious friend Xit. 9.8 cm high by 14.7 wide, framed, facing p. 407: running head, "Sir Narcissus Interrupted by the Monkey." If the melodrama ends well for Princess Elizabeth, the conclusion of the comic plot is equally satisfying as the dwarf of the Tower marries Queen Mary's Fool — another Jane. The drinking scene dissolves into a discussiuon of preparations for the executions of Lady Jane Grey and her husband — an an anecdote about one of the most celebrated ghosts of the Tower of London, Anne Boleyn. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

Sir Narcissus was then conducted to a seat at the head of the table. On the right was placed his lady, on the left, Dame Placida; while the pantler, who, as usual, filled the office of carver, faced him. The giants were separated by the other guests, and Ribald sat between Dames Placida and Potentia, both of whom he contrived to keep in most excellent humour. Peter Trusbut did not assert too much when he declared that the entertainment should surpass all that had previously been given in the Stone Kitchen; and not to be behindhand, the giants exceeded all their former efforts in the eating line. They did not, it is true, trouble themselves much with the first course, which consisted of various kinds of pottage and fish; though Og spoke in terms of rapturous commendation of a sturgeon's jowl, and Magog consumed the best part of a pickled tunny-fish.

But when these were removed, and the more substantial viands appeared, they set to work in earnest. Turning up their noses at the boiled capons, roasted bustards, stewed quails, and other light matters, they, by one consent, assailed a largo shield of brawn, and speedily demolished it. Their next incursion was upon a venison pasty — a soused pig followed,— and while Gog prepared himself for a copious draught of Rhenish by a dish of anchovies, Magog, who had just emptied a huge two-handed flagon of bragget, sharpened his appetite— the edge of which was a little taken off,— with a plate of pickled oysters. A fawn roasted, whole, with a pudding in its inside, now claimed their attention, and was pronounced delicious. Og, then, helped himself to a shoulder of mutton and olives; Gog to a couple of roasted ruffs; and Magog again revived his flagging powers with a dish of buttered crabs. At this juncture, the strong waters were introduced by the pantler, and proved highly acceptable to the labouring giants. [Chapter XXXIX. — "Of the wedding of Sir Narcissus Le Grand with Jane the Fool, and what happened at it; and of the entertainment given by him, on the occasion, to his old friends at the Stone Kitchen,"pp. 405-406]

Commentary

The Pantler and the Cook, Peter Trusbut and Dame Potentia; Master Hairun, the bearward; the three giant warders, Og, Gog, and Magog; Ribald, and Winwike (without the dark character, Nightgall the Jailer, dead from a ninety-foot fall) now constitute the core of the group who have gathered to celebrate Xit's good fortune, his establishing his identity, and his nuptials. Consequently, Cruikshank has placed the cocky little fellow, a miniature "miles gloriosus," just to the right of centre, beside his wife, Jane, in the present composition. The party in the Stone Kitchen occurs on the day after the wedding, on Sunday, 11 February 1854, in sharp contrast to the political machinations and reversals in the main plot. As Ainsworth remarks, "the bridegroom [is] attired in his gayest habiliments, bedecked at all points with lace, tags, and fringe; curled, scented, and glistening with silver and gold" (402), as he was at the wedding ceremony on the previous day.

Cruikshank depicts the scene after the consumption of the massive wedding feast when well-wishers toast the recently married couple. Cruikshank gives prominenceto the fashionably-dressed bride, Jane the Fool ("Lady Le Grand"), the lavishly dressed bridegroom standing on the table to place himself at her level, and the Pantler (Peter Trusbut) and the Cook(Dame Potentia), raising their glasses (left).Ribald is paying solicitous attention to Lady Le Grand, who seems to be enjoying the celebration, even though Queen Mary had arranged her marriage to the dwarf. The gigantic warders, holding drinking glasses to scale, are seated to the extreme right, around the table, whereas those rather more dour personages associated with executions, torture, and dungeons (Sorrocold, and Wolfytt)together with the chief warder, Winwike, are sitting in a settle, around the corner from the fireplace, left rear. The servant-boy whom Cruikshank has inserted into the proceedings, just left of centre, repeats the figure in the original steel-engraving of the society of the Stone Kitchen, although Ainsworth does not mention this character at all. The precise text upon which Cruikshank is elaborating is the following:

By the time the cloth was removed, and the dishes replaced by flagons and pots of hydromel and wine, Sir Narcissus was in the height of his glory. The wine had got a little into his head, but not more than added to his exhilaration, and he listened with rapturous delight to the speech made by Og, who in good set terms proposed his health and that of his bride. The pledge was drunk with the utmost enthusiasm; and in the heat of his excitement, Sir Narcissus mounted on the table, and bowing all round, returned thanks in the choicest phrases he could summon. [407]

Shortly Ainsworth will shift modes as the three turnkeys begin to discuss the preparations for the forthcoming executions of Lady Jane Grey and her husband. Mauger, the headsman, recalls seeing a ghost on the night before the execution of Catherine Howard: "and I have no doubt it will appear to-night" echoes the opening scenes of Hamlet. Tradition holds that the female figure who issued from the church porch. . . , shrouded from head to foot in white" is that of Anne Boleyn. Thus, the mood of jollity shifts through the joking and anecdotes of Mauger, Sorrocold, and Wolfytt to the serious political issues that will dominate the conclusion of the novel. Ainsworth has the trio explain why Jane and her husband are to be executed in different locations, Jane on Tower Green, Lord Guildford Dudley on Tower Hill: "Lady Jane Grey would be beheaded on Tower Hill, with her husband, but [the authorities] are afraid of the mob, who might compassionate the youthful pair, and occasion a riot" (408). Ainsworth introduces the scene involving the apparition through the conversation of the turnkeys at the wedding banquet:

It has already been stated that Mauger, Sorrocold, and Wolfytt were among the guests. The latter had pretty nearly recovered from the wound inflicted by Nightgall, which proved, on examination, by no means dangerous; and, regardless of the consequences, he ate, drank, laughed, and shouted as lustily as the rest. The other two being of a more grave and saturnine character, seldom smiled at what was going forward; and though they did not neglect to fill their goblets, took no share in the general conversation, but sat apart in a corner near the chimney with Winwike, discussing the terrible scenes they had witnessed in their different capacities, with the true gusto of amateurs. [408]

The three characters drinking in the sttle, upper left, in Xit, now Sir Narcussus Le Grand, entertaining his friends on his wedding day accordingly are Sorrocold, Wolfytt, and Winwike. However, in the text Mauger is clearly a part of the conversation about the "strange tales concerning that place" (408) where the carpenters are going to raise the scaffold. The illustrator therefore should have added the headsman to this low-key group in the corner, since Ainsworth would have intended this part of the illustration in Chapter 39 to prepare the reader for the ghostly "vision" in Chapter 40.

Earlier illustrations involving the characters from the Stone Kitchen

Left: The steel-engraving that introduces the reader to the fanatical Protestant preacher, Edward Underhill the Hot Gospeller preaching to the Giants in the By-ward. (Chapter 6, February 1840). Centre: The steel-engraving depicting the comic cast in a romantic subplot, Magog's Courtship (Chapter 12, April 1840). Right: The comic relief involving Xit's misadventure in the royal menagerie, the steel-engraving in Chapter 19, >Gog extricating Xit from the Bear in the Lions Tower (August 1840). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

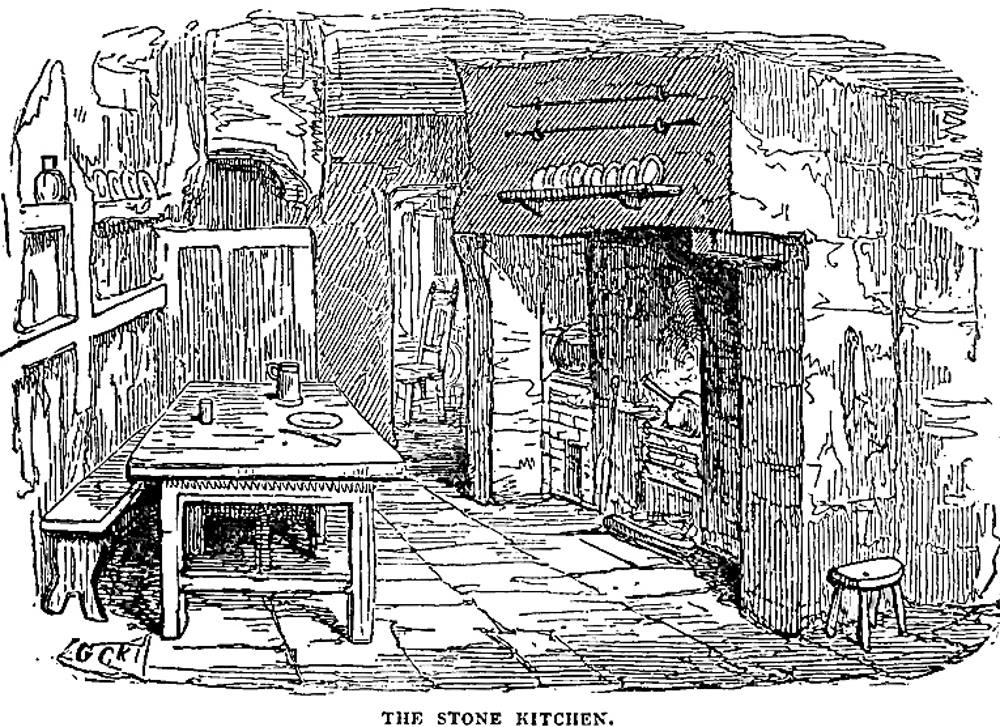

Above: Cruikshank's realistic wood-engraving of the modern-day room in which the Tower's Tudor servants and guards were accustomed to gather, The Stone Kitchen (Chapter 3, January 1840).[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Above: The steel-engraving depicting the comic cast plus the villainous jailer, Nightgall, The Stone Kitchen (January 1840), also in the third chapter of Book the First. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. Accessed 11 September 2017. https://ainsworthandfriends.wordpress.com/2013/01/16/william-harrison-ainsworth-the-life-and-adventures-of-the-lancashire-novelist/

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Jerrold, Blanchard. The Life of George Cruikshank. In Two Epochs. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 4 November 2017