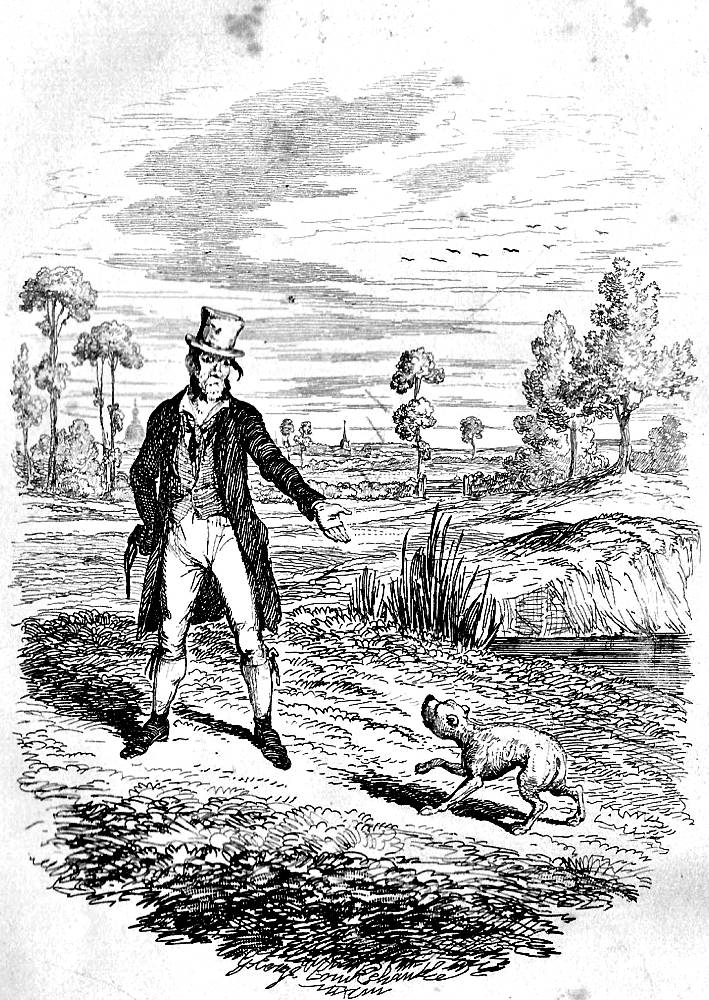

Sikes attempting to destroy his dog — twenty-first steel engraving and later watercolour for Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, first published in volume on 9 November 1838 by Richard Bentley, who then used the engraving again for the January 1839 serial number in Bentley's Miscellany, Part 22, Chapter XLVIII. 4 ⅝ by 3 ½ inches (12 cm by 9 cm), vignetted, facing page 277 in the 1846 single-volume edition. Cruikshank's own 1866 watercolour, commissioned by F. W. Cosens, is the basis for the 1903 chromolithograph. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

- Title-page and frontispiece

- George Cruikshank's coloured Illustrations from 1903 Collector's Edition of Oliver Twist

Passage Illustrated: Sikes Dogged by His Own Conscience Personified

He acted upon this impluse without delay, and choosing the least frequented roads began his journey back, resolved to lie concealed within a short distance of the metropolis, and, entering it at dusk by a circuitous route, to proceed straight to that part of it which he had fixed on for his destination.

The dog, though. If any description of him were out, it would not be forgotten that the dog was missing, and had probably gone with him. This might lead to his apprehension as he passed along the streets. He resolved to drown him, and walked on, looking about for a pond: picking up a heavy stone and tying it to his handerkerchief as he went.

The animal looked up into his master's face while these preparations were making; whether his instinct apprehended something of their purpose, or the robber's sidelong look at him was sterner than ordinary, he skulked a little farther in the rear than usual, and cowered as he came more slowly along. When his master halted at the brink of a pool, and looked round to call him, he stopped outright.

"Do you hear me call? Come here!" cried Sikes.

The animal came up from the very force of habit; but as Sikes stooped to attach the handkerchief to his throat, he uttered a low growl and started back.

"Come back!" said the robber.

The dog wagged his tail, but moved not. Sikes made a running noose and called him again.

The dog advanced, retreated, paused an instant, and scoured away at his hardest speed.

The man whistled again and again, and sat down and waited in the expectation that he would return. But no dog appeared, and at length he resumed his journey. [Chapter XLVIII, "The Flight of Sikes," 277 in the 1846 single-volume edition]

Commentary

Throughout the text Dickens describes Sikes's mixed-breed Bull's-eye as his "white," "shaggy," ever-faithful companion and criminal assistant. Cruikshank has consistently presented him as smooth-haired, but variously as medium-sized and small. Other illustrators have presented more satisfactory and more consistent interpretations of Sikes's canine companion. But their images of the stoutly built, physically powerful, and thoroughly brutal thirty-five-year-old burglar all seem to be based on Cruikshank's conception of a tall, ill-shaven tough wearing a tall, white hat as his continuing feature. The various editions have more continuity in their depictions of the dog than Cruikshank's.

To heighten the contrast between Bill Sikes's terrible, unnatural deed and the blameless lives of working people beyond the metropolis, Dickens transports the tormented burglar and killer to the fields and copses north of London, in the area of Hertfordshire about Hatfield House. Although the Cruikshank illustration of Sikes and his dog may not be as effective as the author would have liked, it underscores the unnaturalness of the urban housebreaker in so natural and uncontaminated a setting. Returning to town upon the eve of the publication of the novel by Richard Bentley in three volumes on 9 November 1838, in a note to the publisher the day before Dickens, having finally reviewed these late illustrations, responded with extreme negativity to just two of the final six: Sikes with his dog, and Oliver with the Maylies, which Dickens firmly requested that the artist thoroughly revise.

Either [Dickens's business agent, John] Forster magnified the author's objections, or Dickens's temper cooled remarkably overnight [i. e., on the evening of 8 November 1838]. In a temperate letter to Cruikshank the next day, he said nothing about Sikes and his dog (which Forster felt resembled a "tail-less baboon" and even [William M.] Thackeray thought badly drawn). Dickens mentioned only the final sentimental scene . . . [Cohen 22]

After the terrifying scene in Chapter 47 in which Sikes brutally assaults Nancy with a pistol butt and then staves her head in with a club, the novel transports Sikes and the reader to the tranquil landscape north of London as Sikes makes his way to Hatfield in Chapter 48. With his unique markings, Bull's-eye is a liability, but the clever dog avoids Sikes' grasp when the ruffian attempts to drown him. However, in spite of his master's changed attitude towards him, Bull's-Eye remains loyal, sticking by Sikes and shadowing him when he returns to the gang's hideout in Jacob's Island on the Thames. While in the little village of Hatfield, near the great house built by Sir Robert Cecil in 1611 (replacing the late 15th c. palace on this site where the future Queen Elizabeth spent part of her childhood, and held her first council of state as monarch in 1558), Sikes visits the nearby Eight Bells, a public house familiar to Dickens when as a young reporter in 1835 he covered the disastrous fire that destroyed much of the Jacobean mansion. Dick Turpin, the infamous highwayman, is reputed to have jumped from the second-storey of The Eight Bells onto his steed, Black Bess, to avoid capture by the Bow Street Runners, an historical feature that may have prompted the young author to associate the brutal burglar with the public house at Hatfield.

Here, the fugitive Sikes hears passengers just alighted from a London coach discussing the recently discovered murder of a woman in Spitalfields, so that he now realizes that hue and cry is about to be raised for him. When a conflagration breaks out in the manor house, Sikes heroically joins the firefighters and works tirelessly to save as much property as possible. Tony Lynch in Dickens' England adds that Dickens uses this occasion to insert what amounts to a topical allusion in having Sikes (perhaps suddenly struck by altruism, but more likely tempting Providence to punish him) fight the fire, for "Dickens was in fact remembering the fire of 1835 at Hatfield House" (109).

Fire engines and crews came from as far away as London to fight the conflagration in which the first Marchioness of Salisbury died. Whereas the meeting of Nancy and Oliver's friends on London Bridge in chapter 46 brings the novel geographically into the world of the reader, the reference to the Hatfield Fire cements the date for the concluding action of the novel as about four years prior to the date of composition. By dramatizing Sikes as one of the firefighters at the bucolic village of Hatfield (perhaps seen on the northern horizon in the Cruikshank illustration for chapter 48) Dickens intersects his own life with that of one of his most notorious villains.

In the much later edition of the novel, Harry Furniss in his 1910 lithographic series offers three illustrations depicting the sensational events following Nancy's murder. He depicts the final days of the Hogarthian blackguard in the dark plate The Death of Nancy, the humorous taproom scene at The Eight Bells in Hatfield, The Flight of Bill Sikes, and the peculiar rendition of Sikes's hanging in which Sikes himself is not in the frame at all, The Death of Sikes.

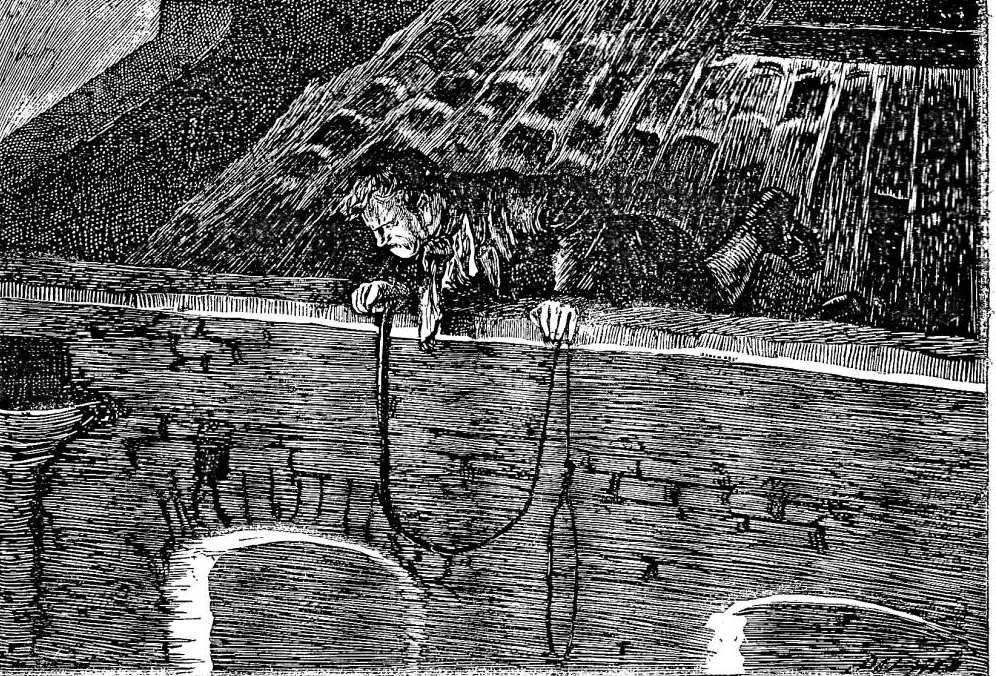

The 1871 Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney depicts Sikes's dragging his dog away from the corpse in He moved backward, towards the door: dragging the dog with him, but does not focus at all upon the murderer's flight northward, resolving Sikes's fate with the scene on the roof-tiles of the gang's hideout at Jacob's Island rookery with And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet. In contrast, Dickens's chief American illustrator, Sol Eytinge, Junior, earlier offered Diamond Edition readers a very different portrait of the dissolute, depressed criminal and his bedraggled doxy in chapter 39, but has no illustrations inserted into the chapters in which Sikes murders Nancy and flees.

Here, Cruikshank provides visual continuity by dressing Sikes in much the same clothing throughout, and consistently pairs Sikes with his dog. Mahoney seems to have chosen to avoid depicting Sikes in these later chapters, for he is clearly seen only in the rooftop scene (without his signature white hat) after his earlier appearances as an intimate associate of Fagin: "You are on the scent, are you, Nancy?" and the robbery scenes at Chertsey, Sikes, with Oliver's hand still in his, softly approached the low porch, and "Directly I leave go of you, do your work. Hark!". The Cruikshank version of Sikes in his penultimate appearance is curiously unemotional, and so much of Dickens's description of him is lacking entirely in the illustration (the noose, the rock, and the futile attempt to entice the dog), so that the criticism that Cruikshank took little care in translating text into image here at least seems fully justified. Nevertheless, wisely Dickens decided not to pick a battle with the illustrator over this drawing, and instead focussed on the demerits of the so-called Fireside plate with which Cruikshank had intended to conclude the narrative-pictorial sequence, by showing Oliver reunited with his relatives, his fortune and identity restored.

Relevant Illustrations from the Diamond, Household, and Charles Dickens Library Editions

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Bill Sikes and Nancy (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition lithograph The Flight of Sikes (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: James Mahoney's And creeping over the tiles, [Sikes] looked over the low parapet (1871). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Material

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, it agitates for social reform

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

Scanned images and text by Simon Cooke, color correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Grego, Joseph (intro) and George Cruikshank. "Sikes attempting to destroy his dog." Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmett's Insurrection in 1803]. London: A. & C. Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Page 88.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Pailthorpe, Frederic W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Patten, Robert L. George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, Volume Two: 1836-1878. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Patten, Robert L. George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1992.

Created 29 December 2014 Last modified 15 January 2022