The Fairy changing Cinderella's Kitchen dress into a beautiful Ball dress!!!. (7.1 cm high by 10.5 cm wide, facing page 12) — the fifth illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1854 and for the third tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. The mice are now milk-white horses, the lizard elegantly clad footmen in eighteenth-century liveries, and the rat-coachman (right) has splendid whiskers; however, as Cinderella points out, there is still a problem: her kitchen-dress and apron are wholly unsuitable for a royal ball at the palace. Significantly, the Fairy Godmother does not re-arrange Cinderella's hair so that she will appear natural in a room full of courtiers with elaborate hair-styles. Moreover, Cruikshank, partly through the juxtaposition of The boot=scraper (lower left) and Cinderella's foot, draws the reader's attention to the act that Cinderella is shoeless, preparing the reader for the Fairy Godmother's presenting Cinderella with the glass slippers.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

Whilst the dwarf was narnessing the mice to the pumpkin, placing the lizards by the side, and putting the rat upon the mushroom, Cinderella was much amused; and when she saw it all move across the kitchen floor, like a little coach and horses, and go out into the road, she was more than surprised: but, when she saw the pumpkin turn into a real coach, and the rat into a real coachman, with a long pig-tail and large mustaches, the mice into milk-white steeds, and the green lizards into tall footmen with their green and gold liveries, she was struck with wonder and astonishment, which was increased, if possible, still more, when, after her godmother had gently touched her with her little cane, or wand, she found all her dingy, rough-working dress changed, in an instant, into one of the most beautiful dresses that can be imagined; her stomacher studded with diamonds, and her neck and arms encircled with the most costly jewels!

Her godmother then took from her tiny pocket a pair of beautiful glass shoes or slippers, and bade Cinderella put them on. Now the soles and lining of these slippers were made of an elastic material, and covered on the outside with delicate spun glass. They were exceedingly small, but Cinderella put them on without difficulty. Her godmother then conducted her to the coach, telling her, as she entered and took her seat upon a beautiful, soft, amber-coloured cushion, to be sure to leave the palace before the clock struck Twelve, and that if she disobeyed or neglected this injunction, the charm would be broken, and she and everything else about her would change back again to their former condition. — "Cinderella and The Glass Slipper," pp. 13-14.

The Perrault Context

She had no sooner done so but her godmother turned them into six footmen, who skipped up immediately behind the coach, with their liveries all bedaubed with gold and silver, and clung as close behind each other as if they had done nothing else their whole lives. The fairy then said to Cinderella, "Well, you see here an equipage fit to go to the ball with; are you not pleased with it?"

"Oh, yes," she cried; "but must I go in these nasty rags?"

Her godmother then touched her with her wand, and, at the same instant, her clothes turned into cloth of gold and silver, all beset with jewels. This done, she gave her a pair of glass slippers, the prettiest in the whole world. Being thus decked out, she got up into her coach; but her godmother, above all things, commanded her not to stay past midnight, telling her, at the same time, that if she stayed one moment longer, the coach would be a pumpkin again, her horses mice, her coachman a rat, her footmen lizards, and that her clothes would become just as they were before.

She promised her godmother to leave the ball before midnight; and then drove away, scarcely able to contain herself for joy. — Chales Perrault, "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper."

Commentary

In 1853-4 and 1864 he flattered his ambition by the issue of "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Unfortunately Ruskin was displeased with the earlier issues of this "library," for in 1857 he forbade his disciples to copy Cruikshank's designs for "Cinderella," "Jack and the Beanstalk" and "Tom Thumb" [sic] as being "much over-laboured and confused in line." But on July 30, 1853, Mrs. Cowden Clarke begged Cruikshank to allow her to thank him in the name of herself "and," writes she, "the other grown-up children of our family, together with the numerous little nephews and nieces who form the ungrown-up children among us, for the delightful treat you have bestowed in the shape of the 1st No. of the 'Fairy Library.'" — W. H. Chesson, pp. 155-156.

Now Cruikshank takes readers from the ramshackle kitchen (left) to road outside the house, showing the six footmen and the driver, but not the horses, in the background. In the foreground, left, approximately where the dwarf with the pointed hat was located in the previous frame, The Pumpkin, and the Rat, and the Mice, and the Lizards, being changed by the Fairy, into a Coach, Horses, and Servants, to take Cinderella to the Ball at the Royal palace (above the present illustration), the Fair Godmother raises her wand, pointing out to the viewer the kitchen-dress transformed. In The Fairy changing Cinderella's Kitchen dress into a beautiful Ball dress!!!, Cruikshank depicts the final moment of the transformation, and Cinderella is now ready to depart for the ball with a truly elegant equipage (although the coach still markedly resembles a gigantic pumpkin). However, the dwarf is about to the deliver the cautionary injunction about the danger of remaining past midnight.

The other scenes containing the Fairy Godmother

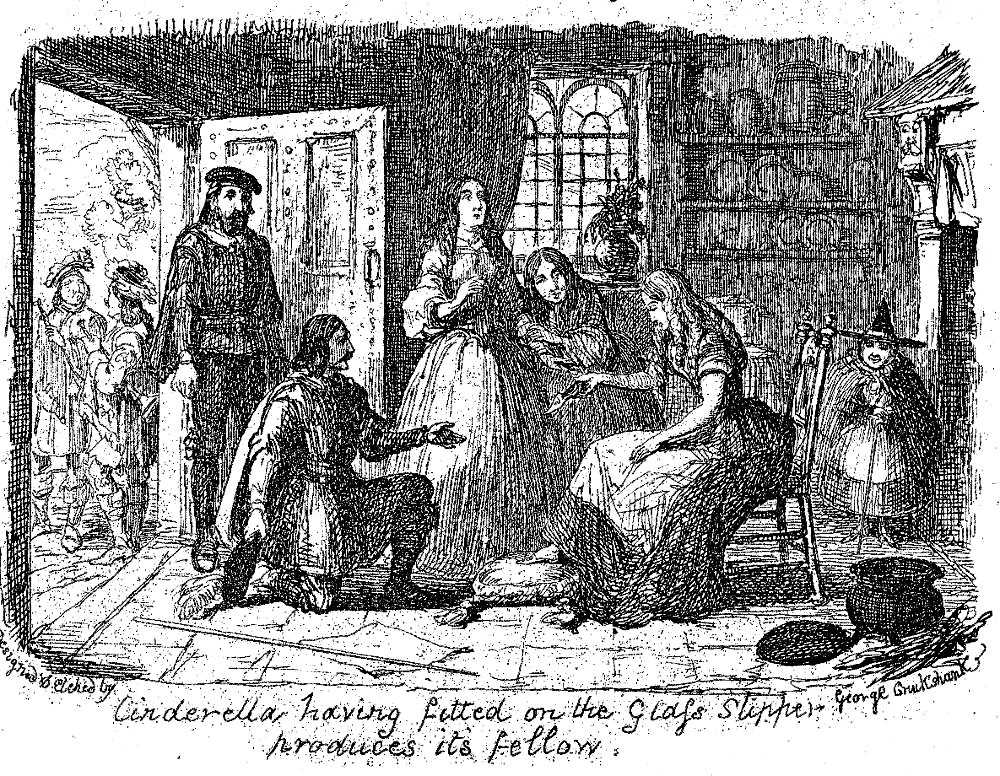

Left: George Cruikshank's initial realisation of the story, frontispiece, Cinderella in the Chimney-Corner (1854). Centre: George Cruikshank's realisation of the Godmother's preparing to transform the pumpkin, rat, mice, and lizards into a splendid equipage, having to perform menial kitchen work, The Pumpkin, and the Rat, and the Mice, and the Lizards, being changed by the Fairy, into a Coach, Horses, and Servants, to take Cinderella to the Ball at the Royal palace (1854). Right: Cruikshank's exciting scene in which the Prince fits the magic slipper on the heroine, with the Fairy Godmother watching the proceedings from the side, Cinderella having fitted on the Glass Slipper produces its Fellow (facing p. 20). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Completely necessary to the effecting of the magical transformation, suggestive of the power of the imagination, is the fairy-guide or mentor, whom Charles Dickens transformed into the ambiguous figures of Magwitch and Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, and the Three Spirits in A Christmas Carol, all of whom are mentors and teachers. Thus, the transformation scene in one of his favourite fairy-tales translated from the French is a key to understanding Dickens's use of fairy-tale patterns for the epiphany of his protagonists in terms not merely of outward transformation but of heightened self-understanding.

In Dickens, the fairy godmother (and godfather) figures are as distorted or peculiar as the dwarf who enacts the role of Cinderella's Fairy Godmother in the Cruikshank version: the sharp-tongued, determined Betsey Trotwood in David Copperfield is both irascible and kind-hearted; the wealthy but deluded Miss Havisham in Great Expectations is only pretending to enact the role for Pip; in fact, Magwitch, whose initial demeanour and appearance are ogre-like, is using his income from the sheep-station in Australia to repay Pip for his kindness in the churchyard. Pip mistakenly assumes that Miss Havisham is his secret benefactor, but she does nothing to disabuse him of the notion so that she intensify the Pockets' enmity. In contrast, the Cheeryble Brothers, Charles and Ned, in Nicholas Nickleby use their influence and wealth for good in an entirely disinterested manner, helping both Nicholas, his sister, and Madeline Bray, in contrast to the personal grievances that motivate Miss Havisham and Abel Magwitch to raise Estella to be a femme fatale and Pip a "gentleman" in vengeance for the way Arthur and Compeyson have treated them. And Old Martin again appears to be an ogre when he is secretly playing the role of godfather for young Martin in Martin Chuzzlewit. In other words, appearances are often deceptive with Dickens's fairy-godmother figures, who, if genuine, are usually working behind the scenes, like the kindly Riah who assists Jenny Wren in Our Mutual Friend.

According to Paul Schlicke in The Oxford Companion to Dickens, as a child Dickens would have become familiar with an English translation of the Perrault tale in chapbook, one of those simple, little volumes that fed his starving imagination, and, when he became a Cinderella figure himself in the blacking factory on the Thames during his father's incarceration for debt (1824), would have made him yearn for a Cinderella-like liberation from drudgery.

In fact, as Schlicke notes, Dickens wrote his own version of "Cinderella" in a modern setting, "The Magic Fishbone," in A Hioliday Romance, in which Princess Alicia's dreary, tension-filled existence is transformed by the sudden appearance of quarter-day at the conclusion. However, Dickens's many uses of the rags-to-riches tale would not have come from either the Cruikshank-illustrated German Popular Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1823) or the Cruikshank re-telling of 1854. However, he anticipated Cruikshank's handling of the transformation scene in his own "Frauds on the Fairies" in Household Words for 1 October 1853, parodying the enlightened positions and progressive causes that Cruikshank was imposing upon such traditional fairy-tales as "Hop-o' My-Thumb" (1853), including her going to court not to dance, but to present the Prince with a temperance petition:

Cinderella ran into the garden, and brought the largest American pumpkin she could find. This virtuously democratic vegetable her grandmother immediately changed into a splendid coach. Then, she sent her for mice from the mouse-trap, which she changed into prancing horses, free from the obnoxious and oppressive post-horse duty. Then, to the rat-trap in the stable for a rat, which she changed to a state-coachman, not amenable to the iniquitous assessed taxes. Then, to look behind a watering-pot for six lizards, which she changed into six footmen, each with a petition in his hand ready to present to the Prince, signed by fifty thousand persons, in favour of the early closing movement. — Charles Dickens (1 October 1853), p. 99.

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Chesson, W. H. "From George Cruikshank's Fairy Library, 'Cinderella,' 1854." George Cruikshank. London: Duckworth, 1920.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Cinderella and The Glass Slipper. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The third volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: David Bogue, 1854. (Price one shilling) 10 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition, Volume 15. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Dickens, Charles. "Frauds on the Fairies." Household Words. A Weekly Journal. Conducted by Charles Dickens.. 1 October 1853. No. 184, Vol. VIII. Pp. 97-100.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition, Volume 5. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kotzin, Michael C. Dickens and the Fairy Tale. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1972.

Perrault, Charles. "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper." Fairy Tales and Other Traditional Stories. Lit2Go. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/68/fairy-tales-and-other-traditional-stories/5089/jack-and-the-bean-stalk/

Schlicke, Paul. "

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 1 July 2017