The Pumpkin, and the Rat, and the Mice, and the Lizards, being changed by the Fairy, into a Coach, Horses, and Servants, to take Cinderella to the Ball at the Royal palace. (6.8 cm high by 9.8 cm wide, facing page 12) — the fourth illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1854 and for the third tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. Even though the creatures are still themselves, already the transformation is occurring: the pumpkin still has mushrooms for wheels, but the rat now has a coachman's whip, the six mice are positioning themselves to pull the carriage, and the four lizards are carrying footmen's staves. Cinderella looks on curiously, holding the door for entourage, whose transformation her Fairy Godmother can complete only once they have left the kitchen. Once again, details of the backdrop establish that this is same room in which the first and second illustrations were set, but the reader sees more of it Cruikshank has, as it were, moved his point of observation back to show both the window and the door, both of which provide sources of light so that the kitchen is now much better illuminated. Significantly, Cruikshank deviates from his likely source, Perrault, in that he delays the transformation of the pumpkin until he has had the Fairy Godmother assemble all of the elements outside the kitchen door.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

The dwarf then said, —

"Run into the garden and fetch me a pumpkin."

Cinderella brought in immediately the largest she could find. The dwarf then took a knife, and having cut a large round hole on each side, scooped out the middle, and placed it upon the ground, with some of the stem upon which the pumpkin grows. She then took five mushrooms, which were lying upon the dresser, and fastened four of them, by means of the tendrils, to the side of the pumpkin, like wheels ; and the fifth she placed in the front, as if for a coach-box. She then told her goddaughter to fetch her the mouse-trap, in which she found six white mice; and having taken a little ball of thread out of her little pocket, she took the mice, one by one, and fastened the thread round their throats, and placed them one behind the other, like a team of horses.

"Now, child!" she said, "run into the garden again, and behind the water-butt, in a fiower-pot, you will find six green lizards, — bring them here."

She did so ; and the dwarf, placing a little bit of straw in the right claw of each, placed two behind the pumpkin, one on each side, and the other two in front of the mice.

"Now," said the little woman, "we want a coach-man ; and if there is a rat in the trap, we'll mount him on the box for a driver."

The trap was brought — there were two in it — and the dwarf, selecting the largest and the fattest, and with the longest tail and whiskers, placed him sitting upright upon the mushroom in the front of the pumpkin ; and then, putting the end of the threads in one of his claws, and a long blade of straw in the other, she told Cinderella to open the kitchen door that led into the road. Then, taking up her little walking-stick in her hand, she waved it three times over the pumpkin, saying, —

"Heigh ho! presto! — go!" and away went the mice, with the pumpkin rolling after them, and the lizards running upon their hind legs, out of the door into the road, followed by the dwarf, who again waved her tiny stick three times, exclaiming, —

"Now, pumpkin, mushrooms, rat, and mice, and lizards, all Change! to a coach-and-six, with servants strong and tall, To take my darling daughter to the Royal Ball."

Whilst the dwarf was narnessing the mice to the pumpkin, placing the lizards by the side, and putting the rat upon the mushroom, Cinderella was much amused; and when she saw it all move across the kitchen floor, like a little coach and horses, and go out into the road, she was more than surprised . . . . — "Cinderella and The Glass Slipper," pp. 11-13.

The Perrault Context

"Well," said her godmother, "be but a good girl, and I will contrive that you shall go." Then she took her into her chamber, and said to her, "Run into the garden, and bring me a pumpkin."

Cinderella went immediately to gather the finest she could get, and brought it to her godmother, not being able to imagine how this pumpkin could help her go to the ball. Her godmother scooped out all the inside of it, leaving nothing but the rind. Having done this, she struck the pumpkin with her wand, and it was instantly turned into a fine coach, gilded all over with gold.

She then went to look into her mousetrap, where she found six mice, all alive, and ordered Cinderella to lift up a little the trapdoor. She gave each mouse, as it went out, a little tap with her wand, and the mouse was that moment turned into a fine horse, which altogether made a very fine set of six horses of a beautiful mouse colored dapple gray.

Being at a loss for a coachman, Cinderella said, "I will go and see if there is not a rat in the rat trap that we can turn into a coachman."

"You are right," replied her godmother, "Go and look."

Cinderella brought the trap to her, and in it there were three huge rats. The fairy chose the one which had the largest beard, touched him with her wand, and turned him into a fat, jolly coachman, who had the smartest whiskers that eyes ever beheld.

After that, she said to her, "Go again into the garden, and you will find six lizards behind the watering pot. Bring them to me."

She had no sooner done so but her godmother turned them into six footmen, who skipped up immediately behind the coach, with their liveries all bedaubed with gold and silver, and clung as close behind each other as if they had done nothing else their whole lives. The fairy then said to Cinderella, "Well, you see here an equipage fit to go to the ball with; are you not pleased with it?" — Chales Perrault, "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper."

Commentary

In 1853-4 and 1864 he flattered his ambition by the issue of "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Unfortunately Ruskin was displeased with the earlier issues of this "library," for in 1857 he forbade his disciples to copy Cruikshank's designs for "Cinderella," "Jack and the Beanstalk" and "Tom Thumb" [sic] as being "much over-laboured and confused in line." But on July 30, 1853, Mrs. Cowden Clarke begged Cruikshank to allow her to thank him in the name of herself "and," writes she, "the other grown-up children of our family, together with the numerous little nephews and nieces who form the ungrown-up children among us, for the delightful treat you have bestowed in the shape of the 1st No. of the 'Fairy Library.'" — W. H. Chesson, pp. 155-156.

Once again, Cruikshank has set the scene set in the ramshackle kitchen, offering considerable detail: previously on the right, the capacious fireplace with a face at the top of its pillar is now on the left, giving us an entirely different perspective on the room. Although the flagstone floor and dresser with platters are the same, Cruikshank shows us aspects of the kitchen not revealed in either Cinderella in the Chimney-Corner (the 1854 frontispiece) or Cinderella scouring the Pots and Kettles (facing page 8). A leaded-pane window looks out on the garden (centre, rear) and a preparation table is immediately adjacent to the hearth — and most significantly we see the doorway leading the road outside house, where, in the next frame, The Fairy changing Cinderella's Kitchen dress into a beautiful Ball dress!!!, Cruikshank depicts the final moment of the transformation, and Cinderella is now ready to depart for the ball with a truly elegant equipage (although the coach still markedly resembles a gigantic pumpkin).

The other scenes set in the kitchen

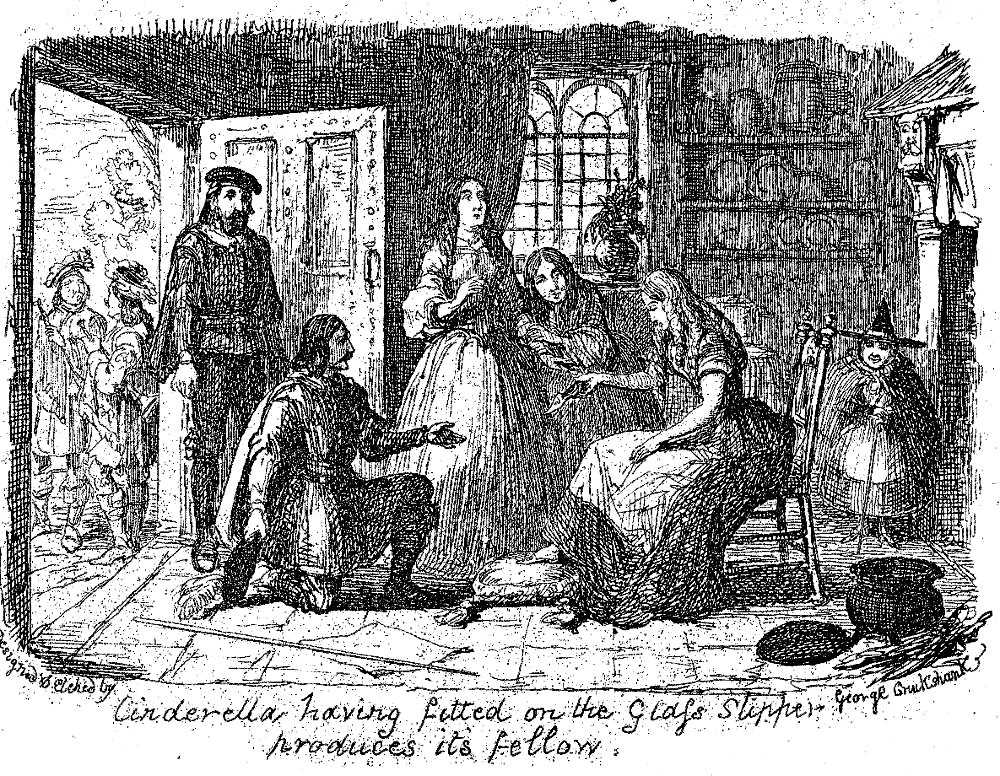

Left: George Cruikshank's initial realisation of the story, frontispiece, Cinderella in the Chimney-Corner (1854). Centre: George Cruikshank's realisation of Cinderella's having to perform menial kitchen work, Cinderella scouring the Pots and Kettles (1854). Right: Cruikshank's exciting scene in which the Prince fits the magic slipper on the heroine, Cinderella having fitted on the Glass Slipper produces its Fellow (facing p. 20). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

In terms of the transformative power of the imagination, the child-like capacity for invention and speculation that Charles Dickens at this time in Hard Times for These Times termed "Fancy," the Perrault version of "Cinderella; or, The Glass Slipper" was one of the most useful fairy-tales for Charles Dickens, and the transformation of the common and everyday into the extraordinary and beautiful was a narrative strategy that served him in many of his stories, from the outward transformation of Cymon Tuggs effected by inheritance in the early short story "The Tuggses at Ramsgate" to the more complex transformations of such young protagonists as Pip in Great Expectations and Amy in Little Dorrit. In Hard Times, the Classroom Ogre, Thomas Gradgrind, deprives his own children of the humanising benefits of fairy-tales in Hard Times, and Scrooge in A Christmas Carol learns to become more capable of sympathy by visiting himself as a lonely, neglected child reading The Arabian Nights. Thus, the transformation scene in one of his favourite fairy-tales translated from the French is a key to understanding Dickens's belief that his art should move readers by appealing to sentiment and imagination, as in his own domestic fairy-tale ("A Fairy-Tale of Hearth and Home") with its humble kitchen scenes of the virtuous Peerybingle family, The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), and throughout his weekly offering in Household Words, announced in his "Preliminary Word" (Saturday, 30 March 1850):

We aspire to live in the Household affections, and to be numbered among the Household thoughts, of our readers. We hope to be the comrade and friend of many thousands of people, of both sexes, and of all ages and conditions, on whose faces we may never look. We seek to bring to innumerable homes, from the stirring world around us, the knowledge of many social wonders, good and evil, that are not calculated to render any of us less ardently persevering in ourselves, less faithful in the progress of mankind, less thankful for the privilege of living in this summer-dawn of time. — No. 1, page 1.

As a child, Judith Smallweed in Bleak House had never heard of "Cinderella," for the cultivation of sentiment and fancy would have gone directly against the grain of the avaricious money-lender Joshua Smallweed and his "sharp practice" ethos.

Cinderella's slipper, the slipper (fur in Perrault's version of the story, glass in the English version) left behind when Cinderella flees from the ball before midnight should strike, and she be changed back into her rags. The love-struck Prince searches through all the realm to find the foot that will fit the slipper, eventually discovering the rightful owner despite obstruction from her Ugly Sisters. — Bentley et al., p. 55.

Dickens specifically alludes to the glass slipper in Dombey and Son, Chapter 6, "Paul's Second Deprivation," when the witch-like Mrs. Brown has stripped Florence of his costly clothing and dressed her in rags, and Florence finds her way to the wharf manager who entrusts her to Walter Gay of her father's business:

Mr. Clark stood rapt in amazement: observing under his breath, I never saw such a start on this wharf before. Walter picked up the shoe, and put it on the little foot as the Prince in the story might have fitted Cinderella’s slipper on. He hung the rabbit-skin over his left arm; gave the right to Florence; and felt, not to say like Richard Whittington — that is a tame comparison — but like Saint George of England, with the dragon lying dead before him.

"Don't cry, Miss Dombey," said Walter, in a transport of enthusiasm. "What a wonderful thing for me that I am here! You are as safe now as if you were guarded by a whole boat's crew of picked men from a man-of-war. Oh, don't cry." — Dombey and Son, pp. 39-40.

Walter Gay, in other words, restores her name and identity to the victimized Florence, as if he were the Prince discovering his bride in the scullery girl. Dickens also alludes to the glass slipper from "Cinderella" in Little Dorrit, Book One, Chapter 2 ("Fellow Travellers"), when the practical but warm-hearted man of business Mr. Meagles recounts how he came to adopt the fancifully-nicknamed Tattycoram:

"So I said next day: Now, Mother, I have a proposition to make that I think you'll approve of. Let us take one of those same little children to be a little maid to Pet. We are practical people. So if we should find her temper a little defective, or any of her ways a little wide of ours, we shall know what we have to take into account. We shall know what an immense deduction must be made from all the influences and experiences that have formed us — no parents, no child-brother or sister, no individuality of home, no Glass Slipper, or Fairy Godmother. And that's the way we came by Tattycoram." — p. 10.

According to Paul Schlicke in The Oxford Companion to Dickens, as a child Dickens would have become familiar with an English translation of the Perrault tale in chapbook, one of those simple, little volumes that fed his starving imagination, and, when he became a Cinderella figure himself in the blacking factory on the Thames during his father's incarceration for debt (1824), would have made him yearn for a Cinderella-like liberation from drudgery.

In 'Frauds on the Fairies' (HW 1 October 1853) he lampooned George Cruikshank's Fairy Library, with its propagation of 'the doctrines of Total Abstinence, Prohibition of the sale of spiritous liquors, Free Trade and Popular Education' within the frame of the traditional tales. . . .— "Fairy Tales," p. 232.

In fact, as Schlicke notes, Dickens wrote his own version of "Cinderella" in a modern setting, "The Magic Fishbone," in A Hioliday Romance, in which Princess Alicia's dreary, tension-filled existence is transformed by the sudden appearance of quarter-day at the conclusion. However, Dickens's many uses of the rags-to-riches tale would not have come from either the Cruikshank-illustrated German Popular Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1823) or the Cruikshank re-telling of 1854. However, he anticipated Cruikshank's handling of the transformation scene in his own "Frauds on the Fairies" in Household Words for 1 October 1853, parodying the enlightened positions and progressive causes that Cruikshank was imposing upon such traditional fairy-tales as "Hop-o' My-Thumb" (1853):

"Alas, grandmother," returned the poor girl, "my sisters have gone to the feast and speeches, and here sit I in the ashes, Cinderella!"

"Never," cried the old lady with animation, "shall one of the Band of Hope despair! Run into the garden, my dear, and fetch me an American Pumpkin! American, because some parts of that independent country, there are prohibitory laws against the sale of alcoholic drinks in any form. Also, because America produced (among many great pumpkins) the glory of her sex, Mrs. Colonel Bloomer. None but an American Pumpkin will do, my child."

Cinderella ran into the garden, and brought the largest American pumpkin she could find. This virtuously democratic vegetable her grandmother immediately changed into a splendid coach. Then, she sent her for mice from the mouse-trap, which she changed into prancing horses, free from the obnoxious and oppressive post-horse duty. Then, to the rat-trap in the stable for a rat, which she changed to a state-coachman, not amenable to the iniquitous assessed taxes. Then, to look behind a watering-pot for six lizards, which she changed into six footmen, each with a petition in his hand ready to present to the Prince, signed by fifty thousand persons, in favour of the early closing movement. — Charles Dickens (1 October 1853), pp. 98-99.

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Chesson, W. H. "From George Cruikshank's Fairy Library, 'Cinderella,' 1854." George Cruikshank. London: Duckworth, 1920.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Cinderella and The Glass Slipper. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The third volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: David Bogue, 1854. (Price one shilling) 10 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition, Volume 15. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Dickens, Charles. "Frauds on the Fairies." Household Words. A Weekly Journal. Conducted by Charles Dickens.. 1 October 1853. No. 184, Vol. VIII. Pp. 97-100.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition, Volume 5. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Perrault, Charles. "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper." Fairy Tales and Other Traditional Stories. Lit2Go. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/68/fairy-tales-and-other-traditional-stories/5089/jack-and-the-bean-stalk/

Schlicke, Paul. "

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 1 July 2017