homas Creswick (1811-69) painted in the idiom of the Picturesque, the eighteenth century tradition that was theorized by William Gilpin and Uvedale Price, developed by artists such as Gainsborough and Richard Wilson, and carried forward by Constable and David Cox. These artists followed the compositional rules of the Picturesque and Creswick similarly adheres to its iconography. Drawing on the many examples of the type, he deploys a semiotic made up of trees (typically placed as framing devices), a well-defined foreground (usually populated with peasants or cattle), a stream, river or pathway, an architectural feature (castle, house, church), a large expanse of sky, and a prospect (often of mountains), or a vista reaching into the far distance.

Some or all of these signs appear in his paintings, and Creswick’s characteristic features were carried over into the black and white of the printed page. The artist divided his work between two main genres: one was the provision of plates for topographical guides and text books, and the other was literary illustration in the form of ‘drawings on wood’ for volumes of poetry.

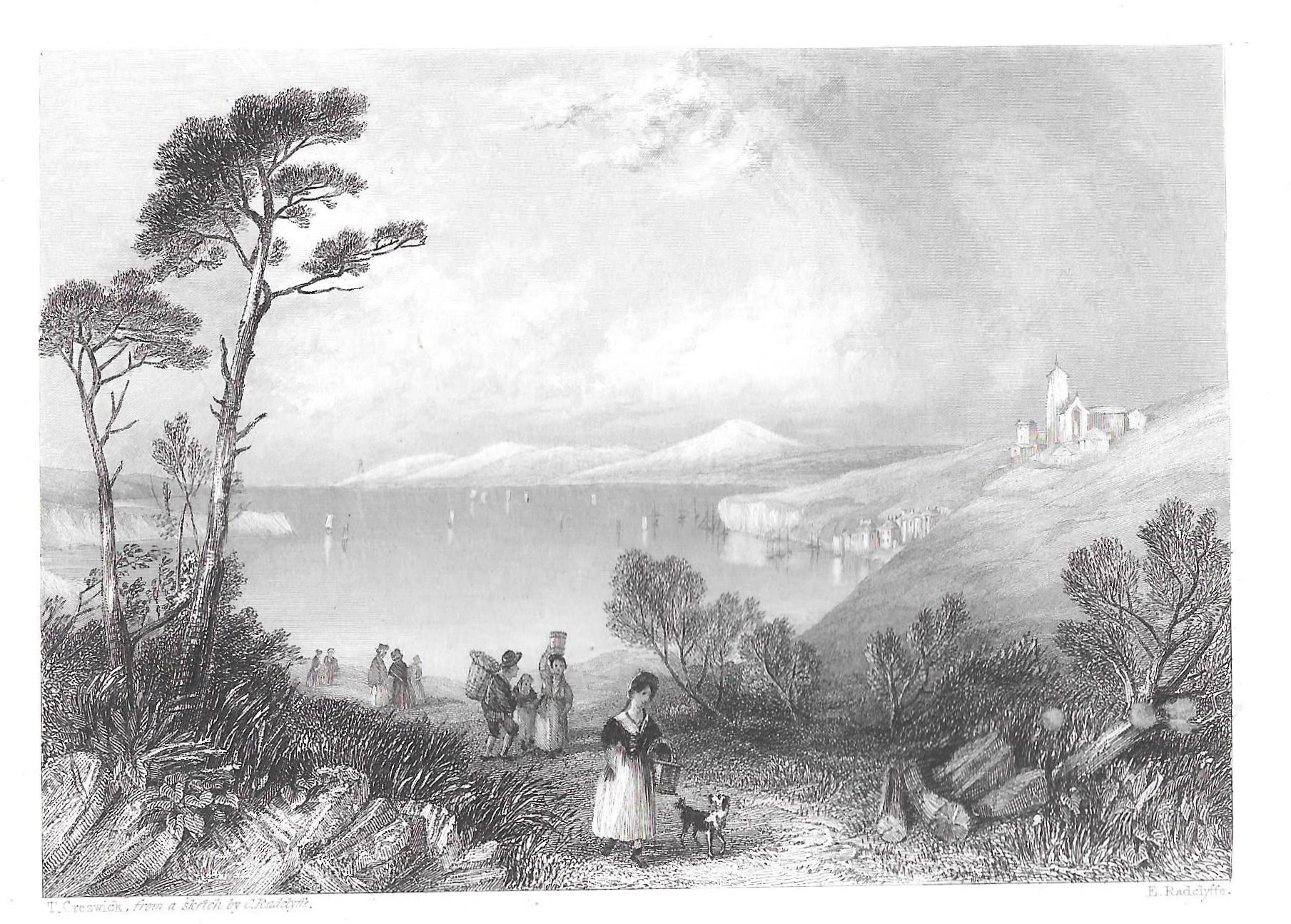

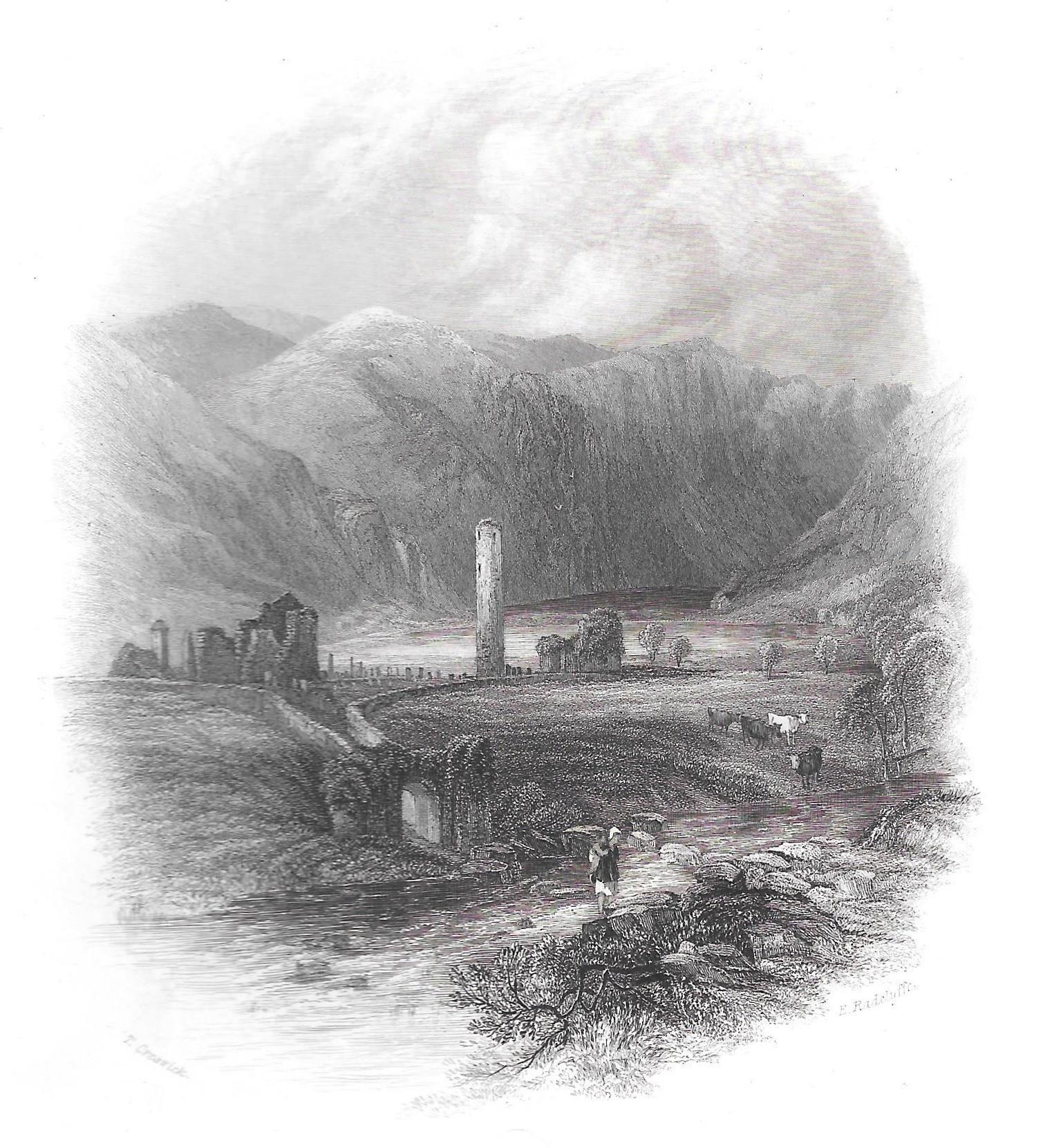

Creswick contributed copper and steel engravings to a wide range of plate books, usually in the company of celebrated contemporaries such as Turner and David Roberts. He is well-represented in Tilt’s Wanderings and Excursions in North Wales (1836), presenting atmospheric views to match Thomas Roscoe’s picturesque travelogue. One of the best of these is Dolbadern Tower – a subject also painted by Turner – in which he combines an impressive panorama of Llanberis with the Romantic remains of Llewelyn’s castle in the middle ground and figures boating in the foreground. He published parallel imagery in Roscoe’s Wanderings in South Wales (1837) and again in S. C. Hall’s Ireland (1846), in each case focusing on the intermingling of landscape and human activity. These books contributed to the aestheticizing of the British landscape, and Creswick was one of those who highlighted the natural poetry of the familiar, the Home Land rather than the landscapes of Europe and beyond.

Left: Creswick’s Milford Haven. Right: The same artist’s Glendalough.

.It is interesting to note, however, that Creswick’s designs were only general equivalents of the letterpress. Some of his plates may have been designed specifically for their context, but the great majority of them are either engravings of paintings or adaptations of paintings. Dolbadern Tower, for example, is a lightly reworked version of an oil depicting the same subject (1836; Sudley House, Liverpool), an image he also modified for Tennyson’s Poems (1857). Engaged in the production of images for canvas or page, Creswick often recycled or adapted material. This approach works well in travelogues, a matter of selecting appropriate subjects and placing them in loose conjunction with the writing.

Creswick’s Dolbadern Castle

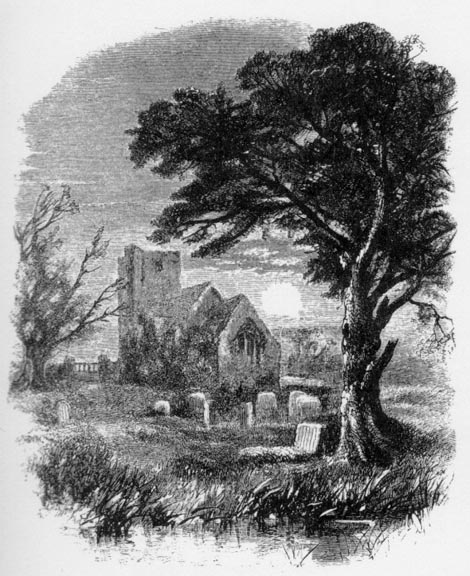

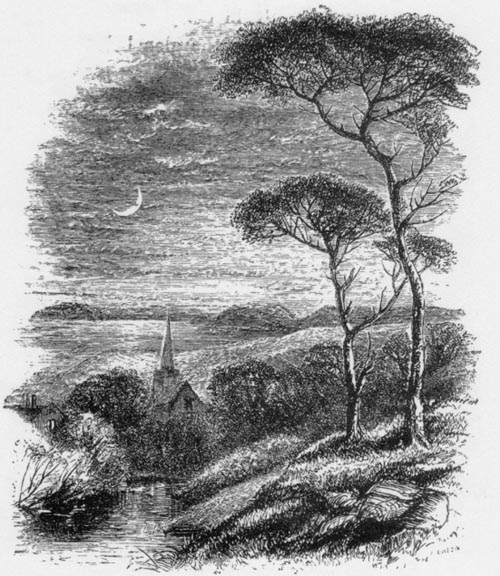

.The issue is more complicated, of course, when it comes to literary illustration, there usually being the expectation that the design should be closely connected with a text, visualizes its subject and elucidates its meanings. In Creswick’s work, however, this process is limited and uneven. In some of his illustrations he clearly sets out to mirror the writing: in his image for Tennyson’s ‘Claribel’, for instance, he depicts the lamented character’s grave, the ‘babbling runnel’ (Poems 1) in the foreground, the trees and the nocturnal setting, with the moon clearly displayed. This reimagining matches Tennyson’s verse in terms of its physical details and its mood. It is more often the case, however, that Creswick focuses only on a tonal equivalent to the literary source – enshrining the atmosphere in natural imagery that acts as an accompaniment rather than offering a direct match. His illustration for another Tennyson poem, ‘Move Eastward’, exemplifies his oblique suggestiveness. The poem is a first person narrative with the narrator anticipating his ‘marriage morn’ following a ‘happy night’ of ‘starry light’ (Poems 372), information Creswick depicts in the form of another nocturne. But in place of other meteorological imagery he shows an idealized English landscape, with a church, a stream and radiating trees. None of these elements are in the poem; but the artist uses them to suggest the narrator’s peaceful state of mind, therein creating an evocative second text to amplify the poem’s emotional effects in which the ‘happy earth’ (Poems 371) becomes a metaphor for contentment.

Left: Claribel; Right: Move Eastward.

He created many other illustrations in the same manner, in each case celebrating the rural idyll in lyrical, delicate designs. Some of the best of these appeared in his engravings for Goldsmith’s Deserted Village (1859) and in Early English Poems (1863). Both volumes contain examples of Creswick’s sensitive art: made up of limited ingredients, he always manages to create a serene atmosphere and sense of place in which well-being and oneness with the natural world can be enjoyed.

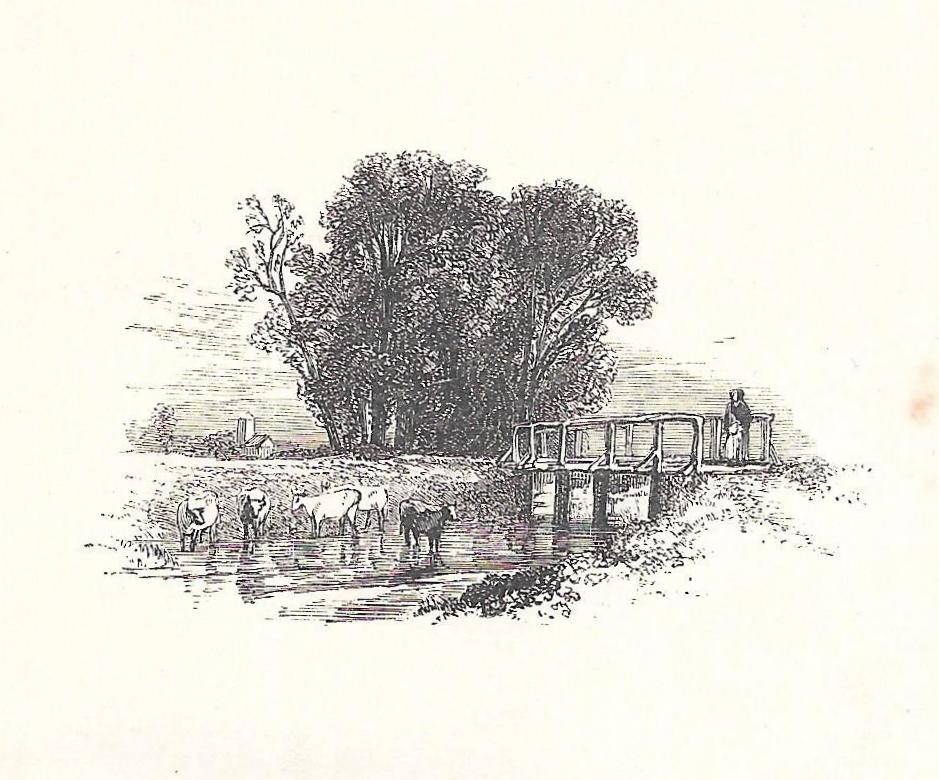

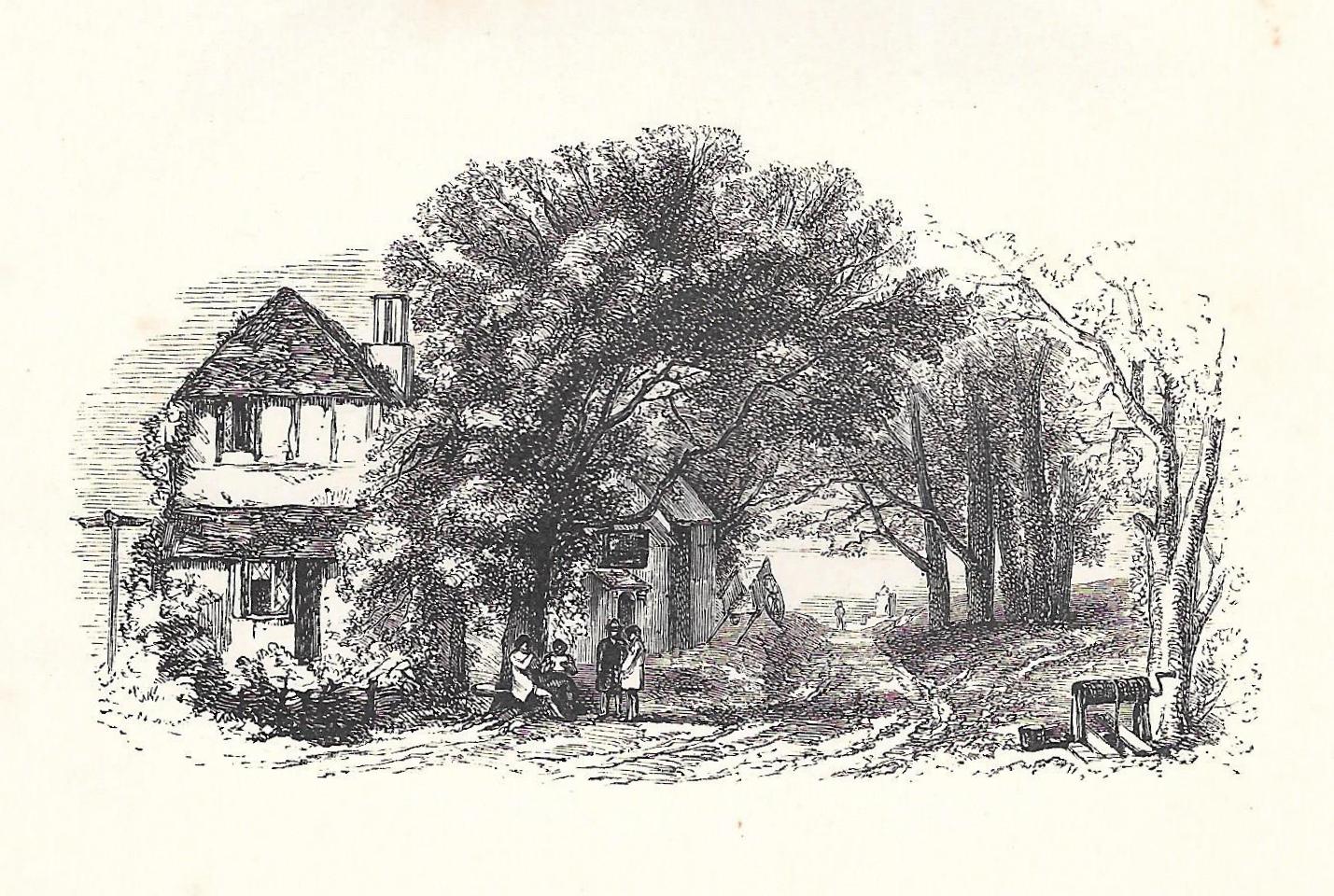

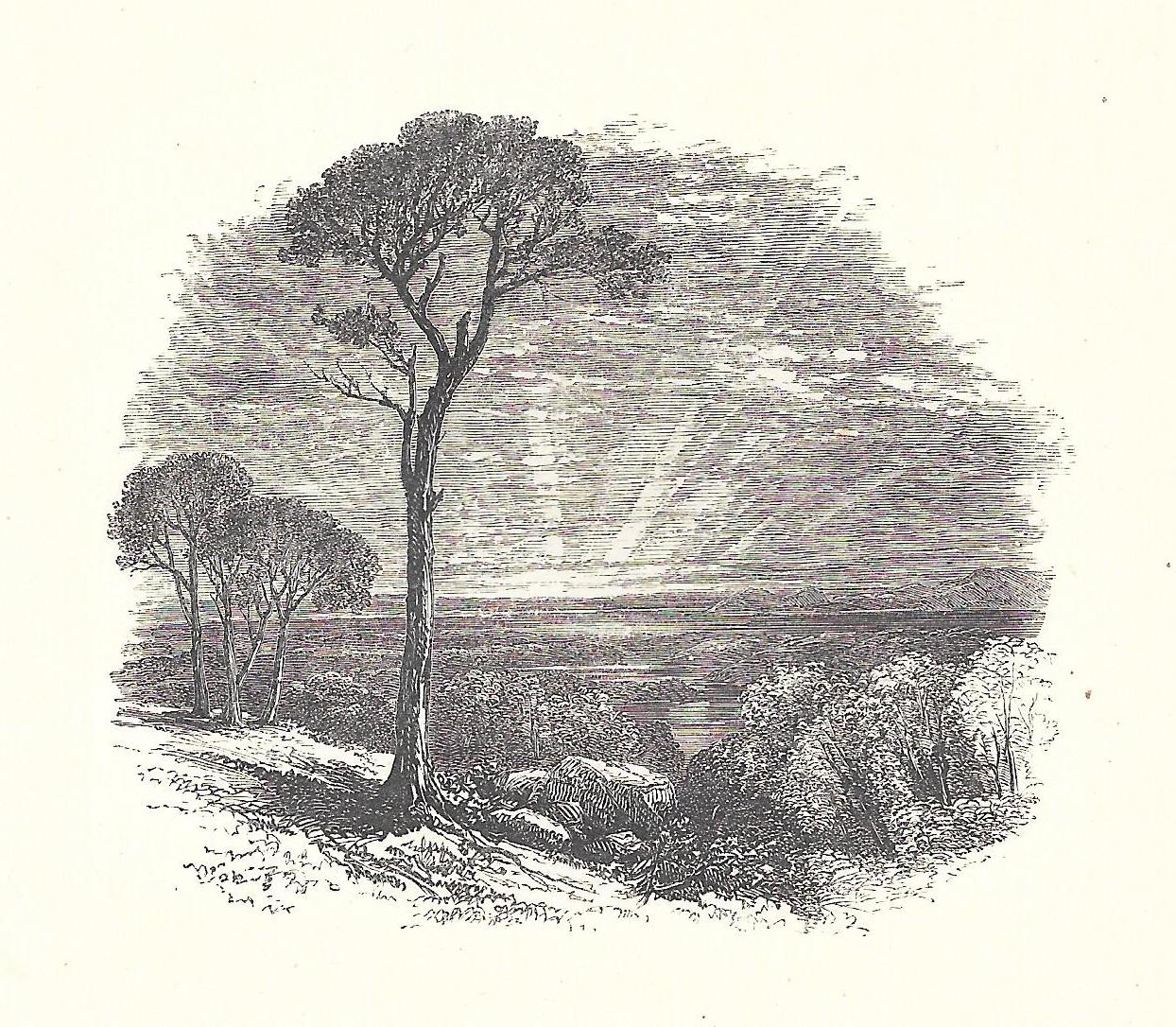

a) A pastoral scene; b) Village Life; c) The Dawn.

This harmonious imagery, carried over his paintings, is Creswick’s most typical response to pastoral verse, and can be traced, notably, in his visualization of Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village (1859). Never required to produce dramatic or tumultuous imagery of the sort typified by Clarkson Stanfield, Creswick’s graphic designs are the work of a quiet and reflective artist whose vision of a pastoral Britain is deeply felt, a minor visual key to accompany the writing of rural themes.

Primary Sources

Books Illustrated by Creswick: a Select List

Early English Poems. London: Sampson Low, 1863.

Hall, S. C. Ireland, Its Scenery, Character, etc.. London: How, 1846.

Goldsmith, Oliver. The Deserted Village. London: Sampson Low, 1859.

Roscoe, Thomas. Wanderings and Excursions in North Wales. London: Tilt, 1836.

Roscoe, Thomas. Wanderings and Excursions in South Wales. London: Tilt, 1837.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857.

Secondary Sources

Maas, Jeremy. Victorian Painters. London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1969.

Created 8 April 2021