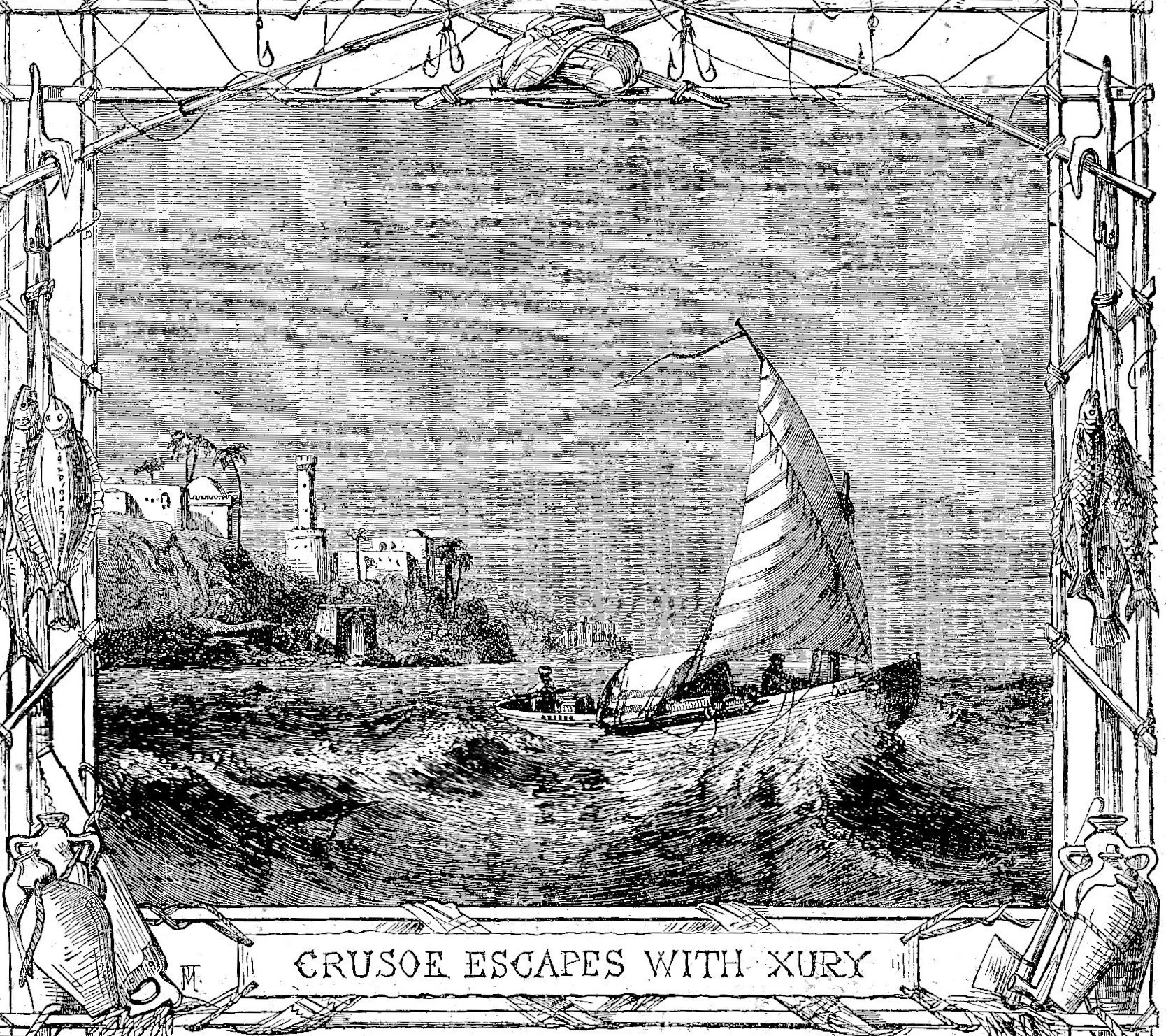

Crusoe escapes with Xury (top of p. 17) — the volume's seventh composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin), 1863-64. Chapter 2, "Slavery and Escape." The illustrator presents a convincing panorama of the stolen Corsair boat and the North African coast, including a minaret, to define the non-European nature of the setting; at this point, the resilient Crusoe, an escaped slave, is a small figure. One of the highly attractive features of the Cassell's volume is ornamental border filled with objects appropriate to the particular adventure; here, fish, a gaff, and Moorish water-jars (all key objects in young Crusoe's escape) add to the verisimilitude of the text. Half-page, framed: 12.5 cm high x 14.2 cm wide, including frame. Running head: "The Lions at their Toilet" (p. 16). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Seizing the opportunity to escape

After we had fished some time and caught nothing— for when I had fish on my hook I would not pull them up, that he might not see them— I said to the Moor, "This will not do; our master will not be thus served; we must stand farther off."He, thinking no harm, agreed, and being in the head of the boat, set the sails; and, as I had the helm, I ran the boat out near a league farther, and then brought her to, as if I would fish; when, giving the boy the helm, I stepped forward to where the Moor was, and making as if I stooped for something behind him, I took him by surprise with my arm under his waist, and tossed him clear overboard into the sea. He rose immediately, for he swam like a cork, and called to me, begged to be taken in, told me he would go all over the world with me. He swam so strong after the boat that he would have reached me very quickly, there being but little wind; upon which I stepped into the cabin, and fetching one of the fowling-pieces, I presented it at him, and told him I had done him no hurt, and if he would be quiet I would do him none. "But,"said I, "you swim well enough to reach to the shore, and the sea is calm; make the best of your way to shore, and I will do you no harm; but if you come near the boat I’ll shoot you through the head, for I am resolved to have my liberty;" so he turned himself about, and swam for the shore, and I make no doubt but he reached it with ease, for he was an excellent swimmer.

I could have been content to have taken this Moor with me, and have drowned the boy, but there was no venturing to trust him. When he was gone, I turned to the boy, whom they called Xury, and said to him, "Xury, if you will be faithful to me, I'll make you a great man; but if you will not stroke your face to be true to me," that is, swear by Mahomet and his father's beard, "I must throw you into the sea too." The boy smiled in my face, and spoke so innocently that I could not distrust him, and swore to be faithful to me, and go all over the world with me.

While I was in view of the Moor that was swimming, I stood out directly to sea with the boat, rather stretching to windward, that they might think me gone towards the Straits' mouth (as indeed any one that had been in their wits must have been supposed to do): for who would have supposed we were sailed on to the southward, to the truly barbarian coast, where whole nations of negroes were sure to surround us with their canoes and destroy us; where we could not go on shore but we should be devoured by savage beasts, or more merciless savages of human kind. [Chapter II, "Slavery and Escape," pp. 15-16]

Commentary

The illustration of the African shore with its minaret and palm trees continues the nautical theme, implying that the novel will be concerned with voyages to foreign ports and adventures on the high seas. Indeed, if one regards shipping, shipwrecks, the sea, and sailors as a construct behind the illustrations, about thirty per cent of the Cassell's illustrations are associated with such a motif. A further twenty percent of the narrative-pictorial series involves foreigners and foreign locales.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from the 1815 & 1818 Children's Books, Cruikshank (1831), and Wehnert (1862)

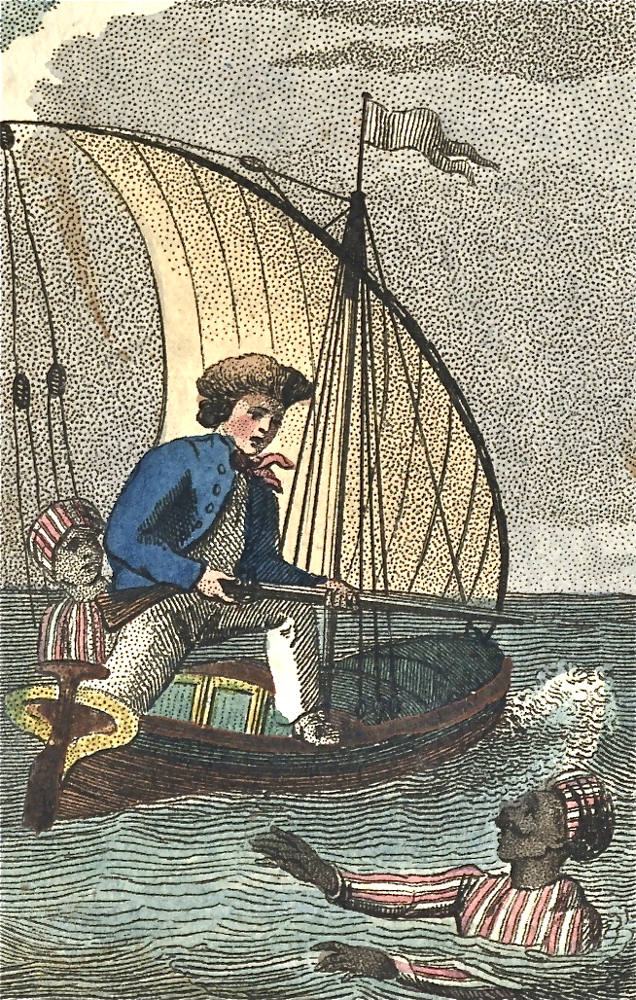

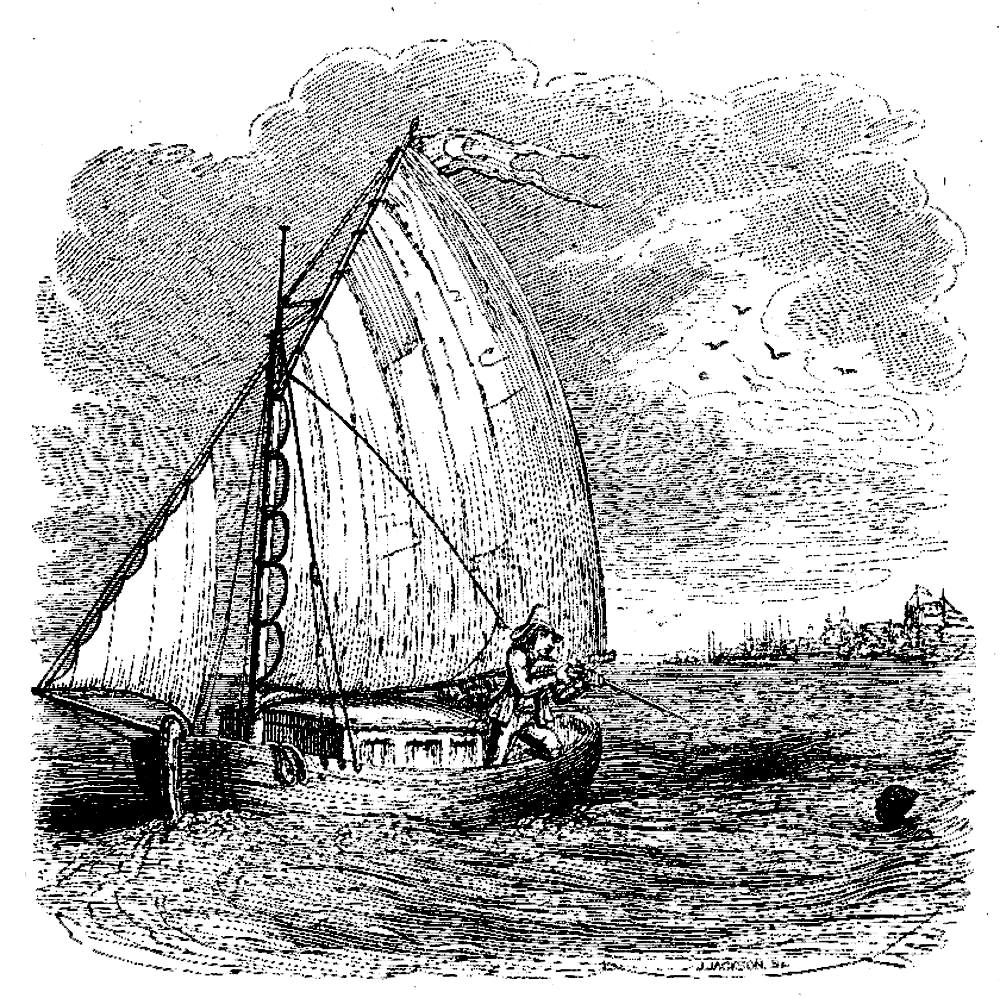

Left: Colourful children's book realisation of the same episode, Robinson Crusoe's escaping from Sallee (1818). Centre: A Chapbook-like woodblock engraving with broken chains, signifying young Crusoe's escaping slavery, Robinson Crusoe throwing the Moor overboard (1815). Right: Wehnert's realisation of the same scene, with a highly realistic and dynamic interpretation: Crusoe throwing the Moor overboard (1862). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Cruikshank's vignette of Crusoe's making a break for freedom, Crusoe tosses the Moorish deckhand overboard (1831). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

De Foe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 8 March 2018