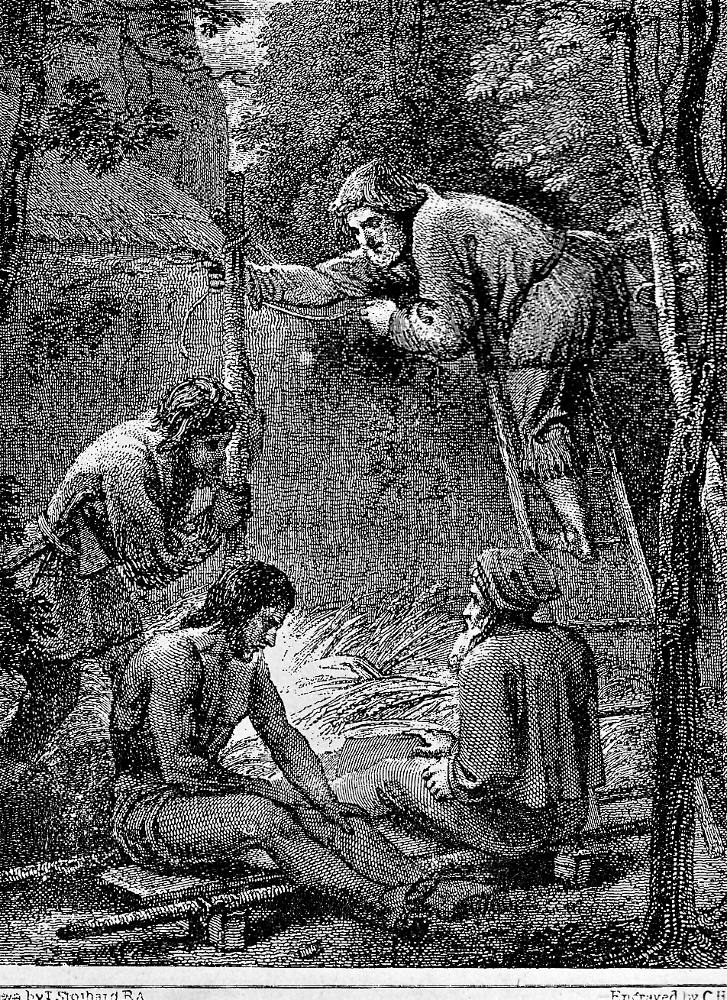

Crusoe discovers himself to the English captain (page 169) — the volume's forty-fifth composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Chapter XVII, "The Visit of the Mutineers." The conventional chapter title prepares readers for Crusoe's rescue from an unexpected quarter, and the subsequent running head ("Deliverance in an Uncouth Form," p. 171) suggests that the three sailors upon whom Crusoe stumbles will assist him in returning to England. The illustrator minimizes the jungle setting to focus on Crusoe, just right of centre, and the English sea-captain to the left of centre. Full-page, framed: 14 cm high (including caption) x 21.8 cm wide, including the framing border to the right and left featuring tropical plants as a theatrical curtain.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated

It was my design, as I said above, not to have made any attempt till it was dark; but about two o’clock, being the heat of the day, I found that they were all gone straggling into the woods, and, as I thought, laid down to sleep. The three poor distressed men, too anxious for their condition to get any sleep, had, however, sat down under the shelter of a great tree, at about a quarter of a mile from me, and, as I thought, out of sight of any of the rest. Upon this I resolved to discover myself to them, and learn something of their condition; immediately I marched as above, my man Friday at a good distance behind me, as formidable for his arms as I, but not making quite so staring a spectre-like figure as I did. I came as near them undiscovered as I could, and then, before any of them saw me, I called aloud to them in Spanish, "What are ye, gentlemen?" They started up at the noise, but were ten times more confounded when they saw me, and the uncouth figure that I made. They made no answer at all, but I thought I perceived them just going to fly from me, when I spoke to them in English. "Gentlemen," said I, "do not be surprised at me; perhaps you may have a friend near when you did not expect it." "He must be sent directly from heaven then," said one of them very gravely to me, and pulling off his hat at the same time to me; "for our condition is past the help of man." "All help is from heaven, sir," said I, “but can you put a stranger in the way to help you? for you seem to be in some great distress. I saw you when you landed; and when you seemed to make application to the brutes that came with you, I saw one of them lift up his sword to kill you."

The poor man, with tears running down his face, and trembling, looking like one astonished, returned, "Am I talking to God or man? Is it a real man or an angel?" [Chapter XVII, "The Visit of the Mutineers," p. 171]

Commentary

Although the Cassell's treatment is more natural, it still smacks of the theatricality of the 1831 Cruikshank realisation of this moment, Crusoe and Friday encounter the captain of a British ship whose crew have mutinied not only in its curtain-like side borders, but in the disposition and poses of the characters. The slight backdrop conveys little sense of depth or perspective, drawing the eye forward to the well-armed, goatskin-clad Crusoe and the captain, who has just doffed his hat out of respect for this strange apparition. Although Friday looks on curiously, right rear, Pasquier draws the viewer's attention to the more sharply defined figures of the sailors, individualised by their postures and attitudes. The man to the left grips his companion's shoulder, anxious to hear what the stranger has to say and learn whether he brings relief or further danger. The other sailor's keeping his hands on his hips suggests a more defiant attitude, but he too stares pointedly at Crusoe.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from other 19th century editions, 1790-1891

Above: George Cruikshank's more explicit indication of how Crusoe will at last be able to leave the island, Crusoe and Friday encounter the captain of a British ship whose crew have mutinied (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Wal Paget's dramatic lithograph of Crusoe's hailing three sailors in seventeenth-century clothing, in a scene that could have come from his Treasure Island illustrations, "What are ye, gentlemen?" (1891). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of another significant meeting at the end of the first book, Robinson Crusoe and Friday making a tent to lodge Friday's father and the Spaniard (Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the Prisoners from the Cannibals," copper-engraving). Centre: In the children's book illustration, the Captain offers Crusoe his ship without any reference to quelling the mutiny first, The Captain offers a Ship to Robinson Crusoe (1818). Right: In the 1820 children's book illustration, The poor man, with a gush of tears, answered, "Am I talking to a man or an angel?", Crusoe (in oversized goatskin hat) and Friday (marginalised) encounter the victims of the mutiny. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 19 March 2018