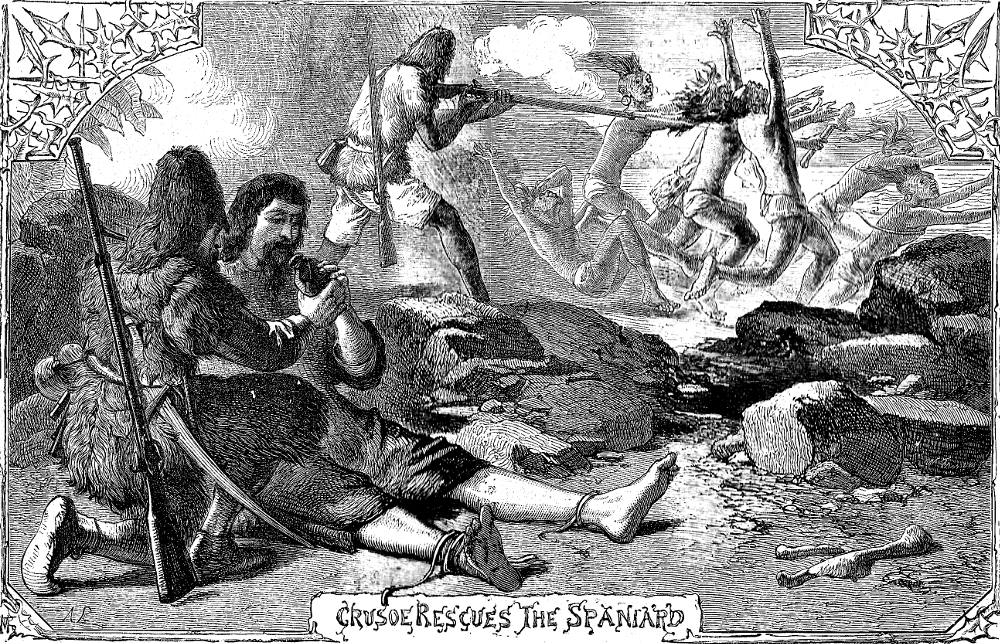

Crusoe rescues the Spaniard (page 157) — the volume's forty-second composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the prisoners from the Cannibals." Although the conventional chapter title emphasizes the rescue of two prisoners, the European and Carib (who by coincidence turns out to be Friday's father), nineteenth-century British illustrations tend to focus on Crusoe's coming to the aid of the cannibals' Spanish prisoner. Although George Cruikshank depicts the later reunion of Friday and his father, he is much more concerned with Crusoe and Friday conducting surveillance on the cannibals prior to launching their attack to liberate the bearded (and, therefore, European) prisoner. Full-page, framed: 14.2 cm high (including caption) x 21.8 cm wide, including the border featuring thorns in the corners. Running head: "The Spaniard saved" (page 159).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated

While my man Friday fired at them, I pulled out my knife and cut the flags that bound the poor victim; and loosing his hands and feet, I lifted him up, and asked him in the Portuguese tongue what he was. He answered in Latin, Christianus; but was so weak and faint that he could scarce stand or speak. I took my bottle out of my pocket and gave it him, making signs that he should drink, which he did; and I gave him a piece of bread, which he ate. Then I asked him what countryman he was: and he said, Espagniole; and being a little recovered, let me know, by all the signs he could possibly make, how much he was in my debt for his deliverance. “Seignior,” said I, with as much Spanish as I could make up, “we will talk afterwards, but we must fight now: if you have any strength left, take this pistol and sword, and lay about you.” He took them very thankfully; and no sooner had he the arms in his hands, but, as if they had put new vigour into him, he flew upon his murderers like a fury, and had cut two of them in pieces in an instant; for the truth is, as the whole was a surprise to them, so the poor creatures were so much frightened with the noise of our pieces that they fell down for mere amazement and fear, and had no more power to attempt their own escape than their flesh had to resist our shot; and that was the case of those five that Friday shot at in the boat; for as three of them fell with the hurt they received, so the other two fell with the fright. [Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the prisoners from the Cannibals," p. 159]

Commentary: Friday Tested Under Fire

Various illustrators have interpreted the second and equally dramatic rescue scene in which Crusoe eschews cultural non-intervention in favour of rescuing a fellow European and Christian. So quickly has Friday picked up the essentials of handling European weaponry and tactics that Crusoe can devote himself to tending the prisoner while his servant puts half-a-dozen cannibals into panic-stricken flight. Friday's prey in Pasquier's illustration do not seem to be aware that, since he has fired both weapons, their own tomahawks and superior numbers would easily carry the day against their assailant. Although Friday's calves are bare, the rest of his attire resembles Crusoe's, right up to the goatskin cap, so that, as far as the cannibals are concerned, the being discharging his strange and powerful weapon is another god-like outlander rather than the member of a rival tribe. The illustration, then, marks the success of Crusoe's educating Friday to become a thoroughly dependable, Europeanized servant.

While Friday discharges his long-barrelled rifle at the fleeing tribesmen in the background, in the foreground a heavily-armed Crusoe disregards the danger in which he has placed his servant in order to minister to the captive, whose bonds he has just cut. Opposite them, down right, several conspicuous bones point to the fact that this is where the mainland cannibals typically conduct their grisly rites. The meaning of the thorns in the corners of the frame Pasquier leaves to the reader's conjecture. Perhaps the illustrator intends them to represent the more unsavoury side of this island paradise.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from other 19th century editions, 1790-1891

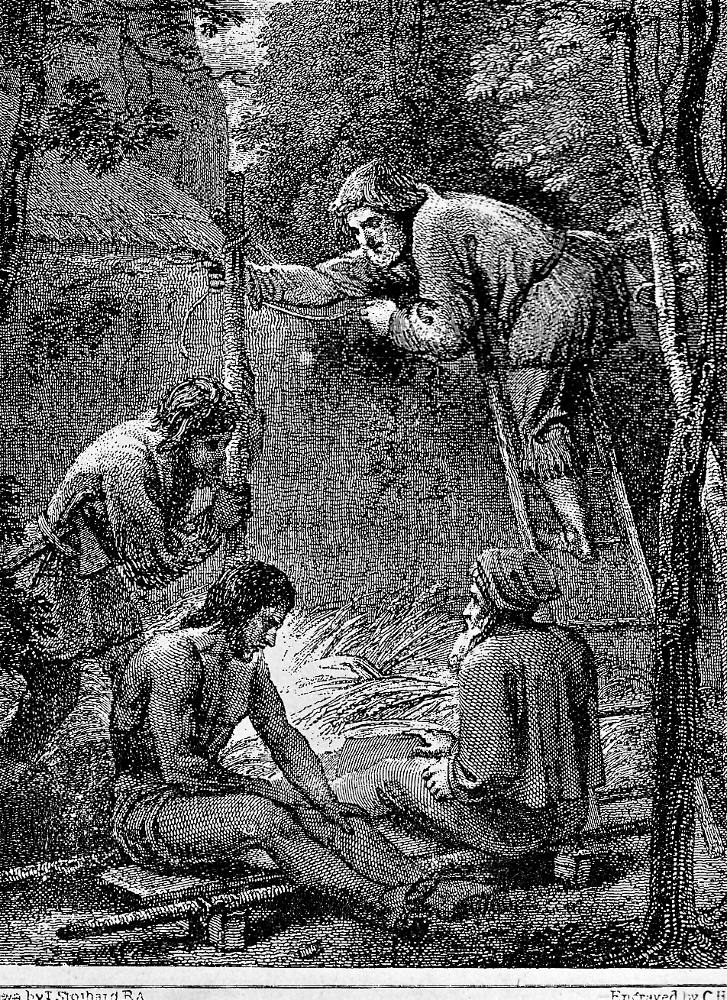

Above: George Cruikshank's suspenseful wood-engraving of Crusoe and Friday's scouting the cannibals' position prior to attempting to rescue Spanish prisoner and dinner-guest, Crusoe and Friday watch the Cannibals from hiding (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Wal Paget's dramatic lithograph of Crusoe and Friday's shooting the enemy from cover prior to rescuing the cannibals' European captive, "I fired again among the amazed wretches."/span> (1891). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Phiz's's dramatic steel-engraving of Crusoe's rescuing the cannibals' European captive, Robinson Crusoe rescues the Spaniard (1864). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Left: The original Stothard copper-plate engraving in which Crusoe welcomes both former captives, the Spaniard and Friday's father (1790), Robinson Crusoe builds a tent for Friday's father and the Spaniard. Centre: Wal Paget's study of Crusoe's approaching the apparently lifeless captive with trepidation: "I made directly towards the poor victim" (1891). Right: John Gilbert's realisation of the rescue scene, de-emphasizing the violence and bloodshed, The Rescue of the Spaniard (1860s). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 18 March 2018