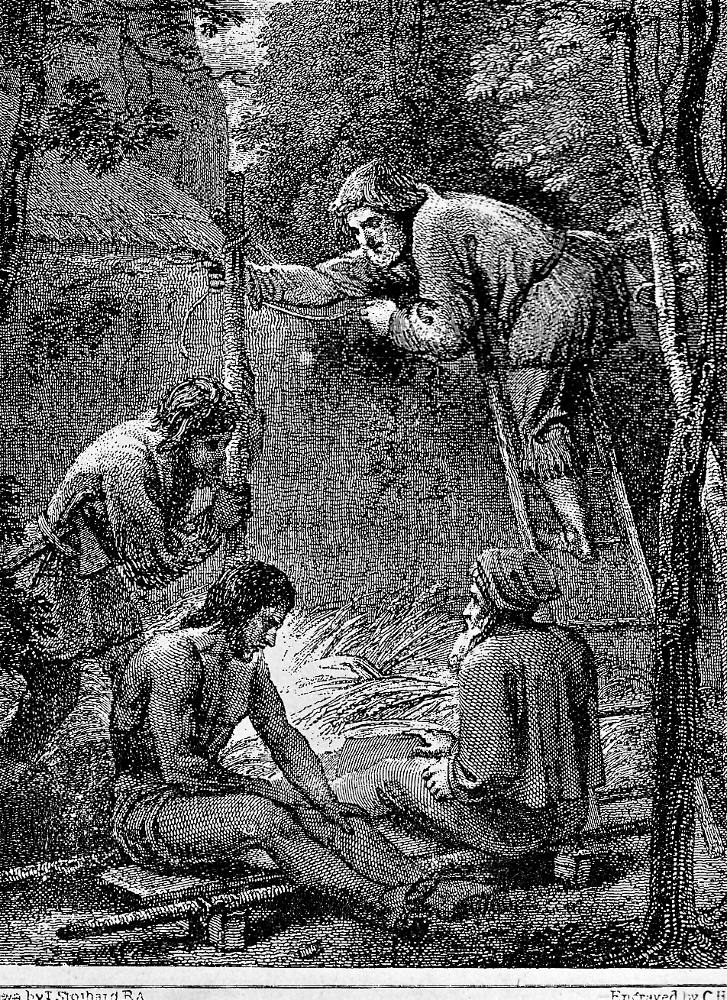

I fired again among the amazed wretches (See p. 168), signed "Wal Paget." The centrally positioned illustration momentarily puzzles the readers, for like the cannibals, viewers wonder about the source of the withering fire that has already felled ten members of the war-party. A thorough examination of the lithograph reveals the two bursts of gunfire in the upper right quadrant, showing how Crusoe and Friday are employing cover near the shore to strike down the cannibals at a distance with bird-shot rather than risking exposing themselves — although Paget does not indicate that the cannibals are armed. One-third of page, vignetted: 9 cm high by 12.1 cm wide. Running head: "A Spaniard Rescued" (page 169).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Crusoe and Friday to the Rescue

Friday took his aim so much better than I, that on the side that he shot he killed two of them, and wounded three more; and on my side I killed one, and wounded two. They were, you may be sure, in a dreadful consternation: and all of them that were not hurt jumped upon their feet, but did not immediately know which way to run, or which way to look, for they knew not from whence their destruction came. Friday kept his eyes close upon me, that, as I had bid him, he might observe what I did; so, as soon as the first shot was made, I threw down the piece, and took up the fowling-piece, and Friday did the like; he saw me cock and present; he did the same again. “Are you ready, Friday?” said I. “Yes,” says he. “Let fly, then,” says I, “in the name of God!” and with that I fired again among the amazed wretches, and so did Friday; and as our pieces were now loaded with what I call swan-shot, or small pistol-bullets, we found only two drop; but so many were wounded that they ran about yelling and screaming like mad creatures, all bloody, and most of them miserably wounded; whereof three more fell quickly after, though not quite dead.[Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the Prisoners from the Cannibals," page 168]

Commentary: Rescuing the Spanish Captive

Paget establishes the precise textual passage realised through a caption that is a direct quotation from page 168, a source he has noted in his caption. Paget implies that the European and his man-servant, though vastly outnumbered, enjoy a considerable advantage in their modern military technology. The cannibals look about, unsure of where and how they are being attacked. The demonstration in this illustration of the superior fire-power of the European colonist may for readers in 1891 have recalled such military engagements as the Battle of Rorke's Drift on 22 January 1879. In this famous engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War, a garrison of roughly 150 British and colonial troops turned back the intense assault of a Zulu army of perhaps four thousand warriors. Paget depicts Crusoe's calculated attack as highly effective, although not particularly heroic. In contrast, the press made much of British heroism in this eleven-hour battle, and the military authorities made Rorke's Drift synonymous with British pluck by awarding no less than eleven Victoria Crosses to the gallant defenders. The 1964 film Zulu, featuring young Michael Caine as an aristocratic officer, remains a television favourite in Great Britain to this day. More Victoria Crosses were awarded to the troops at Rorke's Drift than at any other single British military engagement.

Crusoe originally has no intention to interfere in the cannibals' second grisly feast as long as they leave him alone. However, when Crusoe realizes that one of the victims is bearded, he concludes that he must intervene to preserve the life of a "Christian." However, such intervention may expose him to considerable danger, both in the actual battle to liberate the Spanish captive, in which he and Friday are badly outnumbered, and afterwards, should any of the cannibals escape to return later to take revenge on Crusoe. That same instability of Crusoe's situation in Part One repeats itself in Part Two when one of the captured natives escapes from the plantation of the two "honest" Englishmen and reports to his fellows on the mainland that a small group of Europeans have colonized the island. The result, once again, is an invasion, followed by the Europeans' defeating the aboriginals.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from other nineteenth-century editions, 1790-1860s

Above: George Cruikshank's 1831 realisation of Crusoe and Friday's conducting surveillance before launching an assault on the cannibals, Crusoe and Friday watch the Cannibals from hiding (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Phiz's's dramatic steel-engraving of Crusoe's rescuing the cannibal's European captive, Robinson Crusoe rescues the Spaniard (1864).

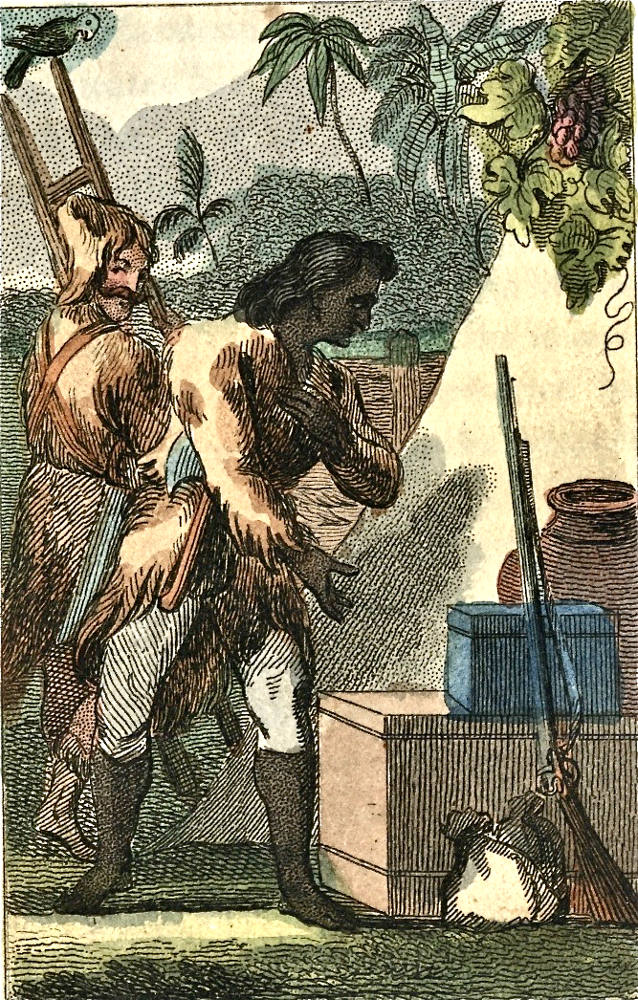

Left: The original Stothard copper-plate engraving in which Crusoe welcomes both former captives, the Spaniard and Friday's father (1790), Robinson Crusoe builds a tent for Friday's father and the Spaniard. Centre: From the 1818 children's book, the far less violent Friday and his Father. Right: John Gilbert's realisation of the rescue scene, de-emphasizing the violence and bloodshed, The Rescue of the Spaniard (1860s).

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 18 March 2018