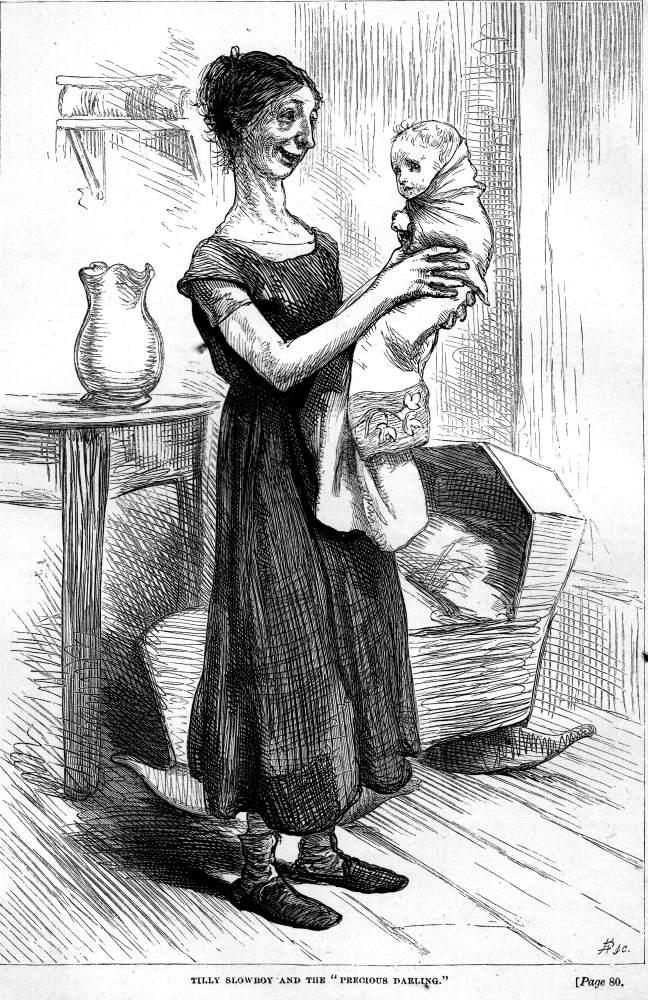

Tilly Slowboy

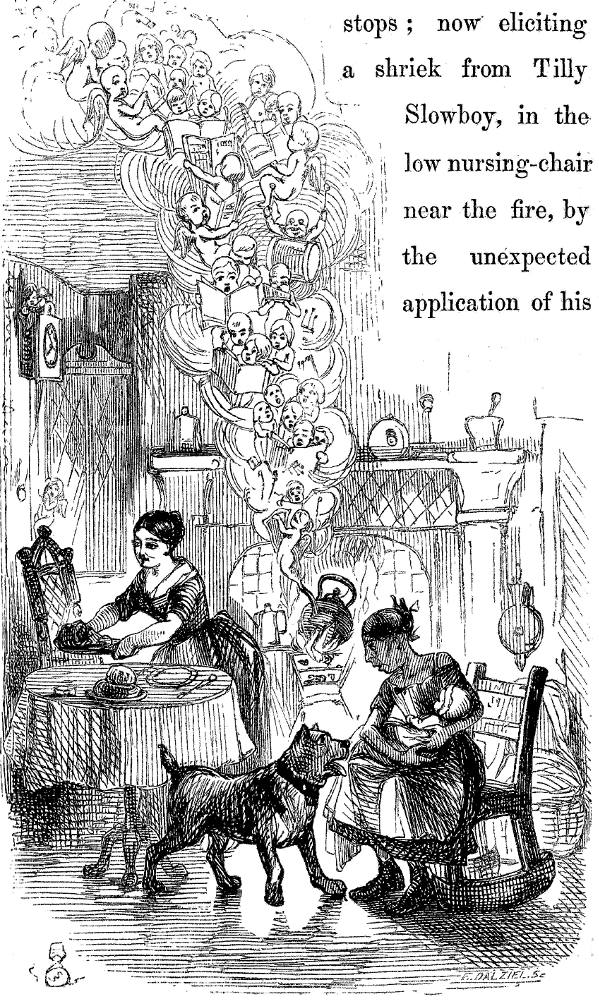

Fred Barnard

1878

Vignetted, 13.8 x 0.5 cm (5 ½ by 4 ¼ inches), vignetted.

Third illustration for Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth, "Chirp the First," 88.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.