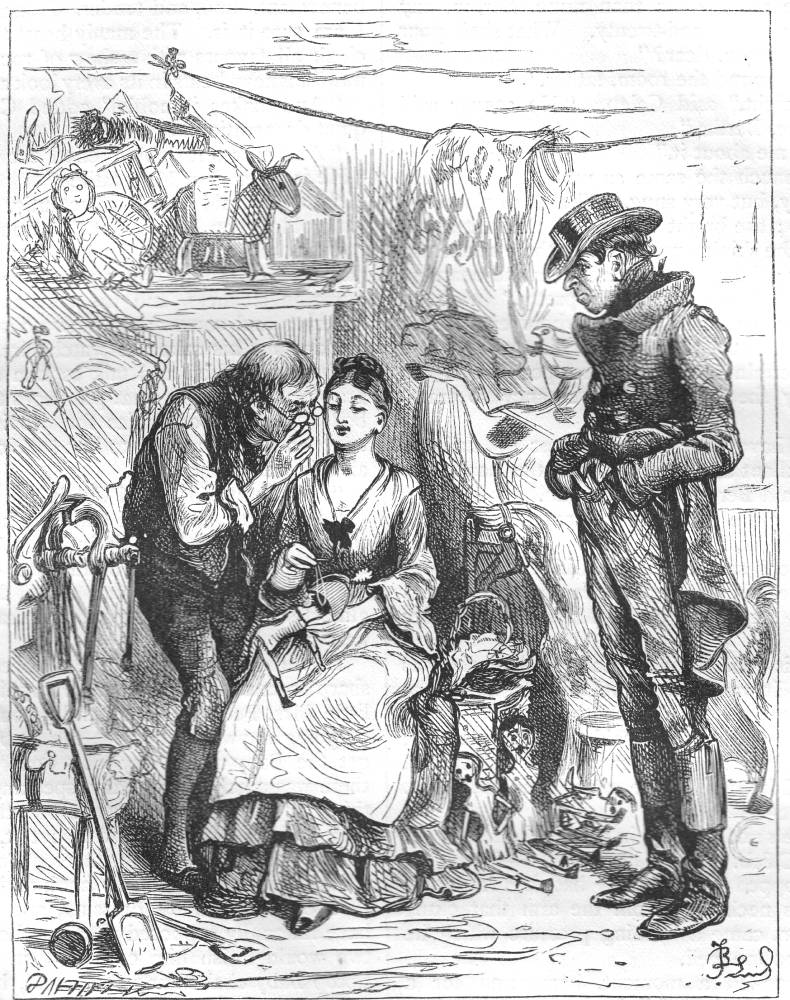

"The extent to which he's winking at this moment!" whispered Caleb to his daughter. 'Oh, my gracious!"

Fred Barnard

1878

13.8 x 10.8 cm (5 ⅜ by 4 ¼ inches), framed.

Third illustration for Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth, "Chirp the First," 93.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham.