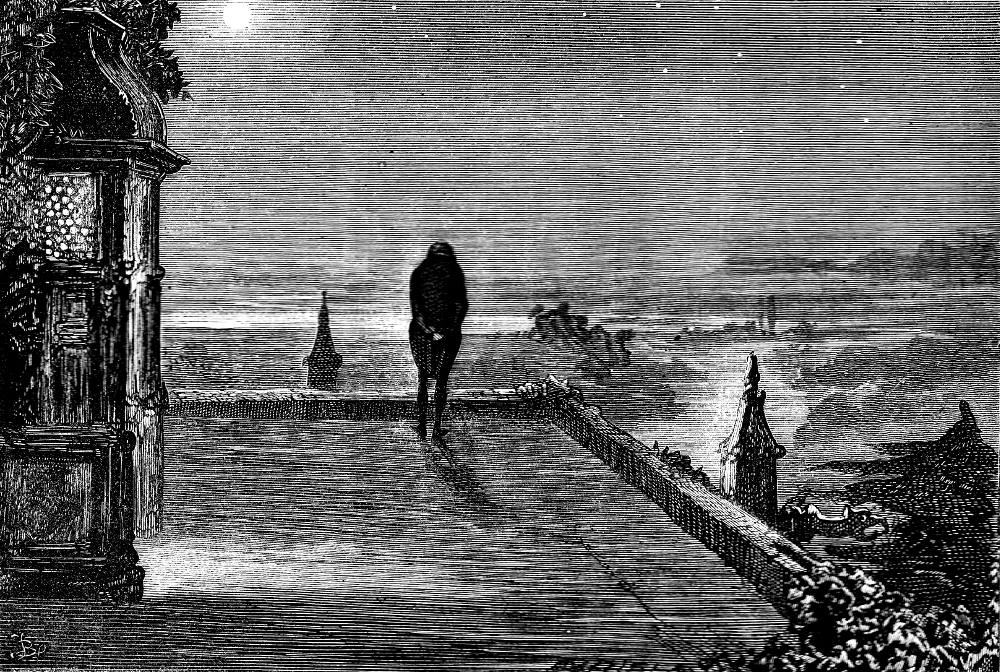

A Bird of Ill Omen — forty-first illustration by Fred Barnard in the Household Edition (1873). 9.4 cm high by 13.6 cm wide (3 ⅝ by 5 ⅜ inches), framed, p. 285. Chapter 41. Running head: "The Ice Breaks" (289). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Text Illustrated: Ruminating on Lady Dedlock's Fate

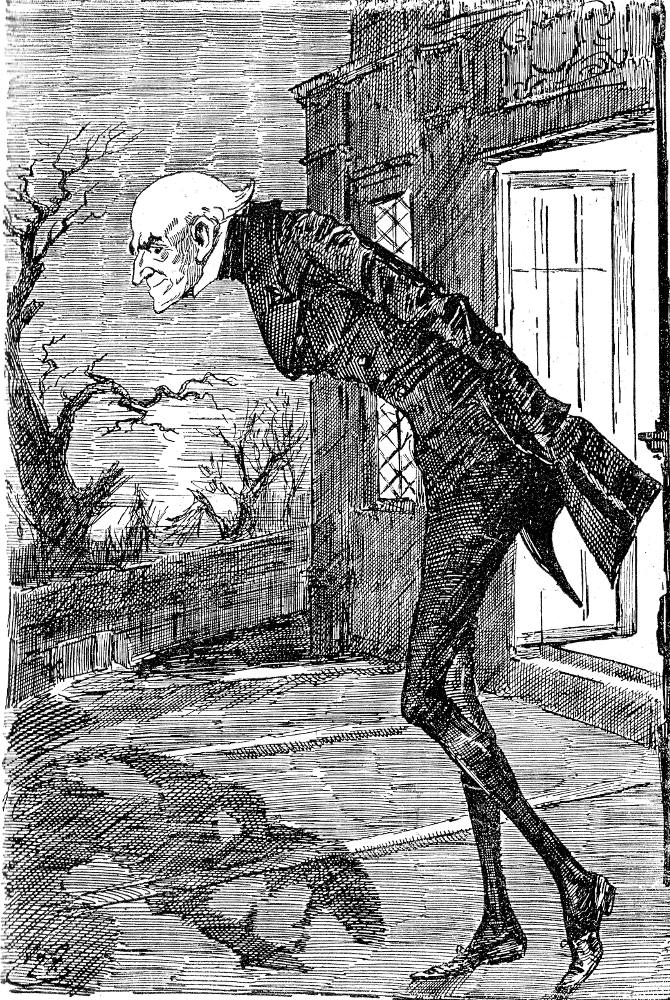

Harry Furniss's portrait of the ruminating attorney on the roof at Chesney Wold: Tulkinghorn on the Leads (1910).

There is a capacious writing-table in the room on which is a pretty large accumulation of papers. The green lamp is lighted, his reading-glasses lie upon the desk, the easy-chair is wheeled up to it, and it would seem as though he had intended to bestow an hour or so upon these claims on his attention before going to bed. But he happens not to be in a business mind. After a glance at the documents awaiting his notice — with his head bent low over the table, the old man's sight for print or writing being defective at night — he opens the French window and steps out upon the leads. There he again walks slowly up and down in the same attitude, subsiding, if a man so cool may have any need to subside, from the story he has related downstairs.

The time was once when men as knowing as Mr. Tulkinghorn would walk on turret-tops in the starlight and look up into the sky to read their fortunes there. Hosts of stars are visible to-night, though their brilliancy is eclipsed by the splendour of the moon. If he be seeking his own star as he methodically turns and turns upon the leads, it should be but a pale one to be so rustily represented below. If he be tracing out his destiny, that may be written in other characters nearer to his hand.

As he paces the leads with his eyes most probably as high above his thoughts as they are high above the earth, he is suddenly stopped in passing the window by two eyes that meet hisown. The ceiling of his room is rather low; and the upper part of the door, which is opposite the window, is of glass. There is an inner baize door, too, but the night being warm he did not close it when he came upstairs. These eyes that meet his own are looking in through the glass from the corridor outside. He knows them well. The blood has not flushed into his face so suddenly and redly for many a long year as when he recognizes Lady Dedlock. [Chapter XLI, "In Mr. Tulkinghorn's Room," 288]

Commentary

Barnard presents the cunning attorney as a diminutive figure in the darkness on the leads of the traditional estate of the Dedlocks, Chesney Wold. Although Dickens presents the starlit scene as reflective of the fates of the aristocratic house and their confidential attorney that now hang in the balance, Barnard uses the night scene to reflect Tulkinghorn's indecision about the ignominious fate hanging over Honoria Dedlock, and by extension her aristocratic husband, Sir Leicester. Tulkinghorn remains determined to protect the family name, the Chesney Wold establishement, and Sir Leicester's happiness. He therefore arrives at the decision not to expose Lady Dedlock's past in order to preserve the marriage. After pacing about on the leasds, he encounters Lady Dedlock herself in his room, and announces his decision. She had hoped simply to disappear, but the lawyer vetoes that course of action.

Other Illustrations of The Deadlocks and Their Lawyer, 1852-1910

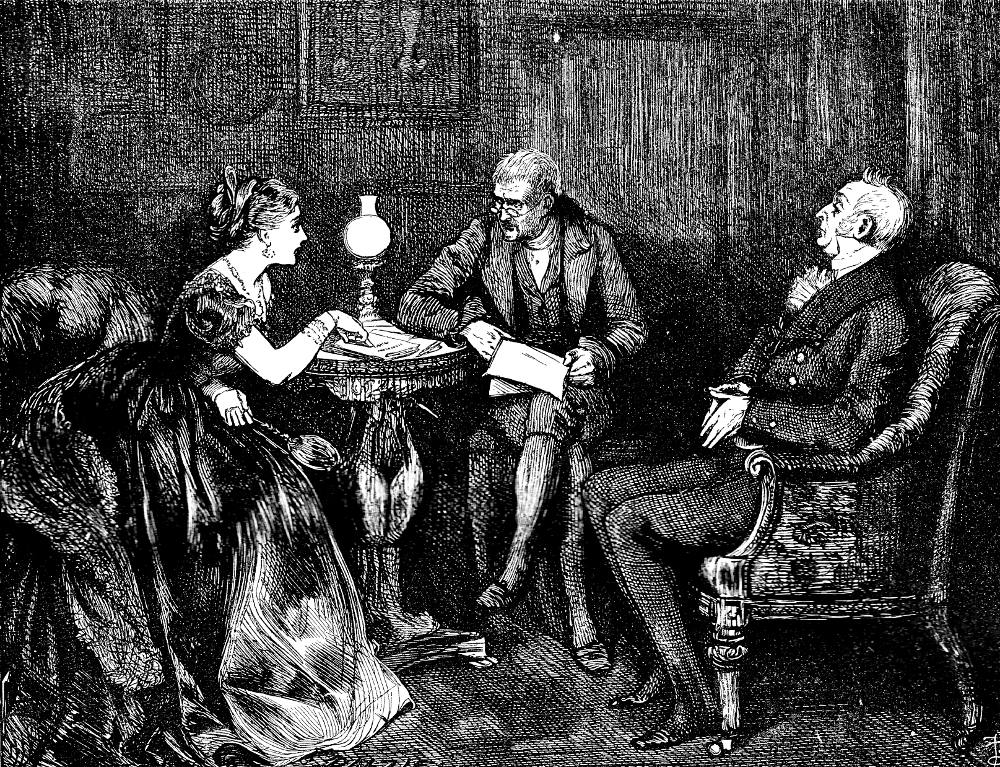

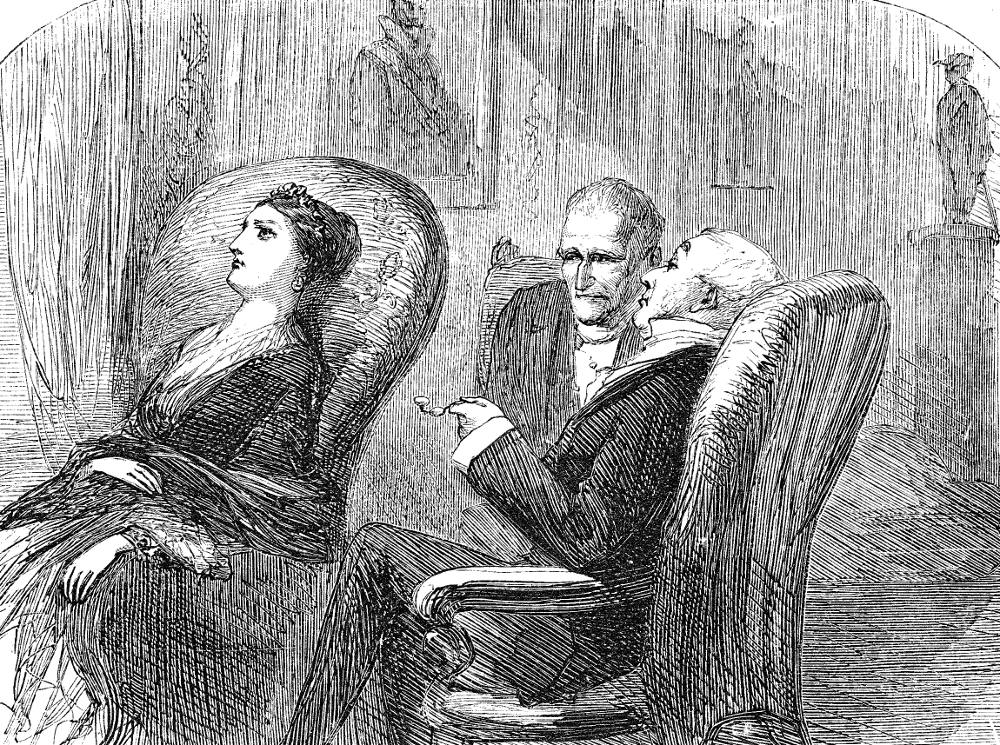

Left: The original Phiz introduction of the lawyer, The old man of the name of Tulkinghorn (January 1853). Centre: Fred Barnard's 1873 Household Edition illustration of the trio: "Who copied that?" (headpiece for Chapter One). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 's Diamond Edition full-page wood-engraving of the secretive attorney and his chief clients: Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock and Mr. Tulkinghorn (1867).

Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions of Bleak House

- Bleak House (homepage)

- Phiz's Illustrations for Bleak House (March 1852 - September 1853)

- Sir John Gilbert's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 4, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Harry Furniss's Illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's five Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

"Bleak House — Sixty-one Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Collins, Philip. Dickens and Crime. London: Macmillan, 1964.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vols. 1-4.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr, and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. VI.

_______. Bleak House, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. IV.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [28 original lithographs]. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Vol. 11. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_______. Bleak House, ed. Norman Page. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 18: Bleak House." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. XVII, 366-97.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70.

Created 18 March 2021