uring the nineteenth century the flower spray brooch- which had been so popular in the eighteenth century underwent considerable changes in design and technique. Prince Albert's design for the. set of orange-blossom jewellery is in the minutely naturalistic style which was characteristic of the Romantic jewellery made in the form of flowers and branches entwined with leaves, which had become fashionable in the early years of the century and which was developed by French jewellers like Oscar Massim and Octave Loeulliard and the Russian, Carl Fabergé. The 'Moss Rose' brooch designed by Massim in 1863, which was so popular that the design was repeated for over twenty years, seems to have been conceived under the influence of contemporary English design. Plate 113 shows an English diamond brooch in the form of a rose spray made in the same year.

Massim had just spent eighteen months in London studying English jewellery techniques which were much admired by the French. English workmanship of this period is described by Vever in La Bijouterie Francaise au XIXs Siecle as 'tres soignée', which is ironical in the circumstances, since the English regarded French technique and design as greatly superior to their own. The 'Moss' Rose' design was produced not long after his return to France. Massim was already a considerable figure in the world of fashionable jewellers in Paris before this visit to England; it was he who had designed and made the diadem, set with the famous 'Regent' diamond, which the Empress Eugenie wore at the opening of the Exposition Universelle in 1855, but it was only after his return from London that he began to make the famous flower sprays which became his speciality, the sprays with springmounted and mobile parts, decorated with diamonds set 'en pampilles', which he produced almost without alteration until the [216/217] eighties. The characteristic precision of design and brilliance of finish, which is typical of French botanical jewellery from the sixties onwards, distinguishes it from the flower sprays and bouquets tremblants of the eighteenth century. The Massim style was elaborated to a point at which designs, made by Loeulliard for Boucheron, were critisized for striving after the exact representation of natural forms at the expense of the actual function of the jewel which is to enhance the appearance of the wearer, a critisism which could equally well have been levelled at Carl Fabergé and the Art Nouveau jewellers who clearly tended to regard a piece of jewellery as a work of art rather than as a fashionable accessory.

Loeulliard's designs for Boucheron which date from the seventies and eighties anticipate the interest in unusual plants which is so noticeable in the work of the Art Nouveau designers, his delicate ferns and single blooms compare strangely with the massive bouquets which were fashionable twenty years earlier and still favoured by the more conventional designers of the time, the type of jewellery which featured prominently in the various international exhibitions of the nineteenth century. In 1851 Hunt and Roskell's piece de résistance was a

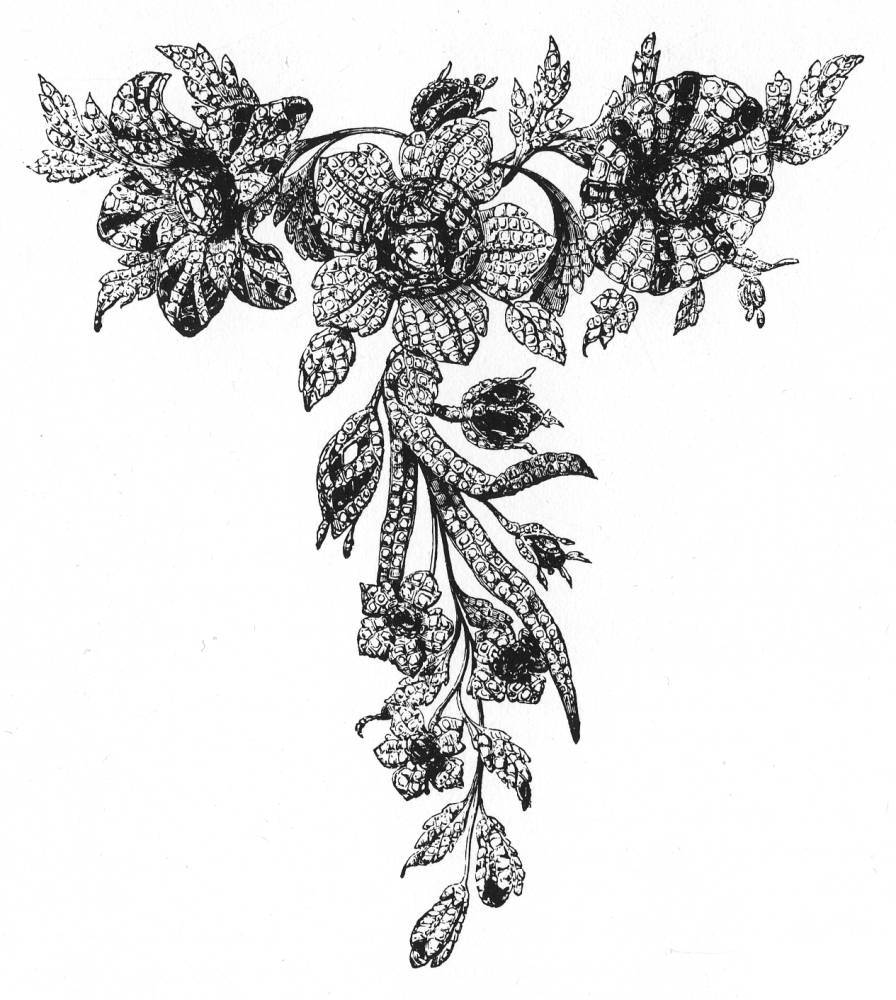

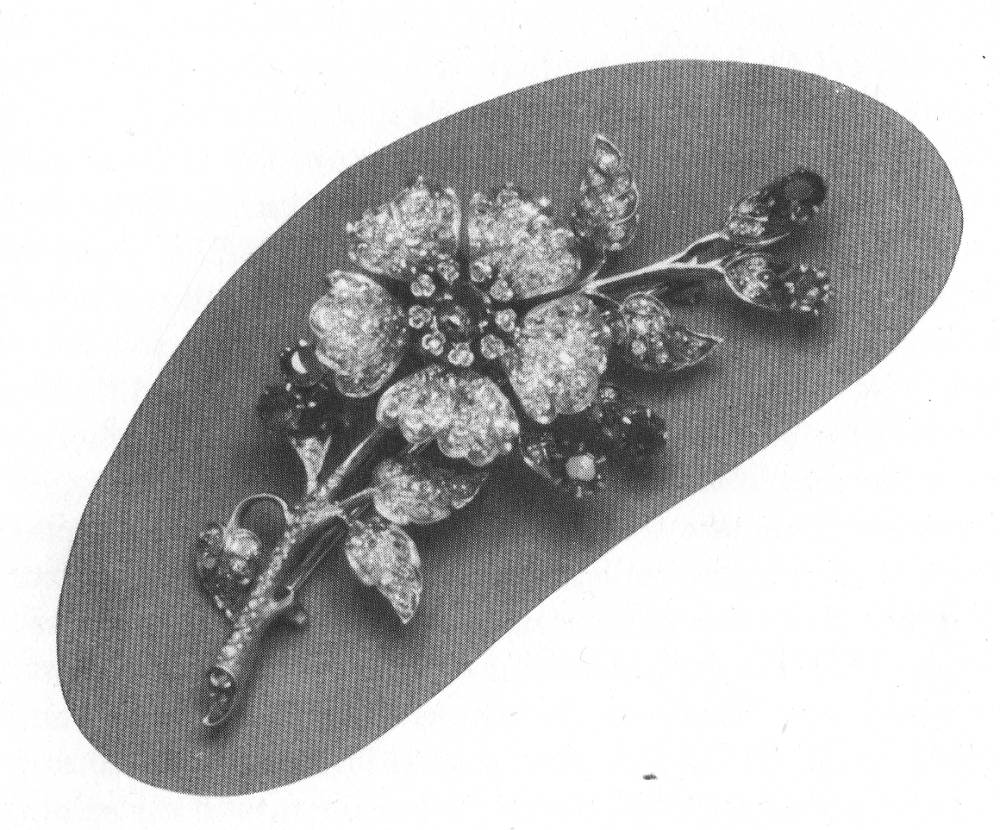

Diamond bouquet, being a specimen of the art of diamond setting. The flowers: the anemone, rose carnation, &c., are modelled from nature. This ornament divides into seven different sprigs, each complete in design, and the complicated flowers, by mechanical contrivances, separate for the purpose of effectual cleaning. It contains nearly 6,000 diamonds, the largest of which weighs upwards of 10 carats, and some of the smallest in the stamens of the flowers would not exceed 1,000th part of a carat.

The Empress Eugenie bought a diamond lilac spray by Rouvenat, which had been copied from a blossom which lay on the workbench beside the jeweller as he worked, from the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867.

This fashion for botanical jewellery is a development of the widespread interest in botany and horticulture in the early nineteenth century, an interest which is understandable in view of the activity in the horticultural world. Many of the commonplace garden plants which now furnish every garden with hardy decorative flowers are not natives of this country and have only been generally available for little more than one hundred and fifty years. The idea of the flower garden as a place where plants might [217/218] be cultivated purely for their dec x ative qualities as distinct from their medicinal or nutritive value as a comparatively recent one, and its wide adoption during the eighteenth century stimulated public interest in flowering garden plants. Towards the end of the eighteenth century and in the first half of the nineteenth century plant-collecting became a positive mania amongst the well-to-do gardeners of this country, some of whom, like the sixth Duke of Devonshire, mounted their own expeditions to the East to search for new species. Even though it could be an excessively expensive hobby, plant-collecting was not confined to the rich land-owners; northern weavers, earning no more than a few shillings a week were prepared to give two or three pounds for a rare species of carnation or Laced Pink. Loudon, in his Encyclopaedia of Gardening, published in 1828, draws a comparison between the skill in raising delicate flowers and producing the complex designs for muslins: ' . . . their attention to raising flowers contributed to improve their genius for invention in elegant fancy muslins', the passionate interest in botany which characterises the first half of the century accounts for the excellence of the early nineteenth century botanical illustrations and the delicate decorative work which they inspired.

The first half of the nineteenth century saw the introduction to this country of a number of species of plant which could not have been grown here before the development of the hot-house, hardy strains of many of these exotics which came mainly from Turkey, India and China, were developed later. Expeditions to the East and to North and South America produced a large number of new plants of which many became the inspiration for Victorian decorative artists. Among these were the Tiger Lily (brought back from Canton in 1804), the Petunia (1831), Penstemon (1827), Potentilla (1822), Wisteria sinensis (sent to the Horticultural Society from' China in 1817), Primula denticulata (sent by the Directors of the East India Company in 1837), rhododendrons, azaleas, hydrangeas, the magnolia and the gardenia, species of roses (from China) and chrysanthemums.

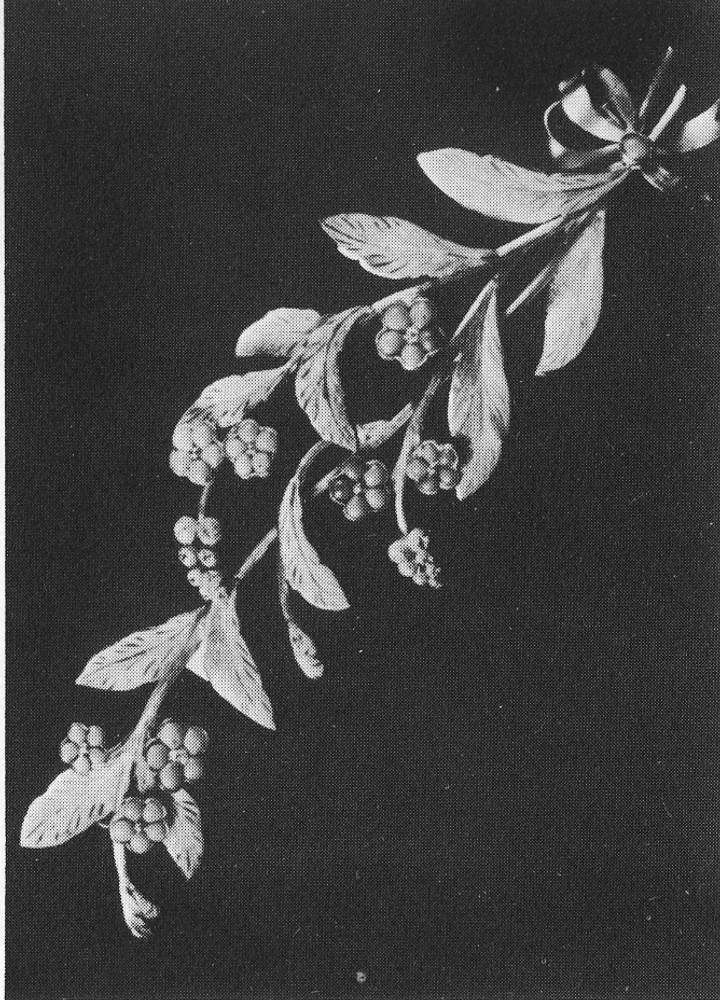

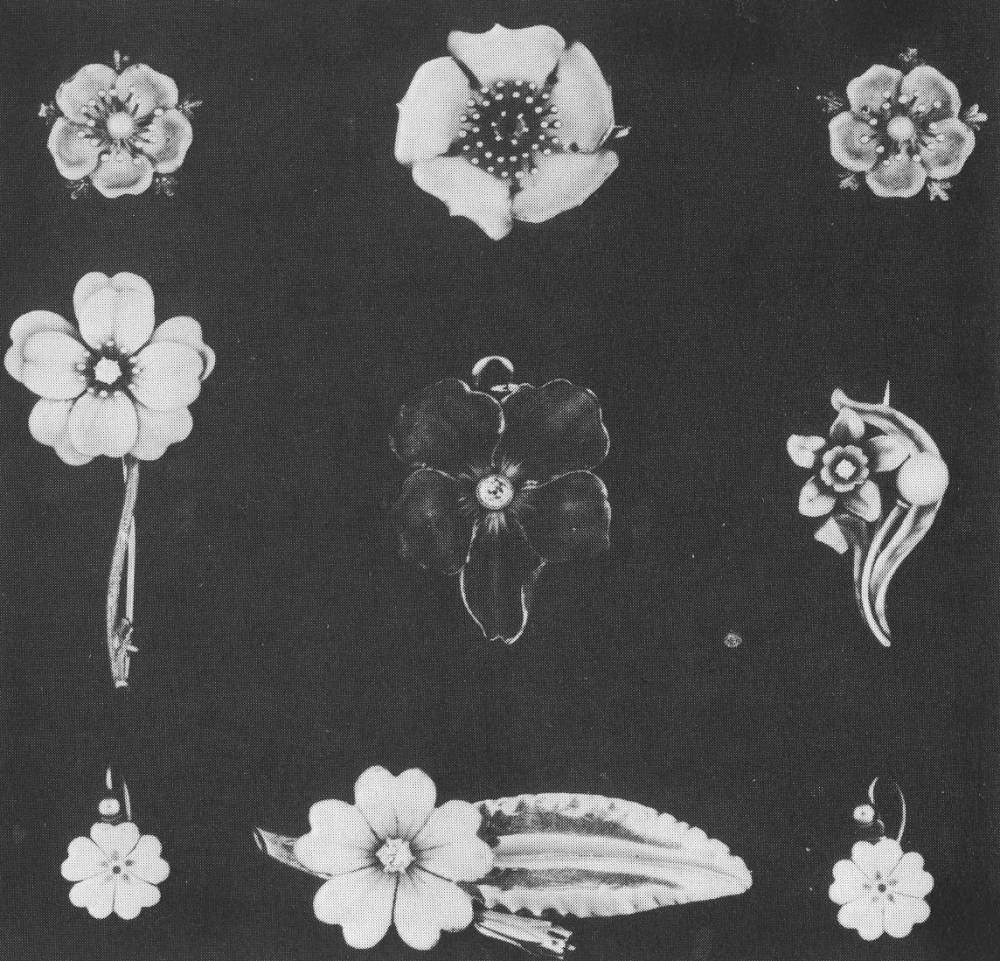

Flower Spray Jewellery 1820-45. Plate 109a. brooch in the form of a wild rose, gold with white coral shading to pink(left) . Plate 109b. brooch in the shape of a spray of forget-me-not, gold and turquoises. This delicate flower jewellery of the early part of the century was superseded by the heavier bouquets of the fifties and sixties. Courtesy of Cameo Corner.

Plate 109c. Brooch in the form of a small bouquet, gold with ivory and turquoises. Courtesy of Cameo Corner.

In 1807 the Empress Josephine, whose garden at Malmaison provided one of the focal points of botanical interest in Europe, had a garland of hydrangeas included in a diamond parure. H. Hortensia or macrophylla, which was called Hortensia after Mlle. [218/219] Hortense Nassau, daughter of the rnnce ot Nassau, was established in France towards the end of the eighteenth century. In 1789 a plant from China was introduced by Sir Joseph Banks to Kew. The Dahlia, a native of Mexico, was introduced into Europe at the end of the eighteenth century, and many varieties were grown by the Empress Josephine at Malmaison, like the famous roses and Parma violets. French varieties of the Dahlia became available here after 1815, and by 1830 it had become one of the most fashionable flowers in the country. The Dicentra, D. spectabile or Bleeding Heart was introduced in 1846 from China by Robert Fortune and appears on many wallpapers and furnishing fabrics in the [219/220] seventies.

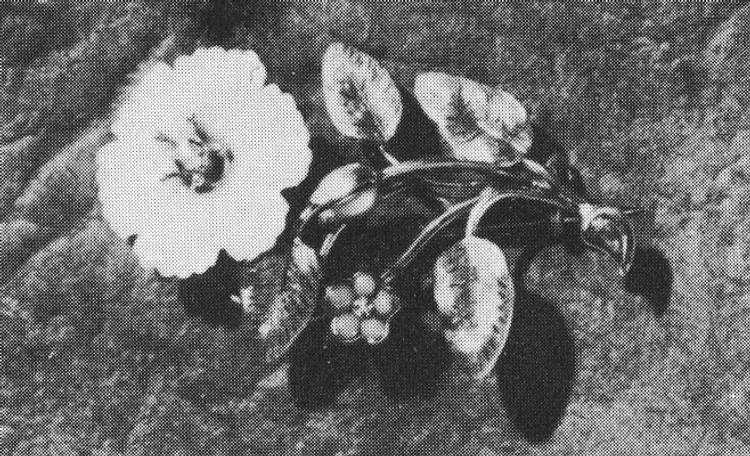

Left. Plate 110. Fuchsia brooch in diamonds and translucent enamel by Georges Fouquet c. 1900. Courtesy of Hessiches Landes-museum, Darmstadt. The pre-occupation of the Art Nouveau designers vith natural form led to a number of jewels being made in the shape of flowers, ferns and fruit. They are among the most wearable pieces made in this style. Right: Plate 111. Fuchsia brooch, diamond. French 1848-50. Both the fuchsia and the 'waterfall' or 'pampilles' setting became popular in France at this date. Courtesy N. Bloom and Son.

The modern variety of the pansy was not developed until the early nineteenth century when experiments in the cultivation of the native viola produced the large flower that we know today. The first blotched variety was grown in 1830, and the richly coloured velvety variety, which closely resembles the modern flower, was raised in 1861. These flowers aroused great interest and this type of pansy is found in jewellery design from very soon after the first large varieties became generally available, c.1840. The larger form of the Iris was also developed at this time, the later varieties with their wide range of colour and large size [219/220] which are one of the most extensively exploited features of Art Nouveau botanical jewellery being introduced by the French firm, Vilmorin, in the 'eighties. Other flowers, although native to this country or earlier introductions, have taken on a specifically Victorian character owing to their popularity during that period; ignored at the time of their first appearance they were taken up by Victorian gardeners, like geraniums, fuchsias and sweet-peas, or holly which was fashionable in the 'Italian' gardens of the 'sixties and is occasionally found in jewellery of the period. Although it is not impossible that one of these neglected plants should find its way into earlier designs it is quite unlikely and it is usually safe to assume that the geranium or fuchsia is a Victorian motif in the same way that the sweet-pea, whose seeds had been available since the early eighteenth century, is peculiar to Edwardian decoration.

Plate 112. Jewelled flower spray shown at the Great Exhibition in 1851 by J. V. Morel, the French jeweller who came to England in 1848 and established his business at 7, New Burlington Street. Illustrated London News, July 26th 1851.

A drawing of the fuchsia was first published as far back as 1703, but it fell into complete obscurity and was only rediscovered in the closing years of the century. The single variety became popular as a bedding plant, but the next thirty years saw the introduction of a large number of new varieties and intensive hybridisation produced the more spectacular plant which we know today. The diamond trembler brooch in the form of a spray of fuchsia on pi. Ill was probably made after 1830, the time when the fuchsia became fashionable; brooches like this were made in France c. 1840-50. The 'water fall' or 'pampille' setting (stones set on articulated wires) which decorates this brooch was developed in France in the forties, and is found on a number of similar flower-spray brooches of the period, becoming the height of fashion in about 1850-58. Lemmonier's jewels made for the Queen of Spain which were shown in the Great Exhibition in 1851 were decorated in this way; they closely resembled the brooch worn by the Empress Eugenie in the portrait on plate 33. In the absence of marks or a style of cutting or setting which date them, many of these trembler brooches in the form of flower sprays are inevitably called 'Georgian', a rather unsatisfactory term covering a period of more than a hundred years, since neither the term 'Regency' nor 'William IV is used in connection with jewellery, and 'Romantic' only rarely, and then more to describe the style than to fix the date. It is reasonable to argue that the preoccupation with accurate dating is irrelevant with jewellery of this quality, but [221/222] there is a particular snobbism attaching to the term 'Georgian' which tends to affect the price of those pieces to which it is attached.

Other flowers which were no longer novelties became identified with particular artistic movements as Oscar Wilde pointed out in a lecture given in New York L 1882 (The English Renaissance of Art):

You have heard, I think, a few of you, of two flowers connected with the aesthetic movement in England, and said (I assure you, erroneously) to be the food of some aesthetic [222/223] young men. Well, let me tell you that the reason we love the lily and the sunflower, in spite of what Mr Gilbert may tell you, is not for any vegetable fashion at all. It is because these two lovely flowers are in England the most perfect models of design adapted for decorative art — the gaudy leonine beauty of the one and the precious loveliness of the other giving to the artist the most entire and perfect joy.

The mediaeval mania had made the Madonna Lily fashionable some years before and the Japanese influence on the decorative arts which was a characteristic of Aesthetic taste had popularised the sunflower, and the chrysanthemum, though Wilde does not mention this. The chrysanthemum, like the fuchsia and the dahlia, was a late eighteenth century introduction, and like them had failed to attain great popularity at the time. It was the discovery of the Japanese variety at a particularly opportune moment (it was brought back from Japan in 1861 by Robert Fortune) which ended its period of obscurity and this flower, like the Iris, was developed in a wide range of colours — luckily of the sort favoured by Aesthetic taste — by the firm of Vilmorin.

Plate 113. Diamond flower spray 'trembler.' English marked 1863. This brooch with the/lowers mounted on springs to make them tremble with every movement, was made in the same year as Massim's famous 'moss rose' spray. Courtesy Howard Vaughan.

Left: Plate 114. Enamel flowers, brooches, earrings and a pendant. This flower jewellery, like the enamelled and jewelled insects and butterflies, was very fashionable in the eighties. Courtesy Cameo Corner. Right: Plate 115. Gold and pearl spray brooch by Vever c. 1900. This type of Art Nouveau design was widely copied in England. Courtesy of Hessiches Landes-museum, Darmstadt.

Botanical magazines of the Victorian period, like fashion periodicals, were numerous and lavishly illustrated, as were the less [223/224] ephemeral dictionaries and encyclopaedias of plant; which were published at this time and it is possible to trace the influence of a common taste on both the botanical illustrators and the jewellers of the time. The early flower drawings are more delicate than the massive set-pieces of the mid-century, a development which is reflected with some accuracy by the jewellery design of the same period. The rose spray brooch on plate 109 which dates from c. 1825-30 is like the drawings in Redoute's famous work Les Roses which appeared 1817-29. These early nineteenth-century pieces are a contrast to the later large bouquets of diamonds or coloured stones and enamels which were the pieces de resistance of jewellers who wished to make an impact at an exhibition. The delicacy of touch and more appropriate use of materials of the early designers was to a large extent regained at the turn of the [224/225] century by the jewellers of the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau, by Lalique and Eugene Grasset, or the more obscure English designer, Arthur Gaskin, though exceptions in the mid- nineteenth century like the two French designers, Massim and Loeulliard whose fern and flower designs anticipate the assymetry of Art Nouveau and the simplicity of the twentieth century. The popularity of ferns in late nineteenth century decoration was due to the development of the 'Wardian case', a glass box designed for the cultivation of non-hardy ferns, by Dr N.B. Ward, for which Victorian ladies developed an almost maniac enthusiasm. Dr Ward published On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases, in 1842 and exhibited a large case filled with ferns in 1851. [225/226]

The pattern books of decorative designs produced during the nineteenth century, which must have been the source of many of the jewellery designs of the period, especially of those pieces from the less-inspired or extensively mechanised firms, dealt at length with the ways in which natural forms could be rationalised and adapted for use in the decorative arts. Ruskin, Richard Redgrave, Owen Jones, and Pugin, among others, stress the necessity for using natural forms as a basis for the shape and design of decorative objects or their ornamentation. The Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones, published in 1856 shows the way in which plant forms were to be adapted for decoration, and this same theme is pursued by Christopher Dresser, who was in fact a Doctor of Botany, in his articles on The Principles of Design which appeared in the Technical Educator in 1871 and 1872, where the patterns are strongly influenced by the currently fashionable Japanese forms. Dresser specifically mentions 'works in silver and gold, jewellery' and says that the papers are addressed to 'silversmith' and 'jeweller', among others. Ruskin's Proserpina, which appeared from 1874-1886, with its evocative descriptions of plants and their habit of growth, sums up all he had tried to convey about the use of natural ornament in decoration, and it is the influence of his teaching in this matter on the imagination of Millais which provided the designs which form the most interesting link between the naturalistic jewellery design of the 1850s and the eclectic use of organic forms in the jewellery of the 1900s.

La Plante et ses Applications Ornamentales, edited by Eugene Grasset (English edition by Chapman and Hall) which appeared in monthly parts from 1896 to 1900 and Alphonse Mucha's Documents Decoratifs (1902) go further than the Grammar of Ornament in providing completed designs for metalwork adapted from the flowers that are illustrated, Mucha's book actually including several pages of designs for jewellery in the Art Nouveau style, which Mucha found had been copied in America even before he first went there in 1904.

A.W.N. Pugin, whose influence played a considerable part in spreading the popularity of the Gothic style into every branch of architecture and decoration, had already undertaken, almost sixty years earlier, the considerable task of producing a pattern book of Gothic ornament based on natural forms, called Floriated Ornament, [226/227] which appeared in 1849. The book, which contains thirty-one designs, sets out to prove the desirability o. deriving Gothic ornament directly from nature and the illustrations are based on the plates in an early botanical work owned by Pugin, the Eicones Plantarum, by Jacobus Theodorus Tabernaemontanus, published in Frankfurt in 1590, from which he had been able to identify many of the plants used in Gothic architectural ornament. The influence on the decorative art of the second half of the nineteenth century, and eventually on the Art Nouveau designers, of early herbals such as this book owned by Pugin and Fuchs' De Historia Stirpium (1542), copies of which were owned by both John Ruskin and William Morris, was enormously important. Much of the decorative detail in the Gothic or quasi-Mediaeval style is based on flower and foliage forms, and through Morris, was to influence the fin de siècle designers and even the jewellery of the present day. (Below: Diamond flower spray.)

8 March 2015